As the first decade of the 21st century comes to a close, a good many artists and writers are attempting to gauge the impact on a human level of collapsing economies and the bankruptcy of hitherto accepted solutions to society’s problems.

These artistic efforts arrive in various forms: some successful, some unsuccessful, most confused. Many of the efforts take the form of dystopian novels that explore individual reactions to the surrounding maelstrom. Lacking a perspective on developments, such works often express a sincere sense of disquiet through the perceived threat to the individuals’ personal lives—i.e., the immediate consequences—without seriously challenging the reality of the surrounding society—i.e., the fundamental causes.

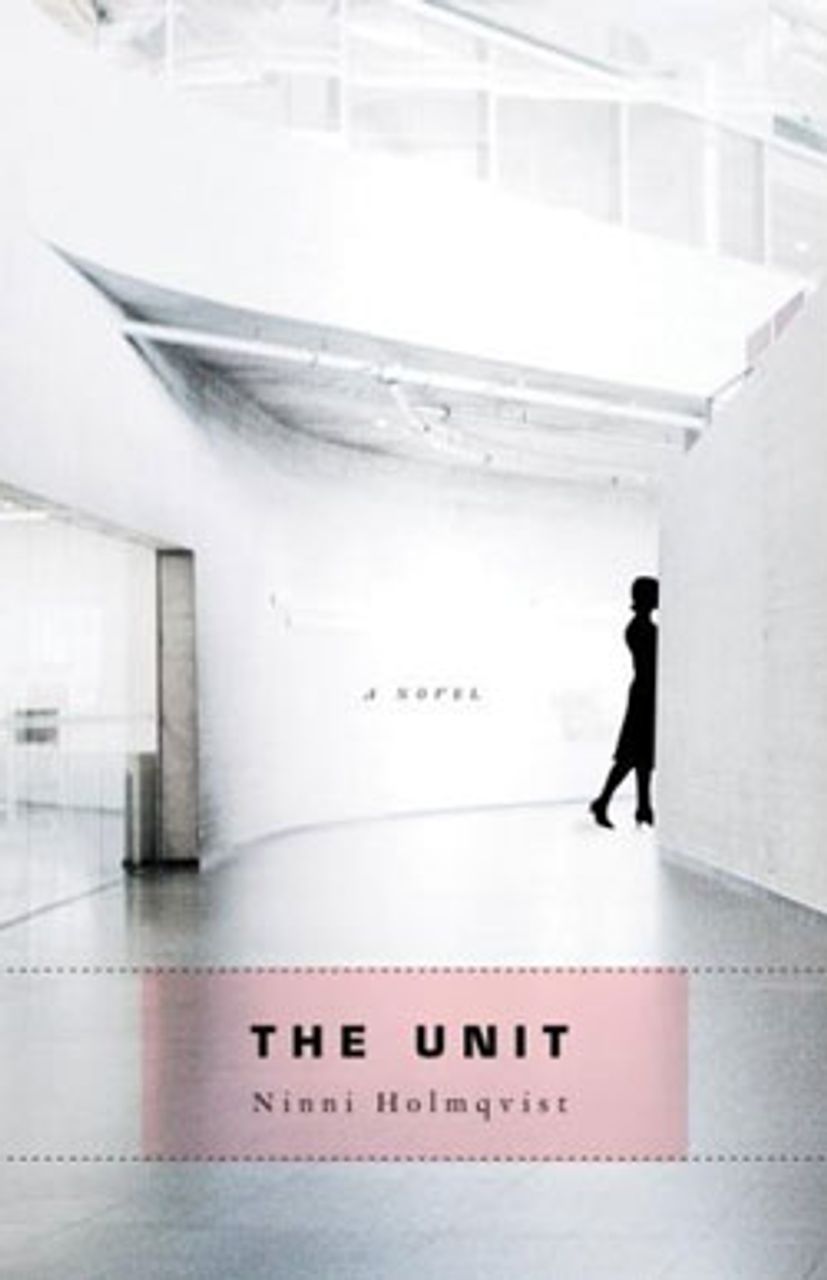

Such, for example, is the response of Swedish writer Ninni Holmqvist in her debut novel, The Unit (translated from the Swedish by Marlaine Delargy, Other Press, New York).

Holmqvist has taken to one of its possible logical extremes the drive for profit and its devaluation of art or culture by creating a fictional society in which people are divided into “needed” and “dispensable,” based upon whether the individuals in question have fulfilled the function of marrying and reproducing, creating more people for the state. The “dispensable” people are, to a large extent, artists, novelists, intellectuals and anyone else who has put his or her professional life ahead of biological “obligations.” The novel is disturbing and poses the question: who owns our lives and decides their value?

The society depicted in the novel—based on modern Sweden, but meant to represent 21st-Century advanced industrial society—condemns by law women past reproductive age and men over the age of 60 to “retirement” in so-called “Units,” where they are put to the only use their society finds for them: as biological material.

In The Unit, the promotion of the family as the basic and exclusive unit of society—a doctrine espoused by the Christian right in the United States, for example—has become legally enforced government policy. Those who choose not to have children are slighted as selfish, viewed with suspicion and designated as “dispensable.”

The narrator, a 50-year-old female novelist named Dorrit, is introduced to us as she stands before what was her home, waiting to be collected by representatives of the Unit, who are taking her to a secure and isolated facility to live out the remainder of her life.

