Below we are publishing the fourth part of the opening report given by Nick Beams to an international school held by the International Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI) and the International Students for Social Equality (ISSE) in Sydney, Australia from January 21 to January 25. Beams is a member of the international editorial board of the World Socialist Web Site and the national secretary of the Socialist Equality Party of Australia.

Parts one, two and three were posted January 31, February 1 and February 2. The fifth and concluding part will be posted on February 5.

The decade of the 1980s saw the unleashing of capital’s response to the fall in the rate of profit in the previous decade and the severe economic problems to which this gave rise. First and foremost, it launched an offensive against the social position of the working class, which continues to this day, and sought to gouge out additional profit and revenues from the former colonial countries, a process that likewise continues. Combined with these measures came a restructuring of industry through the use of computers and other information technology both in industrial processes and management.

Computers had first been developed in the immediate post-war period and the transistor had been developed in the 1950s, but the personal computer did not make an appearance until 1981. Its use has brought about a vast transformation in a whole series of management and work practices, in communications and in all areas of social life.

However, these changes, while they contributed to an upward shift in the rate of profit in the 1980s, did not result in a new upswing in the curve of capitalist development. This can be seen from an examination of the following two graphs.

(“Long Waves and Historical Trends of Capitalist Development,” Minqi Li, et al)

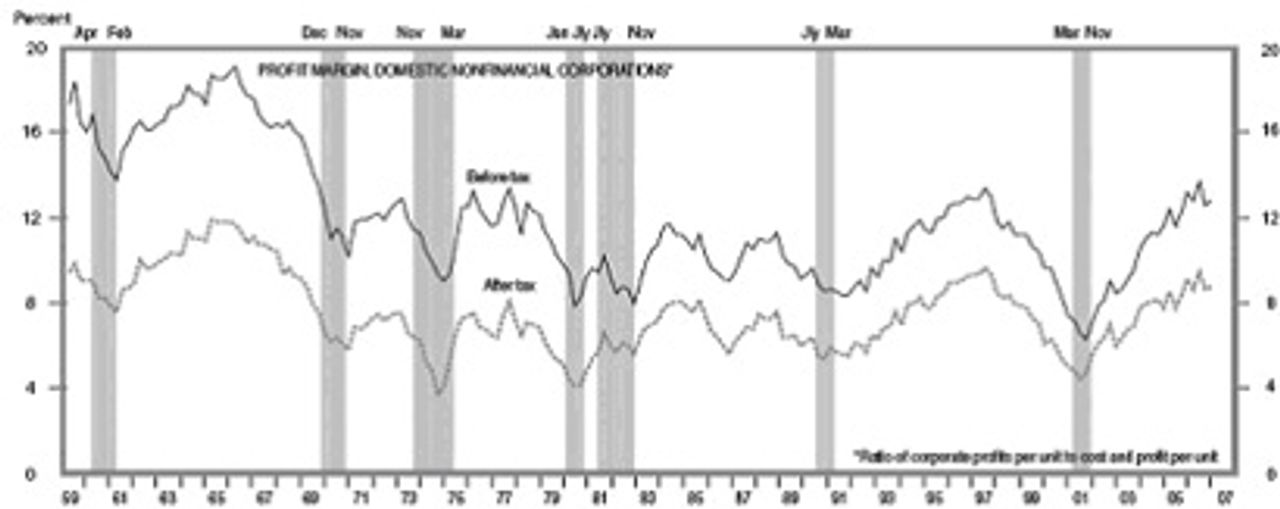

(Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis)

If we look at the second graph, which concerns the US profit rate, we find that while there is a recovery in the 1980s it is not particularly strong, with a quite marked decline in the middle of the decade before a limited recovery, and then another decline at the end of the decade, coinciding with the onset of the 1991-1992 recession.

From the beginning of the 1990s there is a sustained recovery, then a sharp fall from around 1997 to 2001. These years were the period of the stock market bubble. The reasons for the stock market collapse of 2000-2001 are very clear: while stock prices were surging to new highs, the revenue stream to which shares are titles (profits) were turning down—a fact which companies such as Enron and WorldCom sought to obscure with fraudulent accounting procedures.

