PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE | PART FOUR | PART FIVE

Between 1968 and 1975 a series of economic and political crises convulsed world capitalism. Advanced capitalist countries were shaken by massive strike waves, which in France in 1968 reached revolutionary proportions. In 1974, a coal miners’ strike drove the Tory Heath government in the United Kingdom from power. Right-wing dictatorships fell in Portugal and Greece.

The crisis of American capitalism lay at the center of the world crisis. In 1975, the US imperialist war in Southeast Asia came to a humiliating defeat with the fall of Saigon. A year earlier, President Richard Nixon was forced to resign from office as a result of the Watergate scandal, which was bound up with the debacle in Vietnam.

The enormous financial cost of the Vietnam War had accelerated the decline of US capitalism and the drain on American gold reserves. It was in response to this crisis that Nixon, in 1971, unilaterally removed the gold backing from the US dollar. This failed to resolve the decline of US capitalism relative to its chief European and Asian rivals, and it helped to set into motion the high inflation that characterized the 1970s.

Like a number of other countries, the US experienced heightened strike activity in the 1970s, in particular during the first years of the decade. Strikes raged across the US, attested to by the Bulletin, the newspaper of the Workers League, the predecessor of the Socialist Equality Party. Bulletin reporters covered hundreds of these struggles. The Workers League fought tenaciously to mobilize the rank-and-file workers against the trade union bureaucracy and its policies of class collaboration and support for the big business Democratic Party.

The prominent role the Workers League played contrasted sharply to the indifference of radical protest groups, which branded American workers as pro-imperialist and racist and referred to the unions as “white men’s job trusts.” The milieu of middle-class radicals had been moving to the right since the waning of the anti-Vietnam War protest movement in the early 1970s.

The Bulletin, newspaper of the Workers

The Bulletin, newspaper of the WorkersLeague

Inflation played a major role in fueling the strikes of the 1970s, as workers endeavored to maintain the buying power of their wages in the face of rising prices. To a certain degree, workers succeeded in keeping wages in line with inflation. At times they won wage hikes greater than the inflation rate, as when steel workers secured a three-year, 30 percent raise in 1971. Although the AFL-CIO bureaucracy succeeded in blocking these struggles from coalescing into a political challenge to the two-party system, from the standpoint of US capitalism, the situation was intolerable.

