"[They] call me ‘the socialist painter.' I accept that title with pleasure. I am not only a socialist but a democrat and a Republican as well--in a word, a partisan of all the revolution and above all a Realist ... for ‘Realist' means a sincere lover of the honest truth." [1]

While artists go in and out of fashion for various reasons, the renewed interest of late in French painter Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) corresponds to a turn in the contemporary art scene toward a model of the political artist and a rediscovered conception of realism that is encouraging. The retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum in New York this past spring was the first time since the centenary of Courbet's death thirty years ago that such a large exhibition of this far from obscure painter's work has been mounted. A smaller exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 1988 followed the centenary show in London and Paris, but there has been no significant exhibition since then in the United States.

In his own lifetime Courbet's larger-than-life image as an artist with political "attitude" earned him censure from bourgeois circles. Ridiculed in the popular press of the day as arrogant and uncouth and a poor painter, Courbet, far from being stung by the criticism, proudly proclaimed himself to be "the proudest and most arrogant man in France."

The Metropolitan's exhibition perhaps overemphasized this image of Courbet as an attention-hound whose egotism welcomed scandal. Egotism and ambition were undeniably aspects of Courbet's personality, but these characteristics were not just the self-aggrandizement of a career-driven artist. In a larger sense, they were an expression of the revolutionary confidence of Courbet's generation, reflecting the emergence of the modern working class and its first political awakening. Why should only rotten people be presumptuous?

For it cannot be emphasized enough that Courbet's artistic career opened with the Revolution of 1848 and closed with the Paris Commune of 1871. While the degree to which he participated directly in these events has been questioned, on the one hand, and held against him, on the other; his assertive self-confidence and impassioned belief in the artist's role in leading "the people"--broadly conceived--into a free and egalitarian future were shaped by these events.

Surely these were heady days of class and political conflict, from the Revolution of 1848, when the working class first entered the scene as an independent social force--only to be bloodily suppressed by the bourgeoisie and petty bourgeoisie--to the Parisian workers subsequent, albeit brief, seizure of power in the Commune.

