The lockout of nearly 600 miners at the Rio Tinto Borax mine in Boron, California, has entered its fourth week, with the multinational mining giant pressing ahead with its demands to gut wages, benefits, seniority rights and working conditions.

As their struggle escalates, miners would be well advised to draw the political lessons from their previous struggles, including the 1974 strike, when the small mining town in the Mojave Desert was the scene of a bitter class battle.

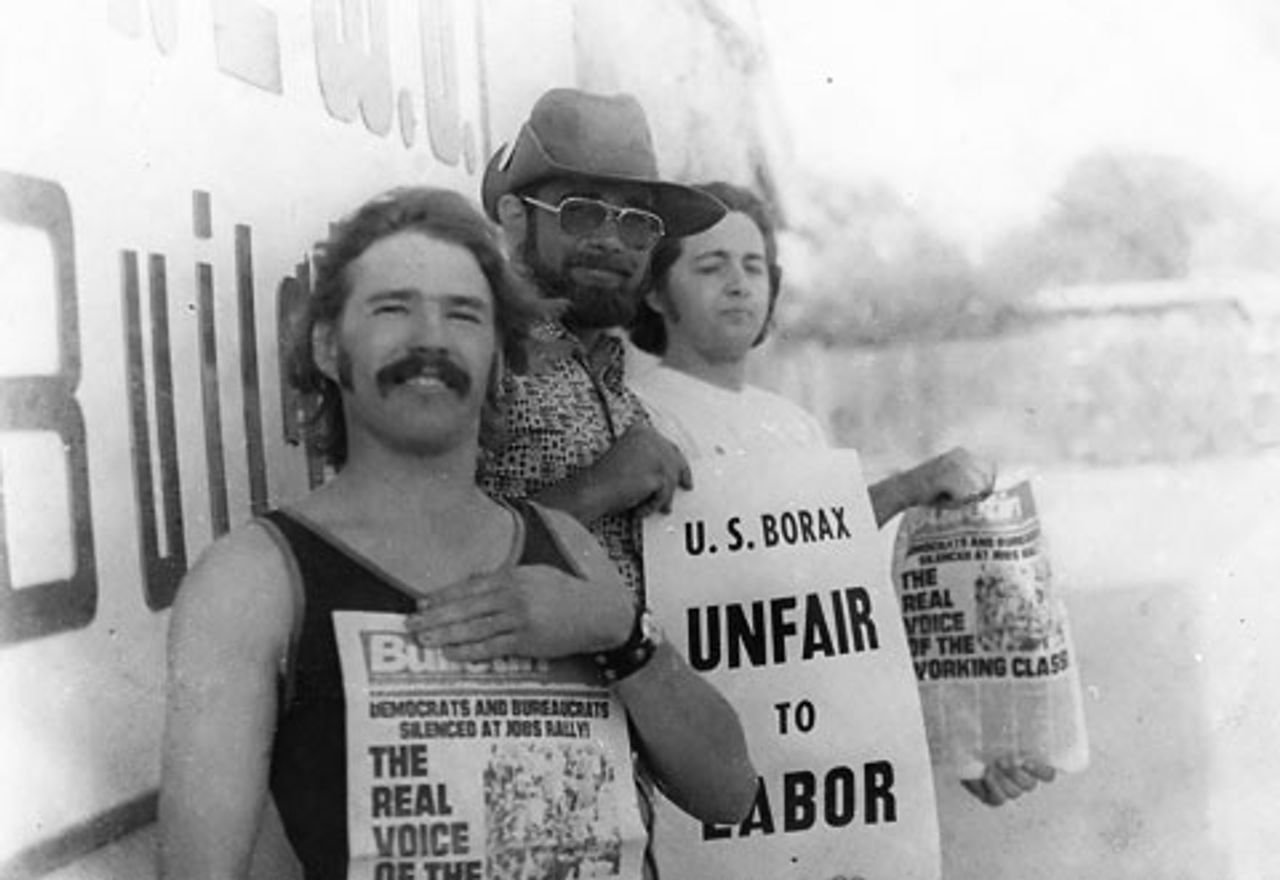

Borax strikers speak to Bulletin reporters in 1974

Borax strikers speak to Bulletin reporters in 1974At the time, The Bulletin, the twice-weekly newspaper of the Workers League, the forerunner of the Socialist Equality Party, widely covered the events and explained their significance for the entire working class.

For nearly five months, almost 900 miners struck for what today is almost incomprehensible—a 25 percent wage increase and a one-year contract. The company was then known as US Borax and Chemical Corporation, although Rio Tinto had purchased it in 1968.