What is to account for the turn in 1991 and the beginning of a new upswing in the curve of capitalist development? Undoubtedly it is one of the most far-reaching structural changes in the history of world capitalism—the collapse of the Stalinist regimes, the opening up of China, and the ending of the policies of national economic development pursued by countries such as India. In his article “The Curve of Capitalist Development” Trotsky had explained that an upswing was not a product of processes inherent within the capitalist economy itself, but the result of changes in the external conditions within which capitalism develops, such as the acquisition of “new countries and continents.” This is exactly what took place.

Many years before, Trotsky had pointed to the conditions which might make a new capitalist upswing possible.

“Theoretically, to be sure, even a new chapter of a general capitalist progress in the most powerful, ruling, and leading countries is not excluded. But for this, capitalism would first have to overcome enormous barriers of a class as well as of an interstate character. It would have to strangle the proletarian revolution for a long time; it would have to enslave China completely, overthrow the Soviet republic, and so forth” (Trotsky, The Third International After Lenin, New Park Publications, 1974, pp. 61-62).

Trotsky had envisaged that the acquisition of China and the Soviet Union would take place by military means. History took a different course.

While the collapse of the Soviet Union was rooted in economic processes, the restoration of capitalism was not realised “automatically” or inevitably. The Stalinist bureaucracy was fearful that the growing economic inefficiencies of the Soviet economy in the new era of technological development made possible by computerisation, and the Soviet economy’s inability to develop productivity—a result, in the final analysis, of its enforced isolation from the international division of labour—would bring an upsurge of the working class which would call into question its rule. The developments in Poland in 1980-81 were a warning sign.

Faced with this prospect, the Stalinist apparatus decided on a pre-emptive strike—the liquidation of the Soviet Union so as to consolidate its privileges and social position within the framework of capitalist property forms. The fact that it was able to succeed was, as we emphasised at the time, an expression of the crisis of perspective in the Soviet and international working class—a result of the enormous damage done to the political consciousness of the working class by both the political genocide of Marxism in the Soviet Union and the deadly impact of decades of bureaucratic domination of the working class in the major capitalist countries. Had there been a political resistance to the liquidation of the Soviet Union, a very different course of development would have followed. In other words, while the crisis of the USSR was rooted in economic processes, its liquidation and “the acquisition by capitalism of new countries and continents” was the outcome of superstructural factors.

In China, the Maoist bureaucracy has pursued a market-oriented policy since 1978, the basis for which had been laid in the rapprochement with the US in 1971. While this policy had provided a certain economic stimulus, it was producing a series of social contradictions which erupted in the events of 1989 and the Tiananmen Square massacre. The chief target of the regime was not the students, but the working class.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 faced the Chinese regime with a new series of problems. In January 1992, just eight weeks after the liquidation of the USSR, Deng undertook his “southern tour,” signaling the opening up of the Chinese economy to foreign investment and the adoption of a series of “market reforms” internally.

In 1992, more than 8,500 new investment zones were created. Prior to Deng’s tour there had been only one hundred.

Following the lifting of restrictive terms, the inflow of foreign investment nearly tripled in 1992 to $11 billion. It tripled again to $34 billion in 1994 and a decade later, in 2004, had nearly doubled to $61 billion per year. By the end of 2005, some 50,000 US firms were doing business of some sort in China. Since 1978, the Chinese economy has grown by around 9 percent per year—closer to 10 percent, and sometimes more, over the past 15 years.

China has emerged as the chief manufacturing centre of the global capitalist economy. China’s share of world gross domestic product (GDP) has almost tripled in the last quarter century as a result of rapid capital accumulation, rising from 5 percent to 14 percent (Andrew Glyn, Capitalism Unleashed, Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 90).

There has been a ten-fold increase in Chinese manufacturing exports as a share of world manufacturing exports over the past 25 years. Since 1990, the growth of Chinese exports has exceeded in absolute terms the nine next largest low-wage manufacturing exporters put together. Up to one third of Chinese manufacturers are produced from foreign-owned plants, most of these Japanese, which sustains a flow of machinery and components imports into China from Japan (Glyn, pp. 90-91).

Ten years on, one of the crucial consequences of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 emerges more clearly. With the exception of South Korea, the Asian Tigers, after suffering a loss of output of as much as 10 percent, are now growing at a rate 2 percent below that attained in the years prior to 1997. Prior to the crisis, the Tigers had functioned as low-cost manufacturers for the US and European markets. After the crisis, a different structure has emerged. China has become the pre-eminent low-cost manufacturer, drawing in imports of components and intermediate goods from the Southeast Asian region.

