The last several weeks brought the news of the recent deaths, less than one month apart, of two vocal artists whose lives and careers were identified with the struggle against racial oppression. Born only 14 months apart, yet half a world away from one another, Miriam Makeba and Odetta came of age and achieved fame in the 1950s and 60s, a period of intense social and political struggles in both South Africa and the United States. Those struggles—their aspirations, triumphs, contradictions and limitations—found expression in their music and their lives.

Miriam Zenzi Makeba was born on March 4, 1932, in Prospect township, Johannesburg, South Africa. Her mother, a domestic worker and sangoma (traditional healer), was from the Swazi tribe. Her father, a Xhosa, died when she was six. Both languages would be among the several included in Makeba's musical repertoire.

The Johannesburg in which Makeba grew up was a musical cauldron in which urban black musicians adapted tribal rhythms and melodies to European instruments. At the same time, they were attracted to other styles, particularly American popular music. They fused the techniques and styles of performers like Louis Armstrong, the Ink Spots and Ella Fitzgerald—and later, bebop stylings—with their own indigenous music to produce unique hybrid sounds.

In this milieu, Makeba developed the fluid phrasing, rhythmic propulsion and charismatic stage presence that would make her famous. She performed with several groups and recorded extensively, yet with little recompense, due to the exploitive and racist practices of South African record companies.

