The death of celebrated script-writer Suso Cecchi d’Amico, aged 96, in Rome on July 31, signalled the passing of one the few remaining veterans of what is often described as the golden age of Italian cinema—the period that began in 1943 with the collapse of Mussolini’s fascist regime, and lasted until the early 1960s.

The talented d’Amico wrote over 110 scripts during her extraordinary six-decade career, including several that were turned into genuine movie masterpieces. She won Italian cinema’s Silver Ribbon nine times for best screenplay and was awarded a Golden Lion lifetime achievement award at the Venice film festival in 1994.

Giovanna or “Suso” Cecchi was born in 1914 to an upper-middle class Tuscan family and raised in a highly cultured environment. Her father, Emilio Cecchi, was an author and leading literary critic; her mother, the painter Leonetta Pieraccini, was from a well-known theatrical family.

Suso Cecchi d'Amico

Suso Cecchi d'AmicoSuso studied in Switzerland and England and was exposed to cinema at an early age when her father became head of Cines, one of the country’s major film producers, in the 1930s. Fluent in French and English, she worked for eight years as a translator for the Italian ministry of industry, and in 1938 married Fedele d’Amico, editor of an underground newspaper and a member of the Christian Left faction of the anti-fascist resistance. He later became one of Italy’s leading musicologists.

Suso d’Amico collaborated with her father in translations of Shakespeare and Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, and in the mid-1940s translated several foreign-language plays staged by Luchino Visconti, including works by Jean-Paul Sartre, Marcel Achard, Jean Cocteau, Jean Anouilh, as well as Ernest Hemingway’s The Fifth Column, about the Spanish Civil war.

D’Amico began writing screenplays in 1946. Her first credit was for Renato Castellani’s My Son, the Professor, which was followed in 1947 by two films for Luigi Zampa—To Live in Peace, a tragicomedy about rural life during the German occupation of Italy, and the commercially successful Angelina: Member of Parliament, a comedy starring Anna Magnani.

Angelina: Member of Parliament

Angelina: Member of ParliamentD’Amico’s personal history and left-liberal outlook naturally enough drew her to the neo-realist movement. This led to her involvement in The Bicycle Thief (1948), Vittorio de Sica’s landmark movie about an unemployed working-class father and his seven-year-old son. Like many Italian films during this time, The Bicycle Thief was a collaborative effort and involved at least six credited writers, including neo-realist theoretician Cesare Zabattini.

D’Amico always downplayed her contribution to the film. The final scene of this seminal work, however, when the father attempts to steal a bicycle, much to the disbelief and shame of his son, was suggested by d’Amico, and is one of the most affecting moments in post-WWII cinema.

The Bicycle Thief

The Bicycle ThiefCommenting later on this period, she said: “For the films we did during neo-realism— or what they call neo-realism—we had no money so we just shot on the streets or in houses. We couldn’t afford actors and there weren’t many actors around because the standard of theatre was very poor. Besides, all the theatres were bombed. So, we just found people on the streets. You would meet a person who was right for the role and ask them to play it. That was it.

“It was only afterwards that someone else, somewhere else in the world, decided to call it ‘neo-realism’ and write many books about it. This was despite the fact that it was only a little group of friends who just wanted to make films and went out into the streets to do so. If we had as many newspapers and magazines back then as we do now, maybe many of us would have become journalists instead of making films. But there weren’t many papers and making film was inexpensive and we merely wanted to tell our stories about our experiences of that era.”

D’Amico also worked on de Sica’s Miracle in Milan (1951) about poverty and homelessness. The film was criticised, however, by some of the neo-realists who disliked its fantasy sequences and considered the ending “too sentimental”.

