Edward Upward, who died last month, aged 105, was a remarkable figure. The last surviving member of the "Auden generation" of writers that emerged between the wars, Upward's literary career was devoted to the relationship between aesthetics and politics. His key works focus on his struggle to find an artistically truthful mode of expression that would fit with the political conceptions of the Stalinist Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), of which he was a member for 16 years.

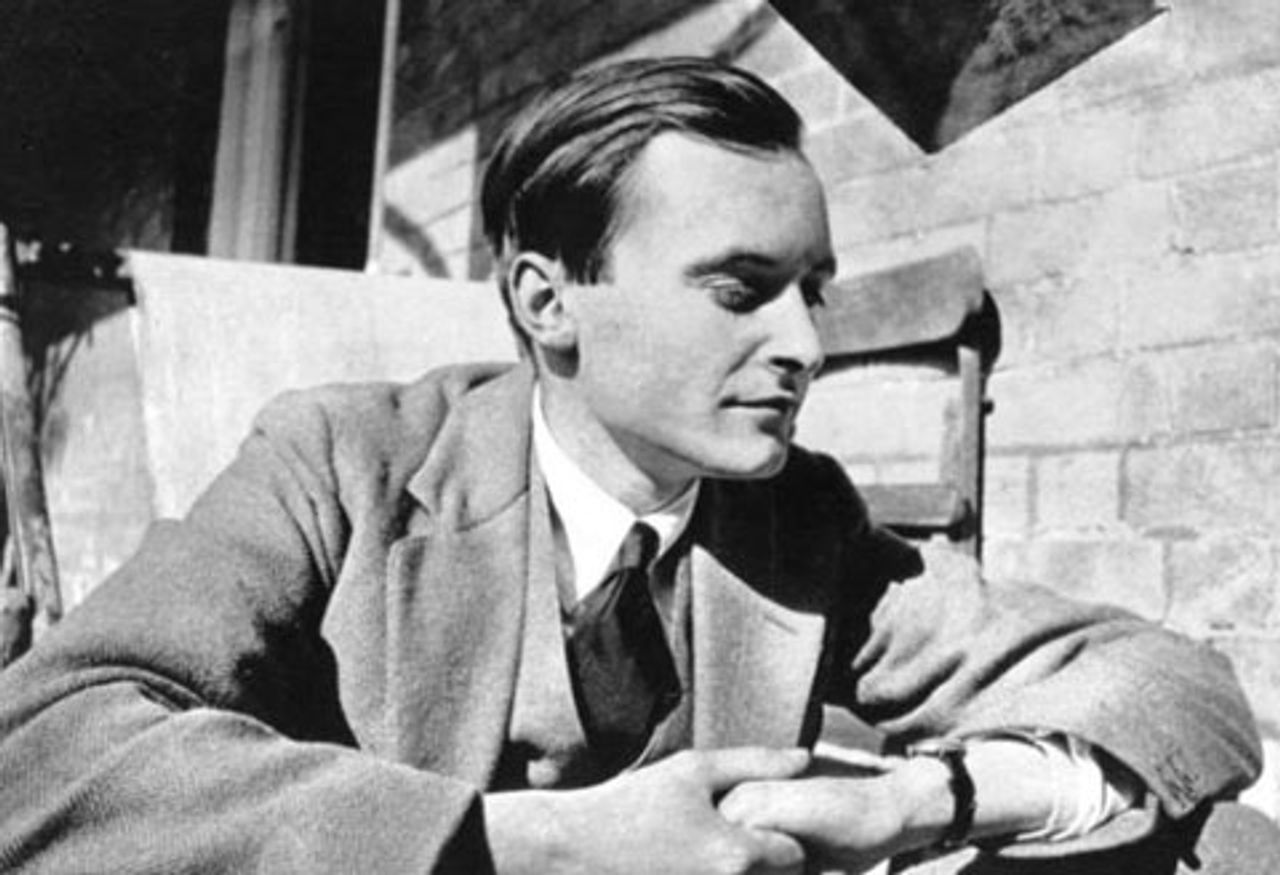

Edward Upward in the 1930s

Edward Upward in the 1930sUpward was born in 1903, the son of a doctor. He had a conventional middle class upbringing, against which he rebelled. He was unhappy at Repton School, until he met Christopher Isherwood, a fellow pupil, in the sixth form. They struck up an instant friendship. In 1938, Isherwood described Upward thus:

"Never in my life have I been so strongly and immediately attracted to any personality, before or since. He was a natural anarchist, a born romantic revolutionary."

They remained friends, and continued to show each other work in progress. Isherwood regarded Upward as "the judge before whom all my work must stand trial and from whose verdict there is no appeal."

The friends went to Cambridge together. Upward won a scholarship to read history at Corpus Christi College, switching to English for his last year. He aspired to be a poet. His poem "Buddha" won the Chancellor's Medal for English Verse in 1924. Upward was clear-eyed about his talents. In the autobiographical novel In the Thirties (1962), he describes listening to a friend's verse at this period. "Without any envy at all, and with happy admiration, [he] recognised that his friend's work was far better than anything he himself had done or ever could do."

