Filmmaker Roman Polanski, as of this writing, remains in a Zurich jail cell, while his lawyers fight the efforts by US authorities to extradite him. Polanski pled guilty more than 30 years ago in Los Angeles to unlawful sex with a young teenage girl, then fled the country when the judge in the case reneged on a plea bargain agreement and threatened to sentence the director to a lengthy prison term.

Every aspect of the case against Polanski reeks of dishonesty, hypocrisy, and expediency. It has far more to do with current political and economic interests than with an incident that occurred in 1977 and whose two participants have long ago wished to see put to rest.

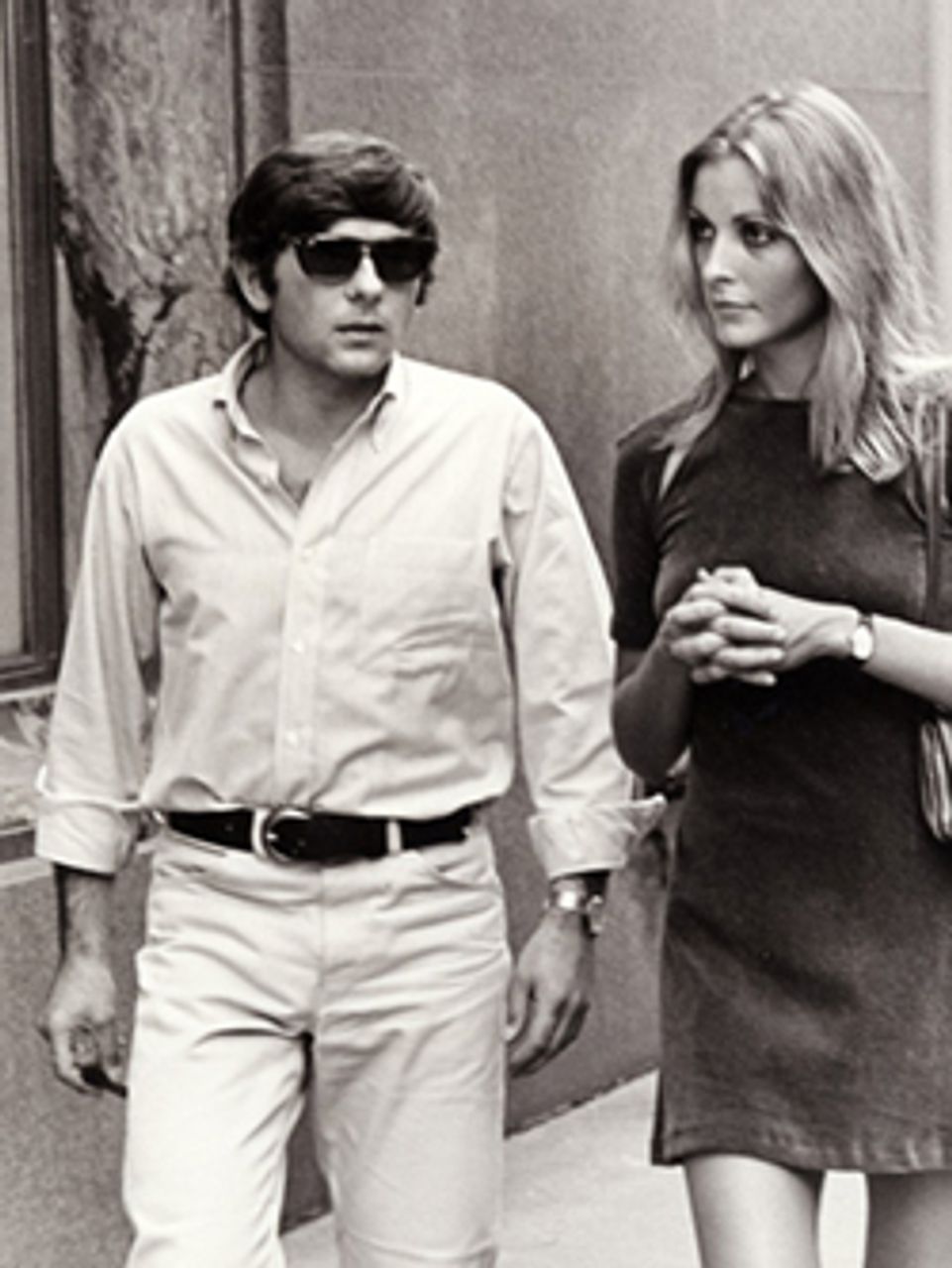

Roman Polanski, circa the 1960s

The central concern of the Swiss authorities, by all accounts, is in this instance—as in every instance—the protection of their financial institutions. Embarrassed by a corruption scandal involving UBS and concerned about further investigations into their banks, the Swiss tipped off American officials that Polanski would be in Zurich for a film festival as a means of appeasing Washington.

For Los Angeles authorities, the vindictive Polanski witch-hunt serves the ends of settling a score with an individual who poked them in the eye. The American political establishment generally regards the Polanski affair as a useful means of further stoking up social backwardness and hysteria over alleged sex offenses.

Other factors may have played a role, including the recent efforts of Polanski’s lawyers to have the case dismissed, based on the evidence of judicial misconduct, and their charge that Los Angeles officials had shown no seriousness about pursuing the director in recent years. It is at least intriguing to note that Polanski’s new film, The Ghost (adapted from the novel by Robert Harris), uncompleted and unreleased because of the director’s arrest, accuses a fictional former British prime minister (clearly based on Tony Blair) of war crimes and other perfidious acts.

It should be evident to anyone who thinks about it for a moment that the case against Polanski involves a political agenda. His continued prosecution represents an injustice and conforms to reactionary aims.

The fake populist claim that Polanski is a member of the “Hollywood elite” receiving special treatment is false, and even sinister. It echoes (and encourages) the repeated claims of anti-intellectual and often anti-Semitic forces that the entertainment industry is a hotbed of sin and corruption sapping the nation’s “moral foundations.” To join in the effort to set “Middle America” against “Hollywood,” as a series of liberal commentators at the Nation and Salon have done, is unprincipled and politically reprehensible.

In reality, certain individuals (Michael Jackson and others) are picked out because they are wealthy celebrities and served up as human sacrifices to the most backward layers of the population, in an effort to divert their confused but seething anger over deteriorating conditions of life. The punishment of the rich and famous provides a vicarious (and illusory) satisfaction in such cases. It is not accidental that the manipulated outrage against Polanski comes in the midst of the deepest economic crisis since the Great Depression and a continuing flood of layoffs, wage cuts, foreclosures and personal bankruptcies.

