Mike Leigh is perhaps the most interesting British filmmaker of the past two decades. Nominated for five Academy Awards and the winner of accolades and prizes at every major international film festival, including Cannes, Berlin and Venice, Leigh has established himself as a significant figure in global cinema.

After more than a decade writing and directing for British television (Nuts in May, Abigail’s Party, Four Days in July and other works), he became known to a wide international audience with his Life Is Sweet (1991), an account of a deeply dysfunctional but strangely endearing working class family, and Naked (1993), a lacerating picture of alienation and frustrated idealism.

Leigh’s greatest box office success to date has been Secrets & Lies (1996), the story of a white woman who comes face to face with the half-black daughter she gave up for adoption years earlier. In Topsy-Turvy (1999), the filmmaker examined the artistic-theatrical process in a work about the Victorian lyricist-composer team of Gilbert and Sullivan. He treated the problem of illegal abortions in the 1950s in Vera Drake (2004).

Leigh (born 1943 in Salford), the director of 18 feature films in all, has been at work during a difficult political and cultural time—“impossible,” as he described it to me. In a generally bleak artistic landscape, he has stood out importantly as someone who has attempted to make complicated and sensitive—and socially engaged—films, also accessible to broad audiences. His method of building up characters and plots out of intense discussion and improvisation lasting months often yields remarkable results.

As Leigh notes, he is anything but a naturalist. He refers to his love of circus, vaudeville and theater. His films do not imitate everyday human activity, nor do his characters repeat ordinary conversation. The events and dialogue are deliberately heightened, as part of an effort to get behind the reality of day-to-day life. The exaggerated, sometimes grotesquely exaggerated, goings-on take their place in a certain British tradition. André Breton once commented something to the effect that there was no need for a surrealist movement in England because life and art there were already surreal enough.

One of Leigh’s most interesting features as a film writer and director has been his willingness to bite into reality at a somewhat different angle than both the British ‘neo-realists” of the early 1960s and director Ken Loach in his working class portrayals, along with the general school of “docu-” and “kitchen sink” drama. He has seemed considerably less parochial and “national” in this regard.

That his film career has had its share of ups and downs, veering occasionally toward sentimentality and occasionally toward condescension, owes much to the unfavorable climate. The Thatcherite counteroffensive against the working class and the protracted rightward lurch of the Labour Party and the trade unions, which entirely abandoned the population to its fate, have framed the past several decades. The systematic dismantling of the welfare state, the destruction of entire industries and communities, the attempt to eradicate social solidarity in favor of ruthless individualism and related socio-cultural processes have made their impact felt. In a traditional society such as Britain, the traumatizing consequences have been particularly severe.

More than he perhaps suspects or has intended, Leigh has registered and often critiqued these trends. He considers himself a socialist and a proponent of social equality. In person, he is intelligent, sometimes combative, always articulate. He hopes his next project will be a film about the great British painter J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), for which, disgracefully, the financing has been difficult to organize.

I began our discussion at his offices in London with a question about his most recent movie, Happy-Go-Lucky. I wondered how he responded to the comment that the film, about an irrepressible north London teacher, was “lightweight” in comparison to the best of his previous work.

Unsurprisingly, Leigh rejected the notion, arguing that the film was an examination of the real world, which had its “dark underside.” He referred to its “Chekhovian” sensibility and pointed out that Vera Drake, a pretty grim work, had had its tragicomic aspects.

Happy-Go-Lucky, the filmmaker continued, “confronts easy assumptions” about our present condition, by which I took him to mean easily gloomy or cynical assumptions. “Because we’re screwing up the planet and ourselves, and there’s a great deal to lament at present,” we should not forget that there are caring people teaching children, he pointed out.

He couldn’t understand the view of those who simply find the film’s central character, Poppy (Sally Hawkins), “irritating. I’ve heard people say, ‘I want to kill her,’ and I can’t understand that. You should love her by the end of the film.”