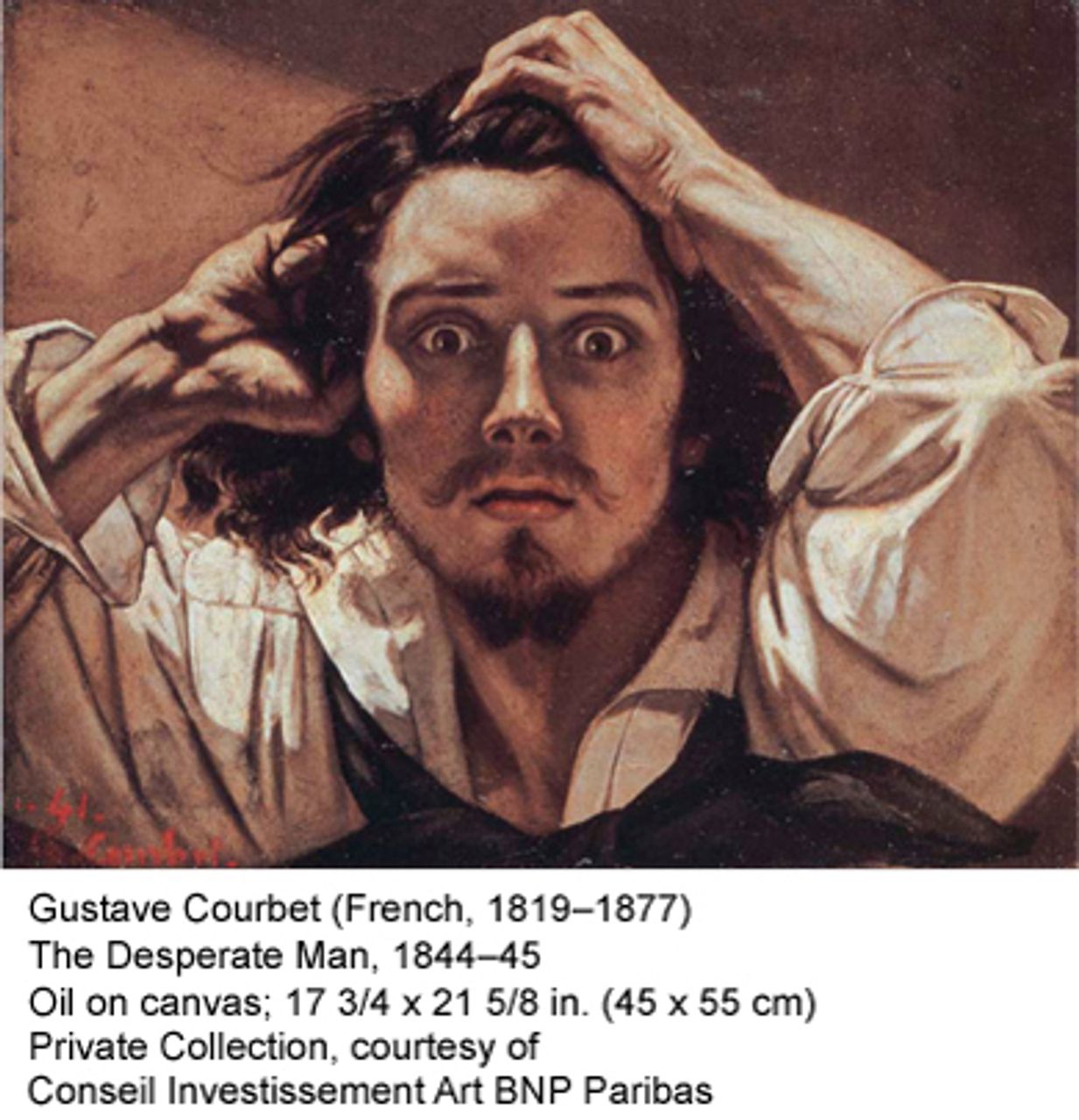

The first room of the exhibition displayed eighteen of Courbet's youthful self-portraits from the 1840s. In these wonderful, mostly small works, one can see how the artist hones his technical skills while trying out a variety of melodramatic and mannered poses. He goes from the bohemian dandy in checked pants to the wounded Romantic lover, from the rustic pipe-smoker in a fustian cap to the man driven to desperation by love or some other unspecified anguish.

In all of these works, painted no doubt by regarding himself in the mirror, the young man confronts the viewer with an intense, yet languid gaze. His heavy lids and full lips, often pursed on the stem of a pipe, are at once sensuous and defiant. Full of dramatic gesture and high contrast between light and dark, these pictures sum up the painter's assimilation of key artistic traditions, among them the chiaroscuro of an Italian Baroque master like Caravaggio (c.1571-1610), as well as the expressiveness of the portraits of Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669).

In all of these works, painted no doubt by regarding himself in the mirror, the young man confronts the viewer with an intense, yet languid gaze. His heavy lids and full lips, often pursed on the stem of a pipe, are at once sensuous and defiant. Full of dramatic gesture and high contrast between light and dark, these pictures sum up the painter's assimilation of key artistic traditions, among them the chiaroscuro of an Italian Baroque master like Caravaggio (c.1571-1610), as well as the expressiveness of the portraits of Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669).

His emphasis on self-reflection, by turns stormy and melancholic was characteristic of the Romantic painters--known as the Generation of 1830--who immediately preceded Courbet: Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863). Géricault's Raft of Medusa (1818-19) and Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (1830) were important precedents for Courbet's work, in particular for their attitude toward the immense significance of contemporaneous events.

In contrast to most artists in the mid-1800s, who would have been trained at the Académie des Beaux-Arts which, through its Salon, ruled the art world, Courbet mostly taught himself to paint by studying the masterpieces in the Louvre.

He was born the son of a prosperous landowner in Ornans in Franche-Comté ("Free Country"), an area in eastern France that had been formally annexed by the monarchy in the 17th century, but maintained a spirit of independence and pride in its provincial traditions.

Although he may have rejected his father's ambition that he become a lawyer--thereby completing the family's rise in fortunes from the peasantry to the petty-bourgeoisie and into the bourgeoisie itself--Courbet maintained his own grand aspirations, in keeping with the shifting class relations and philosophical outlook of the times.

At school in the provincial seat of Besançon, his drawing instructor had his students draw from nature, contrary to the standard academic studio training. His philosophy instructor would have been Charles-Magloire Bénard, one of the first to translate the work of G.W.F. Hegel (1770-1831) into French.

When Courbet finally convinced his father to let him go to Paris in 1839, he was immediately immersed in the bohemian world of café society and political upheaval. The Bourbon Restoration had been overthrown in the July days of 1830 and replaced by Louis-Philippe's Orléans regime through which the bourgeoisie sought to rule. But it was challenged from all sides-from Legitimists who wanted to restore the ançien regime, to the Bonapartists, as well as from old republicans of the Revolution of 1789, who saw their principles of "Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité!" betrayed by the bourgeois regime's scramble to appropriate for itself the privileges of the old aristocracy.

Trotsky once noted the political atmosphere Courbet would have encountered when he arrived in Paris. "In 1840, almost half a century after the government of the ‘Mountain,' eight years before the June days of 1848, [the German poet Heinrich] Heine visited several workshops in the faubourg of Saint-Marceau and saw what the workers, ‘the soundest section of the lower classes,' were reading. ‘I found there,' he wrote to a German newspaper, ‘several new speeches by old Robespierre and also pamphlets by Marat issued in two-sous editions; Cabet's History of the Revolution; the malignant lampoons of Cormenin; the works of Buonarroti, The Teachings and Conspiracy of Babeuf, all productions reeking with blood ... As one of the fruits of this seed,' prophesies the poet, ‘sooner or later a republic will threaten to spring up in France.'" [2]

Louis-Philippe, the "bourgeois king," was dependent from the outset on the big bourgeoisie that controlled the rapidly expanding trade and industry of France. And then two world events, the crop failures and potato famine in 1845-6 and the trade crisis of 1847, immediately precipitated the February Revolution in 1848.

Courbet does not seem to have participated in these events, nor did he depict them, as did other artists at the time, such as the renowned painter and caricaturist, Honoré Daumier (1808-79). Even the preeminent academic painter of battle scenes and military maneuvers, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (1815-91), painted the bodies of Parisian workers left on the cobblestones in his painting The Barricade (1848).

However, Courbet was undoubtedly influenced by the fever pitch of events and the possibility of the old regime of prestige and privilege being swept away by the masses and a new social order established. Between 1848 and 1855, in rapid succession, he produced his definitive life's work, a series of overwhelming large and ambitious paintings that would define almost single-handedly the artistic movement soon to be dubbed Realism, somewhat disparagingly, by poet and critic Charles Baudelaire (1821-67)--whose portrait Courbet also managed to paint, in 1848 no less!

