This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Rightward shift on US Supreme Court

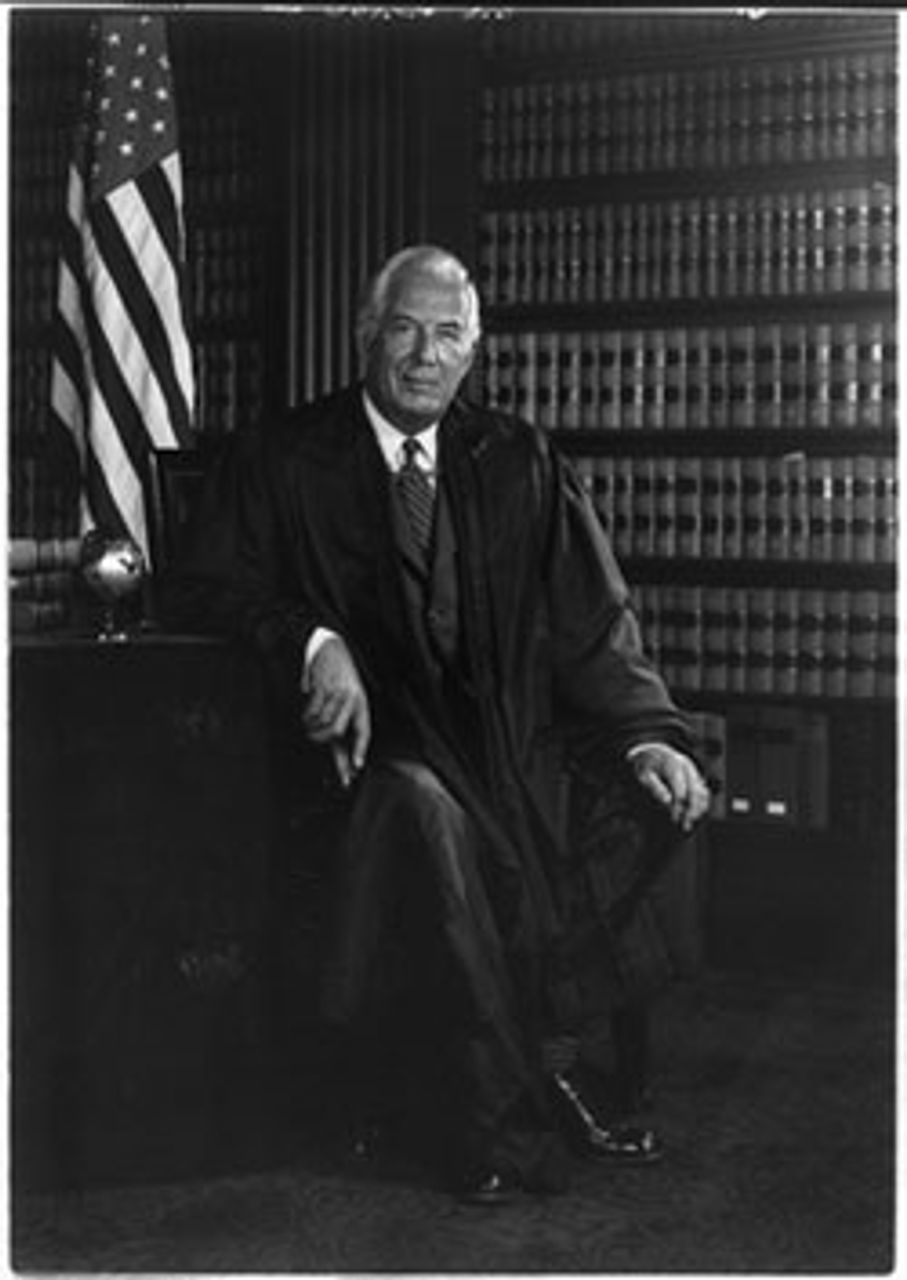

Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger

Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren BurgerOn June 17, 1986, the press reported that Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger would retire and President Ronald Reagan would nominate the court’s most right-wing member, Associate Justice William Rehnquist, to replace him. It was also reported that Reagan would nominate one of the nation’s most right-wing judges, Antonin Scalia of the Federal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, to assume the vacant high court seat left by Burger’s retirement.