The previous structure was sometimes referred to as the flying geese model—the Asian low-cost producers stretched out in formation behind Japan. The structure today is very different. China forms the centre of a giant manufacturing hub.

There are many aspects of the Asian crisis, but at least one of the major causes was the emergence of China as a low-cost manufacturer, able to undercut the Asian Tigers, which had enjoyed increased growth from the middle of the 1980s to the mid-1990s.

The massive investment in China is part of a wider process. According to the World Bank: “From a low initial level of $22 billion in 1990, FDI [foreign direct investment] toward developing countries is currently running at about $200 billion a year, some 2.5 percent of developing country GDP.” Developing countries currently attract about one-third of total FDI.

Amidst all the facts and figures which document the changes in the structure of the global capitalist economy, the most striking, and the most far-reaching so far as the perspective of socialism is concerned, is the growth in the global labour force. The entry of hundreds of millions of workers into the global labour market is an epoch-making development.

There are various estimates of the size of this transformation. In a paper prepared for a Federal Reserve Bank of Boston conference in 2006, Richard Freeman, a Harvard labour economist, estimated that the entry of China, India and the former Soviet bloc into the world market had roughly doubled the labour force in the market economy from 1.46 billion to 2.93 billion.

The International Monetary Fund provided an estimate of the growth of the global labour force in its “World Economic Outlook” published in May 2007. Weighting the labour force of each country by its participation in the global economy—measured by the ratio of exports to GDP—the IMF found that: “[T]he effective global labour force has risen fourfold over the past two decades. This growing pool of global labour is being accessed by advanced economies through various channels, including imports of final goods, offshoring of the production of intermediaries, and immigration.”

Most of the increase took place after 1990. East Asia contributed about half the increase, while South Asia and the former Soviet bloc countries accounted for smaller increases. While most of the absolute increase in the global labour supply consisted of less educated workers, the supply of workers with higher education increased by 50 percent over the last 25 years due to an increase in supply in the advanced economies, but also due to China.

These vast changes in the structure of the global labour force have had a major impact on the wages of workers in the advanced capitalist countries and the distribution of national income between wages and profits. The IMF notes that there has been a clear decline in the labour share of national income in the advanced capitalist countries since 1980. It estimates this shift to be about 8 percentage points.

The impact can be seen from this graph.

In his report to the Boston Federal Reserve conference, Richard Freeman concluded that: “The advent of China, India and the ex-Soviet Union shifted the global capital-labor ratio massively against workers. Expansion of higher education in developing countries has increased the supply of highly educated workers and allowed the emerging giants to compete with the advanced countries even in the leading edge sectors that the North-South model assigned to the North as its birthright.”

He estimated that the doubling of the global work force reduced the ratio of capital to labor in the global economy by 40 percent to 50 percent. In other words, as the supply of labour increases relative to capital, so its price—wages—must decline.

In July 2006, the Economist noted: “Last year, America’s after-tax profits rose to the highest as a proportion of GDP for 75 years; the shares of profit in the euro area and Japan are also close to their highest for at least 25 years... China’s emergence into the world economy has made labour relatively abundant and capital relatively scarce and so the relative return to capital has risen.”

The Financial Times noted on October 14, 2006 that British company profits were reported at their highest level in 2005, while median weekly earnings adjusted for inflation fell by 0.4 percent.

“It is the same story in all the rich countries of the west,” the report continued. “In a recent research note on the US economy, Goldman Sachs, the US investment bank, said: ‘As a share of GDP, profits reached an all-time high in the first quarter of 2006. Several factors have contributed to the rise in profit margins. The most important is a decline in labour’s share of national income.’”

The report cited a blunt comment from economists Stephen King and Janet Henry of HSBC Global Research: “Globalisation isn’t just a story about a rising number of export markets for western producers. Rather, it’s a story about massive waves of income redistribution, from rich labour to poor labour, from labour as a whole to capital, from workers to consumers and from energy users towards energy producers. This is a story about winners and losers, not a fable about economic growth.”

But the decline in the share of wages is not the only way in which profits have been boosted. Not only has the entry of China into the world market resulted in the cheapening of consumption goods, there has also been a reduction in the cost of industrial equipment. That is, in terms of the categories of Marxist political economy, not only has the rate of exploitation increased, due to the lowering of the value of labour power, but the organic composition of capital has tended to fall because of the cheapening of constant capital, thereby tending to lift the average rate of profit across the capitalist economy as a whole.

To be continued