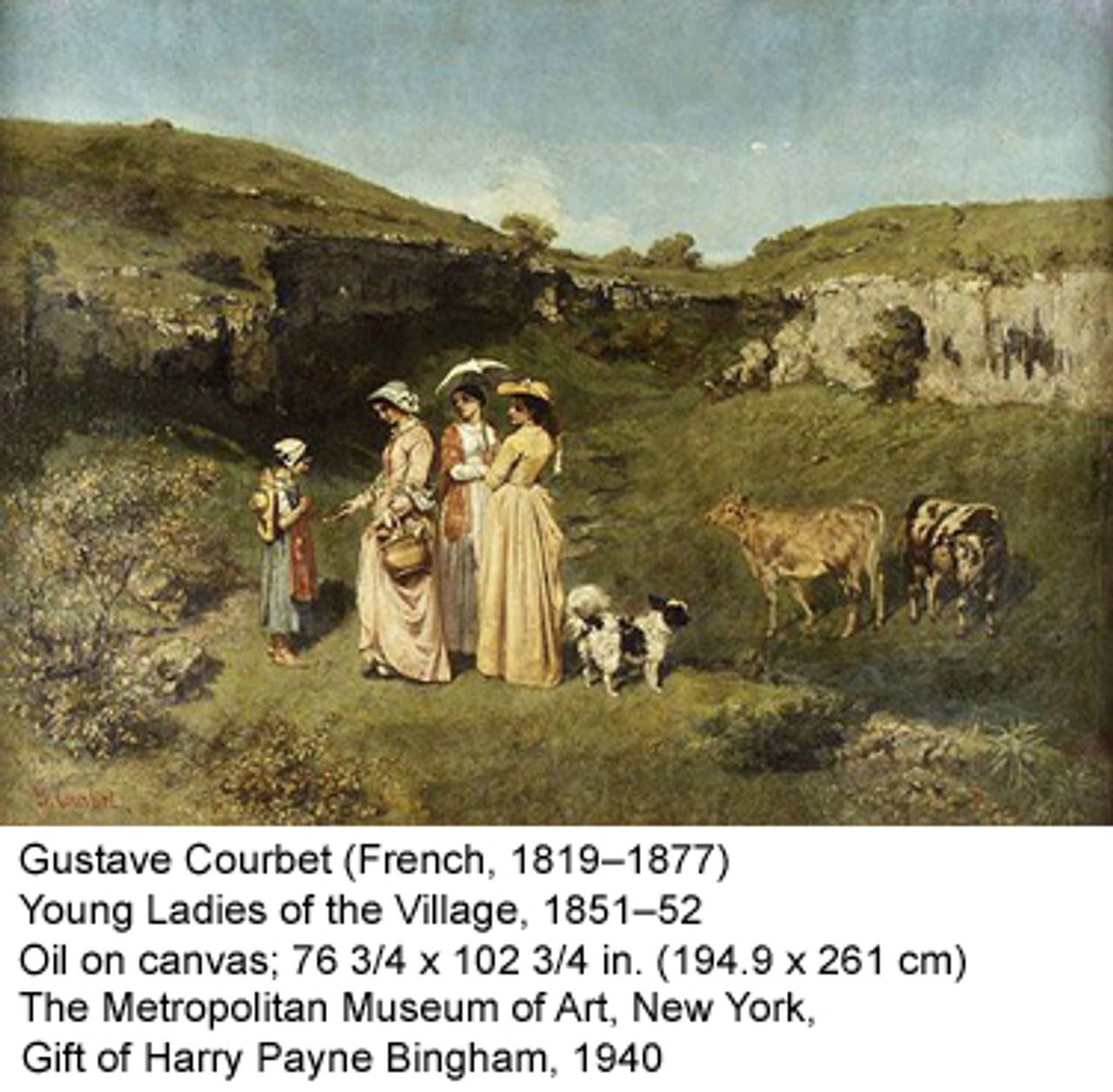

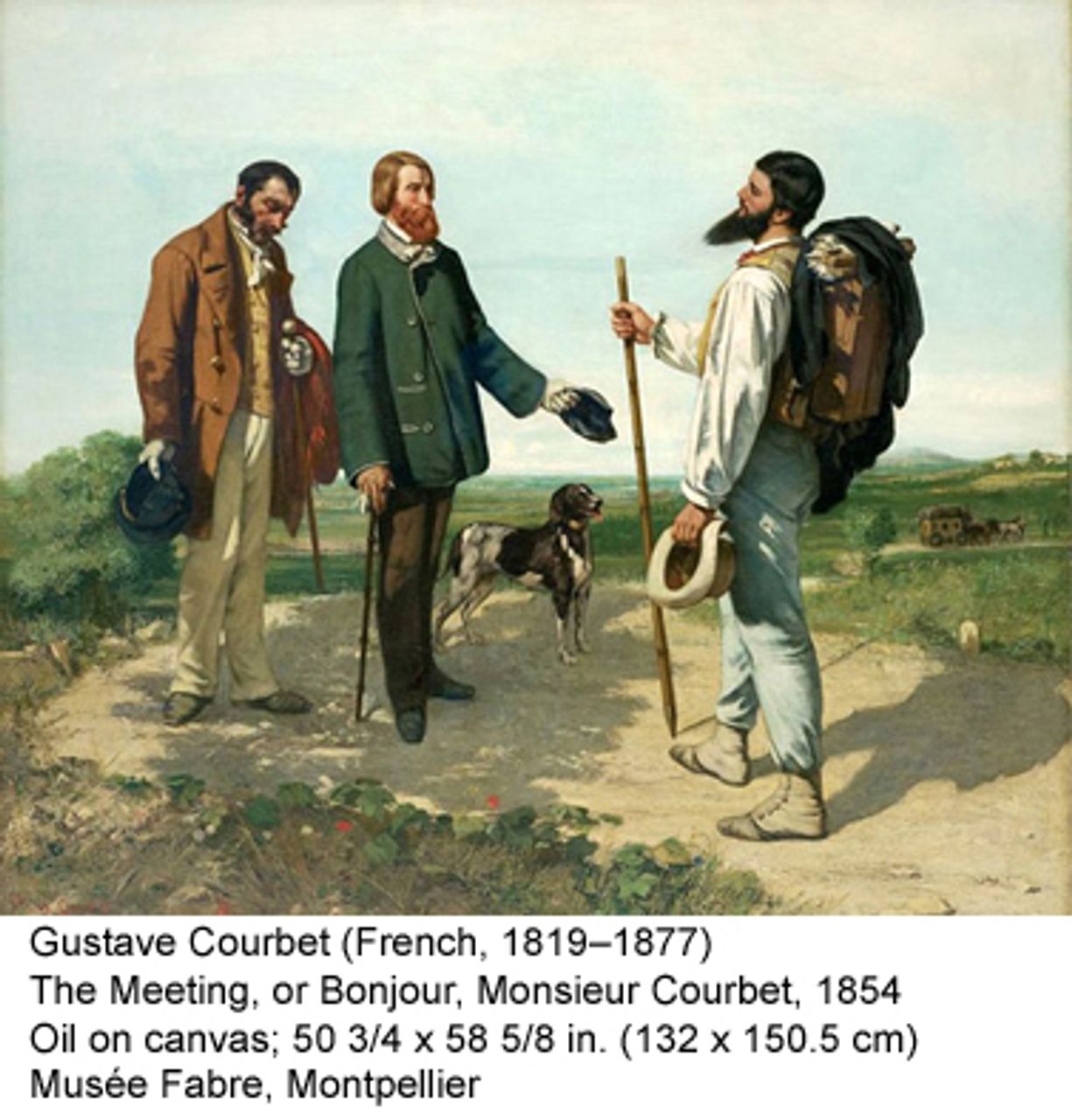

These were After Dinner at Ornans* (1848-49), The Stonebreakers (1849-50, destroyed 1945), Burial at Ornans (1850), The Peasants of Flagey Returning from the Fair* (1850-55), Preparation of the Bride/Dead Girl* (unfinished, 1850-54), Young Ladies of the Village* (1851-52), The Grain Sifters (1854), The Meeting, or Bonjour M. Courbet* (1854) and culminating in the massive Painter's Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up a Seven-Year Phase of My Artistic Life (1855). (Paintings marked with asterisk were included in the Metropolitan Museum exhibition).

These were After Dinner at Ornans* (1848-49), The Stonebreakers (1849-50, destroyed 1945), Burial at Ornans (1850), The Peasants of Flagey Returning from the Fair* (1850-55), Preparation of the Bride/Dead Girl* (unfinished, 1850-54), Young Ladies of the Village* (1851-52), The Grain Sifters (1854), The Meeting, or Bonjour M. Courbet* (1854) and culminating in the massive Painter's Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up a Seven-Year Phase of My Artistic Life (1855). (Paintings marked with asterisk were included in the Metropolitan Museum exhibition).

Several of these paintings are of a scale that makes them too large and fragile to transport, particularly Burial at Ornans (315 x 668 cm, 124.5 x 263.75 in.) and The Painter's Studio (359 x 598 cm, 142.25 x 235.5 in), which are on view at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (although the exhibition in New York tried to recreate the latter by showing some of the smaller portraits that Courbet incorporated into his magnum opus.)