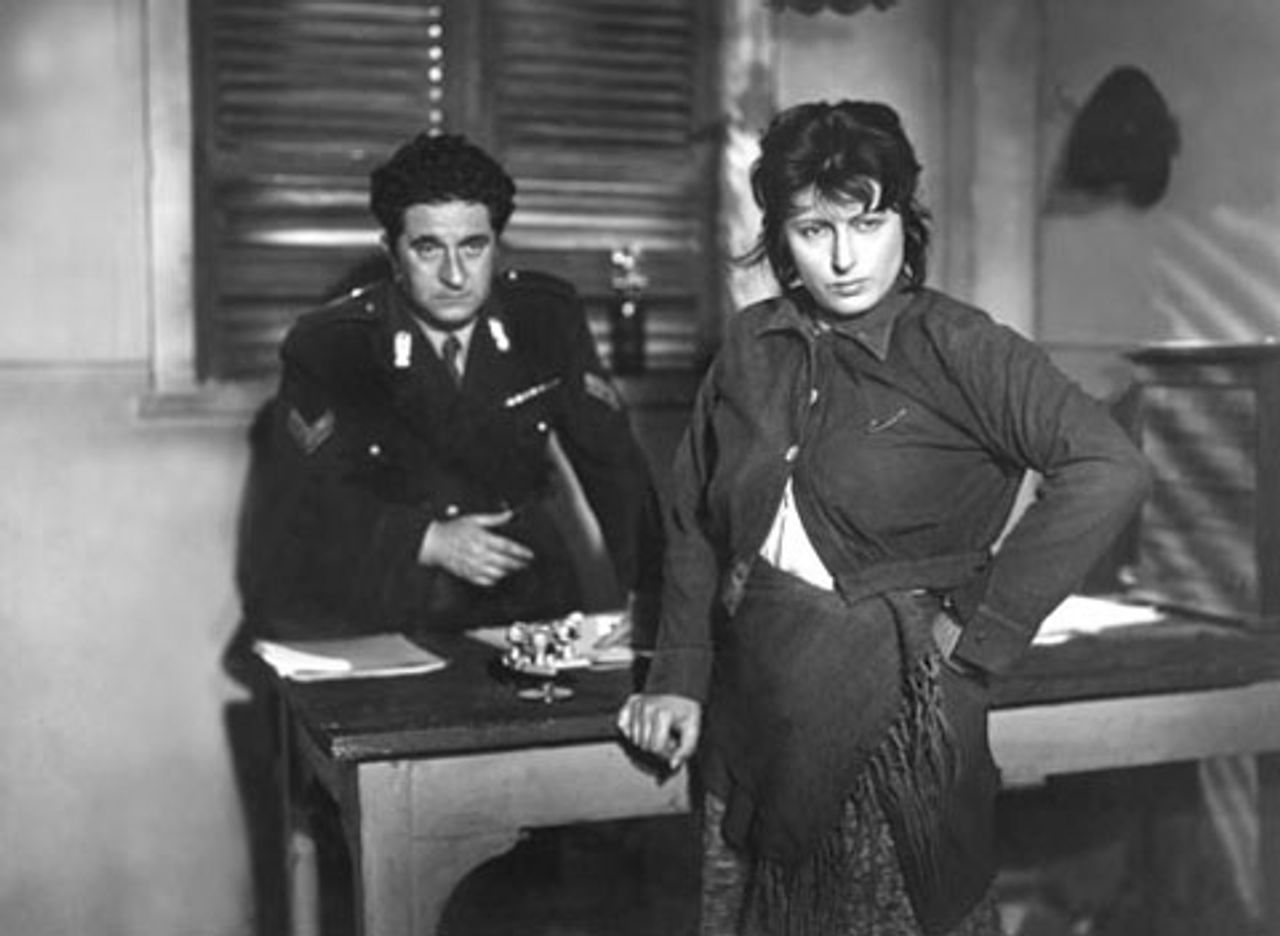

According to the neo-realist doctrine, filmmakers had to focus entirely on the lives of the oppressed. Not surprisingly, d’Amico and others soon began to strain against this and other proscriptive aesthetic constrictions, leading to an artistically fruitful and life-long film collaboration with Visconti. It began with Bellissima, the director’s satire on the Italian film industry and the desperate attempts of a working class mother (Anna Magnani) to find stardom and wealth for her daughter.

