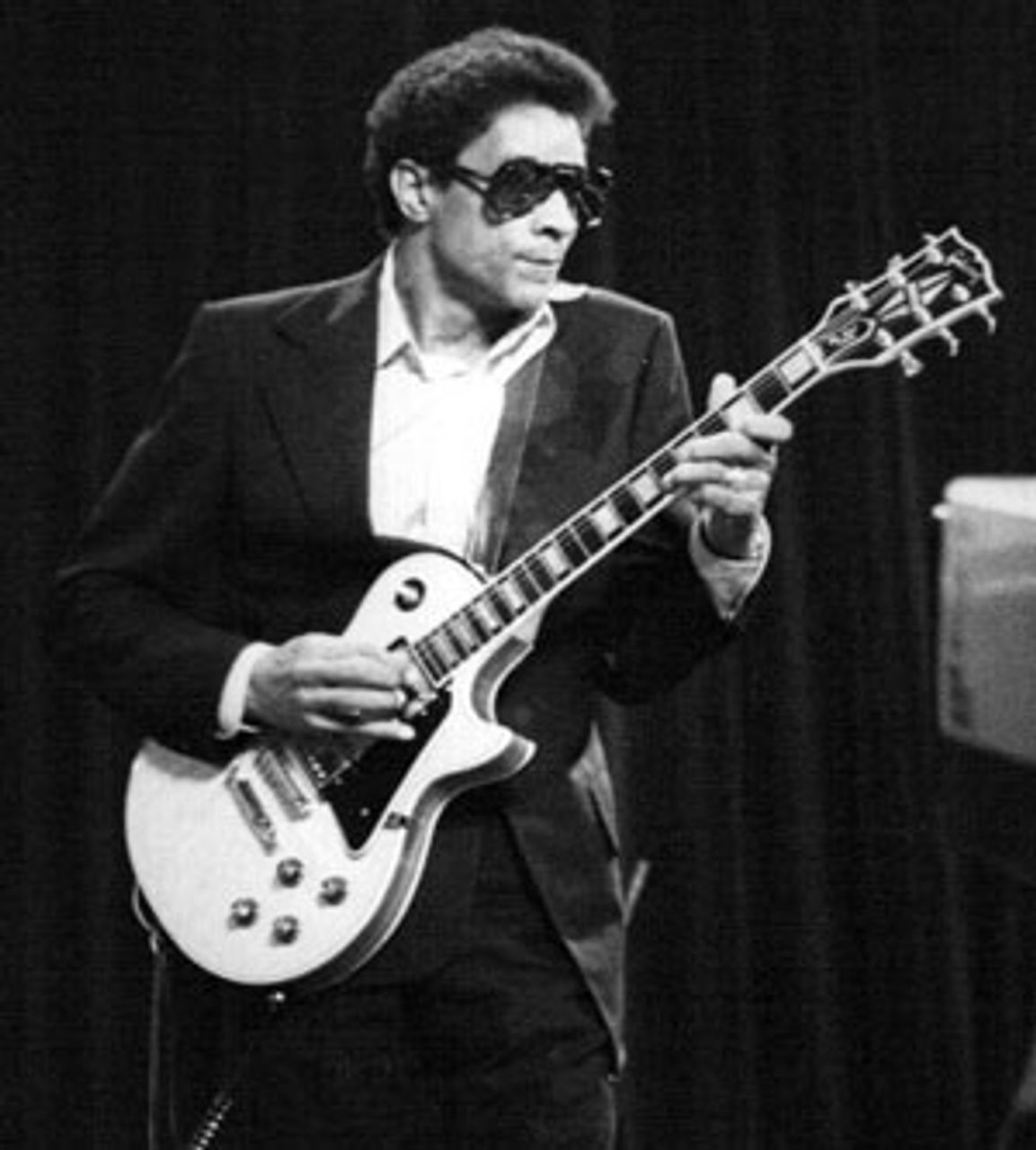

Hubert Sumlin playing the Jazzfest in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, July 2006 [Photo: Xopher Smith]

Hubert Sumlin playing the Jazzfest in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, July 2006 [Photo: Xopher Smith]The guitarist Hubert Sumlin, who died last month at the age of 80, was one of the most influential contributors to the Chicago electric blues boom of the 1950s. His work with Howlin’ Wolf contributed much to the sound associated with the Chess record label, which did so much to define the genre.

Sumlin’s striking guitar playing was also a major inspiration for younger rock musicians turning to the blues in the 1960s. Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page said he loved Sumlin’s playing because “He always played the right thing at the right time”. It is in part thanks to the respect of these musicians that influential sidemen like Sumlin and the pianist Pinetop Perkins, who died earlier in 2011, have been recognised and celebrated. This patronage encouraged Sumlin’s solo career after the death of Wolf, his mentor and collaborator for over 20 years.

Wolf’s attitude to Sumlin was almost paternal. Sumlin was (wrongly) identified as his son in Wolf’s funeral programme. Wolf unquestionably nurtured Sumlin’s playing from quite an early age. “Hubert was Wolf and Wolf was Hubert,” Sumlin once said. “That’s the way it was. He wouldn’t go nowhere without me and I wouldn’t go nowhere without him”.

Hubert Sumlin in 1978

Hubert Sumlin in 1978Hubert Sumlin grew up in in the heartlands of Mississippi Delta blues, the son of a tenant farmer. Born in Greenwood, Mississippi, and raised in Hughes, Arkansas, he began playing guitar at the age of 6. He had early aspirations to be a jazz player, and began playing blues around the West Helena area in the company of the harmonica (harp) player James Cotton. Cotton, who is still playing, later spent 12 years in the band of the other towering figure of 1950s Chicago blues, Muddy Waters.

