The US Labor Department on Friday reported that the US economy added a mere 120,000 net jobs in March, less than half the average monthly payroll growth over the previous three months. The jobs figure was far below the 200,000-plus predicted by economists and pointed to a stagnating or worsening labor market in the coming months.

The private sector added a net 121,000 jobs, while government positions declined by 1,000.

It takes at least 150,000 net new jobs each month just to keep pace with normal population growth, and it is estimated that the economy must add 13 million jobs over the next three years—362,000 each month—to bring unemployment down to 6 percent. Even the average net gain of 240,000 jobs per month over the December-February period, hailed by the White House and the media as proof of an accelerating economic recovery, fell short of the rate of job-creation in previous recoveries and was well below the rate needed to end mass unemployment.

The March jobs figure was the lowest since October of last year and marked the first month with a net payroll increase below 200,000 since November.

The official jobless rate ticked down from 8.3 percent in February to 8.2 percent, but this decline also reflected a deterioration of the labor market. The rate went down not because more people obtained jobs, but because many more people dropped out of the labor force.

The number of people with a job fell by 31,000 and the number of people looking for a job fell by 133,000, resulting in a total decline in the labor force of 164,000 people. Since the government calculates the jobless rates as a percentage of those either working or actively looking for work, millions of so-called “discouraged workers” who have abandoned the search for employment are not counted. The official unemployment rate can decline even though the ranks of jobless workers increase.

Analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistic’s Current Employment Statistics public data series

Analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistic’s Current Employment Statistics public data series Source: Economic Policy Institute

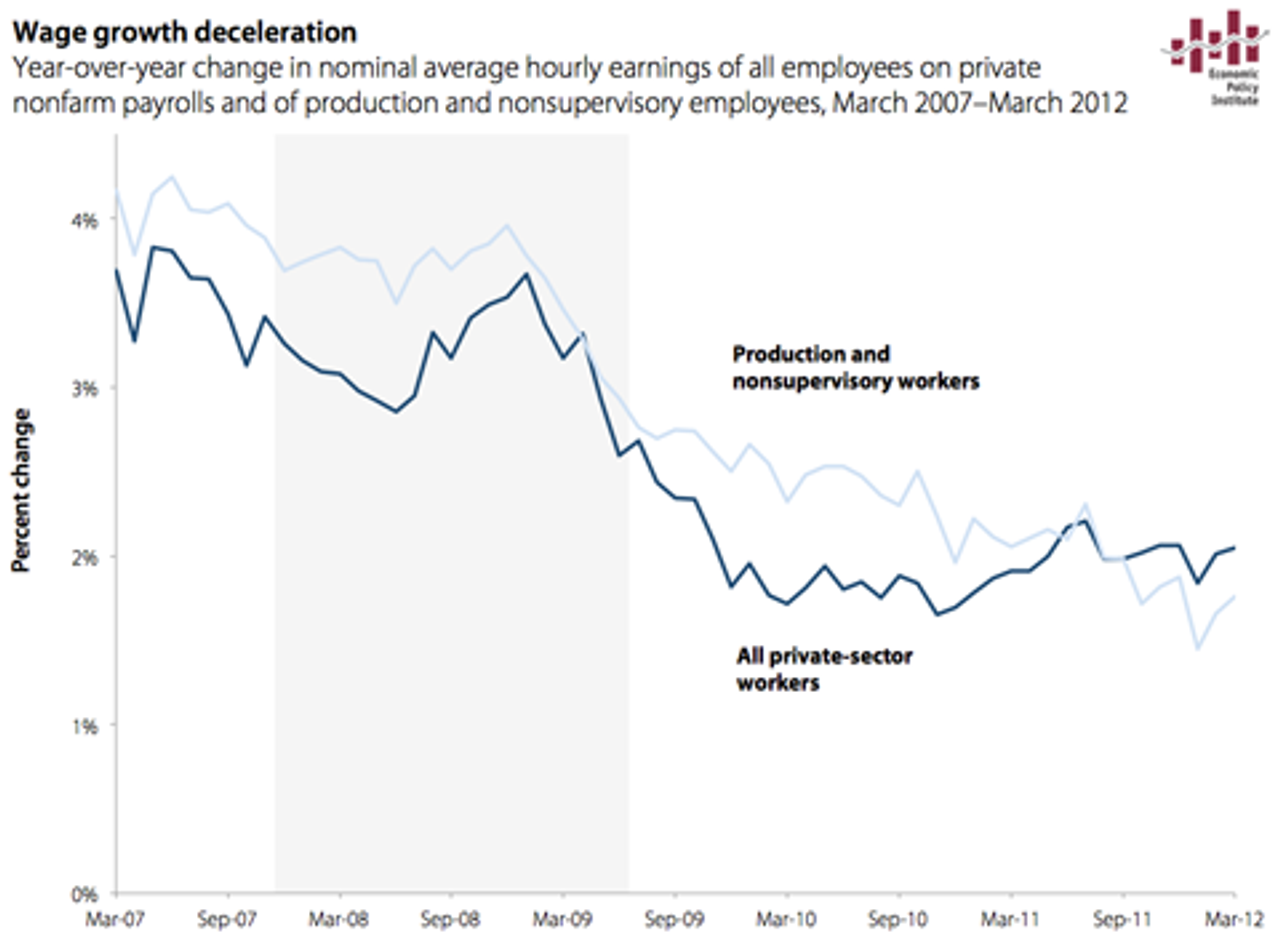

Note that the decline in wage growth for production and nonsupervisory workers has continued after the official end of the recession (shaded area).

