I am Love, written and directed by Luca Guadagnino; The Leopard, directed by Luchino Visconti, based on the novel by Giuseppe di Lampedusa

Italian cinema in the post-World War II period was a colossal force. Any list of the most significant international film figures of that period would include the names of Roberto Rossellini, Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Vittorio De Sica and, of course, Luchino Visconti, along with numerous prominent screenwriters and many remarkable performers (Anna Magnani, Marcello Mastroianni, Giulietta Masina, Monica Vitti and others).

I am Love, directed by Luca Guadagnino

I am Love, directed by Luca GuadagninoItalian filmmaking’s decline has been precipitous. Claims are being made that Luca Guadagnino’s I am Love represents something of a revival, with numerous critics comparing the new film to Visconti’s 1963 masterpiece, The Leopard. In the end, although Guadagnino’s film has definite merits, this is a faulty and superficial assessment, with which this review will take issue.

I am Love centers on an Italian family whose great wealth is derived from a textile factory in Milan. The emotional suffocation inherent in an aristocratic milieu, where every whim is catered to by a bevy of white-gloved servants, is a central premise of the movie. The disintegration of the family’s hitherto orderly existence begins as the reins of the business are passing from Edoardo Recchi Sr. (Gabriele Ferzetti) to his son Tancredi (Pippo Delbono) and grandson Edo (Flavio Parenti). The question of succession in particular evokes the Visconti film. As well, a main character is named Tancredi. (There are also hints of Shakespeare’s King Lear.)

The Recchi family has been trapped by tradition for a long time. It is something of an open secret that the family collaborated before and during the Second World War with the Mussolini fascist regime. “The Recchis never lose,” says the disapproving elderly patriarch when Edo places second in a boat race.

Presiding over the Recchi household is Tancredi’s wife, Emma (Tilda Swinton). Despite her origins in the Russian middle class, she excels in the role. She has assumed, with the exception of a slight accent, the proper posture and attitudes of the Italian haute bourgeoisie. In this, she is mentored by her mother-in-law, the elegant Allegra (Marisa Berenson). Nothing seems so eternal as the family mealtime in the tapestry-adorned mansion.

It is a new world, however, and the Recchis’ place in it is changing. The Milanese business goes global, and Tancredi sells out to an Indian financier. The few scenes where this transfer of wealth and power to new social interests is rendered, particularly the business meeting in London, are the film’s strongest moments and strongest connection to the Visconti movie. The smooth-talking Sikh who represents the Indian firm explains smugly that “capitalism is democracy.”

Unfortunately, these scenes are not fully developed, tend to be treated as a subplot, and consequently form a small part of the overall dramatic tableau. Further, this event is largely held apart from the emotional turmoil on display in the film. In the end, the selling of the business and the psychological changes in the lives of the family are presented as two separate stories.

Recchi norms are being ruptured on all sides. Edo now plans to start a restaurant with his friend Antonio (Edoardo Gabbriellini). And when Emma discovers that her daughter Betta has left her boy friend and commenced a relationship with a woman, something is awakened in the mother and she begins a torrid affair with Antonio. The young man’s culinary flair is sexually arousing as is his tiny shack in the middle of raw nature.

Yet the 180-degree transformation in Emma’s lifestyle makes little apparent dent in her appearance or demeanor. And it’s never really made clear why Emma rebels in the first place. Tancredi is not an ogre. Her pent-up frustrations apparently reach a boiling point. Frankly, this is small stuff, a repressed upper-class woman who finds there’s more to life. We haven’t progressed much since Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, first performed in 1879, if at all.

Cropping one’s hair also appears to be a sign of rebellion for both mother and daughter. In other words, a few outward adjustments substitute for the dramatic working through of a significant internal revolution.

While Edo fears for the post-industrial fate of the Recchis, he has been Betta’s confidant in regard to her new sexual orientation. Moreover, there is a hint he is secretly in love with Antonio. When he connects the fairly obvious dots that point to the Emma-Antonia affair, there is a tragic denouement. The family’s foundations begin to crumble.

The basis for comparisons between I am Love and Visconti’s The Leopard lies in director Luca Guadagnino’s admirable attempt to chronicle the changing fortunes of a dynasty in a sumptuous and socially detailed manner. The film has a serious and intelligent look to it. But for cinematic language to be truly rich, it must have a correspondingly rich content. Unfortunately, I am Love winds up, in a careless and almost startlingly disappointing fashion, reducing great social tensions to sexual discontents and preferences. In the process, it somewhat ludicrously gives the seductive qualities of food and sex a transformative role.

Something important is referenced in the film about the global economy and the alterations within the ruling class. But only referenced, only touched upon. Unhappily, I am Love is in another indication that today’s filmmakers still have a tendency to gloss over the decisive social facts of life and subordinate them to timeless—and often tiresome—personal dramas.

