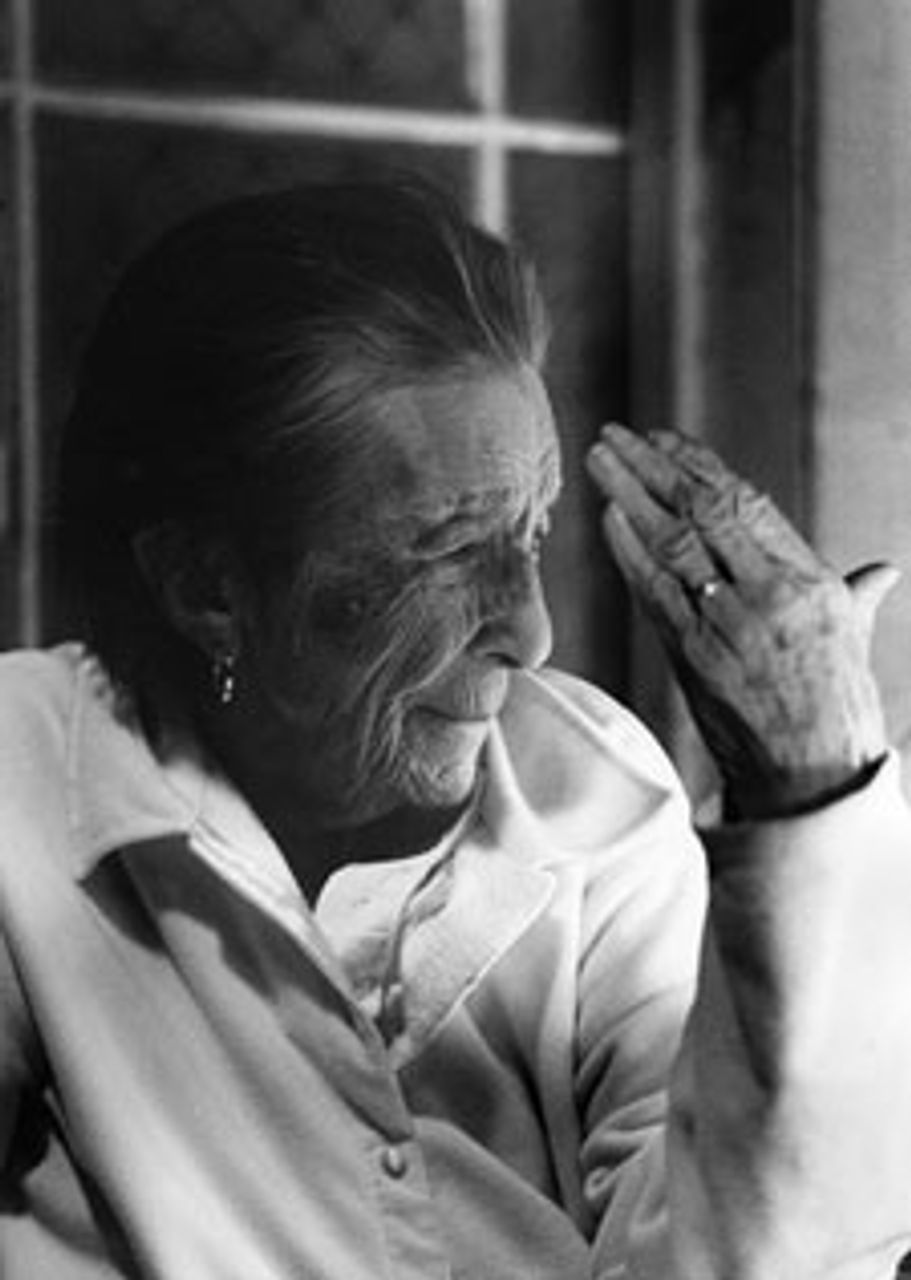

Louise Bourgeois, 2003

Louise Bourgeois, 2003Photo: Nanda Lanfranco

On 25 December the artist Louise Bourgeois celebrated her 97th birthday. During her lifetime Bourgeois has produced a significant body of work in a personal visual language, which, nonetheless, has been fundamentally shaped by the tumultuous events of the 20th century.

The past year has seen renewed interest in Bourgeois and her art. New York's Guggenheim Museum, London's Tate Modern and the Centre Pompidou in Paris hosted a comprehensive exhibition of her work—the first major retrospective since the early 1980s, followed by the release of a new biographical documentary.

