This is the fifth of a series of articles devoted to the recent Toronto film festival (September 10-19).

“All honour and reverence to the divine beauty of form! Let us cultivate it to the utmost in men, women, and children in our gardens and in our houses. But let us love that other beauty too, which lies in no secret of proportion, but in the secret of deep human sympathy.… [L]et us always have men ready to give the loving pains of a life to the faithful representing of commonplace things.” —George Eliot

The poor throughout the world are neglected and abandoned, increasingly left by the authorities to their own devices to cope (or not) with their difficulties. In an imaginative and sensitive fashion, some artists are beginning to concern themselves with this state of affairs. Several of the films at the Toronto festival exemplified this development in different ways and in different locales.

In a number of cases, the sincerity and compassion of the filmmakers make themselves powerfully felt in the works. In the best cases, there is a clear-eyed and determined investigation into social life involving people, who, as Eliot puts it, “have no picturesque sentimental wretchedness,” but instead suffer painful physical circumstances with attendant psychological scars.

That filmmakers maintain a level of commitment and devotion to their subjects is of significance. Yet, despite the worthiest of intentions, there continues to be a large measure of passivity that can’t simply be chalked up to the weakness of the individual artist. Along with passivity, there is a tendency to limit the scope of the subject matter, to tackle big issues with a narrow perspective, which expresses a certain impasse. Even in the best of films, this befuddlement in the face of vast problems is ingrained in the dramatic fabric. This shortcoming will be overcome when the oppressed are seen less as victims and more objectively, and accurately, as the lever of change.

A number of films were noteworthy for their humaneness. From Britain comes a movie that deals with a strained child services system, while another from South Africa centers on a mother’s solitary battle to handle her son’s severe disability. The outskirts of Rome provides the setting for a story about circus folk in a trailer park who take responsibility for an abandoned child.

The Unloved

The UnlovedThe Unloved is acclaimed British actress Samantha Morton’s directorial debut. It was inspired by Morton’s own childhood as a ward of the state until she reached the age of 18. The movie’s protagonist is 11-year-old Lucy (Molly Windsor) who has been in and out of foster care. She is placed in a childcare home after a beating from her biological father (Robert Carlyle), who is neither financially nor psychologically fit to raise her, despite their affection for one another. Lucy joins other children in a facility where the staff are overwhelmed and underfunded. In one case, a staff member takes advantage of an inmate’s loneliness and need for affection.

Lucy rooms with the tough, much-sinned-against Lauren (movingly performed by Lauren Socha), who seems to be on her way to a life of prostitution. The latter girl, a 16-year-old, is painful to watch and exemplifies the innate sweetness and vulnerability of “the unloved”—and the enormous level of trauma they absorb. Morton dramatizes the relationship between her central characters with an honest and complex emotionalism.

During a question-and-answer session at the festival, Morton—all heart—expressed forthrightly her belief that people “are really good” and struggle mightily against adverse circumstances not of their own making.

Shirley Adams

Shirley AdamsIn Shirley Adams, first-time director Oliver Hermanus shows how working class people face a backbreaking challenge to survive. In Cape Town, 10 months after her son was shot and paralyzed, Shirley Adams (Denise Newman—one of South Africa’s leading stage actresses) was deserted by her husband (he continues to leave money in the mailbox). Shirley now shoulders the emotional load in caring for her son Donovan (Keenan Arrison), whose debilitating condition has made him suicidal. His injury was the result of a stray bullet in a gang shooting. The shooter turns out to be a horrible surprise.

The family’s meager assets have been depleted paying medical bills. With no money or job, Shirley is physically and mentally drained. Getting through the day is exhausting. Keeping her son alive is a nightmare as his mental state deteriorates. The only solutions that present themselves are tragic ones. A young woman from the hospital attempts to help, but her presence almost seems to do more harm than good.