Guadagnino never integrates his social and psychic analyses. Or, to put it more bluntly, he runs the danger of suggesting that the bourgeois characters’ coldness and rigidity determines the social relations and events, rather than the other way around. And what if Tancredi were warmer? What if the family members could express a healthier pansexuality? Would this alter Italian life and society?

With Visconti, matters are different. He is someone for whom the meticulous exploration of the relationship between human beings and the social process is a major component of his art.

The Leopard

The Leopard

The LeopardVisconti (1906-1976) was instrumental in creating the modern cinema with his early neo-realist works, Ossessione (1942), and La Terra Trema (1948), the latter considered a cornerstone of the movement. He then gravitated to more highly structured historical and psychological works, such as Senso (1954) (see http://www.wsws.org/articles/2010/jun2010/sff6-j03.shtml), The Leopard (Il Gattopardo, 1963) and Death in Venice (Morte a Venezia, 1971).

Luchino Visconti

Luchino ViscontiHis films were enriched by his career in opera and theater, as well as a deep knowledge of literature and painting. Hailing from a wealthy, aristocratic family, one of the most distinguished in the country, the artist rejected his origins and joined the Communist Party. Of course, his life and art could not have been unaffected by the fact that the Stalinist party became the major prop of post-war Italian capitalism.

Based on Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel, Visconti’s The Leopard recounts the decline of the Sicilian aristocracy in 1860-1862 during the period of the Risorgimento. “The Resurgence” was the movement for Italian unification that culminated in the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

For its American release, the film’s US distributor, 20th Century Fox, shortened The Leopard’s running time from 185 minutes to 161, and included a dubbed English-language soundtrack. In 1983, Fox rereleased the film with its far superior original Italian soundtrack and at its original length. In 2004, after a major overhaul of the original camera negative, Criterion issued a DVD edition and now a Blu-ray upgrade of its 2004 transfer. The current copy is beautiful.

The Leopard is the tale of Don Fabrizio Corbera, the charismatic Prince of Salina (Burt Lancaster), who witnesses with philosophical resignation the passing of the feudal era as the Italian peninsula is united for the first time since the fall of the Roman Empire.

In its opening shot, the camera pans the prince’s grand estate. Inside the palace, his family is in morning prayer. But the rebel Garibaldi disrupts the ritual. His Red Shirts are in the process of defeating the Bourbon troops and occupying the Sicilian capital of Palermo in the name of Victor Emmanuel, the first king of a united Italy.

Fabrizio sees the writing on the wall. The poor string up the town’s Bourbon mayor. The prince says to Father Pirrone (Romolo Valli), the family cleric: “[The] Holy Church has been granted an explicit promise of immortality; we, as a social class have not. Any palliative which may give us another hundred years of life is like an eternity to us.” The priest fears for the fate of the Church, and the possibility of the seizure of some of its vast lands by the new regime, pointing to its role in placating the poor.

The prince soon learns that his beloved nephew Tancredi (Alain Delon) is fighting with Garibaldi’s forces. If the nobility refuses to accept the Kingdom of Italy, insists the young man, “They will foist a republic on us.” He goes on, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change.” This is a central concern of the film, highlighting the aborted, ultimately anti-popular nature of Italian unification, with all sorts of implications for subsequent Italian history. Visconti leaned heavily on the writings of Antonio Gramsci on this score.

The prince realizes the truth and practicality of Tancredi’s words. This is a remarkable scene in which Visconti uses mirrors to highlight a historic (and generational) transformation. When Tancredi enters the room, his face fills the mirror Fabrizio is using to shave, as if he is pushing his uncle out of the way. Later, the prince stands before a full-length mirror. His presence is commanding. But close by, Tancredi’s face is shown as a dark profile in a third mirror, hints of the Angel of Death.

In fact, life’s succulence seems absent in the arid terrain through which the prince and his entourage journey to their summer villa in Donnafugata. On arrival, they are greeted by a new social elite represented by the mayor, Don Calógero Sedàra (Paolo Stoppa), a wealthy businessman and landowner. A former Garibaldini, he is a member of the rising bourgeoisie that preys on the distressed aristocracy and now capitalizes on the chaos sown by Garibaldi’s forces. While the prince exudes gravitas, Calógero is a shifty social climber.

Inside the church, the nobles sit in their allocated pews. There is a riveting shot panning the faces of the members of the family. Worn-out and dusty, they are arrayed like marble or stone figures in a family mausoleum.

