This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Volcker warns of danger in continuing dollar slide

Paul Volcker

Paul VolckerOn April 7, 1987, Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker warned of “substantial risks” in the continuing downslide of the dollar on the world currency markets. Volcker told a Senate banking subcommittee, “There are clear dangers in relying too much on exchange rates alone.” He called for reducing the need for foreign capital to finance the dollar by cutting its budget deficit. Talks were set to open in Washington between the US and its major trading partners the following day.

The bond market led the stock markets in a sharp decline as the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 44 points, largely as a result of pessimism over the upcoming talks. Of particular concern, according to Volcker, was the balance of trade deficit. He had called for the US to rely more on exports and less on imports, complaining that the country was consuming more than it was producing. This would be done first and foremost by decreasing living American living standards. Domestic spending would have to be curtailed, according to the Fed chief, whose 1979 interest rate “shock therapy” had devastated American industry and accelerated the economy’s financialization.

Volcker’s remarks were seen as an attempt to counter the pressure toward trade war expressed in the previous week’s US-imposed tariff on Japanese electronics products. He noted that “The trouble is higher dollar prices of imports as the dollar depreciates—the well-known J-curve effect—might offset improvement in of net exports for some time.” Volcker also noted the debt problems of developing nations and opposed “radical” solutions, such as writing off or forgiving those debts.

50 years ago: Another coup in Syria

Less than one week after a coup d'état overthrew Syria’s civilian government, a second military putsch took place against the first, resulting in yet another change of government.

Less than one week after a coup d'état overthrew Syria’s civilian government, a second military putsch took place against the first, resulting in yet another change of government.

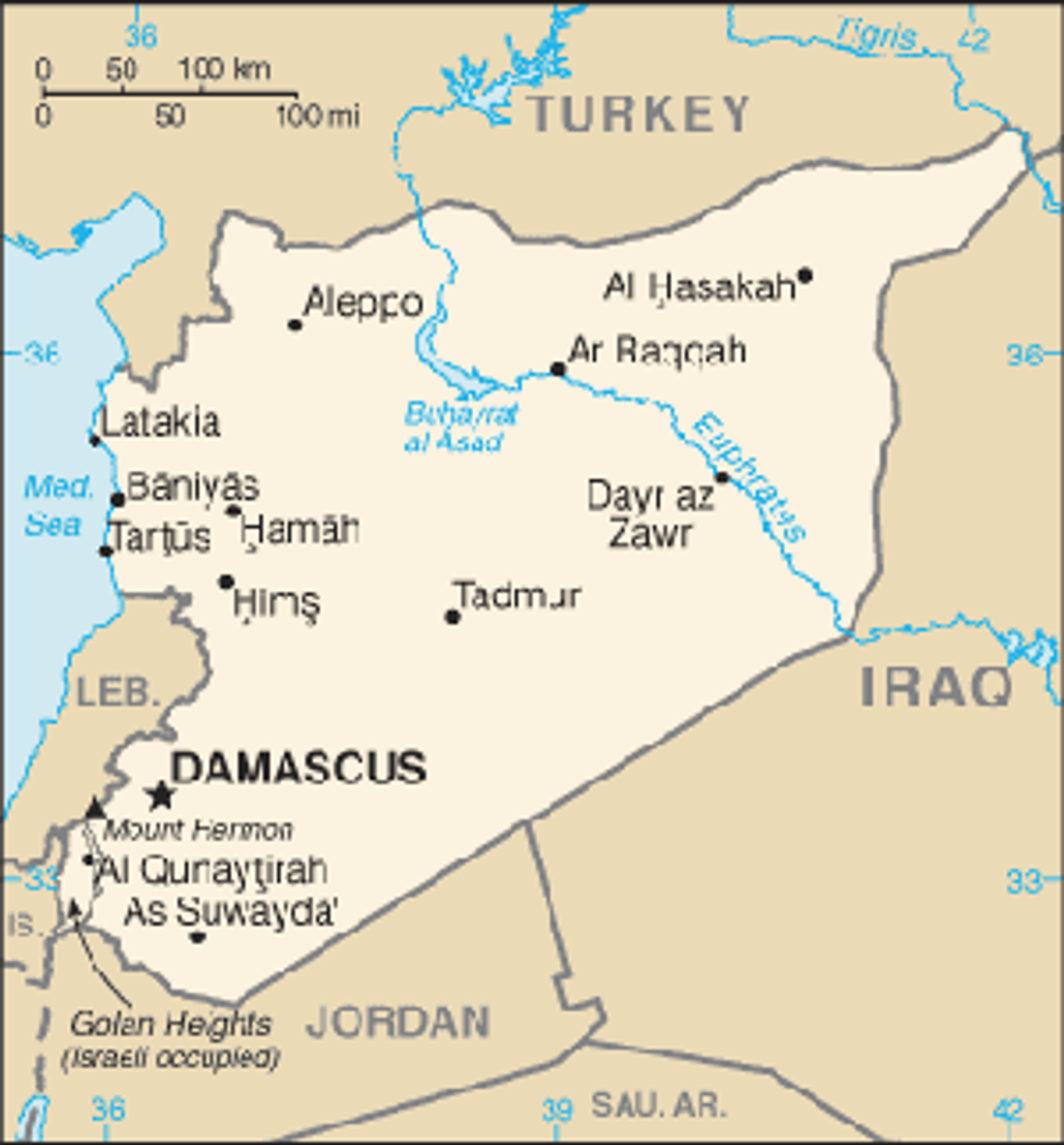

The new military revolt was described as being Nasserite. “Free officers” who launched the counter-coup in Aleppo ostensibly sought to revive the union with Egypt in the United Arab Republic, which had been ended by yet another coup months earlier, on September 28, 1961. By April 2, the second revolt had effectively gained control of much of Syria outside of Damascus, the capital.