The labor force participation rate, a more accurate reflection of the jobs crisis, declined to 63.8 percent. Except for January’s 63.7 percent, the March figure was the lowest level since 1983. The share of the population with a job also fell, hitting 58.5 percent in March. This compares to 62.7 percent at the official start of the recession in December 2007 and is the lowest since the mid-1980s. (According to the government, the recession ended in June of 2009.)

Not only are there 12.7 million people counted by the government as unemployed, and nearly 23 million (14.5 percent) counted as underemployed (unemployed, working part-time but wanting a full-time job, or available for work but no longer looking), there is a growing number of long-term unemployed who are not counted in any of the government indices.

Over 40 percent of the unemployed in March—5.3 million people—had been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. This compares to the previous record rate of long-term joblessness over the past six decades of 26 percent, in June of 1983. The average time out of work for those counted as unemployed was 39.4 weeks, a near record.

The March report also showed a decline in hours worked and workers’ earnings. Average weekly hours worked fell to 34.5 from 34.6, and average weekly earnings fell to $806.96 compared with $807.56 a month earlier.

Average hourly wages for production and non-supervisory workers increased by 3 cents in March, representing a 1.8 percent annualized growth rate over the last year. This is below the rate of inflation and far below pre-recession wage growth rates.

The official unemployment rate remains particularly high for young people and for African Americans and Hispanics. In March, unemployment was 16.4 percent among workers age 16-24, and 25 percent for 16-19 year olds. It was 14.0 percent for African Americans and 10.3 percent for Hispanics.

The March jobs figures show, as Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke indicated in a speech last week, that the recent payroll increases reflected a slowdown in layoffs rather than a substantial increase in hiring. Hiring is still running 20 percent below pre-recession levels. The decline in the nominal jobless rate from 9.1 percent last August to 8.2 percent cannot be sustained at the current anemic rate of economic growth.

But even on the layoff front, mass job cuts continue. On Wednesday, Yahoo announced it was laying off 2,000 workers, or 14 percent of its work force. This followed last week’s announcement by the retail electronics chain Best Buy that it was closing 50 stores and laying off hundreds of employees.

In the face of the disastrous March employment report—itself a pale reflection of the social devastation facing millions of Americans—President Barack Obama hardly bothered to conceal his indifference. Speaking Friday at a White House “Forum on Women and the Economy,” Obama said, “So we welcome today’s news that our businesses created another 121,000 jobs last month, and the unemployment rate ticked down.” Oozing complacency, he went on to add that “there will still be ups and downs along the way,” and that “we’ve got a lot more work to do.”

Labor Secretary Hilda Solis, in a similar vein, declared, “Some months we are seeing tremendous job gains, while other months we are seeing more modest gains. But the trend line is clear. Our economy is growing, and our recovery is durable.”

Making clear that the administration has no intention of doing anything to seriously address the jobs crisis, the director of the White House National Economic Council, Gene Sperling, said, “The economy’s on a much better trajectory than it was when the president came to office and we just have to keep at the policies and keep doing the things that are helping the economy recover.”

What the administration and both corporate-controlled political parties are, in fact, doing is using the supposed “recovery” as a pretext for slashing unemployment benefits. This is being done to help big business use mass unemployment to gut the wages, benefits and working conditions of the working class. Last week Georgia became the latest state to reduce the duration of jobless benefits, cutting it from 26 weeks to between 14 and 20 weeks. It joined ten other states that have cut eligibility for jobless pay or the duration of benefits.

In February, the White House and congressional Democrats struck a deal with the Republicans to slash the duration of federal extended unemployment benefits, reducing it from 99 weeks to as low as 63 weeks, depending on the jobless levels of individual states.

The modest increase that has taken place in manufacturing jobs is based almost entirely on the destruction of wages and benefits. US auto companies have carried out some hiring and returned to profitability following the halving of wages and gutting of benefits for newly hired workers imposed, with the support of the United Auto Workers union, by Obama’s Auto Task Force in 2009. This set the stage for a massive assault on wages across the economy, with workers frequently forced to accept new jobs paying half the wages of the jobs they lost.

At the same, with complete cynicism, Obama continues to extend windfalls to business in the name of “job-creation.” On Thursday, the day before the jobs report, Obama signed the so-called JOBS Act at a White House ceremony attended by leading Republican legislators, who joined with the Democrats in passing the measure. The Jump-Start Our Business Startup (JOBS) Act does not create a single job. Instead, it rolls back financial reforms that were enacted following the Enron debacle a decade ago, making it easier for banks and speculators to swindle investors and the public.

Following the sweetheart settlement engineered by the Obama administration in February with five major banks guilty of wholesale mortgage-related fraud, the banks are preparing to sharply increase the rate of home foreclosures. “I would put money on 2012 being a bigger year for foreclosures than 2010,” Mark Seifert, the head of a counseling group in Ohio, told the Washington Post.

The author also recommends:

The Obama recovery

[28 March 2012]