Up to this point, the sharp shift to the right by the American ruling class that was signaled first by Jimmy Carter’s victory in the Democratic presidential primary contest of 1976 and then by Reagan’s election victory in 1980 had not yet registered on the high court, which generally continued to hand down rulings in line with those of the liberal Earl Warren Court of 1953 to 1969. This was mainly because appointments to the Supreme Court carry lifetime tenure.

Burger “will be leaving a Supreme Court that in terms of judicial doctrine has not been notably different from the one he inherited 17 years ago when President Nixon named him the 15th chief justice” of the court, the New York Times noted. “The court under Burger proved to be every bit as ‘activist’ as the [Warren] Court that Richard M. Nixon campaigned against.”

In a book entitled The Burger Court: The Counterrevolution that Wasn’t (1983), Professor Vincent Blasi of Columbia Law School wrote that the Burger court was guided “almost exclusively by discrete, pragmatic judgments regarding how a moderate, sensible judicial accommodation might help to resolve a potentially divisive public controversy.”

No more. Rehnquist was an outspoken judicial opponent of desegregation, reproductive rights and federal guarantees on voting rights. According to one account, as a rule Rehnquist voted “with the prosecution in criminal cases, with business in antitrust cases, with employers in labor cases, and with the government in speech cases.” Scalia was, if anything, even further to the right.

While there was some criticism of Reagan’s choices, elected Democrats signaled they would not seek to block Rehnquist’s elevation or Scalia’s selection.

50 years ago: Britain creates “independent” Kuwait

On June 19, 1961, the United Kingdom agreed to terminate its colonial protectorate over the oil-rich Sheikdom of Kuwait, a tiny Middle Eastern country at the head of the Persian Gulf. The agreement handed power over foreign policy, and total power within Kuwait, to Sheik Abdullah III Al-Salim Al-Sabah of the Al-Sabah dynasty.

On June 19, 1961, the United Kingdom agreed to terminate its colonial protectorate over the oil-rich Sheikdom of Kuwait, a tiny Middle Eastern country at the head of the Persian Gulf. The agreement handed power over foreign policy, and total power within Kuwait, to Sheik Abdullah III Al-Salim Al-Sabah of the Al-Sabah dynasty.

The deal was a calculated blow against the national aspirations of Iraq. As early as 1899, in the failed Anglo-Ottoman Convention, Britain had attempted to wrest Kuwait from the heavily populated Tigris and Euphrates river valleys, to whose major cities, including Baghdad and Basra, Kuwait had been administratively and historically linked under the Ottoman Empire. After World War I, when Iraq was made a British protectorate, the quisling government in Baghdad agreed to the British-mapped border.

The creation of Kuwait on June 19 denied Iraq access to deep water ports, took the sheikdom’s enormous oil wealth (discovered in 1938) away from the more heavily populated regions upriver, and further hemmed in Iraq, which was surrounded by US and British allies Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Jordan and Israel.

In response to Britain’s move, on June 27, the nationalist Iraqi government of Abd al-Karim Qasim mobilized for an invasion of Kuwait. Kuwaiti Amir Al-Sabah quickly appealed to the UK for support, and London sent soldiers, aircraft and naval vessels. The Iraqi invasion was blocked, and within three years the Baath Party of Saddam Hussein led a coup that resulted in the killing of Qasim and the massacre of thousands of Iraqi socialists and trade unionists.