Christopher Isherwood and W.H. Auden

Christopher Isherwood and W.H. AudenHe abandoned the idea of poetry after showing some of his verse to his younger friend W.H. Auden, whom he met through Isherwood. Auden "said it was not good and that was it," declared Upward. At the same time, Auden acknowledged the debt he owed to Upward, writing to him in 1930, "I shall never know how much in these poems is filched from you via Christopher [Isherwood]."

Upward's poetic sensibility was unleashed in his prose. Whilst in Cambridge, he and Isherwood produced a series of fantastic short stories set in the gothic-bucolic village of Mortmere. What Upward called the "surreal medievalism" of the Mortmere stories offered both writers a literary outlet for their rebelliousness. "[A]ll accepted moral and social values were turned upside down and inside out, and every kind of extravagant behaviour was possible and usual. It was our private place of retreat from the rules and conventions of university life," wrote Isherwood of the stories.

The Mortmere stories circulated in manuscript form amongst their friends, and their skill and invention became a landmark for the "Auden generation." Auden regularly read them to his poetry audiences. The pinnacle of the cycle, "The Railway Accident" (1928), was eventually published in 1949 under the pseudonym Allen Chalmers, the name Isherwood used for Upward in his autobiography Lions and Shadows (1938). Upward later destroyed most of the Mortmere manuscripts, and did not allow the remaining fragments to be published until 1994. If the Mortmere stories express an instinctual rebelliousness and hostility to what Upward termed the "poshocracy," it is clear that Upward was also striving for a more lasting and articulate response to inequality.

After Cambridge, he worked as a private tutor whilst he struggled to write a novel. Reading In the Thirties, one is struck by his seriousness about the craft of writing, and how difficult he found it to commit material to paper. That novel, set in a golf club, came to nothing, but he was working towards the biggest decision of his life.

Upward had been reading Marx, and was trying to find ways of making his writing socially relevant and artistically truthful. Like the best elements of his generation, he was moved and inspired by the Russian Revolution. After a visit to the Soviet Union in 1932, he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain. It was a move he had been considering for some time. He was a member of the CPGB until 1948. He met his wife, Hilda Percival, there. They had two children.

Upward's commitment to Marxism played a significant part in bringing several other authors around the CP. Stephen Spender said his "vaguely distressed consciousness began to formulate itself along lines laid down by Marxist arguments" following discussion with Upward. Auden, too, was influenced by Upward's politics. Unlike Auden and Spender, Upward remained loyal to his understanding of Marxism, which was to form the content of his subsequent writing.

In his semi-autobiographical writings covering this period, like his first novel Journey to the Border (1938, revised 1994), Upward expresses ambivalence about his earlier flights of imaginative fancy. He seems to have felt that the energetic imagination that created Mortmere had also taken him too far from reality. It would be a simplification to say that he became a "Socialist Realist" writer, although that is the claim made now by contemporary British Stalinists. The reality of his political and artistic relationship with Stalinism is more complicated than that.

Upward was attracted to the CPGB because he identified it as the party of Lenin, as the party that had led the Russian working class during the Revolution, but by 1932 the CPGB had abandoned and betrayed that heritage. Internationally, the Stalinists were hounding out the Trotskyists of the Left Opposition. This battle against the opposition took place in every sphere, including cultural life. Spender, in his return to liberalism, wrote a vicious attack on communism. In The God That Failed (1949), he recalled Allen Chalmers (Upward) assuring him that the Stalinist purges in the Soviet Union were of little account compared with the glories of socialism. Throughout Upward's trilogy of autobiographical novels, known collectively as The Spiral Ascent, there is a repeated refusal to believe the possibility that the Stalinists might be persecuting genuine communists.

The second volume of the trilogy, The Rotten Elements (1969), deals with the internal disputes in the CPGB following the Second World War, which led to Upward and his wife leaving the party in 1948. Their disputes were of a somewhat secondary character. They disagreed in particular with the party's promotion of the productivity drive demanded by the Labour government. And even as Alan Sebrill (the Upward character) disputes the political line of the CPGB, he is at great pains to assure the leadership that he is no Trotskyist. ("As for the suggestion that we are Trotskyites...I need only point out that all Trotskyites without exception are opposed to Stalin and to the Soviet government, whereas we support Stalin and the Soviet government.") Later, after the Sebrills have left the party, they welcome the criticisms of Moscow made by the Chinese CP without drawing any further conclusions about Stalinism generally.

There is much in The Spiral Ascent of historical interest about the inner life of the CPGB, particularly for its middle class members. Shortly after joining the party, Upward took a job teaching English at a minor public school, where he was to remain employed until his retirement. There is an amusing scene in which Alan and Hilda Sebrill attempt to persuade a Swedenborgian minister who has applied to join the party to remain in his "influential" position within the church.

Upward saw the CP as the political body he had been looking for that would connect him with the working class. In turn, he sought to make his work directly political, and to reflect the political line of the CPGB. In an essay written in 1937, "Sketch for a Marxist Interpretation of Literature," he insisted that unless a writer "has in his everyday life taken the side of the workers, he cannot, no matter how talented he might be, write a good book." From this he rejected the "literary allegories and fancies" that had formed the basis of his earlier work.