Beyond the political and legal questions, there is something more involved here. After all, Polanski has considerable artistic gifts. In discussing the concerted effort to lock him up, we are obliged to consider his artistic contribution.

Polanski himself, through his French lawyer, Hervé Temime, has termed “counterproductive” arguments from defenders citing his artistry as an exculpatory factor. The filmmaker, Temime told reporters, felt that some of the commentary “was perceived as support for the immunity of an artist, and I think that’s a false debate.… He has never demanded special treatment for himself or his career.”

Of course, there is no “immunity” for the artist; we would not even consider the question in those terms. However, Polanski’s artistry and body of work demonstrate that he is not a sociopath; he is clearly not a pedophile, which would in any case raise the issue of treatment more than punishment

Does it matter at all then that Polanski is a remarkable artist? We believe it does.

The evidence demonstrates that Polanski is not a sexual predator, but a gifted artist capable of colossally bad judgment.

As a preface, it must be said, the circumstances of his life, dismissed by his self-righteous enemies as irrelevant (the director tends to discount them too, insisting that he doesn’t “linger” on unhappy memories), would be taken into account in any humane consideration of his personal difficulties. (That the case should most likely have been thrown out years ago on the grounds of judicial misconduct alone is another matter altogether.)

To be born in 1933, the year of Hitler’s ascension to power, was perhaps a tragic omen. Polanski’s family returned to Poland from France in 1936, and after the outbreak of the Second World War were forced to move into Krakow’s Jewish ghetto. As a boy, Polanski witnessed many horrors. One day, for instance, he saw a German soldier shoot and kill an old woman simply because she couldn’t keep up with a group of other women being herded down the street. “There was a loud bang, and blood came welling out of her back,” he later recalled. Certain memories and images from this period of Polanski’s life were incorporated into the award-winning The Pianist, based on the memoirs of Polish Jewish musician Wladyslaw Szpilman.

Nazi Stormtroopers force march Jews through the streets of Warsaw, 1943

Nazi Stormtroopers force march Jews through the streets of Warsaw, 1943The following experience inspired the direction of a scene in his film version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth: “The SS officer had searched our room in the ghetto, swishing his riding crop to and fro, toying with my teddy bear, nonchalantly emptying out the hatbox full of forbidden bread.” Polanski’s mother was eventually deported to Auschwitz, where she died, and he witnessed his father being marched off to another concentration camp (where he survived). Polanski barely escaped deportation to a camp. He was hidden first in Krakow and later in the countryside, largely fending for himself. More than 90 percent of the 3.5 million pre-war Polish Jewish population were dead by 1945.

In the brutal conditions of postwar Poland, Polanski was attacked by a psychopath (already guilty of three murders) who struck him on the head repeatedly with a stone and left him for dead.

In 1969, his wife—actress Sharon Tate, eight and a half months pregnant—and three friends were brutally murdered in Los Angeles by followers of cult leader Charles Manson. Before the real culprits were apprehended, the American media had a field day attempting to link Polanski, or at least his “hedonistic” lifestyle, to the horrible tragedy.

It is difficult to conceive what effect all this must have on the nervous system.

And what about Polanski’s artistic efforts themselves? Is he a serious figure? How have his films stood the test of time? Moreover, has he pursued themes that belie his media image as a “monster” and a “pervert”?

There is no possibility here of treating in detail a body of work that spans half a century, but certain points can be made.

Polanski began making short films in Poland in the late 1950s and directed his first feature film, Knife in the Water, in 1962. One can raise all sorts of criticisms, artistic and ideological, about his efforts, but it is difficult to think of more than a handful of directors globally who began working in the 1960s, or earlier, and continued to make important films into the first decade of the twenty-first century.

Polanski has expressed a variety of sentiments in his films, but a constant has been a concern for the fate of the vulnerable individual—often a child, an immigrant, a young woman, a victim of persecution (Tess, The Tenant, Oliver Twist, Death and the Maiden, The Pianist, as well as Chinatown in its way)—in a generally menacing environment, threatened by different forces, from the insensitivity or social prejudices of others to the outright violence and cruelty of the authorities.

Sometimes, in extreme cases, the external world proves so crushing and destructive in Polanski’s films (in Repulsion and The Tenant most obviously, but there are also elements of this in Cul-de-Sac, Rosemary’s Baby, Bitter Moon, Death and the Maiden, even Macbeth and The Pianist) that it invades the individual and brings about an internal collapse.

Could anyone reasonably argue, given the difficulties of the last three quarters of a century, that in representing such a frightening state of affairs Polanski has not offered insight into important aspects of modern existence? In other words, Polanski has applied himself consistently—sometimes successfully, sometimes unsuccessfully, but seriously, at any rate—to one of the central questions of our time: “the conflict between the individual and various social forms which are hostile to him” (Leon Trotsky and André Breton, Manifesto: Towards a Free Revolutionary Art).

His terrifying experiences in Nazi German-occupied Poland surely prepared him for that. Stalinist repression in the so-called “People’s Republic of Poland” under the rule of the “Polish United Workers Party” would have added to his skepticism about the powers that be in modern society. His encounters with a spiteful American legal system and media have probably not improved his opinion of media-organized “public opinion” and the forces of law and order.

Polanski began his artistic career as a child actor on radio and with a puppet theater. He also “became a well-known street person” in Krakow, according to biographer Barbara Leaming, “little, loud and aggressive.” He landed a part in Andrzej Wajda’s A Generation, released in 1955, the first part of the renowned trilogy (along with Kanal and Ashes & Diamonds).

Poland never experienced “socialism,” much less “communism,” but the formation of the postwar Stalinist regime in Poland brought certain social benefits to the population—rooted in the nationalization of basic industry and related measures—that were, in the end, surviving gains of the Russian Revolution of 1917, extended into the Eastern European bloc countries.

The National Film School in Lódz, Poland

The National Film School in Lódz, PolandPolanski was able to attend the National Film School in Lódz in the mid-1950s, at the time one of the finest in the world. He told interviewers Pascal Bonitzer and Nathalie Heinich in 1979 that “Polish technique was developed by filmmakers who were in the Soviet Union during the Second World War. And Soviet cinematography was based entirely on the principles of American production which had been studied and copied in the post-[Russian]revolutionary era, at a time when they had as much enthusiasm as the Americans have today.”