It was not particularly radical in itself to depict the peasantry in art. The life of the French peasant was the focus of various regionalist painters, most notably Jean-François Millet (1814-75). A peasant himself, Millet initiated the Barbizon school of painting, and was thought to be a socialist in his views. There were also innumerable lesser painters who depicted peasants sowing and harvesting the fields, gathering in rustic churchyards or enjoying a tankard at the inn, but their emphasis was on the humble and seemingly eternal aspects of such activities. For the most part, their works were genre scenes.

Courbet, on the other hand, gave these activities historic specificity and importance, with the scale to match. But his paintings are imposing not just because of their physical size. They gave their seemingly mundane subject matter such serious consideration that they annoyed and bewildered viewers and critics, one of whom commented on After Dinner at Ornans that "no one could drag art into the gutter with greater technical virtuosity" than Courbet. [3]

After all, according to the taste of the time, art was supposed to be elevating and beautiful, transporting the viewer into an idealized world peopled with mythical beings or the wealthy. To see the dreary reality that surrounded one every day--who needed to look at a painting to do that?

In After Dinner at Ornans, four men, one of whom was modeled on the painter's father, sit half asleep listening as one of them plays the fiddle. Two men sit with their backs to the viewer, close up to the front plane of the picture. A dog sleeps under a chair. The low-ceilinged room is engulfed in darkness with the exception of the white tablecloth and the coat of the man lighting his pipe from a burning stick pulled from the grate.

Despite its grand scale, nothing noteworthy seems to be going on. Nevertheless, the scene suggests a latent, threatening social force that might, like the glowing ember that is the only spark of life in the painting, burst into flame at any moment.