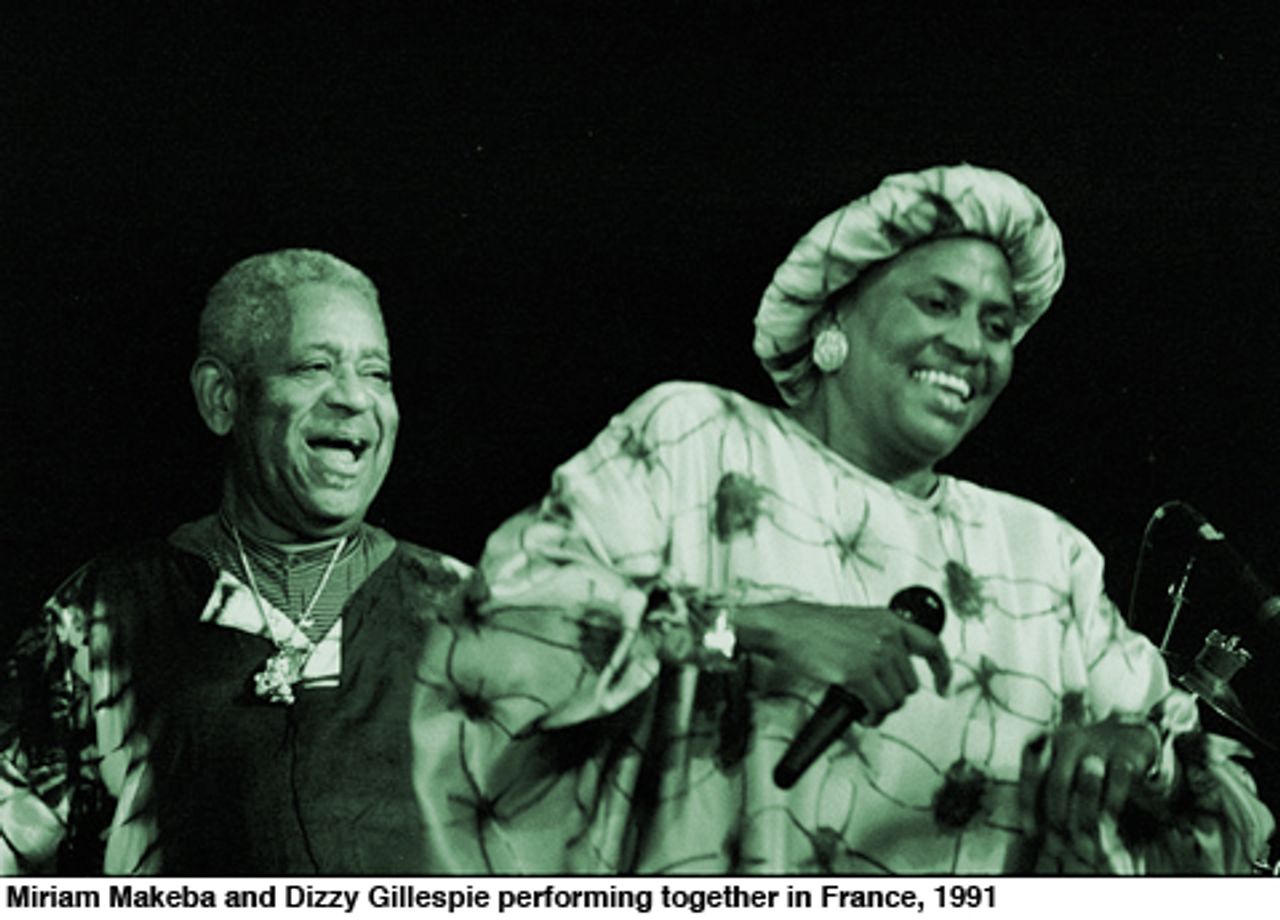

After performing in a musical in 1959 with her future third husband, trumpet great Hugh Masekela, she starred in an anti-apartheid documentary in the same year, and traveled to the Venice Film Festival to attend the premiere. She then went to London, where she met calypso singer Harry Belafonte, who proved crucial to her career, encouraging her and helping her establish herself.

When she attempted to return to attend her mother's funeral in 1960, Makeba found that her passport had been revoked. She lost her citizenship in 1963 after testifying at the UN against apartheid. Her records were banned in South Africa as well.

Her career flourished, however. Under Belafonte's tutelage, she performed and recorded in the US and Europe, and on the African continent as well. Among her best-known numbers were "Pata Pata" and "Qongqothwane"—known popularly as "The Click Song"—sung in Xhosa, a language distinguished by its dental, lateral and palatal "clicks." Another favorite was the Swahili tune "Malaika."

Makeba's life had its share of personal challenges and tragedies in addition to the grim reality of apartheid. Her first husband was violently abusive, and deserted her after she fought and defeated breast cancer as a young adult. She lost family and friends in the Sharpeville massacre and other cases of savage repression by the apartheid regime. When she married her fourth husband, American black nationalist Stokely Carmichael (who later changed his name to Kwame Toure), the recording and performing gigs dried up in the US and in Europe as well.

Makeba's life had its share of personal challenges and tragedies in addition to the grim reality of apartheid. Her first husband was violently abusive, and deserted her after she fought and defeated breast cancer as a young adult. She lost family and friends in the Sharpeville massacre and other cases of savage repression by the apartheid regime. When she married her fourth husband, American black nationalist Stokely Carmichael (who later changed his name to Kwame Toure), the recording and performing gigs dried up in the US and in Europe as well.

She was exiled from South Africa for 30 years, only returning in 1990 after apartheid had been officially dismantled. The 1985 death of her only daughter, Bongi, herself a formidable talent, plunged Makeba into a period of "spiritual madness," as she called it, from which her recovery was slow. Toward the end of her life, she suffered from serious disabilities.

Nonetheless, she continued to tour and sing, despite declaring her impending retirement more than once. At one point, she famously conceded, "I will sing until the last day of my life." In fact, she suffered cardiac arrest on November 10, collapsing as she was leaving the stage after singing at a concert in Italy to support an Italian writer who had been threatened by local organized crime.

By the time of her death, Miriam Makeba had received numerous awards. Regularly referred to as an icon and a symbol of the anti-apartheid struggle, she was known to many of her fans as "Mama Africa." As this nickname suggests, Makeba's life and career were bound up with the nationalist limitations of the South African struggle.

Under the leadership of the bourgeois nationalist African National Congress, that struggle ended with the incorporation of a layer of blacks into the South African ruling class, while the conditions of life for the vast majority have not improved at all. Makeba, who spoke out courageously against oppression, later allowed her name to be associated with post-colonial strongmen and dictators—mislabeled "Marxist" and "socialist" in the bourgeois media—in Guinea, Togo and Ivory Coast.