Alongside Egypt, Iraq was the Arab nation where socialism and pan-Arab nationalism had taken deepest root. Qasim, a military officer like Egypt’s Nasser, had in his three years in power removed Iraq from a grouping of pro-US Middle Eastern states called the Baghdad Pact and from the British-dominated Sterling bloc. He had also helped to form the OPEC oil cartel, restricted the power of foreign oil conglomerates, and established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. At the same time, to reassure the Iraqi elite and the Western powers, Qasim took measures against the Iraqi Communist Party, which nonetheless continued to support his bourgeois government.

75 years ago: Gorky dead at 68

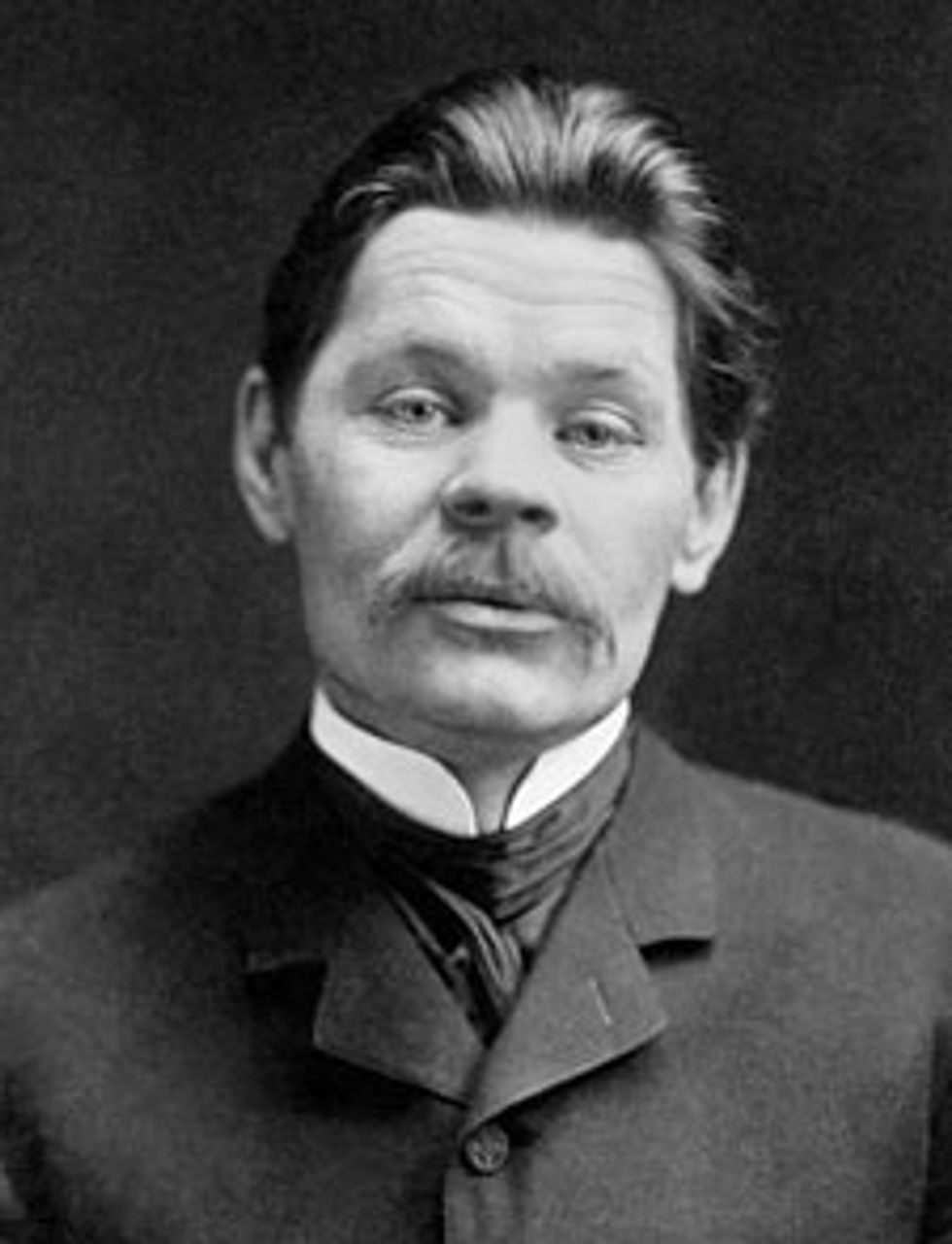

Maxim Gorky in 1906

Maxim Gorky in 1906 On June 18, 1936, Russian writer, playwright, critic, editor and socialist Maksim Gorky (Aleksei Maksimych Peshkov) died at the age of 68. Writing in the tradition of Tolstoy, though with Russian proletarian protagonists rather than figures drawn from the peasantry, Gorky railed against the daily injustices meted out by tsarist society and argued for equality and radical change.

Orphaned at the age of nine, the young Gorky worked his way across Russia. Like Mark Twain and Charles Dickens, he would in his later literary work draw upon his formative experiences in the urban and rural labor force. Coming to prominence in the penultimate year of the 19th century with the publication of his first book Essays and Stories, Gorky was in his early writings an inspiration to socialists, among them Leon Trotsky, whom Gorky came to know in London.