For the peasants in Courbet's paintings were not the pious, long-suffering types usually depicted in genre scenes. He depicted the milieu of petty bourgeois landowners with which he was most familiar from his own family, as well as the increasingly proletarian farm laborer, for example, in The Stonebreakers--a painting destroyed in the Allied fire-bombing of Dresden in 1945 and known only through reproductions.

As art critic Linda Nochlin writes, "The stone-breaker became a popular subject for artists concerned to create an image of the rural toiler, but none quite so stark or so down-to-earth in simply confronting us with the detailed facts of the situation as [Courbet] ... He was in fact criticized at the time for making his stone-breakers look no more important than his stones." [4]

Courbet's paintings communicate the explosive potential of the increasingly proletarian farm laborer that became all the more threatening in the context of the Revolution of 1848. His paintings have a grandeur of scope and purpose--even to the point of sometimes over-reaching and failing as integrated compositions--which made them, and Courbet himself, draw an enraged and antagonistic response from his critics. (For caricatures of the artist that appeared in the press at the time, see here.)

The revolutionary wave of 1848 not only proclaimed equality between landowners and farm laborers, it championed an aristocracy of talent--and artistic talent was considered the ultimate talent--over a system of privileges. The Salon jury of 1848 was replaced with a more representative body that included more artists from the new generation, not just academicians.

As a result, all of Courbet's entries to the 1848 Salon were accepted. The Salon of 1850-51 was an even greater success--his Stonebreakers, A Burial at Ornans and The Peasants of Flagey, as well as several smaller works, were all exhibited. He had effectively become the most famous, or infamous, painter in France overnight.

However, this did not end Courbet's difficulties with officialdom. The wave of revolution in 1848 was followed by a period of reaction. Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew, Louis Napoleon (he of Marx's 18th Brumaire), seized power, and the bourgeoisie firmly established itself as the new ruling elite, repressing the working class to do so. Although Courbet believed he could continue to paint whatever subjects he wished, he had to appeal to the Salon and increasingly to wealthy bourgeois patrons for support.

Courbet's belief in a meritocracy of equals, with the artist in fact somewhat superior to the good bourgeois gentilhomme, underlies another painting included at the Met, The Meeting, or Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet,(1854). Here the painter depicts himself as a man of the road, a rucksack on his back, meeting his wealthy patron Alfred Bruyas on the road from Ornans. The full figures standing in the bright open landscape have a "hail and well-met" appearance that speaks not just to a specific incident, but communicates Courbet's enthusiasm at having found in his patron a "fellow traveler."

Courbet's belief in a meritocracy of equals, with the artist in fact somewhat superior to the good bourgeois gentilhomme, underlies another painting included at the Met, The Meeting, or Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet,(1854). Here the painter depicts himself as a man of the road, a rucksack on his back, meeting his wealthy patron Alfred Bruyas on the road from Ornans. The full figures standing in the bright open landscape have a "hail and well-met" appearance that speaks not just to a specific incident, but communicates Courbet's enthusiasm at having found in his patron a "fellow traveler."

Bruyas had met Courbet in 1853 when he commissioned a portrait, and in the process had his own artistic sentiments awakened. If he did not become an artist himself, at least he became an enlightened patron. This possibility excited Courbet, who welcomed Bruyas as a kindred spirit who would help him "live on my art for all of my life, without ever departing an inch from my principles, without ever for an instant lying to my conscience ... I am right! I am right! I have met you. It was inevitable because it is not we who have encountered each other but our solutions." [5]

In 1855, when Courbet's Burial at Ornans (1850) and The Painter's Studio (1855) were rejected for the Universal Exposition of that year--most likely on account of their massive size rather than their content, since other smaller works of his were accepted--the painter set up a private pavilion and charged the public admission to see forty of his works right across from the entrance to the fairgrounds. Such a one-man exhibition, made possible by Bruyas' financial support, was highly unconventional and provocative. To go with the exhibition, Courbet issued his Realist Manifesto.

The pamphlet is only four paragraphs long and sums up the painter's artistic creed. It remains a powerful statement of what is meant by "Realism" in art, as distinct from realistic or even representational styles, with which the term has subsequently become identified. In fact it defines no particular style of painting, but rather proclaims an attitude toward reality itself, which includes the artist's relationship to tradition, and toward his own individuality as the embodiment of his times.

"I have studied, apart from any preconceived system and without biases, the art of the ancients and the moderns. I have no more wished to imitate the one than to copy the other; nor was it my intention, moreover, to attain the useless goal of art for art's sake. No! I simply wanted to draw forth from a complete knowledge of tradition the reasoned and independent understanding of my own individuality.

"To know in order to be capable, that was my idea. To be able to translate the customs, idea, the appearances of my epoch according to my own appreciation of it [to be not only a painter but a man,] in a word to create living art, that is my goal." [6]

However, Courbet's belief that the relationship between patron and artist could be a fully equal and mutually beneficial one proved as mistaken as the belief that the bourgeoisie and workers shared the same fundamental social interests. His relationship with Bruyas cooled. As a result, Courbet had to paint on commission a good many portraits of sitters who did not inspire him, and his lack of interest is communicated in their unremarkable quality. Several of these paintings were on view at the Met. Of one of these portraits, Courbet remarked that at least he could turn such work out fast.

