Former French Economy Minister François Baroin has confirmed that during last November’s European financial crisis, which brought down the Greek and Italian governments, French officials planned for the exit of Greece, Italy and of France itself from the euro zone. At the time, European officials denied that they were discussing any country’s exit from the euro zone.

The revelations are described in advance reviews of Baroin’s book, Crisis Notebook, describing his time as budget and then economy minister in 2010-2012 under conservative President Nicolas Sarkozy. His account reveals how the leading imperialist powers ruthlessly and undemocratically threw out governments to force through unpopular social cuts, while describing the enormous international tensions building up inside Europe.

Baroin recounts the tense November 3, 2011 G20 summit in Cannes, France. At the time, Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou had just called for a referendum in Greece on new austerity measures dictated by the European Union (EU). US President Barack Obama, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and Sarkozy demanded that Papandreou “explain himself.”

Baroin writes, “There was a standoff between Papandreou, who was with his finance minister. Sarkozy shouted out to the Greek prime minister, ‘We tell you clearly, if you do this referendum there is no rescue package for you.’ Papandreou pretends not to understand. With a steely look, Merkel very firmly tells him the same thing. … [Papandreou] sweats more and more, vacillates in his comments, then collapses. Trapped, he can only say yes or no to the euro, he understands he cannot evade this question by putting it to his people. I saw his political death, live.”

Washington, Berlin, and Paris were intervening to insist that Papandreou could not even have the fig leaf of a referendum to justify his unpopular austerity measures. Were the referendum vote to proceed, risking a popular rejection of the European bourgeoisie’s economic policies, the EU and IMF would step in. They would cut off Greece’s access to credit, forcing Athens to either accept state bankruptcy or to start printing its own currency to finance itself, thus leaving the euro.

Shortly before the meeting, moreover, Papandreou had sacked the entire top leadership of the Greek armed forces. This led to widespread suspicion that the Greek army, whose ties to US intelligence agencies go back to the 1946-1949 Greek Civil War and the 1967 CIA-backed junta, had considered launching a coup after the referendum was announced. (See: “Are Obama and NATO plotting a military coup in Greece?”) A week later, Papandreou was replaced by a new Greek prime minister, Lucas Papademos.

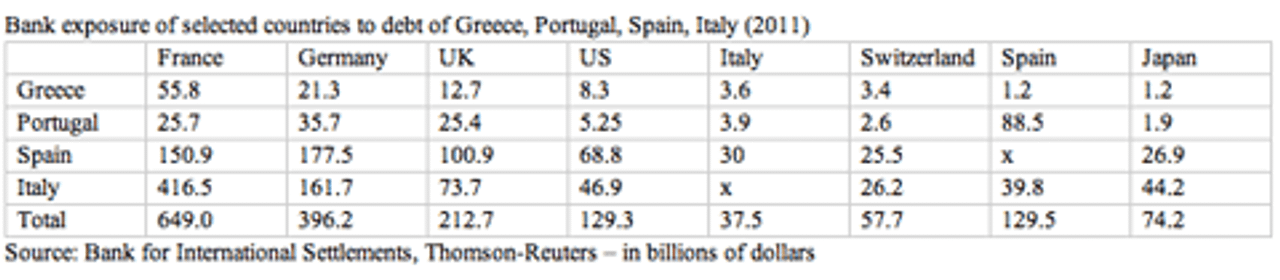

The meeting then turned to forcing out Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. Italy was too large to deal with like Greece: threatening it with state bankruptcy risked sinking the global financial system under bad debt. Baroin notes, “If Italy goes, everybody goes. It’s really too big. It’s the world’s eighth largest economy. The euro would not survive it.”

As a result, the ruling class sought to install a new government more closely aligned with the demands of the international markets. Baroin writes: “Berlusconi did not seem either to want to understand or admit that the problem of Italy was him. Without saying it explicitly, the message was very clear—all the protagonists told him. We forced Berlusconi to let the IMF have some control over Italy’s public accounts. Italy is proud. We knew that once he was back home, Berlusconi could not last long.”

As a result, the ruling class sought to install a new government more closely aligned with the demands of the international markets. Baroin writes: “Berlusconi did not seem either to want to understand or admit that the problem of Italy was him. Without saying it explicitly, the message was very clear—all the protagonists told him. We forced Berlusconi to let the IMF have some control over Italy’s public accounts. Italy is proud. We knew that once he was back home, Berlusconi could not last long.”

Five days later, Berlusconi announced that he would resign after shepherding one last raft of social cuts through the Italian parliament. He installed a so-called “technocratic” government in Italy that has pushed through wave after wave of social cuts.

Baroin was also preparing a secret government study group to make preparations for “the most somber hypothesis of our modern economic history”—a potential French exit from the euro. At the time, he writes, “The European Union was in a cyclone and the euro was attacked on all sides … The worst [possibility] was a Greek exit from the euro, contagion, a domino theory that would lead to the break-up of the euro zone and the de facto exit of France.”

Baroin’s account underscores the bankruptcy of European capitalism, as the political and financial brinksmanship through which it enforces devastating austerity measures on the population further undermines bourgeois Europe’s tottering institutional foundations.

These tensions surfaced in the spring of 2010, after bitter divisions between Berlin and Paris over German opposition to a first bailout package to pay off banks holding Greek debt. Then-European Central Bank (ECB) director Jean-Claude Trichet commented that European politics faced its deepest tensions since World War II (See, “The specter of catastrophe returns”).

As was remarked at the time, the preservation of the euro is for European imperialism not only a financial issue, but also one of regulating the potentially explosive international conflicts inside Europe that twice in the 20th century led to world war.

The Süddeutsche Zeitung offered the following scenario for the collapse of the euro: “The European Union collapses, as its most important political clamp, the common currency, disintegrates. Twenty-seven nation states again fight for markets. Germany, as the largest country with a healthy industrial structure, acquires enemies, and is possibly boycotted: the specter of the ‘Hegemonic Power’ is revived.”

Two years later, the economic slump and the intra-European struggle for markets have only deepened, and the euro has held together only due to multi-trillion-euro injections of cash from the ECB to calm recurring financial panics. Baroin’s comments indicate that the bourgeoisie in each European country is preparing the most extreme and ruthless measures to expand its wealth at the expense of the working class and of its international rivals.