The writer subsequently became a sympathizer, collaborator and “fellow traveler” of the Bolsheviks. Despite being on friendly terms with both Lenin and Trotsky, Gorky had a somewhat uneven relationship with the party and, despite his legacy, his later work, influenced by “god building,” tilted towards idealistic and ecclesiastic conceptions. He left the Soviet Union in 1921 to live on the island of Capri off Naples, Italy.

After returning from convalescence to the Soviet Union in 1931, Gorky was pressured into providing support for the Stalinization of Soviet literature. Subsequently blamed for the Stalinist monstrosity of “socialist realism,” Gorky’s work is much more penetrating and moving than that movement’s Stakhanovite posturing. After Gorky’s death, unproven rumors circulated that he was poisoned on Stalin’s orders.

Later that year, Marxist cultural critic Aleksandr K. Voronsky wrote on Gorky’s passing. “Did Gorky fear death?” Voronsky asked. “He didn’t whine before it, or complain, or find refuge from it in far fetched ideas or illusions. He greeted death boldly, calmly, looking it straight in the eye, as was befitting the best proletarian artist. Despite his years, he still had an unusually strong thirst for life, and he particularly wanted to live in the land of socialism, to take the most active and intimate part in building a new society. He thought about life, not about death. He loved art with a jealous love. He was a man of great thoughts, great faith and a great heart. Schopenhauer once made the remarkable comment that a genius is a man to the highest degree. Aleksei Maksimych Gorky-Peshkov was just that: a man to the highest degree.”