Bourgeois's most important work is dominated by images of crippling fear, the tortured, ghosts of the dead, somber darkness, paralyzing mental illness—all representing attempts to explore the source of these emotions and find normality under extreme conditions. Most commentaries, including the exhibition catalogue, tend to link Bourgeois's work merely to her introspective nature or personal psychological traumas. Few treat seriously the impact and influence on the artist of objective historical and social conditions and the intellectual climate they generate.

Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911 and spent her childhood in a large household partly used for the family business of restoring antique tapestries. Her mother taught her drawing, the use of color and a vast array of tapestry styles. Bourgeois describes socialism and anti-clericalism as a part of family life. Her mother's heroes included the brilliant Marxist Rosa Luxemburg and anarchist Louise Michel (a participant in the Paris Commune) and her father and grandfather were sympathizers of the anarchist thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

The pre-World War I idyll that Bourgeois describes as the font of much of her work was shattered in the first week of hostilities, following the death of her uncle who had enlisted in the French army. Her father, himself twice wounded, never recovered from this loss. One of Bourgeois's earliest memories is of traveling as a very small child with her mother to different military hospitals and seeing "whole trains filled with people wounded at the front and [how] you would hear them in the night."

The horrors of war continued to haunt Bourgeois. She describes entering a staff canteen beneath the Louvre museum in 1930 where she worked as a guide—a prestigious job obtained by her astonishing grasp of art history—to find "a hell of people with amputated limbs, people who have been wounded in the war. If you are wounded in France you are entitled to an official position. I'm talking seriously now. And I walk in and look and a leg is cut off or an arm is gone, and they are in that basement eating their lunch. And I had such revulsion, such revulsion." (Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews 1923-1997, edited and with texts by Marie-Laure Bernadac and Hans-Ulrich Obrist. Violette Editions: London, 2000, p.154.)

These traumatic experiences profoundly shaped both Bourgeois's life and her visual language—limbless bodies and bodiless limbs are a constant presence in her work from the early "Femme Maison" series, through "Arch of Hysteria" (1993) and "Spiral Woman" (2003) to her later "Cell" series.