At the end of the film’s screening in Toronto, director Hermanus spoke about Cape Town districts where “poor kids are frustrated; where there is no education or outlets for them. As a result, they either become gangsters or filmmakers.” The film is honestly and sincerely written and directed.

La Pivellina

La PivellinaCircus performers eke out an existence in the film La Pivellina, by the Italian-Austrian filmmaking team of Tizza Covi and Rainer Frimmel. The entertainers are skilled, yet audience members are scarce at the circus’s muddy encampment near Rome. There is, however, a deep solidarity among the outcasts who live, together with their animals, communally.

At the film’s opening, Patti (Patrizia Gerardi), in her 50s, with flaming-red hair, finds an abandoned toddler in a park with a note from the child’s mother saying, “will come back to pick her up.” Patti, her husband (Walter Saabel), and 13-year-old neighbor (Tairo Caroli) embrace the new addition to their improvised family. All the characters in the film are endearing and possessed of a generosity that contrasts with the harshness of their conditions.

These are all compassionate efforts. And, yes, “things may be lovable that are not altogether handsome” (Eliot). Human feeling “does not wait for beauty—it flows with resistless force and brings beauty with it.”

Artists and others

Remarkable artistic and spiritual figures were dealt with in a number films. Despite the serious research carried out into the lives of the various personalities, the films, set in diverse eras, had a certain sameness in the way the material was approached, regardless of whether the works were fiction or documentary in format.

Movies in which historical context was a crucial element, such as Vision, about a twelfth-century composer, philosopher and naturalist—and female—and I, Don Giovanni, concerned with Mozart’s librettist, exhibited many of the same problems as those set in modern times, like Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould. Although genuine efforts were made to embed the narrative in history, the filmmakers did not probe thoughtfully enough the socio-historical conditions that produced these geniuses.

The “one damn thing after another” view of history yields limited insights and therefore produces works that are ultimately unsatisfying.