Senso

SensoLike Visconti, d’Amico’s sources of artistic inspiration were mainly literary—novelists such as Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust and Gustav Flaubert—and her next script for Visconti was the visually sumptuous and masterly Senso (1954). Based on Camillo Boito’s novella of the same name, the big-budget production represented a definitive break from the director’s neo-realist period. Set in 1866 Venice, inspired by the music of Verdi and filmed in colour, it featured 1,300 actors, 2,100 horsemen and 8,000 extras.

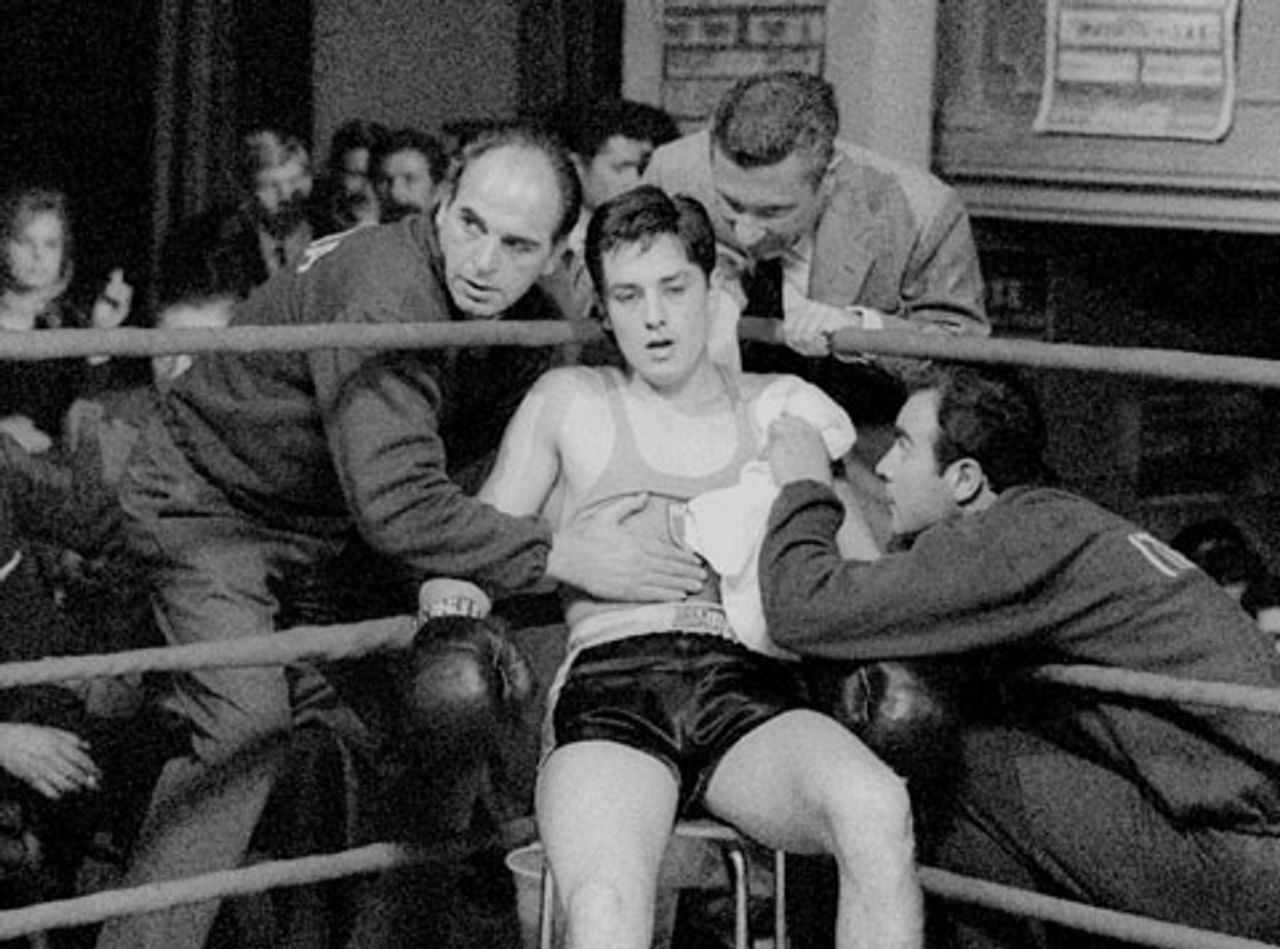

Next came d’Amico’s screenplays for Visconti’s White Nights (1957), adapted from a Dostoyevsky short story, and her favourite film, Rocco and His Brothers (1960), which one critic said “combined the realist squalor of the boxing racket with a dramatic sweep that would not have been out of place in Dostoevsky”. Nadia, a tragic prostitute in the movie, in fact, was directly based on a character from The Idiot.

Rocco and His Brothers

Rocco and His BrothersDuring this period, d’Amico also produced screenplays—melodramas, comedies and political crime stories—for all the leading Italian filmmakers: Michelangelo Antonioni (The Lady without Camellias [1953] and The Girlfriends [1955]), Luigi Comencini (The Window to Luna Park [1956]) Mario Monicelli (Big Deal on Madonna Street [1958] and The Passionate Thief [1960]) and Francesco Rosi (La sfida [1958], The Magliari [1959] and Salvatore Giuliano [1962]), among others.

Big Deal on Madonna Street

Big Deal on Madonna StreetIn 1963 d’Amico collaborated again with Visconti to produce a script of The Leopard, based on Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s famous novel. This was without doubt her most important screenplay. It brilliantly captures the end of the era of aristocratic privilege and the rise of the Italian bourgeoisie.

D’Amico suggested that the epilogue in Lampedusa’s novel be eliminated from the movie and convinced Visconti to conclude the film with a lengthy society ball scene in Palermo.

The Leopard

The LeopardThe key task of the movie’s final sequences, she later explained, was to “communicate a sense of death and decadence in dance through the rhythm of the film, without betraying the novel, and to show what Tancredi [the son of the Sicilian nobleman-aristocrat] and Angelica [the daughter of a local bourgeois] would become … The novel, after all, is the story of the first time that different social classes in Italy mix.”