He told a Playboy magazine interviewer in 1971 that the school’s intense, five-year program was “advantageous.” Polanski explained: “Besides all the practical training, like editing, camera operating, etc., you had courses in the history of art, literature, history of music, optics, theory of film directing—if such a thing exists—and so forth. The first year was very general and theoretical, and you got to know intimately the techniques of still photography, which is essential, I think, for anyone who later wants to be an expert in cinematography. The second year, the students made two one-minute films of their own. The third year, a documentary of eight to fifteen minutes. The fourth year, a short fictional film of the same length; and then in the fifth year, you made your diploma film, which could go up to 20 minutes.”

Orson Welles

Orson WellesPolanski explained that “The school was tightly connected with the Polish film archives and we could see anything we wanted.” Elsewhere, he notes that the students were divided into artistic factions, “Personally, I was part of the [Orson] Welles group, but there were also groups of neorealists and students who liked the heroic Soviet cinema.”

He left the film school in 1959, he told Playboy, “with very firm aesthetic ideals about films.… For me, a film has to have a definite dramatic and visual shape, as opposed to a rather flimsy shape that a lot of films were being given by the [French] Nouvelle Vague, for example, which happened in more or less the same period. It has to be something finished, like a sculpture, almost something you can touch, that you can roll on the floor. It has to be rigorous and disciplined—that’s Citizen Kane vs. The Bicycle Thief.”

It is worth citing these comments at length. They indicate some of Polanski’s artistic and intellectual advantages at the outset of his career: a firm grounding in film technique (a commentator notes that his “collaborators on Rosemary’s Baby, his first American film, were astonished at his exacting camera requirements and precise understanding of the optics and geometry of lenses” [Mark Cousins, “Polanski’s Fourth Wall Aesthetic,” in The Cinema of Roman Polanski: Dark Spaces of the World]); a thorough knowledge of film history and an orientation toward some of its most complex, aesthetically exacting figures (as a member of the self-declared “Welles group”); participation in a seething artistic environment that was a relative oasis of freedom in Stalinist Poland; an aversion to nationalism, which has proved fatal to more than one Polish filmmaker (“These subjects never interested me and from the start I worked outside nationalistic interests,” he told an interviewer in 1992); and despite his avowed anti-communism, Polanski had at least enough historical understanding to know that the Russian Revolution had generated “enthusiasm” among artists until the Stalinist clampdown of the 1930s.

It is perhaps telling about modern history that knives should figure so prominently in the work of one of its major artistic figures. In Polanski’s first completed short at the Lódz film school, Murder, only two minutes long, a man enters another’s room, stabs and kills him. We see the older man’s plump, complacent face and demeanor, fleetingly, only as he turns to leave. Knives (or other sharp blades) feature prominently in Repulsion, Rosemary’s Baby, Macbeth, Chinatown, and Tess.

Knife in the Water

Knife in the Water

And Polanski’s first feature, after all, was entitled Knife in the Water. In that film, a couple, Andrzej and Krystyna, nouveau riche Poles, reluctantly pick up a young hitchhiker, a poor student. They own a nice auto, like an “embassy” car, says the young man, and a boat. They are going sailing.

The two men, from the start, go at each other. Andrzej invites the younger man to go along with him and his wife for the day, almost as a dare. “So you want to go on with the game?,” says the student. The reply: “My boy, you are no match for me.”

Tensions mount on board the sailboat, as the older man, a well-heeled, arrogant (and generally unpleasant) sportswriter, pits his nautical skills and savoir-faire against the other’s youth and good looks, with the young wife, presumably, as the prize. The hitchhiker’s most valued possession is a knife of the switchblade variety. It becomes central to the conflict between the men.

Andrzej needs to control everything and everyone around him. Later, when the student gains a measure of emotional revenge, Krystyna tells him, “You’re not one bit better than he is, you understand? He used to be the same as you.… And you’d really like to be the way he is now. And you are going to be, as long as your ambition holds out.”

Numerous commentators agree that the main issue in Knife in the Water is a “struggle for power.” Andrzej himself says, “If two men are on a boat, one man is skipper.” A critic writes, “Power, and the violence used to sustain it, emerged as central elements in Polanski’s cinema” (Herbert J. Eagle, “Power and the Visual Semantics of Polanski’s films”).

No doubt. But the battle captured beautifully in black-and-white (with hints of Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai) by Polanski and his co-screenwriter Jerzy Skolimowski (the future filmmaker: Barrier, Deep End, Moonlighting) reminds one of siblings quarreling violently. One wants to say: it isn’t their fault. Someone else has set them at each other’s throats. Something is wrong in the whole situation.

Andrzej and the college student are struggling so fiercely over a knife, over an attractive, but rather passive woman, who doesn’t seem terribly interested in the outcome, because, in reality, neither one of them has any real control over his life. The slightly overwrought character of the film, in the end, comes from everybody’s social powerlessness (including the filmmakers’). The ultimate source of unhappiness is a repressive society, rife with inequalities and hypocrisies, that cannot be criticized openly.

Polanski then left Poland for good and made his first feature film in English, Repulsion, released in the US in October 1965. Catherine Deneuve plays a repressed young woman who shares an apartment with her sister. Also an outsider, Carol is a Belgian working in a London beauty salon. When her sister leaves on vacation, Carol suffers a nervous breakdown, hallucinates, and ends up slashing two men, an attractive suitor and her lecherous landlord.

Years ago, the film terrified me out of my wits (I recall spending a good deal of the time more or less under my seat), especially the sequences in which arms come out of the walls and reach for the unfortunate girl. On a more recent viewing, it seems somewhat dated and also a little overwrought. Again, the effort to cram all the fearfulness of postwar life into a purely psychosexual framework overburdens the drama. Repulsion sags under the weight and feels contrived as a result.

Cul-de-Sac

Cul-de-SacOne might say some of the same things about Cul-de-Sac (1966), except that it is a good deal more fun, at least in parts. Two wounded gangsters (Lionel Stander and Jack MacGowran), following a botched holdup, arrive at an isolated castle in northern England inhabited by an ex-businessman and his wife (also markedly different in age), George and Teresa, played by Donald Pleasance and Françoise Dorléac (Deneuve’s older sister, who died tragically in an auto accident in June 1967).

One critic (Paul Coates, “Cul-de-Sac in Context: Absurd Authorship and Sexuality”) comments that the film “can be situated in the Polish and English absurdist tradition, to which it is arguably the most closely related of all Polanski’s features, with the possible exception of The Tenant.”

An attraction for absurdism and related trends is clearly evident in Polanski’s art. The influence of Samuel Beckett, as well as Franz Kafka and blackly comic Central European traditions, is present in his early Polish shorts (Two Men and A Wardrobe, The Fat and the Lean, Mammals). The conjoining of sexual aggression and class tension brings Harold Pinter’s writing to mind, including his film work with Joseph Losey (The Servant).