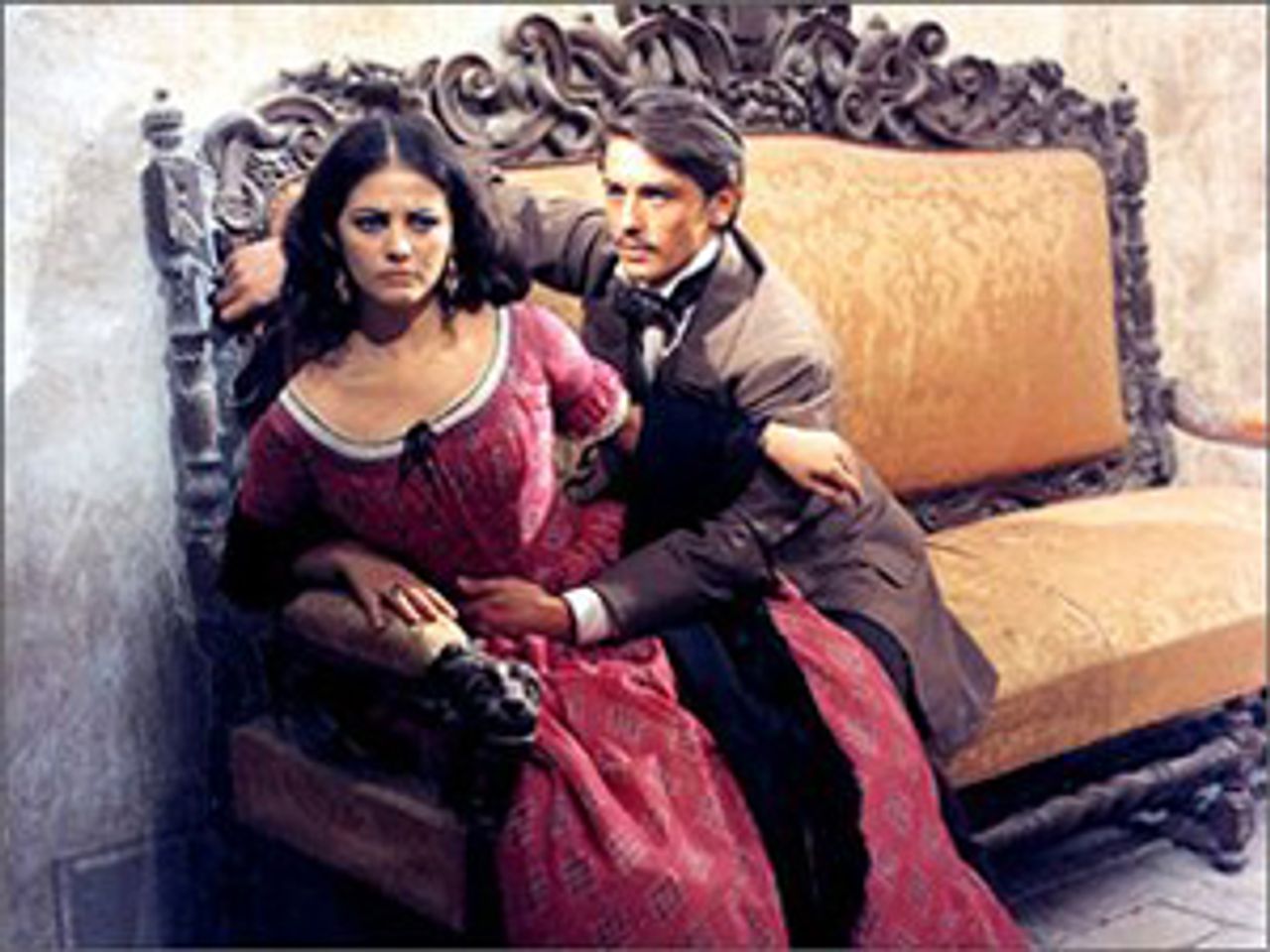

Don Calógero’s beautiful daughter Angelica (Claudia Cardinale) sweeps Tancredi off his feet. The union of a member of a nouveau riche with a penniless noble is fortuitous, as the prince recognizes. This, despite the crudeness of the arrivistes—for example, when Angelica emits a bawdy, drawn-out laugh at dinner, echoing down the palace’s hallowed corridors.

In the town hall, Fabrizio toasts the rigged plebiscite in favor of a united Italy under a portrait of Garibaldi. In this sequence, the new Italy’s tricolors are featured in the drinks and candles. Fireworks light the sky; in the foreground, the prince gazes pensively into the void.

When Tancredi and Angelica, now engaged, explore the deserted parts of the palace, in another unforgettable scene, mirrors again come into play. This time to reflect decomposition: objects that have been discarded and mothballed. (“[L]ittle powdered demons had been put to flight…as sleeping embryos, hibernating under piles of dust,” Lampedusa writes in his novel.) The vast, labyrinthine dimensions of the palace, the countless empty rooms (many of which have not been used for centuries), the enormous canvases scattered about, the layer of dust and neglect…everything speaks to a ruling class that is wasteful, careless, obsolete, if cultured and gracious.

