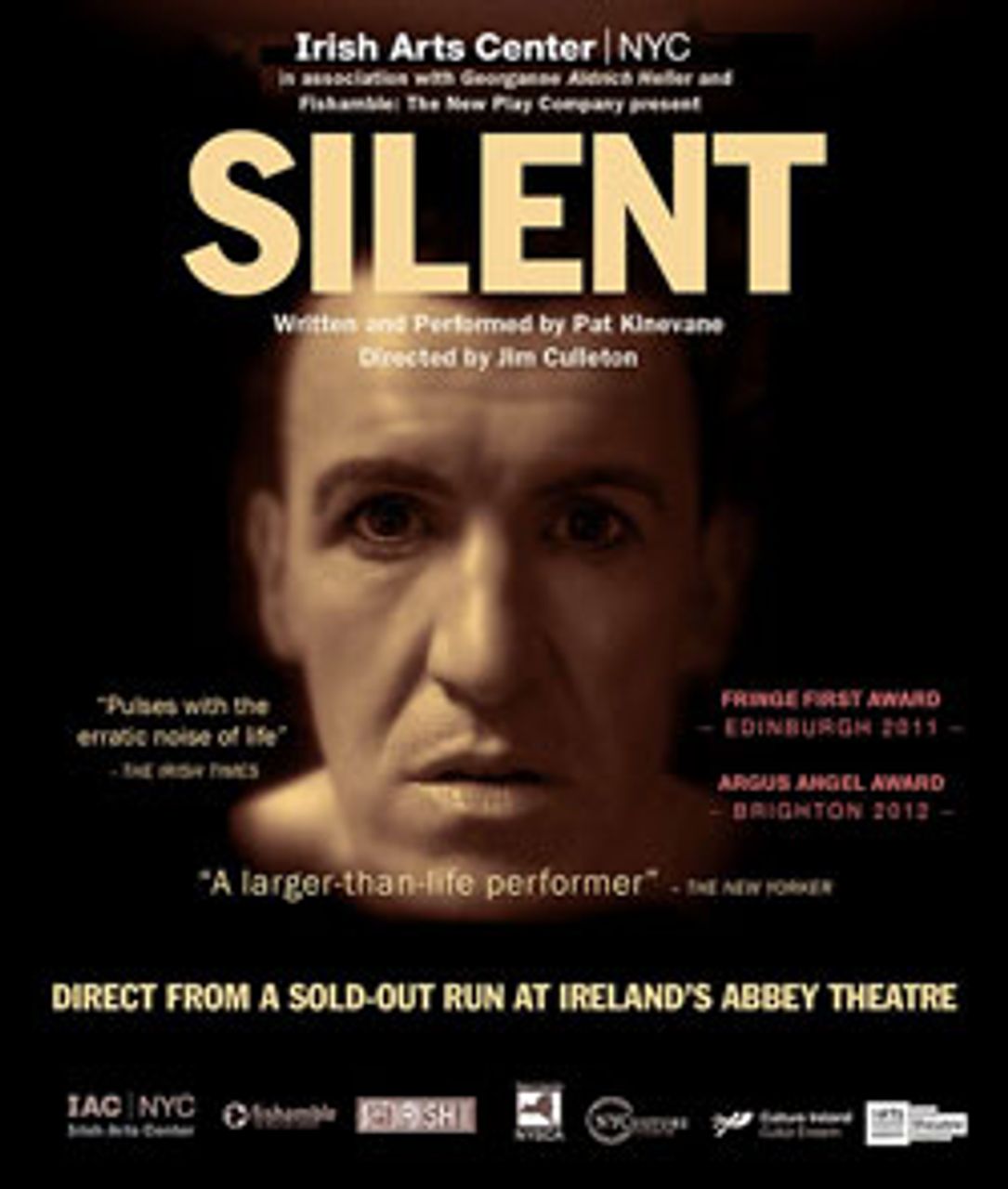

Written and performed by Pat Kinevane, directed by Jim Culleton of Fishamble Theatre Company, September 6-23, at the Irish Arts Center, New York City.

Presented as part of the 1st Irish Theatre Festival: September 3-October 1.

“If anyone asks, I’m not here. Right?” So begins the earnest and ultimately tragic tale of Tino McGoldrig the homeless protagonist in writer-performer Pat Kinevane’s 80-minute one-man show, Silent. The piece is part of the 1st Irish Theatre Festival in New York City, which runs until October 1.

“If anyone asks, I’m not here. Right?” So begins the earnest and ultimately tragic tale of Tino McGoldrig the homeless protagonist in writer-performer Pat Kinevane’s 80-minute one-man show, Silent. The piece is part of the 1st Irish Theatre Festival in New York City, which runs until October 1.

Cork-born author Kinevane clearly has genuine empathy for characters who don’t live up to society’s accepted norms. Two years ago, Kinevane successfully performed his previous solo effort, The Forgotten, in New York to wide critical acclaim. That piece focused on four “forgotten” characters living in a home for the elderly.

