This is the third of a series of articles devoted to the recent Toronto film festival (September 6-16). Part 1 was posted September 22 and Part 2 on September 26.

The 2012 Toronto film festival screened numerous serious documentaries and docu-dramas, reflecting as a totality and in incipient form, the impact of the current social crisis and the increasing resistance of the global working class. Even when historical events are under consideration, the treatment in many cases is driven, one senses, by present realities and concerns.

However, that the film directors and writers are responding to important events does not guarantee that they have absorbed the truth of the latter or even possess an intuitive grasp yet of the depth of the crisis, its horrific social and psychic consequences or revolutionary implications.

In most cases, this problem finds expression in a limited, sometimes myopic, treatment of significant subject matter. It is worth posing at the outset a complex and not always easily answerable question: at what point does naïveté pass over into deliberate evasion?

In The Central Park Five, for example, renowned documentarian Ken Burns and his collaborators tend to gloss over the sharpest contradictions of American society and idealize its history. The powerful story of five minority teenagers whose lives were devastated by the New York City police and legal system is treated largely as an aberration, or at least in isolation. Therefore, an opportunity for a broader and deeper look at pervasive social problems threatens to be dissolved in a celebration of the “triumph of the human spirit.”

US filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer’s courageous documentary, The Act of Killing, treats the 1965 massacre of hundreds of thousands of leftists and workers in Indonesia without mentioning, however, the role of American imperialism and other major participants. How much of the truth is lost as a result?

Perhaps most inexcusably, given the present climate, Syrian director Hala Alabdalla’s As If We Were Catching a Cobra offers abstract appeals for “democracy” and carelessly equates the Great Power-backed Syrian opposition with the Egyptian uprising. Here too, the part played by the US and its allies in the events—financing and encouraging the Syrian rebels—is entirely omitted.

Since art is not an arena for half-truths, these various choices have consequences in terms of the forcefulness and persuasiveness of the films in question.

The Central Park Five

The Central Park Five

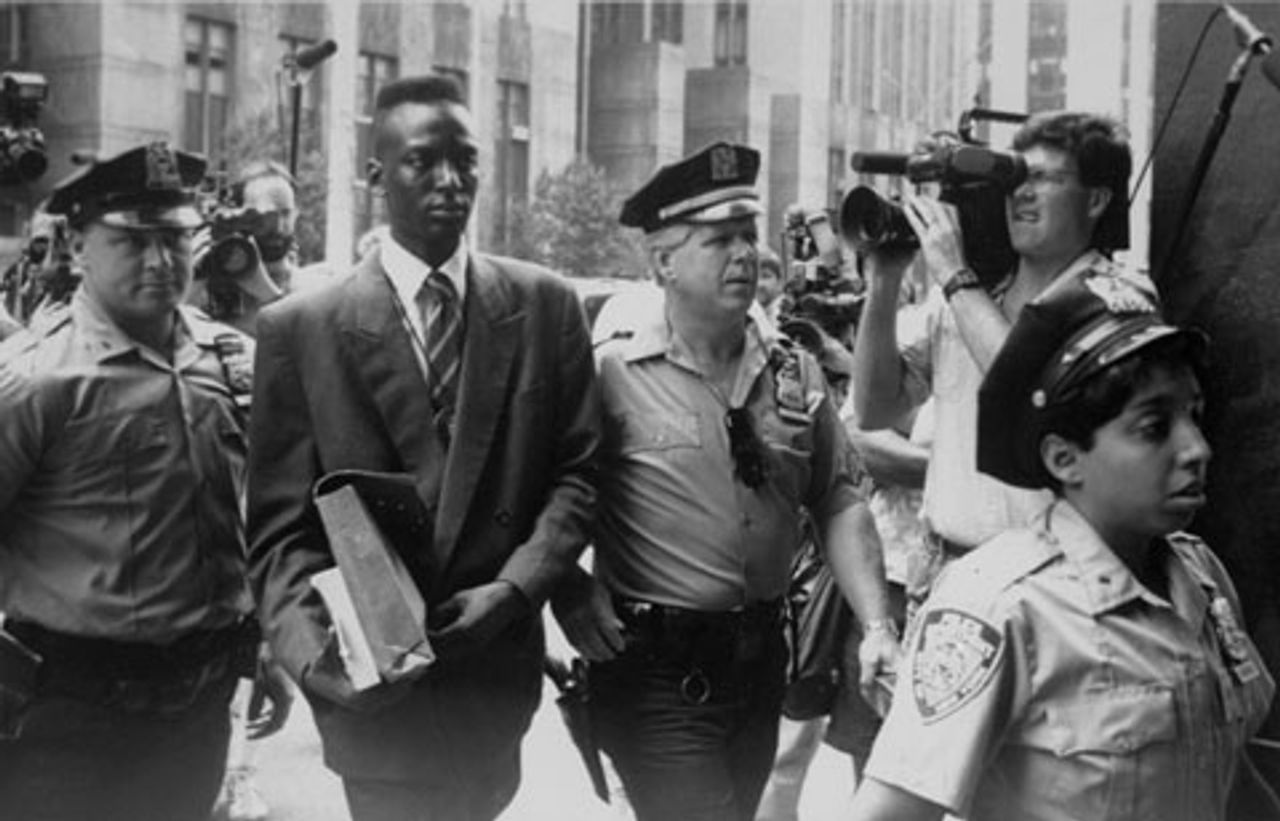

The Central Park FiveIn New York City in 1989, five minority youth aged 13 to 16 were arrested and convicted in the rape and near-murder of a 28-year-old white female investment banker, Trisha Meili, who was jogging in Central Park. The incident dominated the headlines of the tabloids for weeks, as the gutter press took a seemingly golden opportunity to whip up hysteria against black working class youth.