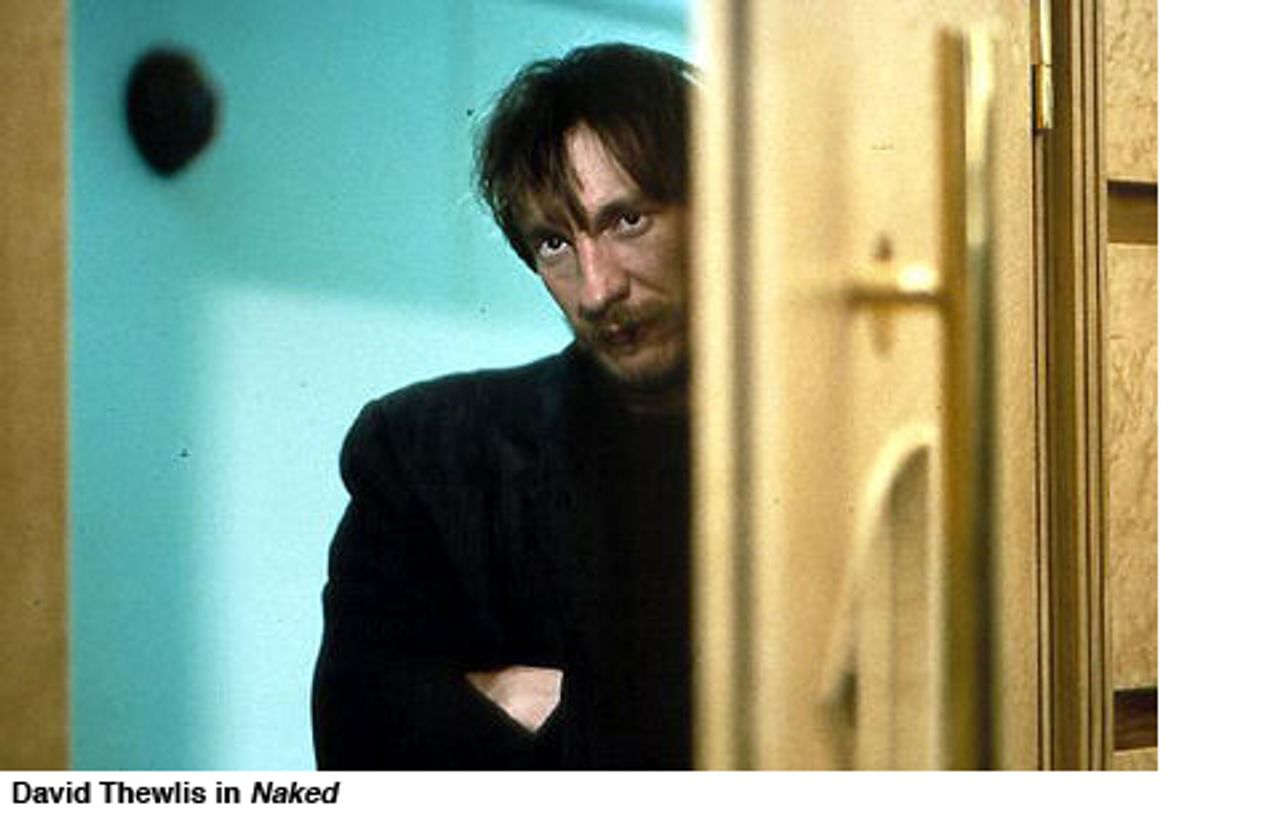

As for “dark” and “light,” Leigh asserted that Poppy and Johnny (David Thewlis), the angry lead figure in Naked, were “flip sides” of one another. “They complement each other. Johnny and Poppy are both idealists. They believe in certain values. Johnny, of course, is bitter, frustrated, he’s grown in on himself.”

Happy-Go-Lucky is about “what you don’t often see, teaching and learning.” There are teachers of various kinds in the film, including a flamenco teacher who brings her problems in love into the class. Leigh remarked that the moral there was “you leave your personal rubbish outside the classroom.”

When I mentioned that a teacher from north London had praised his movie for its verisimilitude, but noted that whereas in the film a social worker had arrived on the scene in two days to deal with a troubled child, she had been waiting for eight months for help, Leigh remarked, “That’s a valid criticism.” He acknowledged that Happy-Go-Lucky had not been first and foremost an exposé of the conditions in the British education system. You begin a film by intending to discuss “everything,” he said, and then you narrow it down to what you consider the most essential problems.

The conversation then carried on as follows:

David Walsh: One of the admirable features of your work is that it’s both artistically serious and popularly accessible. That’s unusual these days.

Mike Leigh: I don’t even think about that, consciously or self-consciously. That’s a given with me. My natural instinct is to communicate and entertain. I don’t regard my early and natural gravitation toward film, the theater, writing, etc., as being anything other than some natural and instinctive and compulsive gravitation toward show business, entertainment, making people laugh, a fundamental need to capture life and share it with people. In other words, I’m not one of those people who needs to say, “Well, we ought to strive to do something that’s kind of popular.”