We follow Dorrit as she checks into the “Second Reserve Bank for Biological Material,” a seemingly luxurious super-retirement facility, managed by improbably cheerful warders who emphasize the wonderful life she will enjoy there and the parties, theaters, art galleries and other social amenities provided for free. However, the true conditions of what can only be described as incarceration soon make themselves known.

For instance, the comfortable and well-equipped apartments assigned to the inmates are under constant surveillance. We learn that incomers are required to submit to intrusive and extensive medical and psychological evaluation.

This aspect of the Unit is reminiscent of “The Village” in Patrick McGoohan’s television series “The Prisoner” (1967-68), where former spies were isolated in apparent luxury to keep them from returning to normal society. It also reminds one of the enclosed, hedonistic metropolis in “Logan’s Run” (1976), where society consisted of nothing but young people who, on reaching the age of 30, suddenly vanished.

In the first example, former secret agents were perceived as dangers to the state, which attempted to corral them in a bland world of ease and phony bonhomie. In the latter, the pampering of the young citizens in an intellectual vacuum with lots of sex and technology was a combination of pacification and population control. The major difference between these two examples and The Unit, however, is that the protagonists in the earlier works resist by planning—or actually carrying out—their escape.

People in The Unit disappear too. Several of Dorrit’s new friends undergo alarming physical and mental deterioration after taking part in experiments, the purpose of which is never disclosed. But we hear nothing about resistance or escape. Even on those infrequent occasions when the seeming acceptance of the situation by the inmates falls way, and resentment and anger emerge in response to their situation, there is never any serious discussion—let alone questioning—of the political philosophy behind the devaluation of a large chunk of the population. There is no hint of a challenge to authority in the form of doctors and psychologists. There is no will at all.

All Holmqvist offers as explanation for this state of affairs is that a referendum was held at some time in the recent past and that by the time it came to the vote “opinion had shifted.” Shifted from what to what? We are not told. What lay behind the conclusion that age and non-parenthood were responsible for society’s ills? Why these particular criteria? Was it religious or economic? For that matter, why are so many spare parts required to maintain this society? Why are dangerous drugs and chemicals being tested on humans? Is the country at war? We are never offered insight into any of this.

The novel would have been greatly strengthened and made richer and deeper (and more convincing) if conditions in the wider community and its history had been discussed and fleshed out. After all, the Unit was created by a definite society, whose government has obviously spent a lot of time and money building and maintaining the Units. What were the conditions of this society before the Unit project was instituted? What are they now for those outside the Unit?

Characters occasionally mention that their government is a “democracy.” But what kind of democracy can this be? What notion of democracy have these people been persuaded to believe in? These questions are never explored.

Near the end of the novel, Dorrit’s psychologist asks her about the meaning of life. Dorrit replies that other people own her life. When asked who these other people are, she replies:

“We don’t really know. The state or industry or capitalism. Or the mass media. Or all four. Or are industry and capitalism the same thing? . . . And life is capital. A capital that has to be divided fairly among the people in a way that promotes reproduction and growth, welfare and democracy. I am only a steward, taking care of my vital organs.” [Emphasis added]

The author seems to be saying that the citizens of this regime believe ownership of one’s body by the state is democratic. It would have been interesting to know what social influences molded popular consciousness into accepting such a repellent notion. Nor is there a serious analysis of the “negative” thoughts and feelings that occasionally assail the occupants of the Unit. The characters seem to be ashamed of their feelings of anger and panic, yet the latter express honest human responses to an intolerable situation.

The story of The Unit appears to be a personal response to social wrongs on the part of the author. It comes as no surprise to discover that Holmqvist was born in 1958 and therefore falls into the exact age group and profession of her main character. The personal aspect of the choice of subject is also what helps limit it as a broader commentary.

The characters in the story of The Unit are all people like Holmqvist: creative, middle-class, middle-aged people. One of the primary unanswered questions in the book is what happens to childless people who are not from this social layer. Have they also been assigned to luxurious units?

There is a distinct navel-gazing quality to Holmqvist’s ruminations that is a hallmark of much recent fiction. Only the impact of events on the main character is considered, and this narrowness of vision results in little light being shed on society as a whole. Moreover, it has a (perhaps unintentionally) selfish aspect.

With all of its limitations, The Unit is interesting and worth reading if only for the questions it raises in the minds of readers as to the likelihood of such an authoritarian society emerging in the Western industrial countries, whether based upon age or any other social criterion. Holmqvist writes with a melancholy and nostalgia common to many novels coming out of Scandinavia, including the writing of Swedish author Henning Mankell, both in his Wallander detective novels and his other recent works, such as Depths (2006).

There is a disillusionment in these writers that goes beyond the stereotype of depressive Swedes and “melancholy Danes,” and no doubt has something to do with the collapse of the national-reformist, “Third Way” welfare state in the present global economic turmoil.

Holmqvist’s characters, for all their seeming sensitivity and compassion, seem detached and floating in a kind of anomie, where dreams and a longing for a better past are all that sustain them. Nonetheless, there are passages in the book—particularly a description of an art exhibit and its effect on the main character—that are beautifully realized, wherein we are made aware that there is humanity here, after all, waiting to get out.

On the other hand, “People who read books,” as the librarian of The Unit explains to Dorrit, “tend to be dispensable. Extremely.”