And as the opening line of Silent suggests, Tino McGoldrig is also a figure destined to be abandoned and forgotten, a man who feels like he simply no longer exists. The central character narrates the story from his “home,” a Dublin sidewalk, indignantly raging at the cruel blows life has dealt him, while weaving back and forth between the past and present.

The name “Tino” is the product of his father’s affection for silent movie star Rudolph Valentino. Tino’s deceased brother Pierce, we quickly discover, was apparently as attractive as the silent movie star. And indeed an integral part of the play is Tino’s enormous guilt over the suicide of his homosexual sibling in the small town of Cobh, County Cork.

Creators Kinevane and director Jim Culleton wear the “silent” symbolism very much on their sleeves throughout the production. Sometimes successfully, on other occasions, not so much.

Admitting one was gay in a rural, working class town in Ireland in the 1980s was no doubt challenging, to say the least, and Kinevane for the most part does very well at depicting the difficulties his brother faced.

At home, for example, Pierce receives little sympathy. His mother coldly and consistently refers to him as a “poofter,” among other epithets. Kinevane’s characterization of the brothers’ cynical mother is comically well-executed, although at times the representation veers into the one-dimensional. Outside of the home the challenges continue as Pierce is maligned by the villagers for his extravagant dress and generally eccentric behavior. Tino’s “silence” is referenced throughout these scenes. “Why didn’t I speak up? Why didn’t I defend him?” These questions recur in McGoldrig’s storytelling.

We are then subjected to several “silent” sequences revealing Pierce’s tortured adolescence, as he attempts and fails to end his life numerous times, before finally succeeding. Here Kinevane and Culleton resort to silent film gimmickry. Kinevane plays the various characters while we hear Tino’s voice commenting on his brother’s suicide attempts. These scenes are overly elaborate and grow tiresome.

The same can be said of the dance sequences the performer engages at various points in the play as he attempts to recapture Valentino’s screen essence. No easy feat, and I’m afraid to say Kinevane fails here. He was not aided by what can only be described as some sloppy direction from Culleton. The performer on too many occasions is left to meander aimlessly from topic to topic both physically and verbally. The scene transitions are generally poor.

The major strength of the play is Kinevane’s authentic depiction of how a homeless figure can be callously mistreated by sections of the middle and upper classes. This is very much in evidence in a poignant scene where a group of drunken rugby fans exit a nightclub late at night and, on seeing Tino, urinate on the homeless man while laughing grotesquely. Tino, helpless, remains silent. This moment was moving and never descended into self-pity.

On the other hand, the biggest weakness of the production is its reluctance to fully engage in the broader picture. The writer has chosen for the majority of the piece to focus on the purely psychological aspect of Tino McGoldrig’s predicament.

Of course, there are particular factors, including psychological ones, in each case of homelessness, but the substantial rise of this social blight in every major city in Europe and America obviously speaks to a social process and crisis.

As of September, the central statistics office announced that there were up to 3,800 homeless people in Ireland. As of June, it was recorded that there were 44,400 homeless people in New York City. Both figures are likely to be underestimations.

In a post-show talk-back, Kinevane stated that the idea for Silent came about as a result of his interactions with the homeless community while in New York two years ago. Given that entirely legitimate starting-point, it is a shame he and director Culleton did not dig deeper into the plight of individuals such as Tino.

A scene in the piece where such engagement could and perhaps should have occurred is one in which Kinevane satirizes an Irish cabinet minister. Tino cleverly lampoons the political figure, re-enacting a commercial released on Irish national television. The latter was supposed to indicate how deeply the Irish government cared for the homeless. As Tino wonderfully illustrates, the commercial, however, is nothing more than a condescending appeal to the thousands of homeless people in Ireland to “look after yourself.” This line is repeated over and over again by the politician in the commercial. Although Kinevane makes this brief scene amusing, it felt like a missed opportunity to engage in wider issues.

The same criticism can be leveled at a scene in which McGoldrig rails at a random passer-by: “You’re just two paychecks away from this.” McGoldrig’s point is well-taken, but such moments, unfortunately, seem to come somewhat out of the blue as Kinevane has spent so much of the 80-minute play concentrating on Tino’s brother and making cheap gags about the village idiots Tino and Pierce encountered in their youth.

That being said, it is refreshing to see a contemporary playwright-performer attempt to engage with serious problems and Kinevane deserves credit for this. Fishamble Theater Company have successfully toured this production all summer long throughout Ireland, including sold-out runs at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin and the Cork Midsummer Festival. During this time there have apparently been ongoing updates to the script. This indicates a healthy desire on Kinevane’s part to grow as a writer and improve on this particular narrative.

A more thorough engagement in the conditions that homeless people are faced with day-to-day, and the circumstances out of which homelessness as a social problem arises, would unquestionably make the production stronger. One hopes that Kinevane may in time reach such a conclusion.