A portrait of much greater significance included at the Met is that of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-65), the anarchist philosopher who dominated the French utopian socialist movement in the 1850s. Like Courbet, Proudhon hailed from Besançon; they had met back in school. However their friendship developed after Proudhon moved to Paris in 1847. Ten years Courbet's senior, he became a friend and mentor, his petty-bourgeois version of socialism exerting a strong influence on Courbet's concept of himself as a socialist.

Karl Marx, on the other hand, born a year before Courbet, rejected Proudhon's views, subjecting them to sharp criticism in his Poverty of Philosophy. This was not a transition that Courbet ever made; he remained a utopian socialist, to the extent that he consistently held any defined philosophical outlook, to the end of his life.

Despite their friendship and collaboration on a treatise on the social utility of art, Courbet did not paint the portrait of his friend till after Proudhon's sudden death in 1865. Grief-stricken, Courbet felt, "the nineteenth century has just lost its guiding force and the man who embodied it. We are left without a compass, and mankind and the revolution, adrift without his authority, will once again fall into the hands of soldiers and barbarism." [7]

The fairly large canvas (58 x 78 in/147 x 198 cm) was thus drawn from photographs and memory. Intended as a "historic portrait" in which the philosopher--wearing a loose workman's blouse, sitting on low steps, his elbow on his knee, chin in hand--is meant to embody the spirit of the revolution. Humble and unassuming yet intellectual, surrounded by his open books and notes, the philosopher looks contemplative, a bit dreamy in a domestic setting. His young daughters play on the ground by his side, and originally Mme. Proudhon sat in the wicker chair.

Based as it was on multiple sources (including not just photographs, but possibly other artworks such as Raphael's School of Athens (1510-11), with the solitary philosopher in the foreground), the painting has a somewhat awkward character; the figures don't seem to belong together in their space. Nevertheless, the painting strongly conveys Courbet's identification with his mentor--who could be an artist no less than an artisan--for he thought of himself as the heir to Proudhon's ideas.

"Like Proudhon, I will not have the revolution derailed," Courbet exclaimed in a letter, "The revolution must return to the right people." [8] Though full of heated pronouncements against the authorities that were usurping the revolution, Courbet, as a follower of Proudhon, had only a limited sense of what would stop this process. He concentrated his energies on defending freedom of artistic expression, espousing Proudhon's anarchistic principles while challenging the norms of bourgeois taste, the officialdom of the Salon and Emperor Napoleon III himself.

He continued to do this in a variety of ways over the course of the 1860s. He produced a number of exceptionally sensual and scandalous nudes during this period, two of which--Sleepand The Origin of the World (both 1866)--were commissioned by the Bey of Turkey for his private delectation.

The Met rather prudishly exhibited the latter behind a partition, together with contemporaneous erotic photographs that might have been sources. But Courbet's eroticism has more to do with the way he paints women's bodies than with pornographic intent per se. They seem at once sumptuous yet not idealized, exuding an intense, absorbed sexuality that carries a certain shock value even today.

The Met rather prudishly exhibited the latter behind a partition, together with contemporaneous erotic photographs that might have been sources. But Courbet's eroticism has more to do with the way he paints women's bodies than with pornographic intent per se. They seem at once sumptuous yet not idealized, exuding an intense, absorbed sexuality that carries a certain shock value even today.