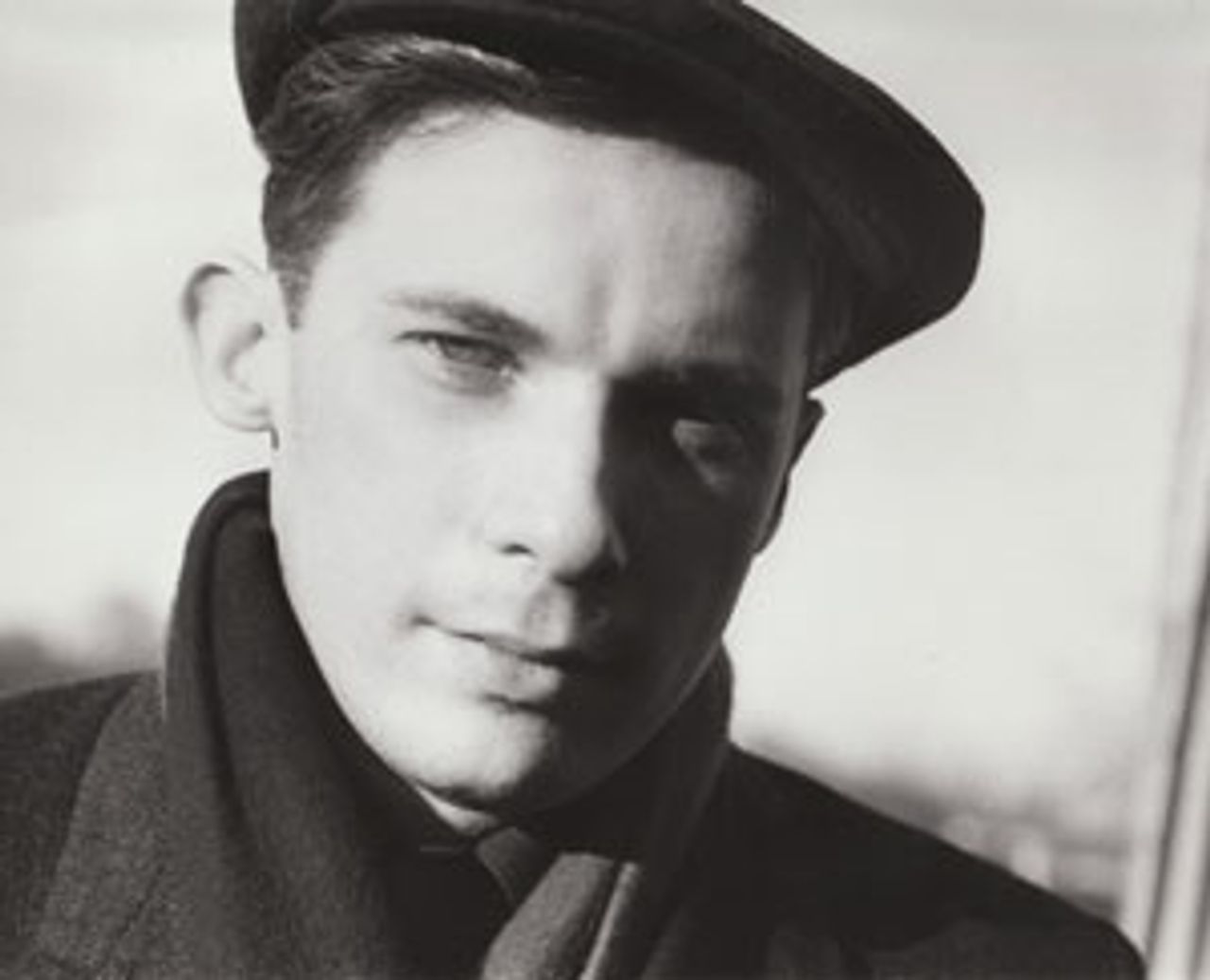

Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould

Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn GouldGenius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould by Canadian documentarians Michéle Hozer and Peter Raymont is a compilation of previously unseen footage of Gould, as well as hundreds of photographs and excerpts of private home and studio recordings. The film’s main talking heads include Cornelia Foss (painter and wife of Lukas Foss, the prominent composer, pianist and conductor); Roxolana Roslak, the Hungarian soprano; pop-singer Petula Clark; and Vladimir Ashkenazy, the Russian conductor and pianist, to name a few.

Gould (1932-1982), one of the great pianists of the twentieth century, was highly eccentric and reclusive. The documentary traces his life and career, whose highlights include the history-making eight-concert tour in Moscow and Leningrad in 1957, in which Gould performed Bach—a composer seen as too connected to religion by the philistine Stalinist bureaucracy—to a wildly enthusiastic public. A photograph of Gould and the Soviet pianist SviatoslavRichter records the meeting of two supreme musicians.

Another seminal event treated in the film is the 1962 New York Philharmonic concert, viewed as one of the orchestra’s most controversial. Remarks made by conductor Leonard Bernstein in introducing Gould are famous: “Don’t be frightened. Mr. Gould is here.... You are about to hear a rather, shall I say, unorthodox performance of the Brahms D Minor Concerto, a performance distinctly different from any I’ve ever heard, or dreamt of for that matter.... But the age-old question still remains: ‘In a concerto, who is the boss, the soloist or the conductor?’... [W]e can all learn something from this extraordinary artist, who is a thinking performer.”

Gould’s five-year affair with Cornelia Foss, which only recently became public (her husband died earlier this year), is one of the film’s preoccupations. Foss speaks fondly of Gould—as do her children. Gould was an admirer of her husband’s musicianship. The families of both Cornelia and Lukas had fled Nazi Germany.

Genius Within takes up Gould’s decision to quit public performance for the recording studio in 1964 more or less at the height of his career. Emotional factors aside, the Toronto-born pianist saw the relationship of a concert performer to the audience as akin to that of a bullfighter to his spectators. The metaphor was not meant approvingly. He felt that recording was a more democratic, do-it-yourself technology, a sentiment ahead of its time.