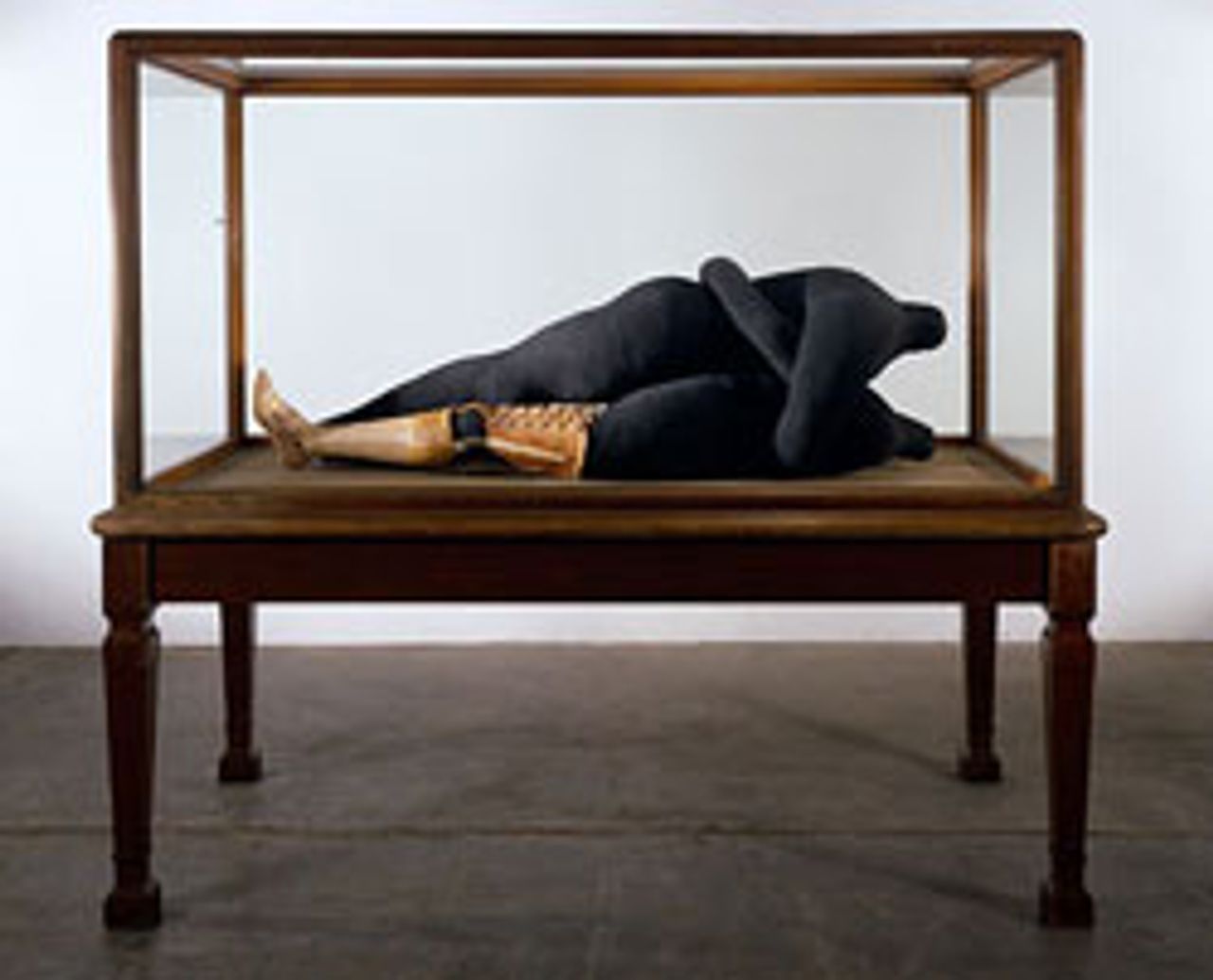

CELL (CHOISY), 1990-93

CELL (CHOISY), 1990-93Collection Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Toronto

Photo: Marcus Leith

Bourgeois was not part of the generation that, as young adults, directly experienced or lived through the First World War, the 1917 October Revolution in Russia or the revolutionary wave of 1917-1923. She was part of the next generation, attracted to Marxism in the early 1930s. By this time the degeneration of the Soviet Union and the Communist International under the Stalinist dictatorship was very far advanced.

Bourgeois moved to the left and saw her work recognized at a very difficult time: the Nazis seized power in Germany in 1933, and the Stalinists created a cultural concentration camp in the Soviet Union, undertook the Moscow Trials 1936-1938 and consciously betrayed, along with the social democrats, the revolutionary situation in France. The great disappointment of these years had an enormous and dispiriting effect on the most thoughtful and serious artists.

Bourgeois was serious enough about politics and art, particularly constructivism, which she first encountered at an exhibition in Paris in 1925, to take time out from her mathematics and philosophy studies at the Sorbonne to travel to the USSR twice, the first time in 1932. Her second visit was in 1934—the year the Soviet writers' congress codified the stamping out of cultural groups and adopted deadly "socialist realism" as the official aesthetic.

It is impossible not to see these facts as significant even though Bourgeois has written remarkably little about them. She downplays her time in the Soviet Union saying, "I did some posters for [influential poster and stage designer] Paul Colin, and I made some posters that were sympathetic to the Russian regime. I went there with some of my posters and had them shown in Moscow."

As for Marxism, Bourgeois claims she only became interested "because it bothered my father." Such comments, if they are honest, only underscore that she has a limited understanding of her own development. The Tate Modern exhibition catalogue points out that she oriented towards Communism, but never absorbed revolutionary Marxist ideology. This is no doubt true, but what needs adding is the fact that she was not going to receive a Marxist education either through the French Communist party or the Soviet Stalinist officials she encountered. In other words, there were tremendous obstacles placed in the path of her generation acquiring a systematic understanding of genuine Marxism.

In 1934, Bourgeois returned to France where she says she intended to publish an article about her experiences in the Soviet Union. (I have been unable to locate it.) In fact, her published writings and interviews only begin in 1938, although she kept a diary from 1923 onwards.

Leon Trotsky also arrived in France in 1934—as a political exile from the Soviet Union. Although the majority of the French intellectual left remained silent or defended Stalin's crimes, Trotsky was able to discuss with those honorable exceptions who opposed Stalinism, including many of the important artists and writers who influenced Bourgeois. Foremost amongst those was the surrealist poet André Breton, above whose Gradiva gallery Bourgeois lived for a time.