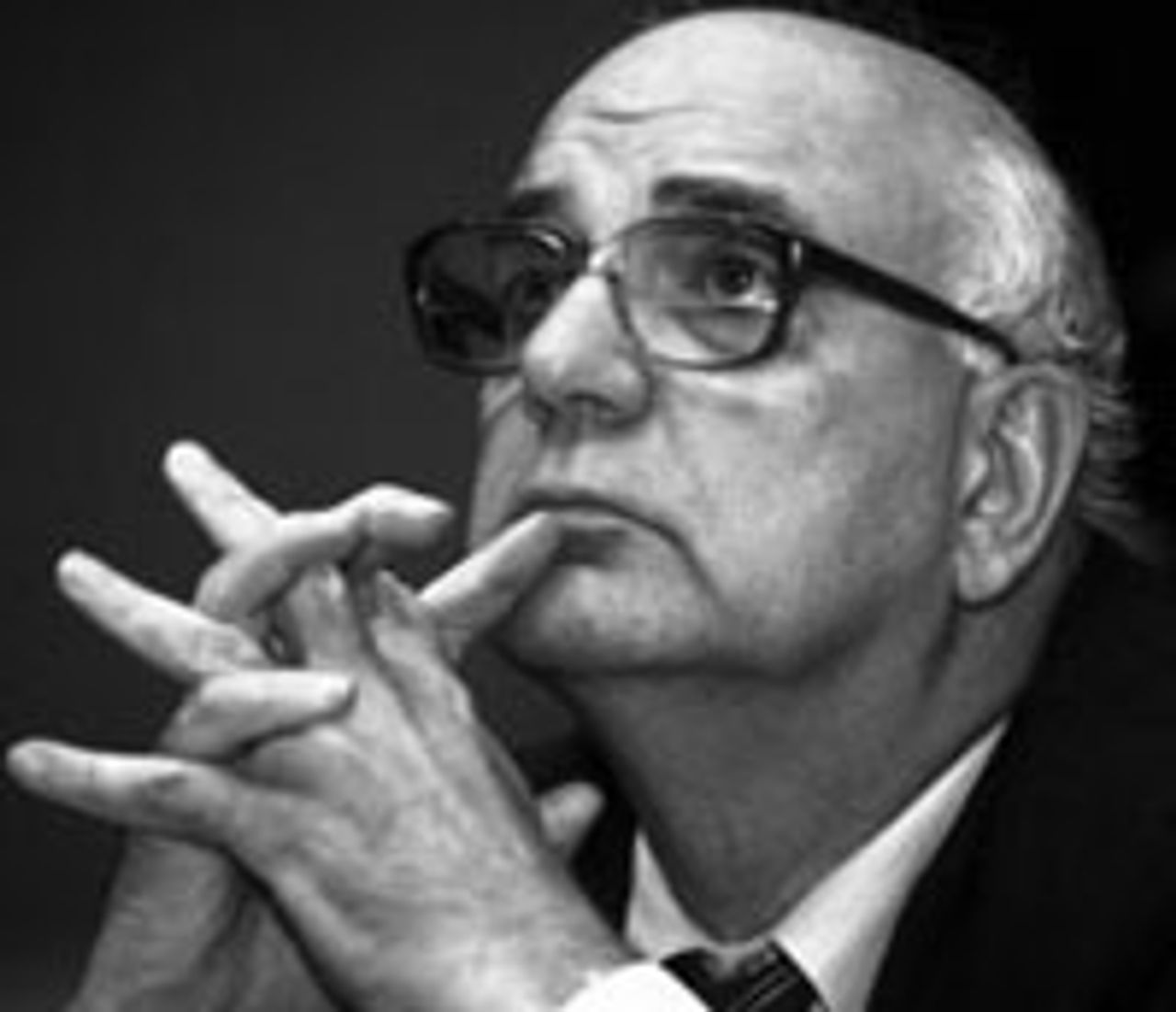

Paul Volcker, a Chase Manhattan bank executive appointed by Democratic President Jimmy Carter to head the Federal Reserve Board in 1979, put forward the ruling class position succinctly when he declared that year: “The standard of living of the average American worker has to decline.”

Volcker’s interest rate “shock therapy,” raising the benchmark federal funds lending rate to over 20 percent, aimed to resolve inflation and undermine the combativeness of the working class by creating mass unemployment. The Fed, acting in behalf of the Carter administration and the American ruling class, deliberately set out to force the closure of large sections of US manufacturing that were no longer profitable. Over 6.8 million jobs were lost to plant closures between 1978 and 1982. Whole cities and regions—primarily those associated with mass production industries and industrial unions—were devastated, including much of the industrial Midwest.

Paul Volcker

Paul VolckerHowever, it was not enough simply to alter economic conditions to the detriment of workers, as experience had taught. Nixon’s attempt to impose wage controls in 1971 had failed to stem the strikes of the 1970s. The ruling elite sought a clear and decisive defeat of the labor movement. The goal was to intimidate and weaken the working class and encourage private industry to launch a union-busting campaign.

The battle had to be chosen carefully. In the 111-day coal miners’ strike of 1977-1978, Carter attempted to impose a Taft-Hartley back-to-work order on the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). The miners flouted the order, burning copies of Carter’s edict on the picket lines. Carter was humiliated and lost the confidence of the ruling class.

Striking miners in 1978, holding copies of the Bulletin

Striking miners in 1978, holding copies of the BulletinA different target was needed. Indeed, when the UMWA once again initiated a national strike in May of 1981, just three months before the PATCO struggle, the new Reagan administration did not invoke Taft-Hartley or otherwise directly intervene. This is because preparations were already far advanced to make an example of PATCO, a small and relatively isolated union.

In early 1980, the Carter administration began to make elaborate plans for dealing with the air traffic controllers. PATCO was aware that Carter was singling them out and for this reason endorsed Reagan for the presidency in 1980 after the latter assured the union that he would respond to their grievances.

The AFL-CIO, the United Auto Workers and other unions had already made clear that they would not mount a serious struggle against union-busting or wage-cutting. The Chrysler bailout of 1979 was a landmark.

The United Auto Workers (UAW), one of the most powerful unions in the US, signed off on wage and benefit concessions in order to secure a government loan to keep Chrysler from going bankrupt. The UAW told workers that this was a one-time give-back to the company, made necessary by extraordinary circumstances, and that the workers’ sacrifice would return the company to profitability, after which the lost pay would be returned. As the Workers League warned at the time, the betrayal carried out by the UAW at Chrysler was the beginning of a policy of concessions that has continued and escalated ever since.

The Bulletin warned in 1979: “There is one essential question that arises out of the Chrysler bankruptcy: Who is to pay for the breakdown of the capitalist profit system, the working class or big business? The answer of big business, the banks, the Democrats, the Carter administration and the UAW bureaucracy is, of course, the working class.”

The Carter administration’s role in pushing through the Chrysler bailout on the backs of auto workers laid bare the fact that the Democratic Party could not be pressured to secure the interests of workers. Its liberal wing, headed by Senator Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts, played a critical role in the rollback of wages and conditions. It was Kennedy who led the push for the deregulation of the trucking and airline industries, the consequences of which contributed to driving the PATCO workers into struggle.

Carter administration officials later publicly took credit for the PATCO union-busting operation. The plan was devised in early 1980 by Langhorne M. Bond, Carter’s appointee to head the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and Clark H. Onstad, chief counsel to the FAA and also a Carter appointee. As early as 1978, Onstad began to work up plans for criminalizing a PATCO strike in discussions with Philip B. Heymann, Carter’s assistant attorney general in charge of the Criminal Division of the Justice Department.