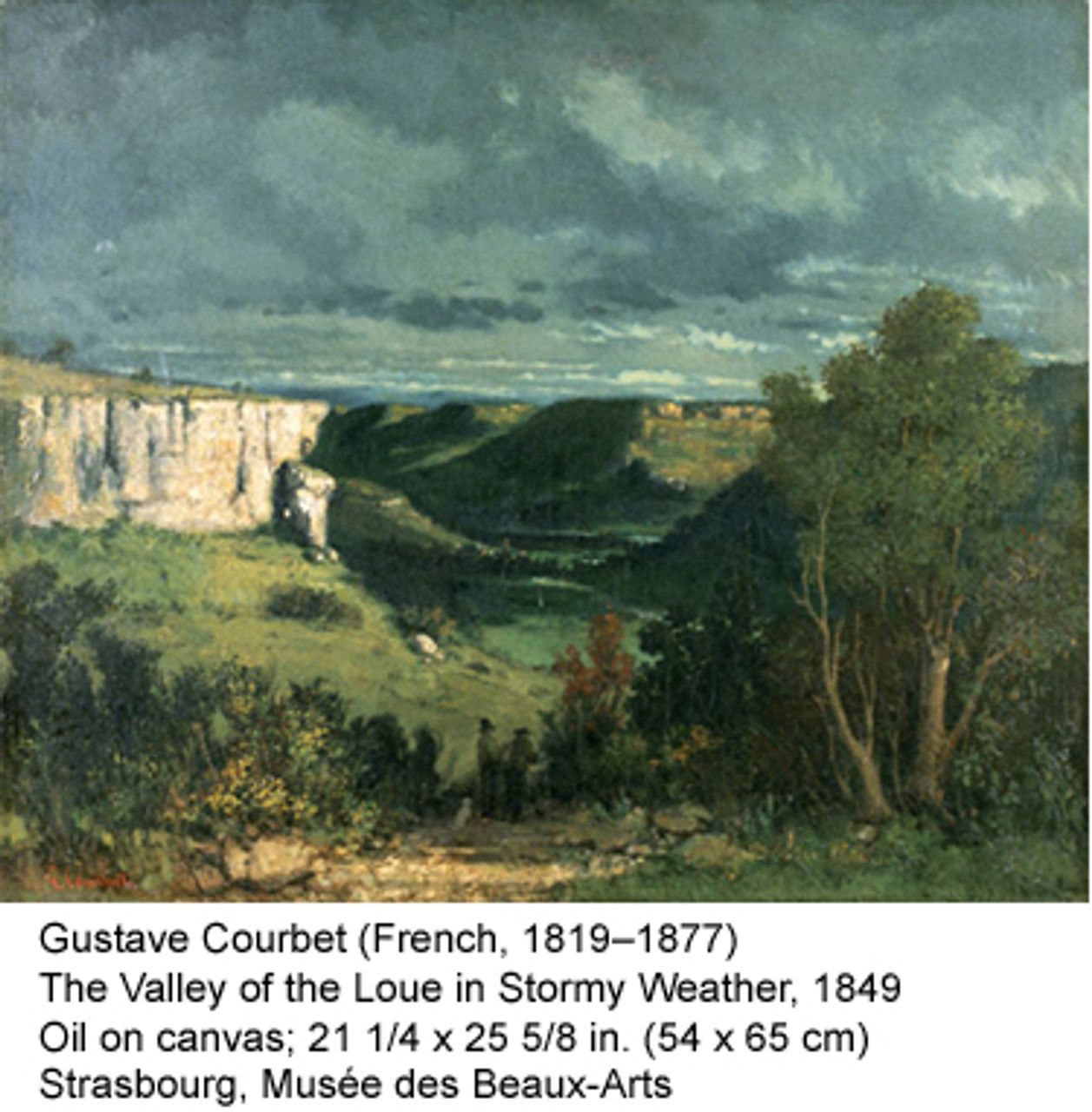

The Met exhibition also included a good number of Courbet's perhaps less-well-known landscapes, many of them of the limestone cliff ledges surrounding Ornans, stormy seascapes from his stays at the Normandy coast, as well as his surprising forest scenes of deer and huntsmen, for Courbet loved to hunt. In addition, no one could paint snow and wild animals quite like Courbet, as can be seen in The Fox in the Snow (1860).

Then in 1870, events thrust Courbet into a more direct political role. As the Second Empire of Napoleon III began its ignominious collapse, Courbet added his fuel to the fire, refusing the Emperor's award of the French Legion of Honor, declaring "The state is incompetent in artistic matters ... The day it lets us be free, it will have fulfilled its duty toward us ... Let me end my life as a free man." [9]

Then with the debacle of the Franco-Prussian War, Paris fell under siege. Courbet and other artists, including Edouard Manet stayed in the blockaded and soon starving city. (Impressionist painters Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro fled to England.) Courbet was elected the head of the Arts Commission tasked with protecting the public art collections from destruction by the Prussian army or pillage by the Bonapartist curators.

With the seizure of power by the working population in March 1871 and the establishment of the Paris Commune, Courbet published an open letter as president of the Arts Commission calling for artists to have complete independence from the government and full responsibility for the administration of artistic affairs, from the maintenance of museum collections, to the selection of art works for the Salon and the awarding of public commissions and teaching appointments. He was popularly elected to the Municipal Council of the Commune, where he wrote to his family, "I sit and I preside twelve hours a day. My head is beginning to feel like a baked apple." [10]

The culmination of Courbet's political career as a Communard was the destruction of the Vendome Column, a monument to the military victories of Napoleon Bonaparte made out of the cannons captured at the Battle of Austerlitz (1805), although the painter was not in fact the primary instigator. He had called for the column's dismantling back in 1870, for he said it lacked all artistic merit and served only to perpetuate imperial war and conquest, but the actual decree for its destruction was passed before Courbet was elected to the Commune.