The somewhat too tempting appeal of absurdism is not difficult to figure out, taking into account Polanski’s personal history and the general state of things in postwar Europe: a shattered economy and population, the resulting horror with fascism, the discrediting of “communism” as a result of the crimes of Stalinism—all of this producing an intellectual impasse (reflected in existentialism and other philosophical trends) of an epochal character.

Whether Polanski was conscious of it or not, the ideological atmosphere and physical conditions of life in postwar Eastern Europe, where the regimes set themselves the historically ludicrous goal of building isolated socialist states, were elements too in encouraging his absurdist sensibility. The image of Sisyphean-like, repetitive, and pointless labor recurs in a number of the early short films, in Knife in the Water, and even in Cul-de-Sac and The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967).

In any event, Cul-de-Sac has its pleasures, especially the initial, relatively lighthearted interplay between Stander (a victim of the Hollywood blacklist), Pleasance, and Dorléac. Again, sexual and other power struggles ensue, with a rather murky outcome—the gangster dead, the young wife fled, and George curled up in a fetal position on an outcropping as the tide comes in. A “dead end” (cul-de-sac) indeed, but from what precisely?

Among other things, it’s possible—although it may not have been the meaning of Polanski and longtime collaborator, screenwriter Gérard Brach—to interpret the film loosely as a comment on Britain’s declined and decayed state. The presence of an American thug, a dying Irishman, and an irresponsible Frenchwoman, all creating difficulties for the retired, wealthy and nervous Englishman on his secluded, island home is at least suggestive.

The Fearless Vampire Killers

The Fearless Vampire KillersPolanski disowned The Fearless Vampire Killers (or Dance of the Vampires), shot in England and Italy, after its producer Martin Ransohoff severely re-edited the film and made it incomprehensible from the director’s point of view. Still, there are the delightful performances of Jack MacGowran as the inept “vampire killer,” Professor Abronsius, and Polanski himself as Alfred, Abronsius’s equally fumbling assistant. Polanski met his future wife, the ill-fated Sharon Tate, on the film, in which she played one of chief vampire Count von Krolock’s (Ferdy Mayne) comely victims.

The film has something of the flavor of a Central European Jewish tale, understated, droll, earthy, taking a sharp-eyed but still sympathetic and amused view of humanity. And there is the lovely moment when “Shagal,” the Jewish inn-keeper (named no doubt for the modernist painter, who frequently depicted Eastern European Jewish village life), who has himself become one of the “living dead,” enters the bed chamber of the blonde servant girl he’s been lusting after.… When she holds up a crucifix—in the time-honored tradition—to ward him off, he scoffingly tells her: “Have you got the wrong vampire!”

Rosemary's Baby

Rosemary's BabyRosemary’s Baby, Polanski’s first Hollywood film (and major success), for Paramount Studios, shot in the fall and winter of 1967 and released the following June, is a story of the occult. Polanski hastened to assure an interviewer, “You don’t have to be superstitious to enjoy a fantasy.… Myself, I am down to earth in my philosophy of life, very rationally and materialistically oriented, with no interest in the occult.”

The story, about a young woman in New York whose ambitious husband makes a pact with a group of devil worshippers and offers her up as a receptacle for Satan’s child, is one of the so-called “apartment trilogy” (along with Repulsion and The Tenant), which treats the behavior of “people under stress” in confined spaces, with some of that behavior stemming from the very fact of being in a confined space, comforting and alarming at the same time.

(The boats in Knife in the Water and Bitter Moon, and the isolated castles or houses in Cul-de-Sac, Macbeth and Death and the Maiden are all, in their own ways, confined spaces—as is the apartment in which Wladyslaw Szpilman is obliged to remain for a time, at the peril of his life, in The Pianist, and Fagin’s lair, where Oliver is held against his will in Oliver Twist.)

All sorts of psychological issues present themselves in connection to this attraction for and repulsion from enclosed spaces, but at the center of them all probably lies the image of the sealed Krakow ghetto, frightening in itself, but the exit from which is even more frightening.

Rosemary’s Baby is a fantasy, and a well-done one at that. The filmmakers assembled an excellent cast, including Mia Farrow (although she was not his first choice), John Cassavetes as her selfish, opportunist actor-husband, and veteran character or stage actors Ruth Gordon, Ralph Bellamy, Sidney Blackmer, Maurice Evans, Elisha Cook Jr., Patsy Kelly, Phil Leeds, and Hope Summer.

The victim of her husband’s careerism and her sinister neighbors’ plans for her, Rosemary (Farrow) suffers horribly in her pregnancy. She turns pale and at first (unaccountably) grows thin; she’s in constant pain. Her elegant, spacious Upper West Side apartment becomes a prison cell, a place of torture. Those she reaches out to, when she realizes the nature of the plot, betray her. The film builds up a disturbing level of paranoia, at the same time as it maintains, until the very end, its peculiar sense of humor.

Roman Polanski attended the Cannes film festival during the May-June 1968 events, the massive general strike that shook French capitalism to its foundations. Contrary to myth (for example, in Vanessa Redgrave’s autobiography), he did not support the leftist attempt to shut down the festival that year. As he makes clear in his own autobiography, Polanski found the “revolutionary” filmmakers’ efforts rather self-indulgent and even “absurd,” which they may well have been, to a degree.

Nonetheless, whatever his ambivalence or even hostility, the experience of a mass movement in the West against capitalism (“By this time the general strike was spreading throughout France. Train and plane services were grinding to a halt, gas stations running dry. Exhibitors began to pack up and go home, and the festival ended in complete disarray,” he writes) had to have had an impact on him, as opposed to the experience of a later generation of “dissidents” in the Stalinist countries.

Polanski with Sharon Tate

Polanski with Sharon TateIn August 1969 tragedy struck when the so-called “Manson family” members murdered the pregnant Sharon Tate and four friends at the Los Angeles home Polanski and Tate shared. He was in Europe on a film project at the time.

Two years after the tragedy Polanski told the interviewer from Playboy: “Sharon was the first woman in my life who really made me feel happy. I mean literally aware of being happy. That’s a very rare state. Strangely enough, about a week or two before her death, I remember an instant when I was thinking of it, and I was actually thinking: ‘I am a happy man!’ … I also remember thinking—and here is my middle-European background, probably—I remember thinking: ‘This cannot possibly last. It’s impossible to last.’ And I suddenly got scared. I was thinking that you can’t maintain such a status quo. I didn’t have anything tragic in mind, but I was afraid, being quite a realist, that such a state cannot last indefinitely.”