On the other hand, I’m equally unafraid of confronting the audience with difficult and not always easily explicit notions. I think people, in the strict sense of the word, are entertained, and thereby stimulated, not only by being asked to care, and to enjoy, but also to think and have their emotions confronted by stuff.

DW: There are theories that to demonstrate artistic integrity is to be inaccessible, impossible for wide audiences to follow.

ML: Nonsense. It’s exactly those notions that lead me to say what I just have. I think it’s crap. It would be patronizing to both of us to recite the infinitely long list of artists of all kinds who simply remind us that the two things—artistry and popularity—are naturally and thoroughly compatible.

DW: Absolutely. At the same time, you have been making films in a difficult time, and often flowing against the stream.…

ML: Oh, an impossible context. You know, Ken Loach and I, and everybody else, from the late 1960s till the early 1980s, we couldn’t make feature films, we did it all in television, as you know very well. Incidentally, apart from everything else, in the context of the BBC “Play for Today” [anthology drama series, 1970-1984] and all that, I know from experience that one can reach wide audiences in a popular way.

You’re absolutely right, and you’ve already said this, the problem is not the work, one’s intentions, one’s work or anything else, it’s the bloody system that stands between the work and the audience. And also the indoctrination of the audience, as intelligent as they may be, to the assumption that a movie is a Hollywood movie. That is hardwired in by the very nature of the Hollywood machine and culture.

DW: And of course the “Hollywood movie” is something quite different from the “Hollywood movie” of half a century or more ago.

ML: That is absolutely correct. We were raised on those films.

DW: When you were beginning to make films, or before, what was your feeling about French and German filmmaking, for example?

ML: The truth of it is, historically, biographically, I was 17 in 1960 and it was that year that I left Manchester and came to London. Prior to that moment, I had virtually never seen a film that wasn’t in English. You didn’t see world cinema, you saw Hollywood movies and British movies. About the only film I recall having seen was Le Ballon rouge [1956], the sentimental French film.

However, when I hit London as a student in 1960, that is exactly the time of [Jean-Luc Godard’s] À bout de souffle [1960], John Cassavetes’ Shadows [1959], and the French New Wave, plus I discovered the rest of world cinema. What were my feelings about all that? I was completely blown away by everything. The most interesting answer to all that is to take note of the fact that this was also the time of the parallel British “New Wave.”

DW: Which I was going to ask about next.…

ML: The films of Tony Richardson, Karel Reisz, Lindsay Anderson and so on. Now, I personally felt that the purest, most important and most organic of those films wasn’t actually made till the late 1960s, and that was If... [1968]. And that was not a film about working class life, that was Lindsay digging into his own upper middle class, public school experience.

About the so-called British New Wave films…good as many of them were and inspirational as they were in some respects, because they were looking at working class life, the fact is that none of them, without exception, was an original movie, every one of them was an adaptation of a play or a book.

And although it’s historically true that [François Truffaut’s] Jules et Jim [1962] was an adaptation of a novel, nevertheless, the inspiration for me was that À bout de souffle, [Godard’s] Vivre sa vie [1962] and Truffaut’s Les Quatre cents coups [1959] were films that actually used film, like painting uses painting, to investigate something in a direct and original way.

DW: There’s no question that there is something to those British films of the early 1960s, but there are also problems.

ML: They’re script-bound. The truth of it is there was great integrity. You know, [Karel Reisz’s] Saturday Night and Sunday Morning [1960], [Tony Richardson’s] A Taste of Honey [1961], [Lindsay Anderson’s] This Sporting Life [1963], there was considerable seriousness and integrity, that’s not in question.

Curiously, and historically, and importantly, the first film that did what those films did was really outside the fold, it was Room at the Top [1959], directed by Jack Clayton. The real revolution, in a way—which I didn’t pick up at the time, because I didn’t watch television—was what [producer] Tony Garnett and Ken Loach did, which was to say, “Why don’t we get away from this terrible studio-bound convention of doing plays? Let’s get out on the streets with lightweight cameras, newsreel equipment,” like the French were doing, and that was the revolution, it was that that I joined in on a few years after it started. With Tony Garnett, he got me into the BBC.

DW: My concern at the time was a feeling that there was a certain occupational hazard in Britain, so to speak. To write and work in a country with such an immense literary tradition, Shakespeare, Dickens…it’s like having a very, very powerful father, and I felt there was a certain parochialism and insularity that went along with that. The kitchen sink drama seemed to me to be somewhat provincial.

