This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

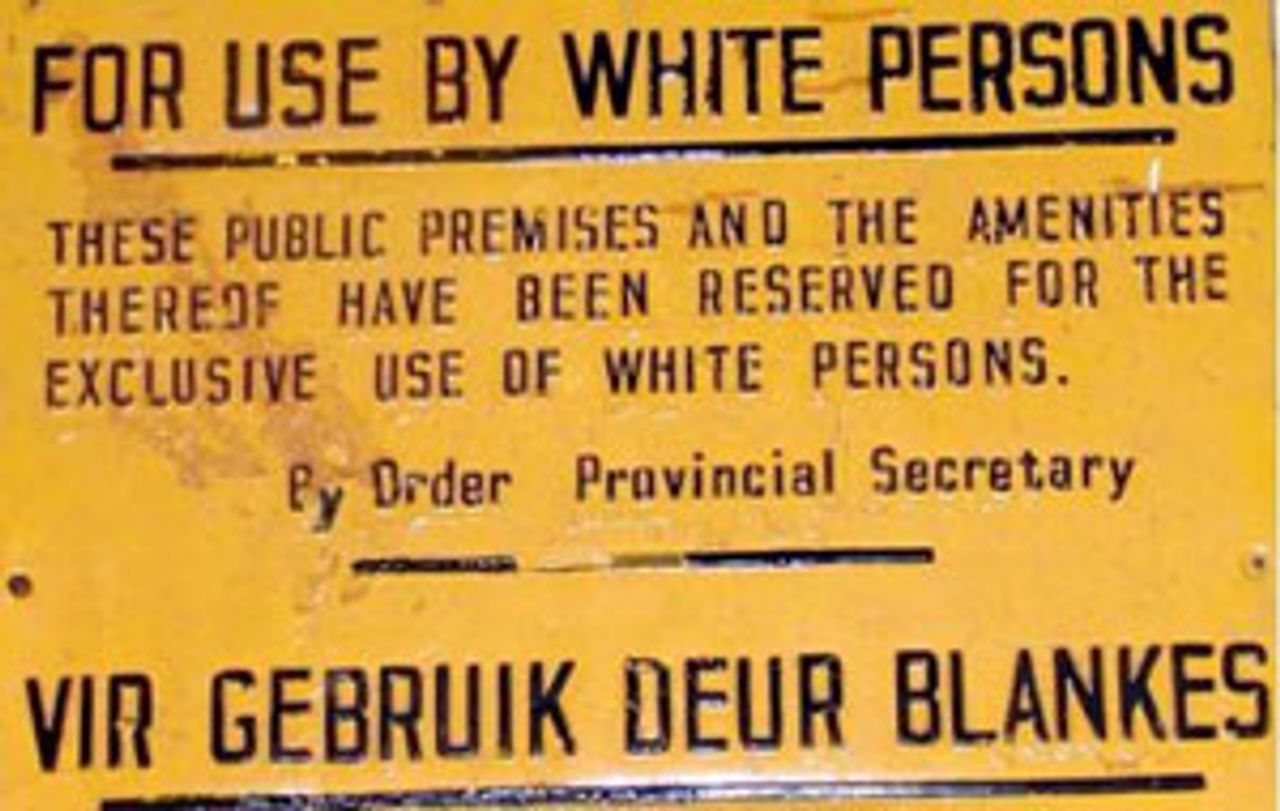

25 years ago: Bloody week in South Africa

South African Apartheid

South African ApartheidThis week in 1986 in South Africa dozens of black Africans demonstrating against the racist Apartheid regime were killed at the hands of white security forces.

In the village of Atteridgeville, near Pretoria, police used whips and tear gas to break up a demonstration of 2,000 women. In Port Elizabeth, two demonstrators were shot and killed by police. In Graaff Reinat, a demonstration marching toward a white neighborhood was attacked by police, resulting in the death of a woman.

In Alexandra, near Johannesburg, a funeral for victims of state violence drew a crowd of 6,000 that turned into a demonstration. Police set on it, killing five, among them a woman and 13-year old boy. Officially 19 died in the violence in Alexandra, but another estimate put the figure at 80. Foreign media were restricted by the South African regime from documenting the violence.

The violence in Alexandra was so intense that Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu was brought into appeal to blacks to cease their demonstrations. “There is a growing sense of impotence, but they did listen.” Tutu said afterwards. “It is tense, very, very tense. It could go one way or another.”

Since January 1, 1986, more than 100 had died in the violence, and since the uprising began in September, 1984, more than 1,100 had been killed.