In the following years Bourgeois worked closely with artists such as Othon Friesz, Roger Bissière and Charles Despiau, former assistant to Auguste Rodin. She describes learning from Fernand Léger, the brilliant interpreter of cubism, how to express human emotions with minimal use of line in her painting and how, recognizing her interest in three-dimensional form, he urged her to take up sculpture. She would later explain, "I could not be a painter. The two dimensions do not satisfy me. I have to have the reality given by the third dimension."

In 1939 Bourgeois emigrated to the US with her new husband, the art historian Robert Goldwater, an expert in primitive art and first director of New York City's Museum of Primitive Art in 1957. He assisted and befriended many of the significant artists driven into exile by the Nazis, such as Breton, Max Ernst and Giorgio de Chirico, but Bourgeois's renewed acquaintance with them seems to have been a demoralizing experience. She criticised what she called their grand manner, male chauvinism and "success," but, more fundamentally, she was also witness to the increasing political and artistic disillusionment with revolutionary ideas of many of the exiles.

On 10 May 1940, Hitler unleashed the Nazi blitzkrieg. The French army rapidly collapsed, and a Vichy puppet government was installed, welcomed by significant sections of the French ruling elite. Bourgeois's older brother Pierre, who had enlisted in the French army, suffered so much from shell shock that he spent the rest of his life in and out of institutions. Bourgeois explains how these terrible events affected her art: "My relation to the war appears in the work by the use of black, the black of the war, which was the black of mourning.... What the war meant to me was that suddenly, and this was documented by dozens of drawings, I saw everything in black, black coffins, black legs, black people. It was the deep mourning of the war, it is as simple as that."

Bourgeois joined the New York Students Art League, befriending artists who became leading figures of the abstract expressionist school, including Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell.

The initial euphoria that greeted the collapse of the Nazi dictatorship and the fall of Vichy France was quickly dissipated. To horror at the revelations of the Holocaust was added horror over the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japanese cities and the brutal face of post-war American imperialism, both at home and abroad.

The disillusioned retreat from active participation in politics was summed up in the comment by Motherwell and fellow artist Ad Reinhardt in 1947: "Political commitment in our times means logically—no art, no literature." Bourgeois showed some sympathy for the abstract expressionists and their turn to "universal myths" and, obviously, abstraction, although she never attached herself formally to any artistic school nor abandoned the representation of recognizable human dramas.

Bourgeois was also attracted to the politics of the American journal Partisan Review, calling it "our bible." Trotsky had hoped the magazine, first published in 1934, would "take its place in the victorious army of socialism." In a brilliant article he penned for it in 1938, "Art and Politics in Our Epoch", Trotsky stressed the "burning need" for a "liberating art" made by artists rejecting "orders from outside" and "heaping scorn on all who submit to them." Essential in this struggle, he explained, was the exposure of the counter-revolutionary role of Stalinism.

By the time Bourgeois embraced Partisan Review, however, it was safely on its way into the orbit of liberalism and anti-communism, along with wide layers of the American "left" intelligentsia.

In an Art Journal interview in 1994, Bourgeois described to Anne Gibson how she still remembered Lillian Hellman as one "who retained her Communist views," and Breton and art critic-historian Meyer Schapiro as Trotskyists, but according to Gibson she refused to identify herself as explicitly "right" or "left" herself. As Bourgeois told Gibson, "Politics is a very dangerous subject. Always was, always will be." Bourgeois explained how she saw the period as one "without feet...not grounded.... Things expressed a great fragility and uncertainty. ... If I pushed them, they would have fallen." To separate this kind of sentiment from her art work, as most commentators do, is ultimately self-defeating.

Bourgeois reflects on the post-war situation in a number of memorable works. For her first solo exhibition she completed the "Femme Maison" series (1945-1947) and "Fallen Women (Femme Maison)" (1946-1947), the culmination of a series of drawings begun in 1942, using the surrealist technique of merging or juxtaposing contradictory objects. They show the female body fused with house-like structures, desperately trying to outgrow the house, but at the same time trapped within it. These works reveal Bourgeois's role as a member of a pioneering generation of women who broke down many of the barriers in the overwhelmingly masculine artistic circles of the time. Also, on a deeper level, these works express her sense of frustration and, I would argue, feelings of destructive impotence in the face of the menace of fascism and war.