“Incredibly detailed planning [went] on for more than a year because we just knew the strike was going to happen,” Onstad told the New York Times in the midst of the strike. The Times remarked, “Reagan administration officials enthusiastically polished and put into effect the plans first drafted in the Carter Administration.”

These schemes could not be explained on a purely fiscal basis. As PATCO workers noted, there would be enormous costs associated with training thousands of new controllers, to say nothing of the damage to the economy resulting from the inevitable restriction of commercial flights. The grievances of the controllers, who were generally portrayed in the media as privileged, pampered and arrogant, were widely shared and involved genuine safety concerns for fliers.

Though PATCO controllers were paid more than most US workers, they were highly skilled. They performed a job that entailed a high degree of stress and carried immense responsibilities for the safety and lives of others.

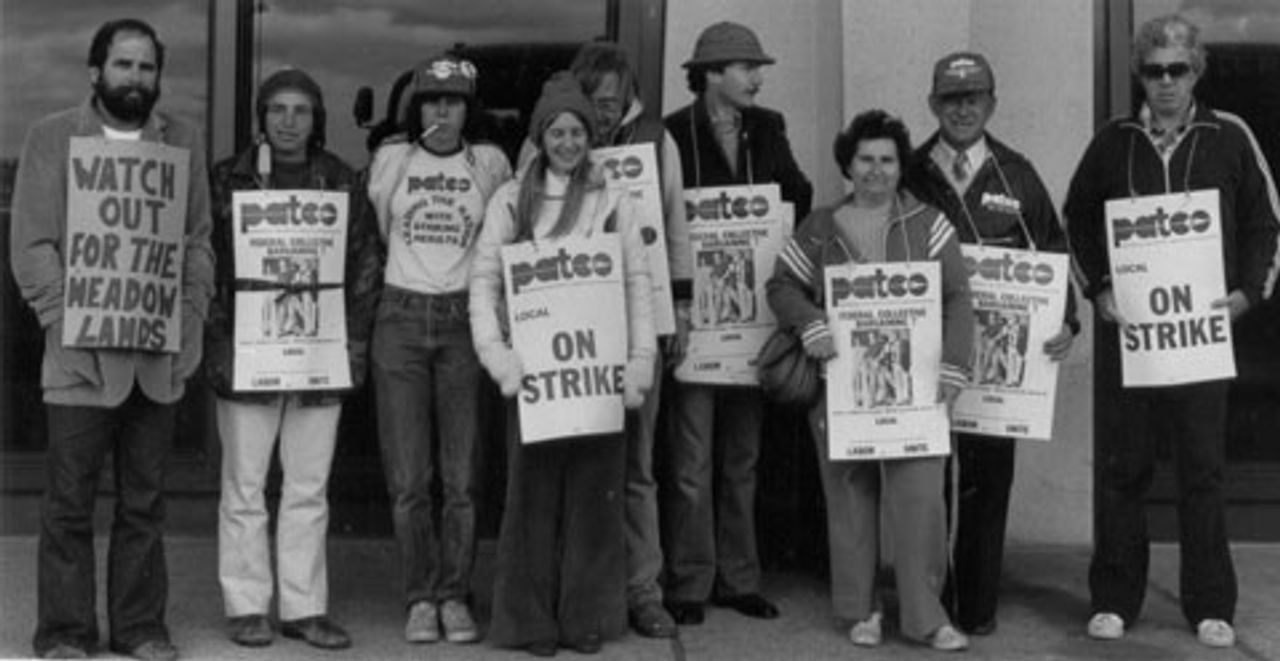

PATCO pickets

PATCO picketsIn discussions with Bulletin reporters, PATCO strikers again and again said they were compelled to strike because understaffing and other FAA policies had raised the stress level of their jobs to the breaking point. Workers raised grievances over the length and intensity of shifts, which needlessly added to their occupational stress.

Grueling conditions led many to early retirement over health issues. “Our job is separating airplanes,” Detroit Metropolitan Airport controller John Neece told the Bulletin. “We keep them from colliding. You never really get used to it. … In the 12 years since I’ve been here, I’ve seen one guy go out on a normal retirement and 20 go out with medicals—bad ulcers, nerves, heart problems. I’m 38 now and the chances are I won’t make it until retirement. If you go out on medical they just give you 40 percent of your pay and say get the hell out. … What we’re doing is like three-dimensional chess. But in this game, when it’s checkmate, you’re gone.”

“We have no breaks,” Oakland air traffic controller Tom King told the Bulletin. “We work eight hours straight. We just eat at the scope. We haven’t had a heater or an air conditioner at all.”

“I know one guy in eight years who has retired normally from here,” said another Detroit striker, Bud Pierce. “When I get home at night it takes me two or three hours before I can unwind. They rotate shifts so that you can leave here at 10 at night and have to be back at 7 AM the next morning.”

To be continued