Shifting with the tides, Tancredi now supports King Emmanuel’s army, which will eventually rout Garibaldi as he marches on Rome in an attempt to force the Papal States into the Kingdom. This ends the revolutionary phase of the Risorgimento. Tancredi, the charming and wily opportunist, is parlaying the (declining) fortunes of his family into political power. Law and order is just what is needed for Sicily, he says, as some of Garibaldi’s men are executed off-screen.

Approached to serve in the new government, Fabrizio responds: “But I cannot accept, I am a member of the old ruling class. Inevitably compromised with the Bourbon regime, and tied to it by chains of decency if not affection. I belong to an unfortunate generation, swung between the old world and the new, and I find myself ill at ease in both. And what is more, as you must realize by now, I am without illusions; what would the Senate do with me, an inexperienced legislator who lacks the faculty of self-deception, essential requisite to guide others.”

The ballroom scene from The Leopard

The ballroom scene from The Leopard The film is bracketed by two operatically staged events: the battle scenes in Palermo, ending in Garibaldi’s victory, and the grand ball towards the film’s end. Both are presented in blazing, artificial colors. The first, the explosive birth of a society; the second, a dimming universe. Lancaster is particularly affecting at delivering the feel of one being drained of vital fluids. The decadence and decline of the feudal class is emphasized throughout the ball’s long sequence. Looking upon a group of young women acting foolishly, Fabrizio remarks that “frequent marriages between cousins does not improve the stock.”

The prince is something of a renaissance man. His last moments on screen speak to his interest in astronomy as he finds solace in the apparently static order of the firmament: “Oh faithful star, when will you give me an appointment less ephemeral, far away from all this, in your own region of perennial certitude?” Along with a new order come sciences that already reveal there is as little certitude in the heavens as there is on earth.

It should be noted The Leopard has its light touch: Fabrizio speaks of his religious wife and his need to cavort with prostitutes: “I’ve had with her, seven [children]; and never once have I seen her navel.” To Father Pirrone’s embarrassment at seeing the prince lift himself out of a tub, the latter says: “You’re used to naked souls, naked bodies are far more innocent.” The priest is one of the film’s semi-comic characters, and not portrayed simplistically.

Visconti’s epic is a work of astonishing proportions. The breadth and depth of his treatment of the subject matter is on a scale almost unimaginable in recent cinema. History lives through every pore of the film. Visconti ambitiously tries to present a historical panorama, complete with its political and cultural transformations, bringing to life real people, not fleshed-out social types. As the bridge between the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, Tancredi’s political makeover is especially nuanced.

It is difficult to fully grasp the film’s complexity, its array of landscapes and figures responding to a transitional epoch. The ambitiousness, at times, makes the work a bit stiff and unwieldy. It is trying to do so much. But one must acknowledge Visconti’s determination to address in a profound way the interplay between the political and the personal and the rarity of the endeavor.

One feels at times that Visconti, like Lampedusa, lacks the necessary critical distance from this leading figure and even, at times, shares his sense of historical and personal resignation. With Visconti, this is less excusable. The film largely dwells inside the prince, bathing in his fascinating qualities and observations. We see him, but there are other things we need to see as well.

The Leopard’s shared intimacy with Fabrizio at times bleeds into its social outlook, and one cannot help but feel that Visconti’s own disappointment with developments in post-war Italy—the restoration of capitalism, the inability of the working class to take power—comes into play here. The population is largely passive, underscored in the scenes in which Fabrizio’s servant and hunting guide Don Ciccio sings the praises of his noble masters and the old order. This is only one figure, and no doubt based on a real social layer in Sicily, but as virtually the only “popular” figure singled out, the choice is somehow revealing.

Claudia Cardinale and Alain Delon in The Leopard

Claudia Cardinale and Alain Delon in The LeopardWith the exception of the sequence in which the poor side with Garibaldi in Palermo, the peasants are shown quietly tilling the land in the midst of continual tension. Some of this is included in Visconti’s choice of subject matter—a book that deals with a very stagnant locale and social mentality, described by Fabrizio as “a terrifying insularity of mind.”

Again, the film’s refrain is “to stay as they are, things will have to change.” Fabrizio notes that his aristocratic class will be replaced by “jackals,” and there is an element of truth in that. He continues, “And the whole lot of us, leopards, jackals and sheep”—the nobility, the bourgeoisie and the population—”we’ll go on thinking ourselves the salt of the earth.” Lampedusa, the novelist, who came from this aristocratic background, would naturally have his own view of things, but Visconti seems uncomfortably close at times to suggesting that we should share it too.

In any event, this is an enormous film, in an excellent format. One can only recommend it highly.