"He disappeared into complete silence" is a series of nine engravings accompanied by descriptive texts from 1946 that may have their origin in the Museum of Modern Art program Bourgeois participated in during the war that used art to assist in the rehabilitation of American soldiers.

One plate that stands out for me is "No Entrance, No Exit", which depicts a bare room with a single window, beyond which is a formless empty space. Four floating ladders press against the roof. There is no way in and no way out. The accompanying text states, "Once an American man who had been in the army for three years became sick in one ear. His middle ear became almost hard. Through the bone of the skull back of the said ear a passage was bored. From then on he heard the voice of his friend twice, first in a high pitch and then in a low pitch. Later on the middle ear grew completely hard and he became cut off from part of the world."

THE BLIND LEADING THE BLIND, 1947-1949

THE BLIND LEADING THE BLIND, 1947-1949Courtesy Cheim & Read, Galerie Karsten

Greve, and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Christopher Burke

"The Blind Leading the Blind" (1947) consists of a series of regimented wooden legs reducing to a point held together by a piece of wood across the top. Bourgeois locates the source of the image in a childhood memory linked to hiding under the kitchen table and seeing her parents' legs crisscrossing with the table legs while they prepared a meal, "What are they doing? What is their game? What is their purpose? How do I relate to them? And in the end I considered that they were not friendly, I decided that the outside was not friendly."

As Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond point out in European and American Paintings and Sculptures 1870-1970 in the Australian National Gallery, Bourgeois made the sculpture at the height of the Cold War and the title refers to the New Testament verse (Matthew 15:14), "If the blind lead the blind, both shall fall into the ditch." It is an effort, the authors suggest, to portray "‘catastrophe,' ‘a chain of pain,' ‘people fated to be destroyed together.'"

Also in 1947, Bourgeois created her series of wooden and metal sculptures "Personages", depicting emotive totem-like structures that taper down to a delicate unstable point, whilst appearing to lean on one another for support. According to Bourgeois, they are images of friends and family, particularly her brother, whom she had left behind in France, explaining them as "a recreation of people I missed...even though the shapes are abstract they represent people."

At the same time, they could also be survivors of the Holocaust emerging from the camps or the traumatized civilians emerging from the rubble of European cities destroyed by nearly six years of war. They are not only an indictment of the war, but also the ability of humanity to resist its impact. I think they are truly noble figures.

Bourgeois, to her credit, tried to defend artistic freedom under the difficult conditions of the anti-communist witch-hunts and McCarthyism. In 1950 she signed a letter of protest by eighteen artists known as "the Irascibles" against the choice of conservative works displayed in a Metropolitan Museum exhibition.

After applying for citizenship in 1950, Bourgeois came under investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee. She explained the "different fates" awaiting her and fellow artists saying, "[Marcel] Duchamp had powerful friends, so he was safe. [Amédée] Ozenfant was a very awkward person, original and independent. When he was attacked he would attack back like a child. So he was kicked out of the country. But I defended myself. I was interrogated several times after I made an application to become a citizen. My defense was that I had no connection with or knowledge of what the men I was involved with were doing politically."

For me, this statement reveals in a subtle way how the pressure of events and not some personal artistic or moral weakness was driving Bourgeois away from social life and in a far more inward-looking, purely subjective direction.

For many years after she retreated from public life in an attempt to create the best conditions to work without facing official vilification. By the time Bourgeois was finally given citizenship in 1955, she clearly defined herself, like many others of her generation, as an existentialist. She absorbed the works of Jean-Paul Sartre and made a point of meeting Albert Camus, whose books influenced her own writings, particularly the puritan. Camus famously said at one point that after the dramatic upheavals of the previous period (in which he participated), he was "tired of the struggle," and as a result only the moral protests of individuals were possible.

Bourgeois reflects this despairing view writing in her diary, "Tension with neck ache, revolt, work, rage—no sleep. Depression—no pain—no work—no fight—no hope—no interest in work—or appearance."

Typical of her work in this period is "Forêt" (Night Garden) (1953), which represents a collection of dark huddled figures greeting each other as if survivors of a terrible trauma. The relationship between each form is sensitive and the impression it leaves is of a group of outcasts seeking solace from a hostile world in each other's company.