ML: Yes, I agree. This goes back to something I said earlier. For me, the natural influences, really early influences, were not only movies, but theater, vaudeville, circus, pantomime, and the Marx Brothers, Chaplin, Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, The Three Stooges, Mickey Mouse and cartoons, and all the rest of it, those things were as important…and this is where I would differ from Ken Loach, Tony Garnett. Yes, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists [a classic of British working class literature published in 1914] is important, yes, Dickens is important, and, yes, there’s no question that a major influence is the time I spent as a youth in a socialist—a socialist-Zionist—but a socialist youth movement, and that’s all important too.

But the fact of the matter is that the heightened, theatrical, vaudeville aspect of what goes on in my films is as important as the hard, social way of looking at the real world. Those two elements are absolutely and mutually inseparable.

DW: To be blunt, I think that’s one of the elements that gives the film their particular quality, I think that is what distinguishes them.

ML: In Topsy-Turvy, it does the same thing, but in a topsy-turvy way. That is an apparently chocolate box subject, but what we’re actually looking at, in a hard and real way, is real people, doing real jobs, doing the very thing we’ve been talking about, taking seriously and rigorously the job of entertaining and amusing and otherwise stimulating other people.

DW: The films seem to begin less from a theme as a lump, but rather as an attitude toward a particular aspect of life, something you want to investigate.…

ML: I guess so, although I don’t know that I’d say “an attitude” toward an aspect of life, because what I’m trying to do is precisely, if possible, look at the world from a multi-perspective.

My natural instinct is to see people, to see society as society, but really as a society that works because of the nature of the individuality of individuals. I can’t look at a crowd without seeing a thousand individuals. What’s fascinating to me is that each of us is different. So in each of my films, each of the characters, large or small, is properly and organically and thoroughly, in a three-dimensional way, at the center of his or her universe.

So that therefore, by implication, even though there may be a clear objective or thing that I’m exploring, nevertheless, you get multi-perspective, because the characters, even though they might be subordinate, don’t become ciphers. They’re not non-people, the detail of everybody is the nature of what it’s about.

DW: Again, this is important, as opposed to much of what is unhappily called “political filmmaking,” these are genuinely spontaneously created human beings. And that’s not an easy thing to do.

ML: No, although, in my view, the films are entirely political and entirely concerned with investigating and reflecting on how we lead our lives. But I would challenge anybody to say that they’ve walked out of a film of mine with one single clear notion as to what I’m telling them to think, because that’s not what happens basically. I want you to walk away with things to argue about and ponder about and reflect on and procrastinate about and, you know, supply for yourselves.

DW: Presumably that’s connected to your own process, through which you are not simply passing on something pat or entirely solved.

ML: That’s true, although it’s important to draw distinctions.

DW: The artist makes judgments and makes decisions.

ML: And, not only do I consider it as my job, but as the stimulating experience of making art, that one does distill everything and arrives at a point where it’s clear what it is. It’s not simply a random collection of lazy stuff.

DW: Absolutely, and I suppose that’s what’s complicated and that’s what’s art. So the spectator leaves having felt or thought something he or she hadn’t felt or thought before.

ML: Yes, and the important thing is that the spectator walks away and the film carries on, that you take something with you.

DW: Yes, I wanted to ask about “realism,” not with capital R, but an interest in reality and life.

ML: I certainly would, for what it’s worth, and it’s not worth much, endorse the probably academic distinction between naturalism and realism. What I do is not naturalism, it’s not the replication of surface naturalism. I want to get to the essence of things, in a heightened and distilled way, so I certainly think it is realism.

DW: About your methods.…

ML: What we shoot is very precise, but really I make up the film as we go along. That’s preceded, however, by a long period, half a year these days, of working with the actors and everybody else to prepare them. I don’t have an idea and then talk to the actors. I never tell the actors anything, and they never know anything other than what their character would know. I collaborate with each actor individually first to create a character, and I put the characters together and gradually we build up a whole world through discussion and research and improvisation and we arrive at a three-dimensional world, implicit in which are the dynamics for the potential film.

Then I do a kind of structure. But the precise way in which the dialogue comes into existence scene by scene is to go to each location and improvise and, through rehearsal, to break it down and build it up and distill it and structure it into a very precisely scripted thing. But I don’t go away into a separate room and write a script, I do it through rehearsal. It does become very precise, down to the very last semicolon.