The negative impact can be seen on his work. Reading The Railway Accident and Other Stories, which covers the period 1928-1942, one cannot but be struck by the squeezing out of the poetic and the imaginative, and their attempted replacement with the earnest and literal. The novels dealing with his turn towards, and membership of, the CPGB all show him trying to leave behind the contemplative study of poetic life he had considered whilst at university.

There is a gulf between such a mechanical view of artistic perception and Marxist literary criticism. As Aleksandr Voronsky noted, "Those who defend only ‘rationalistic depiction' don't have even a remote conception of the essence of art."

Stalinism increasingly advocated a new, proletarian art based on socialist realism. In part, this was aimed at crushing the more far-sighted Marxist critics, who were lined up in the Left Opposition. Upward does not mention Trotsky's artistic writings in The Spiral Ascent or those of Voronsky. But Voronsky wrote extensively on the very questions that occupied Upward throughout the 1930s. In his remarkable essay "The Art of Seeing the World," Voronsky addressed exactly the question of contemplation that preoccupied and hampered Upward:

"People say that since such states are contemplative," wrote Voronsky, "supposedly they are passive, and therefore, for the artist of our times, for people who are reconstructing life, they are inappropriate. These are very mistaken assertions...because in actual fact, we are dealing with very complex creative feelings. They are not contemplative since the artist, during these moments, makes his best discoveries of the world for us and strips away the veils; they would be passive if the artist limited himself to simple descriptions or with making a photographic copy of reality, but we are talking about completely different relations to the world."

Yet, for all that Upward basically defended so-called Socialist Realist conceptions of art, he was no simple Stalinist hack. His work even at this period continues to strive for artistic truthfulness, which it often achieves by its poetic expression. Stephen Spender described Journey to the Border (1938), Upward's novel about a young artist coming towards the workers movement, as containing "some of the most beautiful prose poems of the century." Many of the contemplative passages that he felt betrayed his political duty more than fulfilled his artistic vision. The novel, too, contains passages of bitter comedy that would not have been out of place in Mortmere.

Upward felt continually torn between his political duty and his artistic responsibility.

Never a prolific writer, the struggle to address his political responsibilities in artistic terms seems to have increased the pressures on Upward. The first two volumes of The Spiral Ascent largely cover his failure to write the poems he thought he should be writing. He wrote less and less during his period in the CPGB, but the questions were not forgotten. There is an extraordinary chapter towards the end of The Rotten Elements in which these arguments resurface with full force.

After the Sebrills have left the party, a local member brings round copies of Soviet Literature. He and Alan argue over literary questions. Alan voices his concern that "literary quality matters much less to the Party than...political quality." He finally expresses the artistic vision that drives him: "Poetry is not just something the poet adds as a sort of decoration to a political or moral statement that he wants to make. Poetry deals with life directly and in its own specific way; it has its own language and laws and its own kind of truth which is not the same as political or moral truth." The party member disagrees, arguing that there is "only one kind of truth...I'll call it scientific truth."

Sebrill passionately and articulately defends poetic truth. "Poetic truth—and artistic truth in general—is emotional truth communicated in a specially skilled way," he explains. He is forced to recognise that these qualities are missing from much of the Stalinist literature he has been reading. Indeed, the local party member argues against him that "depicting life is the proper function of all art." Then how, asks Sebrill, "does art differ from—for instance—sociology?"

One is reminded of Voronsky's treatment of precisely this question in 1923 in "Art as the Cognition of Life": "Like science, art cognises life. Both art and science have the same subject: life, reality. But science analyzes, art synthesises; science is abstract, art is concrete; science turns to the mind of man, art to his sensual nature. Science cognises life with the help of concepts, art with the aid of images in the form of living, sensual contemplation."

It is difficult not to see Upward's writing being choked by the politics he espoused. He published little between 1938 and 1962, although he served on the editorial board of The Ploughshare, organ of the Teachers' Anti-War Movement. His disputes both inside and outside the CP created an intense personal crisis, culminating in a breakdown. This crisis is described in The Spiral Ascent, although within the limits of his refusal to address the questions of Stalinism. In the final volume, No Home But the Struggle (1977), Alan Sebrill finds some kind of reconciliation between his art and his politics only by joining broader campaigns.

He had trouble finding a publisher for The Spiral Ascent, which he began in 1954. Leonard Woolf, who had published Journey to the Border, thought In the Thirties contained too much about communism. Heinemann, who published the first two volumes, initially refused to publish No Home But the Struggle until the Arts Council offered to underwrite the project. The trilogy is currently out of print in Britain.

Upward had something of a renaissance in his later years. A sympathetic publishing house issued new collections of stories, along with memoirs of Auden and Isherwood. His final collection of stories, A Renegade in Springtime (2003), was published to mark his centenary. Many of these stories dealt with the political concerns he had tackled throughout his life. Upward was a serious thinker and artist. He was unable to overcome the restrictions imposed on his art by the political and artistic conceptions promoted by Stalinism, but his defence of artistic truth and expression is worthy of study.