The victim in the assault suffered from memory loss as a result of her injuries and was unable to identify her attackers.

The innocent black and Latino teenagers from Harlem spent between 6 and 13 years in prison before a serial rapist confessed to the crime. Directed and produced by Burns, daughter Sarah Burns, who has written a book about the case, and her husband David McMahon, The Central Park Five chronicles the case, focusing on interviews with the now-adult men who suffered appallingly at the hands of a vindictive and unjust legal structure and media.

At the time of the tragic incident in Central Park, social tensions were high, as deteriorating economic conditions and budget cuts helped generate record levels of violent crime, and the city’s elite was demanding a crackdown.

The Central Park Five

The Central Park FiveFollowing the brutal attack on Meili, a police dragnet against minority youth led to the rounding up of Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise and Yusef Salaam, who “confessed” to the Central Park attack after 14 to 30 hours of aggressive interrogation by police.

The New York media went into a frenzy against the teens, who it claimed were out “wilding,” running in a “wolf pack” after their “prey.” Mayor Ed Koch called the boys “monsters,” claiming that this would be a test case for the death penalty. Real estate billionaire Donald Trump took out full-page ads in all four of the city’s dailies, headlined “Bring Back the Death Penalty, Bring Back Our Police.” New York Times liberal black columnist Bob Herbert penned the expression “teenage mutants.”

Careers in the police department and the prosecutors’ office were made at the expense of the persecuted teenagers. The young men were tried and convicted despite a lack of evidence, including any DNA proof. Burns’ movie offers a sympathetic platform to the victims and their families, whose determined quest for justice contrasted starkly with the callous indifference and criminality of the police, the judicial system, Democratic Party politicians and their media accomplices.

In 2002, based on the confession of Matias Reyes, a judge vacated the original conviction of the Central Park Five. Civil lawsuits filed by the men against the City of New York and the police officers and prosecutors who worked for their convictions remain unresolved.

This is a case absolutely worth revisiting, but the filmmakers’ decision to present it almost entirely in racial terms is an error. The vast prison population in the US, which includes both those who are innocent of the crimes for which they are charged and those whose primary crime is being poor, are victims of the present social inequality and blighted character of American capitalism.

The filmmakers downplay this dominant reality. Says Ken Burns in the movie’s press notes: “This tragedy reminds us how much we struggle to come to terms with America’s original sin, which is race.” The profit system is the original sin, and race is used as one of its preferred means of dividing and conquering. The film itself shows that the political and media offenders are both black and white.

Moreover, the Toronto festival this year also screened the latest installment in the saga of three white Arkansas men, known as the West Memphis Three (West of Memphis, directed by Amy Berg), who as teenagers shared a similar fate to that of the Harlem teenagers. In deliberately narrowing the scope of The Central Park Five, the Burns team implies, by what it leaves out, that the case is an unhappy exception rather than one episode in an ongoing social disaster. The best intentions cannot make up for this sort of social semi-blindness.

The Act of Killing

The Act of Killing

The Act of KillingIn October 1965, one of the greatest defeats and betrayals of the post-World War II period was inflicted on the international working class. Close to one million workers and peasants were slaughtered in Indonesia in a CIA-organized army coup led by General Suharto, which toppled the unstable bourgeois nationalist regime of President Sukarno and established a brutal military dictatorship. The US government, aided by its Australian and British counterparts, helped staged the coup to suppress the revolutionary strivings of the Indonesian masses.

At the time of Sukarno’s overthrow, the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) was the largest such party in the world outside the Soviet Union and China, with nearly 3.5 million members and a youth movement of another 3 million. By the end of 1965, between 500,000 and one million PKI members and supporters had been slaughtered and tens of thousands detained in concentration camps. So massive were the killings that the rivers were clogged with corpses.

The bloodbath and coup in Indonesia were the outcome of the drive by US imperialism to gain control of the natural and strategic resources of the archipelago, known as the “Jewel of Asia.”

Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing is a chilling documentary that involved enticing a group of the 1965 murderers to re-enact their executions in the style of different genres of Hollywood films. They are eager and ghoulish participants. Their re-creations include elaborate sets, costumes and special effects, and take the form of musicals, film noir gangster movies and Westerns.