From day one of the strike it was clear the company was carrying out a major union-busting assault. Fighting broke out the first night between 500 striking picketers and Kern County Sheriff’s deputies and security police when the company opened the plant gates and brought in pickup trucks filled with strikebreakers and guards. When the strikers stormed the plant gates to try to stop the scabs, police helicopters were brought in.

Before the night was over, over 100 police in full riot gear and two helicopters were patrolling the picket line. The union was hit with an injunction hours after the strike began, limiting the strikers to two pickets at the huge facility. But this did not stop dozens of strikers, who gathered daily across the road.

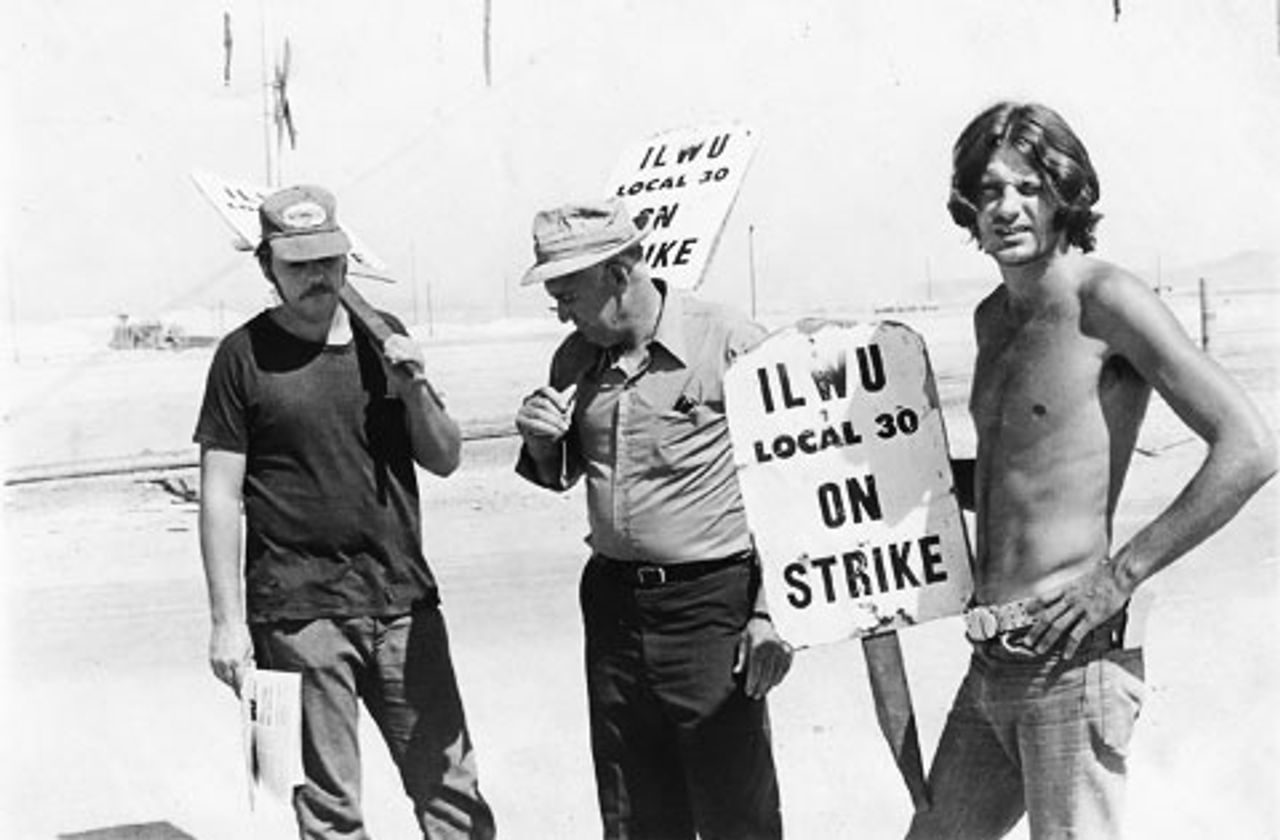

Borax strikers in 1974

Borax strikers in 1974The company approached the strike like a military operation. Ads posted in unemployment centers in the Los Angeles area seeking recruits to break the strike read, “Prefer veteran with combat experience or ex-police officer.”

Gene Pope, a striker, likened the situation to his military experience in Southeast Asia, “This is like a controlled Vietnam. As I saw the Vietnam situation, it was the government sponsoring violence for the subjugation of the workers and the peasants. Now they’re trying to do the same thing to union people. There is no doubt in our mind that they want to break this union.”

The militancy of the strikers was so great that private security guards had to remain inside the plant for 30 days at a time.