On April 3, a truce was reached among the factions of Syria’s military at a conference in Homs. The leaders of the March 28 coup, who had also led the officers’ revolt against the UAR, were exiled from the country. The civilian president of Syria, Nazem el Kodsi, who had been ousted and jailed, was released and restored to power, as were all other arrested officials. Major General Abdel Karim Zahreddin, who had earlier backed the March 28 coup, was to remain as commander of the Syrian military. There were vague promises of a referendum over reunion with Egypt.

As was the case in each of Syria’s military coups, and indeed the 1957 union with Egypt, the military aimed to prevent revolution and confuse the working class. The March 28 coup’s proclamation of “Arab socialism” had failed to convince “workers, students, and peasants,” according to the New York Times, who held demonstrations across the nation in favor of the union with Egypt, including at Homs, Aleppo, Hama, and Baniyas. This seems to have triggered the second coup.

El Kodsi was a right-wing figure who during his first months in office moved to denationalize Syrian industry and restore land to landlords who had been expropriated under Nasser. He had also attempted to reorient Syria toward the US and away from the Soviet Union, but this goal had been undermined by tension with the primary US regional ally, Israel. Two weeks before the first coup, on March 16, Israel carried out a cross-border raid into Syria.

75 years ago: American workers continue sit-down strike wave

Worker sleeping in occupied Chevrolet plant

Worker sleeping in occupied Chevrolet plantA new sit-down strike shut down all nine Chevrolet plants in Michigan and Ohio on April 2, 1937. A day earlier, on April 1, a number of sit-down strikes had broken broke out in General Motors owned or controlled facilities, resulting in the closure of other production facilities relying on striking plants. The strikes were provoked by the management refusing to deal with United Automobile Workers (UAW) union in accordance with the agreement struck between the two parties in March. Chevrolet’s parent company, General Motors charged the UAW with failing to control the workforce, citing some 30 wildcat sit-down strikes by GM workers since the provisional agreement to end the first wave of Flint sit-down strikes on March 12.

Important negotiations were also under way between the UAW and Chrysler, where a March sit-down strike had pushed the city of Detroit to the verge of a general strike. “The discussion, as might have been expected, turned on the ability of the union to continue to control its members,” the London Times explained. “Mr. Chrysler is well supported in his view that any agreement with the union, may be useless, since it appears unable to force its own members to comply with an agreement already reached with another company.”

On April 4, when representatives of the Chrysler car corporation complained about the activities of socialists within the unions’ ranks, CIO head John L. Lewis pledged to “purge” those activists. On April 8, the two sides reached an agreement that established the UAW as the official union of its members, but not all Chrysler workers.

The sit-down strike wave continued. “Reports of such strikes, great and small, come from all parts of the country, and with them stories of violence,” according to the Times. In New England on April 3 jewelry workers began sit-down strikes in Rhode Island. On the same day in Lewiston, Maine police ordered the arrest of 20 strikers held responsible for strikes in shoe factories in Lewiston and Auburn. Also on April 3, Ford workers struck in Kansas City, Missouri.

100 years ago: San Diego police hand over IWW prisoners to vigilante mob

IWW free speech fight in San Diego

IWW free speech fight in San DiegoOn 5 April 1912, political prisoners from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were taken to the Sorrento Valley District, on the order of San Diego Police Chief Keno Wilson, and handed over to a crowd of vigilantes. The prisoners were branded, beaten, and shot at by the mob, who tried to force them to kiss the flag and sing the Star Spangled Banner [the national anthem], before forcing them out of the county. An unknown number who died were buried in unmarked graves.

The attack was part of ongoing political repression of the IWW, which was viewed as a threat by authorities because it opposed the narrow craft unionism of the AFL, and fought to unite all sections of the working class in “one big union” as part of an industrial and revolutionary struggle against the profit system. The IWW was at the forefront of a number of industrial and free speech struggles in the United States between 1909 and 1915.

Wilson’s order was in part motivated by the overcrowding of San Diego’s jails, which held hundreds of IWW prisoners at different times in 1912. At the end of February 1912, the IWW rejected San Diego city government’s offer to release IWW prisoners, who were held in jail on conspiracy charges and unable to afford bail.

The IWW campaigned against an ordinance passed by the San Diego City Council on 8 January 1912, which prohibited public speech within a six-block area. The organization was regularly attacked by vigilantes who were backed and incited by the police and the city’s elite. The San Diego Evening Tribune wrote “Hanging is none too good for them, and they would be much better off dead; for they are absolutely useless in the human economy.”