Odetta Holmes was born December 31, 1930 in Alabama, but moved to Los Angeles as a young girl. Like Makeba, her father died when she was young, and also like the South African, she grew up in a musical melting pot. Musically, Los Angeles in the 1940s was a swinging place. Blacks who had migrated from the South to seek work in wartime industries could go to the fabled Central Avenue clubs to hear not only touring jazz, blues and popular artists, but the abundant local talent as well.

On the other hand, the black population still faced racism and discrimination. The police force in Los Angeles was notorious for the brutal treatment of blacks who had the misfortune to find themselves in its custody.

It wasn't to jazz that Odetta's early musical direction turned. A high school teacher heard her in glee club and urged her to study classical singing, with the idea that she could follow in the footsteps of Marian Anderson, the famous black classical contralto. Odetta studied and developed the powerful voice and technique that astounded and delighted listeners and stayed strong to the end.

Her classical aspirations were sidetracked, not only by her doubts that she could become another Anderson, but also by her exposure to folk music in the coffee shops she haunted while a member of an acting troupe in San Francisco. Taking up the guitar, she immersed herself in the music of the poor and oppressed she heard performed live, or off folk anthology recordings: songs of slaves, sharecroppers, convicts, struggling workers (and of course, jilted lovers). She told an interviewer in 2005 that folk music reflected the "fury and frustration" over the racism she saw and experienced as a girl in the South and growing up in Los Angeles.

With spare accompaniment, Odetta treated seemingly simple songs like "Water Boy," "This Little Light of Mine" and "Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child" to a full range of expressive vocal techniques: growls, chokes, melisma, rhythmic and dynamic shifts. When she moved to New York in 1953 she became a part of its thriving folk music scene, and was soon regularly performing and recording her repertoire of blues, spirituals, work songs and ballads.

By the early 1960s, the civil rights movement had entered its period of greatest militancy, and Odetta lent her services to marches, rallies and other events. Her talents were put to use by the official leadership of the movement. At the August 28, 1963 March on Washington, her rendition of "I'm On My Way" thrilled the assembled hundreds of thousands.

By the early 1960s, the civil rights movement had entered its period of greatest militancy, and Odetta lent her services to marches, rallies and other events. Her talents were put to use by the official leadership of the movement. At the August 28, 1963 March on Washington, her rendition of "I'm On My Way" thrilled the assembled hundreds of thousands.

The later decades of Odetta's life and career reflected the decline of the civil rights movement with which she had been so closely associated. Certain limited reforms were won in the form of the civil rights legislation of the mid-1960s. These measures left capitalist property relations untouched, and laid bare the fundamental class issues in American society, as poverty and social polarization continued to plague African-American and other working class communities.

The social and political changes meant a decline in appearances and recording opportunities for Odetta, and this was also true of the folk music revival of which she had been a part.

Odetta's old recordings continued to inspire budding folk musicians, however. She was held in the highest regard for the integrity and consistency of her contributions to musical life. Taking her career as a whole, she has been cited as a major influence on such artists as Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Janis Joplin and Harry Belafonte, who collaborated with her on an album in 1961.

After a decades-long dry spell, Odetta returned to performing and recording regularly in 1998. She continued working, despite longstanding heart disease, until the end of her life, including 60 concerts in the last two years. Her health declined in November, and on December 2, less than a month before her 78th birthday, she died in New York City.

Like Miriam Makeba, Odetta's final years were marked by official recognition and honors. Again, however, as with Makeba, Odetta was turned into a kind of icon to celebrate civil rights reforms. On the part of the cultural and political establishment, such efforts have as their aim covering up the explosive, and even revolutionary, potential of past struggles and the lessons to be drawn from their outcome.

Odetta, like most of her generation, was not able to grasp the lessons of the experiences through which she and others had passed. She gratefully accepted a National Endowment of the Arts medal from President Bill Clinton in 1999 and expressed the wish, in the days after this year's election, to sing at Barack Obama's inauguration in January.

Notwithstanding these historical limitations, the songs of Miriam Makeba and Odetta—songs of suffering and struggle, but also of joy and the vision of a world of genuine equality—are a legacy that will continue to move future generations who take up the battle to finally achieve the goals that inspired their predecessors.

See and hear Miriam and Bongi Makeba here.

The New York Times interview of Odetta, with archival footage, is here.