Both Sumlin and Cotton, from a poor rural area, were supported and encouraged by older musicians. Cotton spent a lot of time with Sonny Boy Williamson II (Rice Miller), who also taught Wolf to play harp.

The defining moment for Sumlin came when they checked out a local club performance by Wolf. Sumlin was too young to get into the club, so he climbed onto some boxes to look through a window. When the unsteady boxes collapsed, he fell into the room, landing on the singer. Wolf drove him home after the show and asked Sumlin’s mother not to punish him. “I followed him ever since”, said Sumlin.

Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Arthur Burnett) was a remarkable performer. He was a big man, standing 6’6” and weighing 300 pounds, and footage of his live performances shows a compelling and ferocious intensity. He had a huge and powerful voice, raucous, bellowing and tender by turn. The critic Charles Shaar Murray once described it as like “a hurricane coming through a letter box”.

Wolf always came across as more of a force of nature than the rather suave Muddy Waters. He frustrated Willie Dixon, whose brilliant songs were a major component of the Chess package, by not being as adept with sophisticated lyrics as Muddy. Sonny Boy Williamson, who was related to him by marriage, recorded a hilarious impression of his fierce but basic harp playing in “Like Wolf”.

There was nothing unsophisticated about this intensity, or the bands that played behind him. He seems always to have been capable of transfixing audiences even as his band rocked them. In 1951-1953, he was recording in Memphis at Sun Studios with the guitarists Willie Johnson and Pat Hare (both of whom later worked with Muddy Waters in Chicago). Exploiting the possibilities of amplification, they produced a raucous and distorted tone to their swinging lines. It was a new sound, one that was emerging across America.

Although Willie Johnson did not initially accompany him, Wolf’s 1953 relocation to Chicago was inevitable. Chicago was the focus of the burgeoning electric blues scene, and the sound that Wolf had produced in Memphis was being further explored on the club circuit and recording studios there, by musicians such as Little Walter, Robert Lockwood, Willie Dixon and, notably, Muddy Waters.

Sumlin had sometimes been allowed to sit in with Wolf’s band when they played in the south. Early in 1954, Wolf sent for him in Chicago. Sumlin moved north and settled into the band as a permanent fixture. Starting as a second guitarist, he became the mainstay of Wolf’s sound for the rest of the singer’s life.

Sumlin brought an angular and spiky funkiness to his riffing, and a sharpness of tone and attack to his lead lines. With a guitar in his hands, the rather shy Sumlin became an acute counterpoint to the dominating Wolf. On masterpieces like “Spoonful”, “Killing Floor” or “Smokestack Lightnin’ ” his ominous and unpredictable guitar cuts through the arrangement, building the tensions and intensity of the vocal line. It is a ferocious sound. Wolf’s biographer Mark Hoffman described the musical combination as “like gasoline and a lit match”.

It was a guitar sound he acquired the hard way, through his volatile relationship with Wolf. Wolf once ordered Sumlin off the bandstand because of the volume of his amplifier, telling him to take lessons from a local classical player and “throw that pick away”. Sumlin abandoned the use of a plectrum, and his finger-picking technique added greatly to the sound he achieved. It improved his playing, he said, by helping him “feel the soul and the pain”. Saxophonist Eddie Shaw, who played alongside Sumlin for 13 years, said this resulted in “a different sound that other guys couldn’t get”.

The volatility of their relationship saw Sumlin and Wolf come to blows more than once. When Sumlin arrived after a gig had finished, Wolf dragged him from his car and knocked him down a hill. Some days later, Sumlin, now missing two front teeth, turned up at a Chicago club and punched Wolf, knocking out some of his teeth in turn (although he was later to deny that he could have done any such thing to such a big man). Describing the violence and intensity of their relationship in 1994, Sumlin said, “None of it mattered: we always got right back together”.

Sumlin remained with Wolf almost constantly until the singer’s death in 1976, apart from brief spells with Eddie Taylor and Muddy Waters. Taking the latter gig, which paid better than his regular work, resulted in the two giants of Chicago blues squaring off over his place in their band.

As rock bands in the late 1960s began to cover the ’50s Chicago repertoire, and as the city’s music scene began to change, there was pressure on blues artists to move into unfamiliar areas. Seeing the success of Jimi Hendrix and Cream’s covers of blues standards, Chess encouraged both Muddy and Wolf to make rock/psychedelic albums. Wolf’s was a particularly unhappy experience, possibly because he hated it so much. (He told guitarist Pete Cosey, who would later work with Miles Davis, “Why don’t you take them wah-wahs and all that other shit and go throw it off in the lake.”) Sumlin remained by his side throughout.

More successful was an album made in London with Eric Clapton, Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts, amongst others. By this stage, Sumlin was widely recognised and praised by younger musicians, many of whom had covered versions of Wolf’s songs like “The Red Rooster”. Clapton had been booked to play on the album, but refused to appear unless Sumlin was there.

Wolf was already in ill health by this time, and Sumlin took his death hard. He played until 1980 with The Wolf Pack, members of Wolf’s band led by saxophonist Eddie Shaw. He could not depend on any royalties for his remarkable work, and was forced to continue freelance work.

He eventually became a bandleader, although he was not a natural front man. His unprepossessing singing voice suffered further from serious respiratory disease—he was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2002, and had a lung removed two years later—but his primary interest remained the guitar. There are moments on the later solo albums where his guitar playing leaps into life again, thanks in part to the support of fans like Clapton and Keith Richards. Richards financed some of Sumlin’s later recording sessions, and contributed extensively to his medical bills after his 2002 cancer diagnosis. His later work emphasises the brilliance of his collaborative work as Howlin’ Wolf’s right-hand man in shaping a whole musical idiom.