Macbeth

MacbethPolanski’s next film was an understandably bleak version of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, filmed in North Wales and released in 1971. The director explained that after his wife’s murder, “everything I was considering seemed futile to me. I couldn’t think of a subject that seemed worthwhile or dignified enough to spend a year or more on it … As a kid, I loved Shakespeare, and when I was a teenager I saw Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet 20 times. I always had this great desire to make a Shakespearean movie some day, and when I finally decided I must go back to work, I thought to myself: ‘That’s something I could do, that’s something I could give myself to. That’s worth the effort.’”

Polanski adapted the play along with left-wing British theater critic Kenneth Tynan. Their version (perhaps inspired too by well-known comments from the German playwright Bertolt Brecht) emphasizes the shabby, dirty, provincial character of the medieval Scottish nobility’s existence. Pigs run through one castle’s grounds. The witches, not three, but a crowd, are ugly, ill-clothed, sometimes unclothed. Polanski and Tynan present Macbeth’s murder of Duncan, normally done offstage, in all its chaos and painfulness, as the usurper jabs at the reigning king with his dagger.

Macbeth has a perpetually moving frontline of violence and treachery, insecurity and blood. It contains some of the bitterest, grimmest lines in Shakespeare, reaching a high point in the famous soliloquy, “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,” which ends with Macbeth indicting life as “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Polanski’s is an intelligent, creditable version of Macbeth, with many picturesque and striking moments. However, by and large, the film lacks the necessary intensity and fury. Jon Finch and Francesca Annis (as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth) perform with sincerity, but the work as a whole lacks great purpose, except to establish the potential of human beings to do terrible things to one another. Orson Welles, Polanski’s “idol,” in his 1948 version, makes the play a study in despotism, in the psychology and mechanics, and ultimate irrationality, of a tyranny.

In the Tynan-Polanski modernist (or perhaps already “post-modernist”) version, no one is innocent, Macbeth is simply one assassin among many. The difficulty is, if everyone acts horribly, then no one does.

Polanski’s next major film was Chinatown. Released in June 1974 (at a volatile time, only weeks before the resignation of President Richard Nixon as a result of the Watergate scandal), the film is perhaps his most complete achievement to date. It is a remarkable work, both accessible to a wide audience and artistically and politically complex.

Set in 1937, Chinatown is loosely inspired by the so-called “California Water Wars” of the 1910s and 1920s. Los Angeles officials at the time, led by the Department of Water and Power’s superintendent, William Mulholland, conspired to divert water to the metropolitan area at the expense of farmers in the Owens Valley. The water was used to irrigate the San Fernando Valley, large parcels of which had secretly been bought up by a syndicate. The investors reaped a fortune.

Polanski’s film centers on private detective J. J. Gittes (Jack Nicholson), who is apparently hired by the wife of the water and power department chief engineer, Hollis Mulwray, to look into her husband’s infidelity. Gittes and his associates spy on Mulwray meeting his supposed youthful mistress at their “love nest.” In reality, the woman who retained the detective was not Mulwray’s wife, and Gittes has become a pawn in an effort to discredit the chief engineer, who has learned of the effort to divert water and other corrupt goings-on, and plans to expose them.

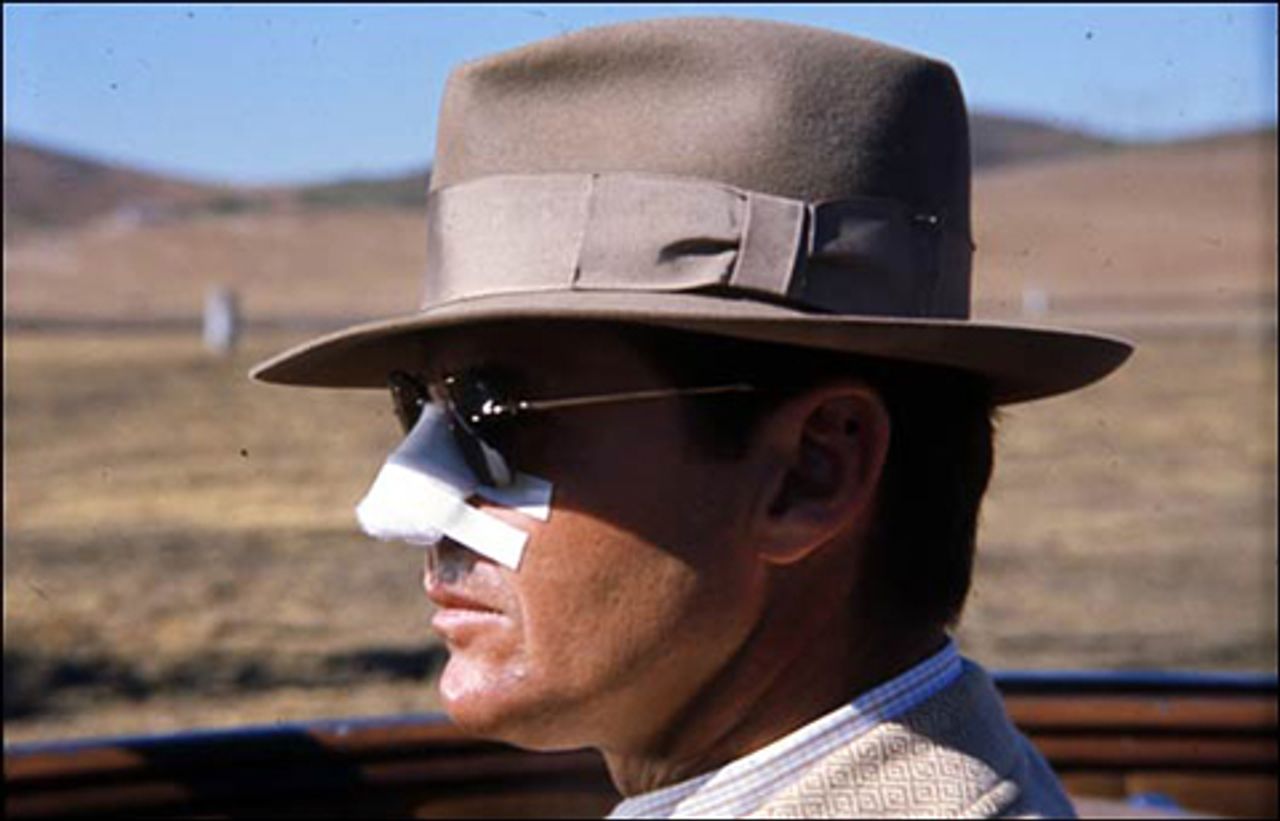

Polanski in a cameo role in Chinatown

Polanski in a cameo role in Chinatown

After Mulwray is murdered, his real wife, now a widow, Evelyn (Faye Dunaway), hires Gittes to investigate the crime. Gittes looks deeper into the water issue, getting his nostril sliced open in the process (thanks to a knife-wielding “midget” thug played by Polanski). He presses the fragile and neurotic Evelyn, “I think you’re hiding something.” She tries to put him off. As to her personal life, she says falteringly, “I don’t see anyone for very long … It’s difficult for me.”