50 years ago: Global outrage over Lumumba killing

Patrice Lumumba

Patrice LumumbaAfter the ruler of Congo’s secessionist Katanga province declared that Patrice Lumumba had been killed by villagers after attempting to escape from prison, angry protests erupted all over the world against Belgium, the US, and the United Nations and its secretary-general Dag Hammarskjold. Lumumba had in fact been murdered with the backing of the US and Belgium. The Yugoslav state press agency, Tanjug, had correctly reported that week that the nationalist and democratically-elected leader of the Congo and two associates had been shot one-by-one by a Belgian army captain.

Protests took place this week in 1961 outside of the Belgian embassies in Cairo, Egypt (then the United Arab Republic), in Moscow, Warsaw, Belgrade, London, Paris, Washington D.C., Bombay, Jakarta, and in Accra, Ghana. In each of these cities Belgian embassies were attacked, and in some cases US, British, and French embassies were threatened. In China, a crowd estimated at over 500,000 rallied to condemn the killing. Other protests took place in Rome, Vienna, Tokyo, Melbourne, and in Morocco, Pakistan, and Senegal. In Paris, 106 were arrested outside of the Belgian embassy. Seventy-two African students studying in Israel sang songs and marched through the streets of Israel carrying placards in English, French and Hebrew, one of which read “U.N. How?”

In Washington D.C., about 25 students from all-black Howard College pelted the Belgian embassy with eggs. On February 15, 60 African-Americans invaded the UN Security Council chamber while in session.Two dozen were injured in the melee.

On orders of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, all flags in Ceylon were flown at half mast. Cuban president Fidel Castro blamed the killings on Western imperialism, and the Indonesian government condemned them as murder. In Tunisia, the Government of Habib Bourguiba telegrammed Hammarskjold to express its “profound indignation” and threatened to remove its troops from the UN force in the Congo. Morocco said the killings were “premeditated murder” for which the UN was guilty due to its “silence and complicity.” Ghana President Kwame Nkrumah charged the UN with “open connivance” in Lumumba’s downfall. Pakistan also charged murder.

75 years ago: Popular Front wins Spanish general election

Francisco Franco

Francisco FrancoEstablished only in January, the Spanish Popular Front won the national general election on the 16th of February with just over 34 percent of the vote, narrowly defeating the right wing National Front. The Popular Front comprised the Communist Party, Socialist Party, the POUM and a number of liberal bourgeois parties.

As in France and elsewhere, the express purpose of Stalin’s Popular Front policy in Spain was to tie the working class to the liberal capitalist political forces and block revolutionary struggles. This counterrevolutionary policy flowed from Stalin’s conception of “socialism in one country”: by sacrificing the Spanish working class, Stalin hoped to entice the British, French, and American governments into an anti-Nazi alliance.

Nowhere was the bankruptcy of this outlook expressed with such acuteness as in Spain. Like Russia before the revolutions of 1917, the “liberal” Spanish bourgeoisie was weak and subordinate to foreign capital; its interest in democracy was only a means by which it sought an accommodation with the reactionary elements that dominated the state: the latifundia, the church, the royal court, and the army officers.

The Spanish working class, on the other hand, wielded enormous power by virtue of its control over factories, mines, ports, and its demographic domination of the major cities Madrid and Barcelona. This it had announced by a growing crescendo of strikes and riots in the early 1930s, including worker insurrections in Asturias and Barcelona in 1934. In Asturias coal miners occupying the capital of Oviedo were savagely crushed by General Francisco Franco, who destroyed much of the city in the process.

100 years ago: Madero returns to Mexico

Francisco Madero

Francisco Madero On February 14, 1911, Francisco Madero, at that point the acknowledged leader of the Mexican Revolution, crossed the US border from Texas to assume leadership of the insurrection against the dictatorship of President Porfirio Diaz.

Several days later Madero gave an interview to an American journalist in the major rebel encampment 20-some miles south of Guadalupe, Chihuahua, laying out his plans for victory. Madero said that the rebel fighters were superior to the federales, because they volunteered and “are fighting for ideals and for liberty and for their rights.” Additionally, Madero said that his army had the support of “the people, all the people,” who told his officers the movements of the government soldiers.

In describing the aims of the revolution, Madero stressed democratic issues. The rebels were fighting for “the Constitution, for poll rights, and for general education,” he said, adding that he would favor greater local political autonomy.

Meanwhile, rebels were gaining strength beyond the states that border the US. In Durango rebels gained territory, and in Puebla in the south they attacked railroads, telegraph lines, and initiated hostilities with federal forces in a number of towns and villages.