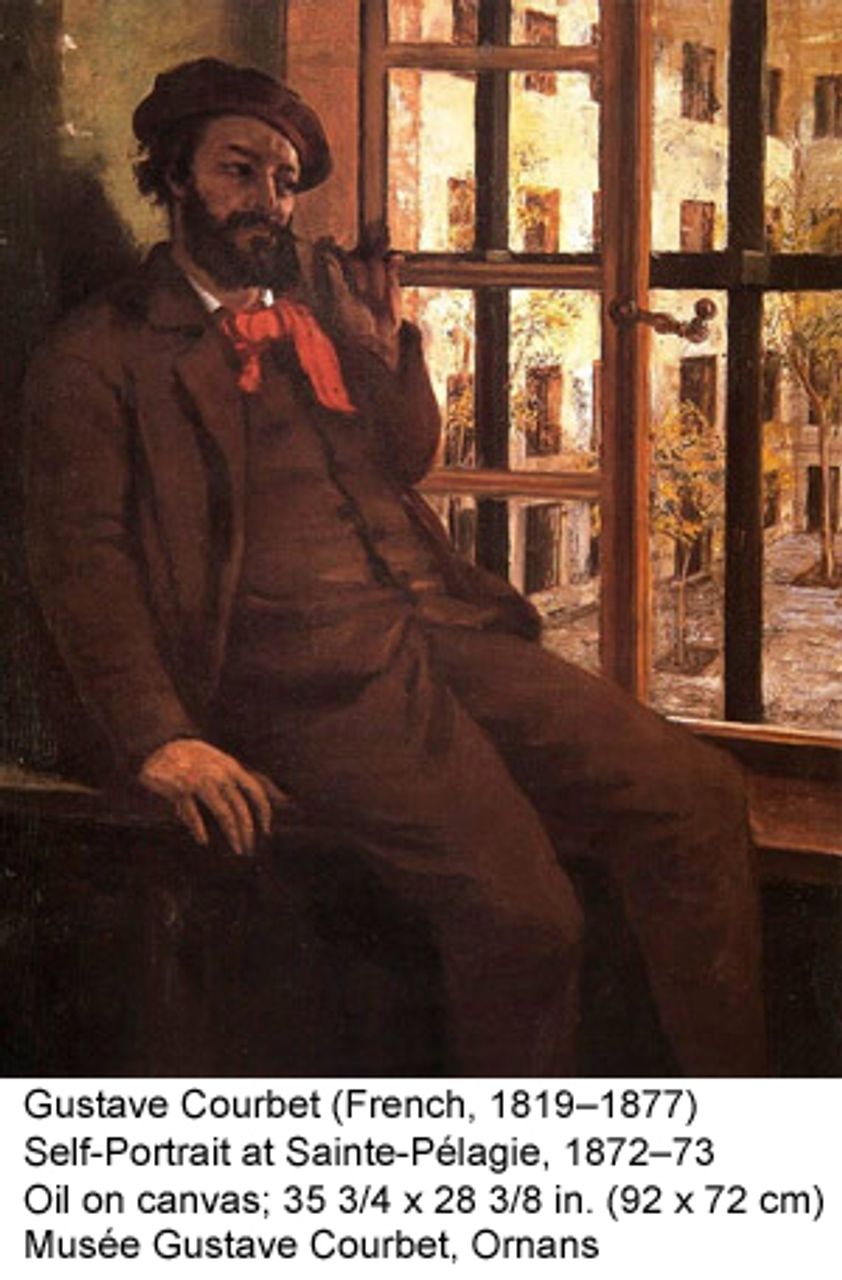

Nevertheless, when the Versailles forces retook Paris in June 1871, the destruction of the monument incensed them and Courbet was their scapegoat. For his participation in the Commune, he was sentenced to serve six months in Sainte-Pélagie prison, and pay a fine. Many thousands of Communards were exiled or shot.

He served his time in prison, though increasingly in poor health and dispirited, but never entirely without a touch of characteristic self-importance--and self-pity. He painted a few self-portraits and still-lifes; he maintained a surprising gift for painting fruit and flowers with a riotous richness similar to his nudes. Once released, he was beset by his enemies, their viciousness emboldened by the reactionary atmosphere.

He served his time in prison, though increasingly in poor health and dispirited, but never entirely without a touch of characteristic self-importance--and self-pity. He painted a few self-portraits and still-lifes; he maintained a surprising gift for painting fruit and flowers with a riotous richness similar to his nudes. Once released, he was beset by his enemies, their viciousness emboldened by the reactionary atmosphere.

In 1873, he took refuge in Switzerland, and while he still earned large sums for his paintings, he was afraid of having them confiscated by the state because in his absence he had been judged financially responsible for the full cost of rebuilding the Vendome column, which came to the enormous sum of more than 300,000 francs.

Although he no doubt longed to return to France, he said he would not do so while his fellow Communards were in exile. Drinking heavily and taking absinthe, his health deteriorated and he died on January 3, 1878 at the age of 58. The contents of his studio were sold to pay the debt on the Vendome Column. Just two years later in 1880, an amnesty was proclaimed for the Communards to return to France and have their fines annulled. But Courbet's body was not returned to France for burial till 1919, the centenary of his birth.

The final paintings in the Metropolitan Museum's exhibition were the two versions Courbet did of The Trout (1872 and 1873). With slight variations, both paintings are close-ups of a single fish, caught on the fisherman's hook and hauled up on the rocky shore. With its wide open mouth, staring eye, and bloody gills, the fish is on the brink of death, gasping not for air, but to be released back into the water, into freedom.

The paintings have been noted for their remarkably free, nearly abstract handling of paint, a harbinger of the approach to be taken by the Impressionists who would soon dominate the art world of the 1880s. The way in which they resemble traditional still-lifes of dead deer, rabbits, etc., yet elicit empathy for the victims is also unusual. Perhaps most of all, they are a fitting closure to the career of an extraordinary painter--one who felt he could achieve both artistic and human freedom through his work. Courbet indeed fulfills his own goal, namely he has created a living art that translates the ideas--and ideals--of his epoch. He remains an inspiration for ours.

Gustave Courbet, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, February 27, 2008-May 18, 2008. The exhibition began at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, and continues to the Musée Fabre in Montpellier.

Images from the exhibit included in this review courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. For additional images, see: http://www.metmuseum.org/special/gustave_courbet/images.asp

Notes:

1. Gustave Courbet, Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition catalogue (New York: Hatje Cantz, 2008) p. 19. (Quoted from Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Correspondences de Courbet, 1996, p. 97.)

2. Leon Trotsky, The Permanent Revolution and Results and Prospects (London: New Park Publications, 1962, reprinted 1975) p. 187.

3. James Rubin, Courbet (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1997, reprinted 2003) p. 51.

4. Linda Nochlin, Realism (London: Penguin Books, 1971, reprinted 1990) pp. 120-21.

5. Catalogue, pp. 214-15 (Quoted from Chu, 1992, p. 122, letter 54-2.)

6. Rubin, pp. 157-58. (Translation of Courbet's On Realism)

7.Catalogue, p. 26 (letter to Gustave Chaudey, Jan. 24, 1865, quoted from Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate, Correspondences de Courbet, 1996, p. 231).

8. Ibid.

9. Rubin, p. 273.

10. Rubin, p. 276.