Meanwhile, her sinister father, Noah Cross (John Huston), a wealthy businessman and Mulwray’s former partner, offers Gittes even more money, $10,000, to find Mulwray’s “girl-friend.” At their lunchtime meeting, Cross tells Gittes, “You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but, believe me, you don’t.”

In fact, “large-scale capitalist interests [are] arrayed against the people of Los Angeles and the small farmers of the nearby Valley,” who are all “coerced and duped” so that Cross can become “even wealthier than he already is.” (Herbert J. Eagle, “Power and the Visual Semantics of Polanski’s Films,” in The Cinema of Roman Polanski: Dark Spaces of the World)

Chinatown

ChinatownEvents unfold. Gittes’s efforts to protect Evelyn and the other young woman only end up leading to a tragic denouement.

Chinatown evokes with great effectiveness the world first depicted in the “hardboiled” novels of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and James M. Cain, among others. Polanski explained to Interview magazine that he was “trying to create … this Philip Marlowe atmosphere [Chandler’s private detective], which I had never seen in the movies the way I got it in the books.”

At their best, what those novels captured—and Polanski and screenwriter Robert Towne succeed in this as well—was the shocking contrast between the glamorous surface of life in southern California in the 1930s—the lush vegetation, ocean, sunny skies, movie stars, creamy stucco houses, sleek cars—and the rotten, money-grubbing reality at the heart of its cancerous economic growth.

The genial, avuncular Cross is guilty of everything. Toward the end, he tells Gittes, “Most people never have to face the fact that at the right time and the right place, they’re capable of anything.” The private eye has earlier challenged Cross about his plans to make additional piles of money: “Why are you doing it? How much better can you eat? What could you buy that you can’t already afford?”

A critic describes Cross in Chinatown as the “very incarnation of the political conspiracy in a single figure of voracious will.” What has already happened “can only get worse” because the businessman-developer “indicates that his goal is to buy up the future: the increasing voraciousness of Capital has no limit.” (Dana Polan, “Chinatown: Politics as Perspective, Perspective as Politics”)

The exile from “communism,” Polanski, but an honest artist, with his eyes open, made a meticulously constructed, devastating, and deeply-felt indictment of American society. One wonders if the political establishment, especially in Los Angeles, ever truly forgave him.

Polanski and Towne created Chinatown on the crest of a wave of radicalism that was sweeping the globe. The former considered Chinatown an “important and serious” work, he told an interviewer years later. (Although he noted in another published conversation shortly after the movie’s release that it was his most formally conventional work.) The director described his approach as being that of “an invisible witness to the events,” with the camera following. He went on: “If you have a story to tell, try to tell it in a simple, or maybe, elegant manner, and care about the emotions it can evoke in those kind enough to watch it.”

Speaking of Chinatown’s tragic ending, he observed, “If you want to feel for Evelyn, if you … feel in general that there is a lot of injustice in our world, you want to have people leaving the cinema with a feeling that they should do something about it in their lives.” Or, as he explained in his autobiography, he wanted audience members to get out of their seats “with a sense of outrage.”

The director, of course, had the benefit of the participation of Jack Nicholson at the height of his acting powers (Dunaway, Huston and the entire cast are also excellent). There is little question that Nicholson in the 1970s was one of the finest performers working in films. In, among others, Easy Rider (1969), Five Easy Pieces, The Last Detail, The Passenger, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Shining and Reds (1981), as well as Chinatown, he stood out.

His Jake Gittes can be taken as representative: here Nicholson personifies a certain lower middle-class American type, somewhat vulgar, but honest and quite forceful, skeptical yet not cynical, still naïve and occasionally a little wide-eyed, not too impressed with himself, a bully perhaps in some circumstances but essentially good-hearted, someone you would want on your side, someone capable of an enormous effort to get at the truth.

Polanski directed two more films in the 1970s, The Tenant (1976) and Tess (1979), both serious, if flawed, efforts.

The Tenant

The TenantThe former (from a novel published in 1964 by Roland Topor, a French artist of Polish-Jewish descent) is his most “Kafkaesque,” if that overworked phrase has much left in it by this time. Polanski plays a mild-mannered clerk, a Polish immigrant living in Paris, who rents an apartment that previously belonged to a woman, an Egyptologist named Simone Choule, who threw herself out of the window. He visits her in the hospital, where, wrapped head to toe in bandages like a mummy, she emits a terrible scream.

Trelkovsky moves into the unappealing flat (everyone tells him “it is difficult to find a good apartment” in Paris), but immediately comes up against the intolerance and repressiveness of the building’s owner, its concierge, and the majority of his neighbors. He’s not allowed to have female visitors, he mustn’t make noise, every move he makes is watched and disapproved of …

The mental torment generated by his inhospitable surroundings and his loneliness eventually drives him mad. He begins to hallucinate, he starts to dress up in the previous tenant’s clothes, in the end, he loses his identity entirely and becomes Simone, even imitating her method of suicide.

As Polanski later admitted, the lead character’s transition is rather abrupt and not entirely convincing. The Tenant (humanity as a whole perhaps, with its rather tenuous, continually threatened status on this planet) is at its best when it is most concrete about Trelkovsky’s difficulties: a nasty landlord, nosy and bigoted neighbors, a police official hostile to foreigners.

Polanski is charming in those portions of the film, as the much put upon, endlessly patient “little man,” who shrugs at setbacks, lets abuses roll off him like water off a duck’s back, while somehow maintaining his dignity. French actress Isabelle Adjani, as a friend of the former tenant who seems ready to help him stay or get back on his feet, is also a delight (Adjani is nearly unrecognizable in the role, which is unlike the enigmatic or self-pitying persona she played in a number of films).