100 years ago: International strike of seamen

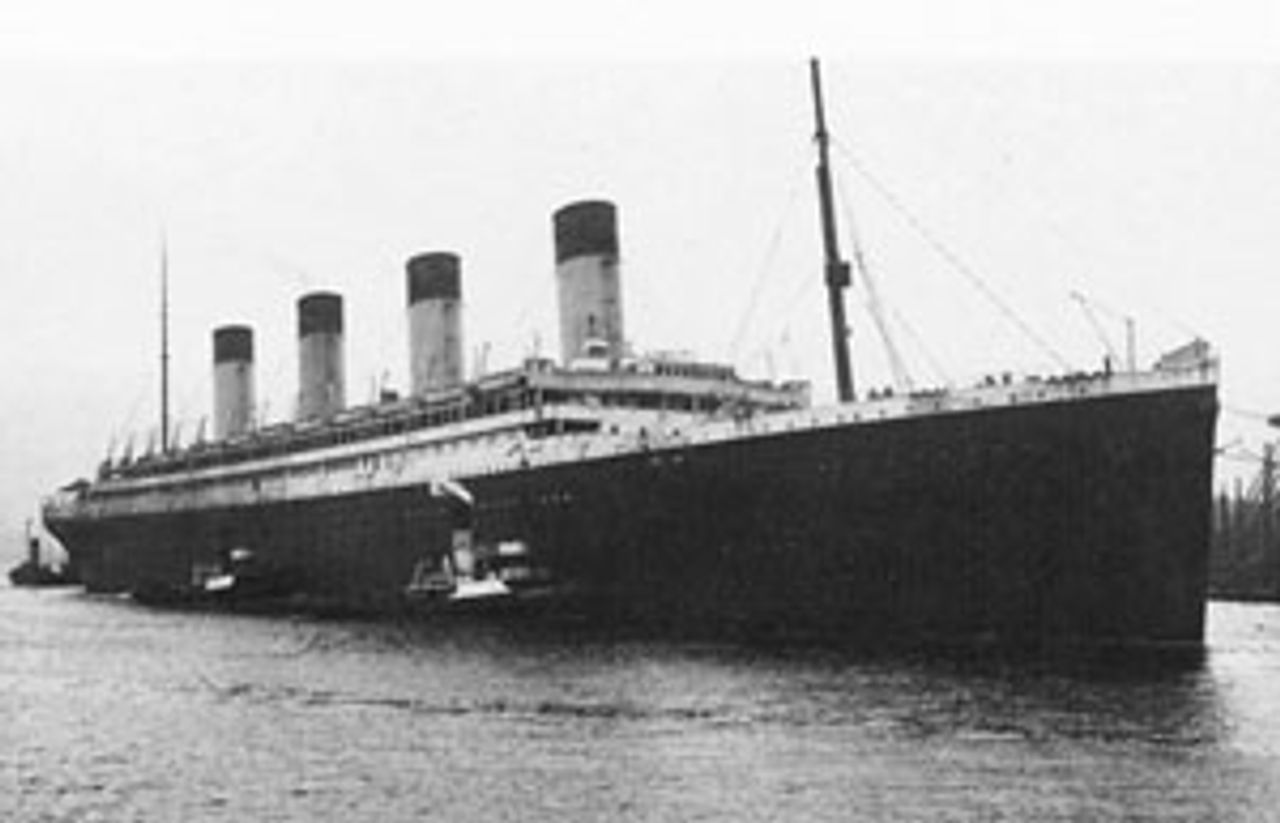

RMS Olympic in 1911

RMS Olympic in 1911On June 13, 1911, a semi-coordinated strike by several seamen’s unions shut down shipping lines in a number of countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Belgium.

The struggle was initiated by coal porters, firemen and sailors in the UK’s National Union of Seamen (NUS) who were demanding higher wages and better conditions. Many major lines were affected, and the ports of London, Glasgow, Liverpool and Bristol were hamstrung.

The signal for the strike was given on the night of the 13th at a mass meeting of 3,000 sailors and firemen in East London, where a banner was unfurled reading: “War is Declared.” The strike quickly spread to Antwerp and within a few days the Atlantic Coast Seamen’s Union in the US had shut down a number of major liners operating out of New York.

Through the following week the struggle gained strength, with longshoremen in England and Scotland joining in and the demand for a general strike percolating in the ports of the US East Coast. In the US, a ship called the Momus turned fire hoses on a tug that was attempting to evacuate striking seamen who were being forced to sea by the operator, Morgan Lines. Later, at the Morgan Lines pier on West Street in New York, a street battle took place pitting hundreds of strikers and their supporters against strikebreakers and police.

The strike illustrated the increasingly global character of the economy, and, in particular, certain trades such as those associated with the shipping industry. Yet it also exhibited the limited conceptions of the trade union movement.

Even as it attempted to appeal to workers in other countries, for example, the NUS raised as one of its critical demands that the struck lines cease hiring “Asiatic labor.” Serious international coordination was lacking.

Liner operators began to cut deals with different sections of the workforce, country by country, first in the US. There the threat of a general strike brought significant concessions on wages and conditions. In the UK, where the strike dragged on longer, lines made separate deals with workers in different ports.