Another is a written text from the early 1960s, "View from the Bottom of the Well," only published in 1996 with a series of nine etchings. Bourgeois wrote in the text at the time: "I cannot concentrate because I just hate it, anywhere but here. Is it fear? Fear of what? I am not actively or passively fearful, I am as tight as a knot and as hard as stone. I know enough not to talk. What for? Talk at the antipodes of what I want? No thank you. The humming bird is my friend. I am a humming bird."

After recovering from a nervous breakdown in 1966, Bourgeois studied the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), whose ideas Sartre considered as a precursor to existentialism, and was deeply moved by his concept of anxiety and anguish. In his own time, Kierkegaard's views expressed a lack of confidence in science and reason as the guarantor of human progress and a descent into cynicism and mysticism, although Bourgeois formally rejected his reactionary religious conclusions.

I believe such anti-materialist statements by Kierkegaard as "People generally believe that the tendency of a person's thoughts is determined by external circumstances.... But this is not so. That which determines the tendency of a person's thoughts is essentially to be found within the person's own self" found a ready audience in artists like Bourgeois who had witnessed the Stalinist distortion of Marxist philosophy and experienced a general disappointment with history, society and the project of social change. Something similar could be said about Bourgeois's study of the psychology of art, in the course of which she explored neo-Freudian art criticism and its arguments that artistic creativity ultimately has its origin in sexual feelings and not in social relations.

In the late 1960s, the post-war boom broke down, and Bourgeois once again witnessed the eruption of a new wave of revolutionary struggles by the working class (1968-1975) and the collapse of a number of dictatorships. She was not prepared for this new period and turned to identity politics. Having distanced herself from socialism or left-wing thought over the previous period in the America of the post-war boom and Cold War, Bourgeois was unable to resist these pressures and gravitated towards "alternative" politics based on gender. She was undoubtedly part of a pioneering generation of women who broke down many barriers, but I believe her turn to feminism seriously affected her ability to approach reality in all its richness. Typical works of the period are "Sleep II" (1967) and "Fillette" (1968), which depict violent treatment of the male sexual organ.

Other works of the period reflect Bourgeois's profound sympathy for the civil rights and anti-war movements, such as "Noir Veine" (1968) and "Colonnata" (1968). They are dominated by the color black and show dark figures moving carefully, but firmly, towards an unseen enemy and seem to express her solidarity with the civil rights marchers and those dying in the Vietnam War. "Rabbit" (1970) shows an innocent rabbit hung upside down and split down the middle with its internal organs carefully displayed. Does this represent what the US military was doing to the Vietnamese? Or does it show what Vietnam revealed about American society?

In 1970 Bourgeois participated in the campaign to defend the Judson Three, arrested and charged with exhibiting the work of anti-war artist Marc Morrell, including one notorious piece "desecrating" the US flag. Bourgeois wrote letters of appeal and donated works of art to their defense fund.

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE FATHER, 1974

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE FATHER, 1974Courtesy Cheim & Read, Galerie Karsten Greve, and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Rafael Lobato

One of her major works from the end of this period is "Destruction of the Father" (1974), depicting a cave-like structure in which primitively-shaped rock-like figures surround a sacrificial slab, observing with a cold indifference the severed body parts scattered across it (real joints of lamb bought at a local butcher's shop). It is a very disturbing work, which is reminiscent of the work of one of Bourgeois's favorite artists, the 18th century Spaniard Francisco Goya.

Bourgeois describes the scene as a family tearing limb from limb the domineering patriarchal father figure, but it is difficult not to view the use of dead lambs as highly symbolic, referring perhaps to the young soldiers dead or dying on the battlefields of Vietnam or Verdun. Bourgeois's visual references to past representations of war are very rich and deserve much more serious attention.

The upheavals of the late 1960s and early 1970s were suppressed with the assistance of the Stalinist and social democratic parties, setting the stage for a counter-attack by the ruling elite identified with the figures of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in particular. Bourgeois was sensitive to the class tensions that this new period ushered in. It also marked the beginning of her institutional recognition, culminating in President Bill Clinton presenting her with the National Medal of Arts at the White House in 1997. Bourgeois expressed surprise at this turn of events, although she appears to have seized it with both hands.

In 1978 Bourgeois produced a stencil rubbing series entitled "The Whitney Murders," which described her disgust at the cold political and market-driven process behind the production of art, the selection of a few favored artists and casting aside the others. She explains: "I resented so much the whole thing because I was not in. You see? That I was ready to murder everybody, right."