The Tenant collapses under the weight of its own amorphous ambitions, but not before it has demonstrated the “‘terrible uncertainty of one’s own existence,’ as Kafka once put it, that is so often central to the haunting aspect of the director’s work.” (“Polanski and the Horror from Within,” Tony McKibbin) In the film, argues Ewa Mazierska (in Roman Polanski: The Cinema of a Cultural Traveller), Polanski “draws attention to the social context of the emergence of schizophrenia.”

Tess was Polanski’s second adaptation of a classic of English literature (Thomas Hardy’s 1891 Tess of the d’Urbervilles) and his first film after pleading guilty to unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor and fleeing the US in 1978.

Tess

TessNastassja Kinski starred as the young farm girl who undergoes a series of tests that eventually drive her over the brink. When her impoverished, broken-down father, John Durbeyfield, learns of his descent from an ancient noble family, Tess is sent to make a connection with a wealthy branch of the D’Urberville family that lives nearby. As a matter of fact, the family has purchased the name and coat of arms.

Alec D’Urberville attempts to seduce his lovely “cousin,” and when gifts and sweet words fall short, he rapes her. She leaves, eventually giving birth to a sickly baby that soon dies. She goes to work as a milkmaid and falls in love with the charismatic, reform-minded Angel Clare. They marry, but when she tells him of her past, he finds it difficult to accept, and abandons her. Tess is forced to turn to Alec to help her family avoid starvation. When a remorseful Angel returns for her and finds her living with Alec, tragedy ensues.

Polanski has again done a thorough and convincing job. Hardy’s novel is a heartbreaking story of class and sexual oppression. A good deal of that comes through in Tess, in its most affecting parts. Peter Firth is especially good as the high-minded, but repressed and hypocritical Angel Clare, who destroys his own and Tess’s chance for happiness with his “idealism” and stupid male egoism.

The director told interviewer Max Tessier in 1979, “Tess’s rebellion is often seen as something that occurs only at the end of the novel, but it’s actually present all the way through. Everyone has a place within society, and rebelling against it brings grave consequences. When Tess does rebel, it kills her.”

Unhappily, this element is not really worked through dramatically in the film. Kinski is fine when called upon to convey a smoldering resentment, but lacks the overall depth and dynamism required by the “unspoken rebellion” to which Polanski refers.

The falling off in Polanski’s work in the 1980s and 1990s was part of a general falling off. He directed only two films in the former decade, the sporadically amusing Pirates, with Walter Matthau, which failed badly at the box office, and the competent thriller, Frantic, with Harrison Ford and a young French actress, Emmanuelle Seigner, whom Polanski eventually married (they have two children). Bitter Moon, released in 1992, an “erotic melodrama,” is a poor, unconvincing film.

Polanski’s adaptation of Ariel Dorfman’s painful Death and the Maiden came out in 1994. The playwright was cultural advisor to the Allende “Popular Unity” regime in Chile, overthrown by a CIA-organized military coup in 1973. In his play, a woman in an unnamed South American country believes a man she accidentally encounters to be her chief torturer years before, who repeatedly raped her to the music of Schubert.

Dorfman, who has signed the petition calling for Polanski’s release from Swiss prison, explained at the time why he chose the Polish-French filmmaker to direct his work: “There were six or seven directors who wanted to make the film, but I felt Roman was the right person. He identified, as you say, with all three characters for his own biographical reasons; he has lived these situations of repression over and over again in his life. And therefore I had nothing to explain to him. I knew that in Polanski I had a director who would understand what the story was about without me having to explain it.”

Around that same time, Polanski expressed his dismay about the state of contemporary movie-making in an interview: “It’s already getting more and more difficult to make an ambitious and original film. There are less and less independent producers or independent companies and an increasing number of corporations who are more interested in balance sheets than in artistic achievement. They want to make a killing each time they produce a film.”

Unhappily, his own The Ninth Gate (1999), with Johnny Depp and Seigner, is something of a confirmation of the very syndrome he describes. It is a rather bland and anti-climactic, if visually striking, horror film, once again with satanic overtones.

In The Pianist, released in 2002, Polanski for the first time addressed himself directly to the terrible fate of the Polish Jews under the Nazis. The director based himself on the memoirs of Wladyslaw Szpilman (in an adaptation by Ronald Harwood)—a pianist and composer who miraculously survived German-occupied Poland and lived another five decades after the war—as well as his own experiences. The result is a difficult to watch, but restrained and dignified account of a population’s descent into hell, and an individual’s eventual re-emergence.

The Pianist

The PianistThe first part of the film deals with the step-by-step brutalization of Warsaw’s Jews in the first years of the German occupation. Szpilman’s family attempts to carry on under the increasingly humiliating and dangerous conditions. After two years, deportation orders come for the family. As they walk to the railway cars that will transport them to their deaths, a Jewish policeman, a collaborator with the Germans, recognizes Wladyslaw and permits him to escape—an episode with marked similarities to Polanski’s own getaway in Krakow.

Then comes Szpilman’s two-and-a-half year struggle to survive, both inside and outside the Warsaw Ghetto. From an apartment just beyond it, he watches the heroic Ghetto uprising of April 1943 and later witnesses the general Warsaw uprising in August 1944. In the last period of the war, a German officer discovers him in an abandoned building, hears him play the piano, and helps keep him alive.

In its review in 2002, the WSWS noted a number of weaknesses in the film, observing that “there is something misleadingly passive and empty about Szpilman on screen,” and that Polanski, for his own ideological reasons, had softened “some social and political elements in the memoir,” including Szpilman’s contact with a socialist oppositionist inside the Warsaw Ghetto.

Nonetheless, the WSWS described the film as “a moving evocation of the Nazi Holocaust, depicted through the experience of a single survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto. Polanski does not break new ground, but tackles the subject with intelligence and dignity. He has been largely successful in bringing to the screen the impressive memoir of Wladyslaw Szpilman.”

The film was well-received and generally viewed as an artistic “return to form,” gaining Polanski the Best Director award at the 2003 Academy Award ceremony, accepted for him by Harrison Ford.