DW: That kind of process is very rare. To take months like that. The time and freedom.…

ML: These are low-budget films. The strict principle has always been to organize the budget so that that time is there, at whatever cost. So, for example, when I used to go and make films at the BBC, where the budget already existed, and the filming dates already existed before they knew what the film was, I would go in and the first thing I would do was sit down with whomever it was and say, “What do we pull out of the budget and put into extended rehearsals?” So, for example, no overseas locations, no helicopter shots, very limited crowds, no elaborate action vehicles, nothing is going to be blown up.

The most remarkable thing about Topsy-Turvy is that it was made for 10 million pounds, which, considering what you see on the screen, is extraordinary. But we had a six-month rehearsal, we did research; it’s about an imaginative use of money, and nobody’s ever done it and not got paid for it.

The point is, I can’t make films any other way. It’s not the matter of a choice, we have to do that, if we don’t do that, we can’t make the film.

DW: I think of Chaplin and how he stopped working on City Lights [1931] for several months.…

ML: But we should remember that his roots, his metabolism as a filmmaker, like [Buster] Keaton, like [D. W.] Griffith, [Louis] Feuillade, like everybody who made films before the talkies came in, were precisely in the philosophy that you could get out there and explore things, that you could get out of bed each day and you didn’t necessarily know what you were going to do next. It was all about using film to be thoroughly and properly creative.

DW: We have been living through difficult times for the past several decades, the cult of wealth and greed, with Reagan and Thatcher and all those who have come after them. The present economic crisis is going to put an end to that, one way or another, because you’re dealing with the destruction of myths about capitalism.

Can you imagine a different political situation, one of discontent, of upheavals…how would that, or would that, affect your own work?

ML: I suppose the answer to that, at a fundamental level—it’s a dodgy thing to discuss, because nothing is ever black and white—would have to be no. I think what I make films about is how we are, although it’s pompous to say, in a universal way. Although the milieu is always specific, the actual things that are on the go, at a fundamental level, are endemic to what human life is about.

Now, people talk about three of my films—Meantime [1984], Four Days in July [1985] and High Hopes [1988]—as a kind of anti-Thatcher trilogy. Four Days in July is a film about Northern Ireland.

Meantime was quite consciously directed toward what was happening, four years into Thatcher, but High Hopes—although the characters talk about Thatcher, they have a cat called Thatcher—was really about putting your money where your mouth is. Not to sit on the fence, and if you’re going to call yourself a socialist, what does that actually mean? Not just paying lip service to it. On one level, anyway, like a lot of my films it was also about having children and not having children, and all the rest of it. It’s also about class and materialism, and stuff.

People have said to me, “Ah!, Naked was a post-Thatcher film.” This is all nonsense. The correlation between the passing of Thatcher and Naked is virtually non-existent, if we’re going to be honest.

Now, you could say quite legitimately, and a faction on the hard left has said it.… I’ve been to screenings in London and Sydney where people stood up and harangued me, particularly when we did Meantime, basically for having the tools to make a film and not making a film about the manning of the barricades, not dealing with those issues. I accept the criticism because that is not what I’m concerned to do, I’m concerned to do other things.

Comes the turmoil, the revolution, whatever, for me, the job, in fundamental terms, would be—sure, to be taking the temperature, as I always do; sure, to be dealing in surface terms with the world that we’d be looking at—to look at people in terms of human needs, human behavior, and feelings and emotions, how men and women function, what it is to be a parent and child, how to survive.

Having said that, nothing makes sense to me except a world in which there is real equality. I can’t believe, for example, I live in a country where, after more than a decade of a so-called “socialist” government, we still have a railway system, an education system, a healthcare system, a steel industry which are riddled with the curse and disease of privatization. This is the only country in Europe where the railways are a complete mess.

DW: A final point. We know that no individual book or film changes the world, yet books and films do change the world. Do you have any thoughts about the relationship between art and social change, an indirect, complex, often subterranean, long-term relationship?

ML: Look, this goes back to something that we’ve been saying during this conversation. If I make films where people walk away with stuff on the go, if you tell me about the response of a teacher to Happy-Go-Lucky, I feel like I’m justified in thinking that, in some minuscule way, I’m making a contribution to that person’s life, or to individual people’s ideas.

I call my films subversive. I think it’s subversive to tell the truth about things, not the obvious political truths, and how people are. That’s what I do.