In 1982 Bourgeois wrote a text in Artforum entitled "Child Abuse" in which she defines her artistic conceptions almost entirely within the framework of childhood traumas. However, barely concealed behind the neo-Freudian categories is the weight of a past full of experiences she finds almost unbearable: "[S]ome of us are so obsessed with the past that we die of it.... It is that the past for certain people has such a hold and such a beautys.... Everyday you have to abandon your past or accept it and then if you can't you become a sculptor."

Illustrative of this period is a remarkable marble sculpture "Femme Maison" (1983). A seated female form can be made out beneath a shroud; once again the head resembles a building structure. The form is more resigned than the struggling trapped figure in the first "Femme Maison" series. In her "Femme Maison" of 1994 this air of resignation becomes more pronounced, with a female form lying on her back without arms, her head merged with a house that has a small door.

Bourgeois, now in her seventies, was the subject of renewed interest. On the one hand, various academic trends hailed her because of her existentialism and feminism, describing her work as a free-floating art of the psyche detached from the objective world. On the other hand, young artists interested in her life and work became drawn to her artistic independence, intensity, exploration of a vast array of artistic styles, references to artistic history and sensitivity to social questions.

There is a series of sculptures from 1989-1990 that I believe are very important, depicting small limbs appearing in states of submission or distress. "Décontractée" (Relaxed) has two small hands laid palms upward on a large piece of stone-like material. "Untitled (with Foot)" (1989) presents a small child's leg carved with an almost unique emotional sensitivity crushed beneath a large round earth-like object. Here there is an echo of the first "Femme Maison" series, but also substantial differences. The objects involved are child-like limbs, not the whole bodies of women. The sculptures have a simplicity of imagery that suggest they have sprung fully formed from the unconscious, but perhaps they represent images of the laying to rest of her youthful idealism.

During the 1990s Bourgeois remained sensitive to the social chasm opened up between masses of people and the newly emerging super-rich. In a 1995 interview, discussing her use of water in her work, she explained, "When you hear about floods in California, the people who are flooded out are never the ones who live in the mountains. The mountains belong to the rich. There's no danger. It's always the housing projects where the poor people live that get flooded."

Bourgeois's remarks were made during the emergence of a new, more direct form of visual language: her "Cell" period. One of Bourgeois's intentions is the creation of self-contained environments you can walk into detached from the museum environment. They are remarkable constructions, which Bourgeois says is a way of isolating a past experience and then performing an "exorcism."

"Red Room (Child)" (1994) is an intense recreation of the dyeing room from her parent's tapestry business and also her husband's favorite room. It is constructed of a circular wall made up of old wooden doors, cotton bobs of different sizes displayed on stands, while a group of red hands clasp each other quite desperately. Elsewhere a large arm protects a smaller arm, a small white deer's head with a broken ear rests on a top shelf and a pair of white cloth gloves with "Moi Toi" (Me/you) written on them carefully lies on another shelf.

The huge "Dangerous Passageway" really speaks for itself, indicating that Bourgeois views her life experience as a constant series of threats to be maneuvered around and survived. There is a long passageway that looks like a prison gangway, on each side are prison cells containing family scenarios, images from the past, torture devices. In the corridor a dark shape hangs from the ceiling. In "Cell (Choisy)" (1990-1993) a cage containing a nightmarish marble sculpture of the family home is threatened by a guillotine.

COUPLE IV, 1997

COUPLE IV, 1997Courtesy Cheim & Read, Galerie Karsten

Greve, and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Christopher Burke

Bourgeois's more recent works include a series of fabric heads and figures in varying states of anguish and despair. In "Couple IV" (1997), what looks like an old wood and glass display cabinet from a provincial museum displays two headless fabric bodies attempting to make love, but there is an emotional distance between the two. Bourgeois explains this piece as her confusion as a child after accidentally witnessing her parents making love, but the overriding sensation is of failure in general.

Unlike, for instance, Michelangelo's "Slave" series or Goya's "Three Prisoners", the majority of Bourgeois's fabric figures and couples show not a struggle against their enslavement, but convey a sense of defeat and resignation. The ultimate responsibility for such an artistic conclusion lies with the traumas and disappointments of the 20th century. Bourgeois remains a remarkable figure at 97; it will be interesting to see whether time remains for her to respond to the current economic breakdown and the inevitable re-emergence of social struggle.