Other work with Visconti followed: The Stranger (1967), Ludwig (1972), Conversation Piece (1974) and his last film, The Innocent (1976). Visconti and d’Amico planned to film Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, but the director’s death in 1976 prevented the project being realised.

D’Amico continued working almost up until her death, writing more than 30 scripts between 1976 and 2006, including one for Martin Scorsese’s My Voyage to Italy (1999), a useful and interesting overview of Italian cinema, and assisting in British director Derek Jarman’s production of Caravaggio (1986).

The disarmingly modest d’Amico never attempted to glorify her achievements or scriptwriting itself, insisting that it “was a craft, not an art”. She emphasised, however, that a screenwriter had to “write with his eyes” and, in later years, often criticised the general decline in screen culture.

Asked in 1999 whether serious, high-quality cinema was in danger, she bluntly replied: “Yes, because all we have now are mediocre films ... Unfortunately we are not living in a good time for cinema. The disaster is that films cost too much to produce. You become too careful and there are no more producers. It has become business, an industry.

“If I had thought that cinema was not art before, then now it has become an industry of bad taste, in part because television has dragged the level of intelligence down, down, down. We no longer need to use our brains and people are content with television.... [W]hat’s important [is] to make films for yourself and not to think about profits. If you are pleased with what you have done, that is enough.”

D’Amico brought an aesthetic intelligence, humanity and social consciousness to cinema that is largely absent from contemporary cinema. Speaking at her funeral in Rome, director Mario Monicelli told mourners that Suso Cecchi d’Amico was a key figure of her generation who, along with others, had helped to “show a new way of doing things, of producing ... Now that she’s gone I feel very much alone.”

The author also recommends:

San Francisco International Film Festival 2010 Part 6: Luchino Visconti’s Senso—drama and history

[3 June 2010]

I am Love and The Leopard: Italian cinema new and old

[27 July, 2010]