US Borax officials received support from then-California Governor Ronald Reagan, who instructed the sheriffs to step up their actions against the strikers. Before becoming governor, Reagan had been the narrator for the TV series, “Death Valley Days,” sponsored by US Borax.

During the third month of the strike, the small town was virtually occupied by the police for two days, setting up roadblocks, stopping strikers and their families.

Through the course of the strike, 110 union members were arrested. Many were shot at and severely beaten, including Kay Barlow, six months pregnant, who was beaten in the stomach with a billy club causing her to lose her baby.

In October 1974 the miners were forced to end their strike, voting to accept a three-year contract that granted half their original wage demands.

The policy of the union bureaucracy was the biggest obstacle facing the miners at the time. The 1974 strikers were isolated and betrayed by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), then led by International president Harry Bridges.

The ILWU delayed giving the Local 30 strike funds for more than a month. More importantly, it refused to carry out a pledge to shut down the docks, and to prevent the movement of US Borax goods as well as Rio Tinto cargo.

In addition, throughout the strike, the AFL-CIO building trades instructed its members to cross the picket lines, and thus prevented the shutdown of the facility. These signals by the ILWU and the AFL-CIO that nothing would be done to mobilize the labor movement to stop union-busting encouraged the company to intensify its attacks on workers, their families and their town.

During August, in the middle of the strike, the US government was rocked by the resignation of President Richard Nixon—as a result of the exposure of the Watergate conspiracy. Gerald Ford then replaced Nixon. The ILWU refused to shut down the docks because it would have meant a confrontation with the government of Ford and the Democratic-controlled Congress.

The 1974 strike came during a period that had been marked by immense combativeness and political radicalization of the working class, both in the United States and internationally. But despite their militancy, these struggles were not armed with a political perspective independent from the major capitalist parties. That proved to be fatal.

In the US the alliance of the trade union bureaucracy with the Democratic Party blocked the development of a powerful political movement of the working class just as American capitalism was entering a period of protracted economic decline, which continues to this day. The upsurge of the working class movement in that period eventually arrived at a dead end, which provided the ruling class the opportunity to regroup and launch a counteroffensive in the 1980s and 1990s.

Reagan’s firing of 13,000 striking air traffic controllers and the smashing of their union, PATCO, was the signal for launching a violent campaign of union-busting, wage and benefit concessions and other rollbacks in the gains won by generations of struggle. The AFL-CIO and its affiliated unions isolated and betrayed strike after strike, enabling the ruling elite to amass vast personal fortunes as they slashed jobs and benefits, destroyed the industrial base of the country and carried on the most reckless forms of financial speculation.

The betrayals of the AFL-CIO were based on its nationalist perspective, undying defense of capitalism and hostility to socialism, and finally, its political subordination of the working class to the corporate-backed politicians in the Democratic Party.

Incapable of advancing any progressive response to globalization, the unions suppressed every struggle of the working class against downsizing and cost-cutting in the name of defending US corporations against international competition and “labor-management partnership.”

While the ILWU has periodically employed more radical sounding phrases, it has followed the same path. Since 1961, it has signed agreements that have led to the systematic destruction of jobs, the undermining of wages, benefits, working conditions and safety on the ports, including the six-year concession contracts in 2002 and 2008.

Like the rest of the unions the ILWU promoted Democrats as “friends of labor,” even as they collaborated with the Republicans in driving down the living standards of the working class. This culminated in the campaign for President Obama, who has proven to be nothing more than a ruthless tool of the financial elite.

Just like Rio Tinto, both the Democrats and Republicans are determined to make the working class pay the catastrophic decisions made by corporate executives, bankers and big business politicians. But workers did not cause this crisis and must not pay for it!

The most burning question is: on what basis must a fight be conducted?

First of all, it is necessary to see that this is a political struggle. All the forces of the state—from sheriff’s deputies guarding scabs right on up to the state and federal government—defend Rio Tinto and its investors against the workers.

The allies of the miners are not big business politicians like Nancy Pelosi, Arnold Schwarzenegger or Obama, but the working class throughout California, the US and the world.

Miners must take the conduct of this struggle into their own hands by forming rank-and-file committees, independent of the ILWU, which will directly appeal for working class support. This should include a call to public workers facing layoffs and wage cuts, auto workers at the threatened NUMMI plant in Fremont, and California university students fighting against tuition increases. A special appeal for common action must go out to Rio Tinto workers throughout the world, along with striking Vale Inco miners in Canada.

In order to defend its interests the working class must build its own mass political party to assert its own socialist solution to the crisis. This includes transforming the banks and major industries, including Rio Tinto, into publicly owned utilities, democratically controlled by the workers themselves.