Says Cornelia Foss: “Anything pretentious made him ill,” and the desire to shun celebrity entered into his decision to quit the stage. The relationship between Foss and Gould ended as the latter descended into paranoia and abuse of prescription medication. Recalling Gould as a “Renaissance Man,” the film asks but never answers the question: What in the Gould mystique continues to captivate beyond the genius of his music?

Genius Within refers in vague terms to the 1960s and raises interesting questions about a man who took his art seriously—to a crippling degree. But more could have been done to connect, in a complex fashion, the artist’s contrarian streak with the upheavals and traumas of the times.

Vision

VisionVision from German filmmaker Margarethe Von Trotta (Rosa Luxemburg, Rosenstrasse) chronicles the extraordinary story of Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), composer, scientist, doctor, writer, poet, philosopher, and ecologist.

Raised in a Benedictine monastery from the time she was eight, Hildegard is the first composer (of either gender) whose biographical details are known, and the first woman to write about human sexuality. Interested in all aspects of nature, and convinced of its healing powers, she wrote insightfully about the physical-natural world around her. Her independence and relentlessness made her a thorn in the side of the Church hierarchy. According to the filmmakers, somewhat sweepingly, Hildegard was responsible “for bringing Europe out of the darkness and into modern era of science and enlightenment.” Dante and Leonardo da Vinci, among others, were later influenced by her work.

Von Trotta’s film is competently made, with impressive lighting and design. The talented actress, Barbara Sukowa (Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz), who has now made five movies with Von Trotta, plays Hildegard, carrying much of the weight. Always intelligent, Von Trotta’s films are rarely inspired, and Vision is no exception. But she is conscientious in her recreation of Hildegard’s world and some of its conflicts. The movie rings true. However, too much effort is spent in impressing the spectator with the protagonist’s list of accomplishments, rather than exploring the actual content of her ideas and her times.

I, Don Giovanni

I, Don GiovanniI, Don Giovanni by veteran Spanish director Carlos Saura (The Hunt, Carmen, Tango, Goya in Bordeaux) focuses on librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte (Lorenzo Balducci), who penned the librettos for some of Mozart’s greatest operas, including Così fan tutte, Marriage of Figaro and, as the film’s title indicates, Don Giovanni.

A fascinating and brilliant figure, Da Ponte (1749-1838) was forced to convert from Judaism to Christianity in 1763 for the sake of marrying well. He was trained as a priest, took a mistress, fathered a child, and opened a brothel, which led to his banishment from Venice. In Vienna, the opera-loving emperor paired him with Mozart (Lino Guanciale), and at that point, according to Saura’s film, Da Ponte became inspired by the amorous exploits of Giácomo Casanova (Tobias Moretti).

Da Ponte eventually emigrated (or, rather, fled from his creditors) to the United States and died in New York City.

The film is colorful and lively. Unfortunately, it is too much of a tabloid-like, sensationalist accounting of Da Ponte’s life, and makes both Mozart and his librettist appear simply as dissolute rogues. If it weren’t for the film’s soundtrack—provided by Don Giovanni—one might be inclined to forget the stature and achievements of both Da Ponte and Mozart.

Italy in the 1970s

La Prima Linea (The Front Line) by Italian filmmaker Renato De Maria is based on the memoirs of a founder of an Italian terrorist group affiliated to the Red Brigades. The “Front Line” carried out robberies and targeted assassinations in Italy in the 1970s and early 1980s.

The film is well made and treats with some sympathy the decision of a young person to embark on such an extreme course under the conditions of the time. This has led to its coming under attack by the Italian right and bourgeois media. De Maria’s work also shows how little political understanding the group members had and the dead end in which they found themselves, leading to their futile and reactionary actions. Unfortunately, the film never refers to the political forces primarily responsible for the disorientation and despair of the Front Line members, above all, the Italian Communist Party.

To be continued