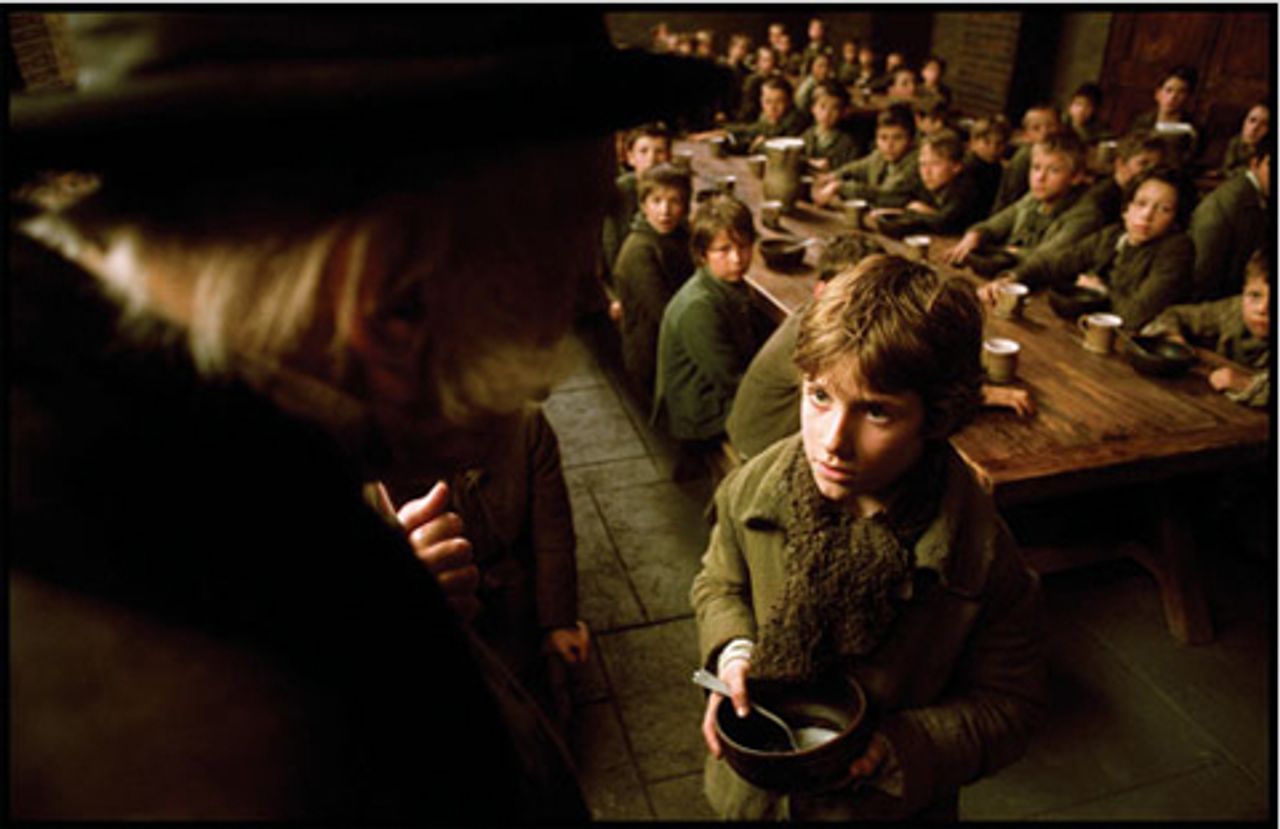

On the strength of that success, Polanski turned to another English classic, Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (2005, also from an adaptation by Harwood), in part, he explained, so that his own children could watch one of his films.

Oliver Twist

Oliver TwistPolanski’s version is a straightforward and compelling recounting of the story of the famous orphan boy in early Victorian England. In the Polanski rendering Oliver (Barney Clark) escapes abuse at the hands of his master coffin maker’s wife and senior assistant by running away on foot to London. There, he falls in with a gang of boy pickpockets, led by the Artful Dodger (Harry Eden) and managed by Fagin (Ben Kingsley).

Falsely accused of stealing a handkerchief, Oliver is brought before a sadistic magistrate, eager to hand down a harsh sentence. Proven innocent, his supposed victim, the kindly and affluent Mr. Brownlow (Edward Hardwicke) takes Oliver to his mansion and proposes to raise him.

Fearful that the boy will finger them to the authorities, Fagin and his brutish associate, Bill Sikes (Jamie Foreman), conspire to kidnap Oliver, with the help of Bill’s girl-friend, the young prostitute Nancy (Leanne Rowe). With Oliver under lock and key at Fagin’s hangout, and following a failed break-in at Mr. Brownlow’s house, Nancy takes pity on Oliver and attempts to organize his rescue. Bill finds out about her betrayal and beats her to death. In a climactic scene, at Fagin’s, the police close in on Bill, who comes to a pitiful end. Oliver, in the film’s epilogue, pays a visit to Fagin awaiting execution in prison.

His version of the Dickens novel brings out themes and motifs close to Polanski’s heart: the abandoned child, alone in strange and unforgiving surroundings; the bewildering, apparently arbitrary cruelty of the authorities; the general persecution of the weak and defenseless; and, as well, a confidence, which sometimes flickers very low, in the essential goodness (and immense resilience) of human beings. Kingsley, who on occasion strikes the spectator in all his precision as mannered and lacking in spontaneity, delivers a moving performance as the avaricious, grotesque, but still oddly sympathetic fence.

All in all, this is a film career worthy of serious attention. One might learn something important about our world and our times by watching Polanski’s films. He has done honest and artistic work, given characters and events “a definite dramatic and visual shape,” in a difficult and often regressive cultural climate.

And now … Polanski, at the age of 76, has been arrested by Swiss authorities who intend to hand him over to US officials, who would like to lock him up. Given his life history, it seems fairly safe to assume that whatever emotions are washing over the filmmaker, astonishment is not among them. But this travesty of justice, accompanied by all manner of pious and self-righteous bleatings, should also evoke outrage.

Polanski once told an interviewer: “One of the profound experiences of my youth was seeing Of Mice and Men [1939]. That has stayed with me. I couldn’t stop thinking about this big, lovely man and his friend, and their friendship, and I thought that if I were ever a film maker, I would certainly try to do something along those lines, something against injustice and intolerance and prejudice and superstition. And I have. These elements are weaved through my films.”

It’s true, and he should be allowed to keep doing “something along those lines,” which is no small contribution to his fellow human beings.

* * *

Filmography:

Oliver Twist (2005)

The Pianist (2002)

The Ninth Gate (1999)

Death and the Maiden (1994)

Bitter Moon (1992)

em>Frantic (1988)

Pirates (1986)

Tess (1979)

The Tenant (1976)

Chinatown (1974)

Che? [What?] (1972)

Macbeth (1971)

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Dance of the Vampires (1967) or The Fearless Vampire Killers (USA)

Cul-de-Sac (1966)

Repulsion (1965)

Knife in the Water (1962)

Short films:

Mammals (1962)

The Fat and the Lean (1961)

When Angels Fall (1959)

The Lamp (1959)

Two Men and a Wardrobe (1958)

Let’s Break Up the Dance (1957)

A Toothful Smile (1957)

Murder (1957)

Concluded