The film’s production notes explain that when the 1965 coup took place, Anwar Congo—the movie’s central figure—and his cohorts in Medan, Indonesia were promoted from small-time thugs who sold movie theater tickets on the black market to death squad leaders. Congo himself killed hundreds of people. In the film, he and other leaders of the Pancasila Youth paramilitary movement unrepentantly dramatize their murders.

This was a risky venture for the filmmakers and the movie’s Indonesian crew cannot be identified for fear of deadly reprisals. The Act of Killing is remarkable in the way it captures the degraded nature of this backward social layer, the dregs of society.

However, the filmmakers’ wrongheaded emphasis on “collective guilt” and humanity’s “heart of darkness” has the unintended result of obscuring those individuals, organizations and governments concretely responsible for the political genocide in 1965. “Humanity” didn’t commit the crimes—the Indonesian ruling elite and military, in collaboration with the CIA, Pentagon and White House, did.

Furthermore, that the immediate perpetrators of terrible crimes should be exposed—and brought to justice!—is unquestionable. But, again, far bigger operators stood behind them and directed their activities. Anwar Congo and the homicidal paramilitary were nothing more than the small-time henchmen of the Indonesian ruling class and its imperialist backers.

When the makers of The Act of Killing describe the Indonesian population as “docile” and fearful, they also reveal their own ignorance of history and social dynamics. By 1965, Indonesia had a long and bitter history of anti-colonial struggle, and the massive left-wing movement, tragically under the leadership of Stalinist-Maoist forces, demonstrated the wide popular support for the Russian and Chinese revolutions. Opportunities will again emerge for a showdown with the fascist human dust in Indonesia.

As If We Were Catching a Cobra

As If We Were Catching a Cobra

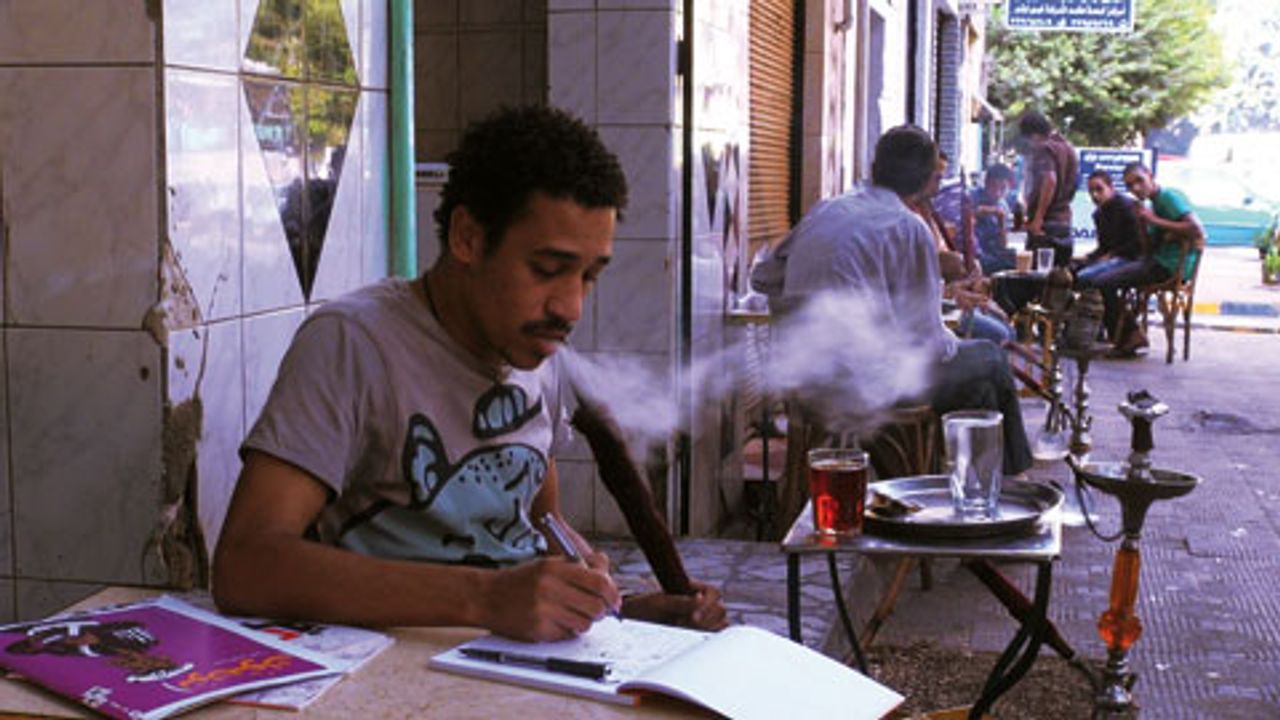

As If We Were Catching a CobraThe caricature art of Syrian and Egyptian oppositionists is the topic of As If We Were Catching a Cobra. Director Hala Alabdalla interviews artists such as veteran caricaturist Mohieddine Ellabbad in Cairo and the renowned Ali Farzat in Damascus. Much of the art is angry and technically impressive. Younger artists are also featured, including Hazem Alhamwi, a Syrian cartoonist who shows the filmmaker drawings he fears to publish.

The movie takes a turn when, in the midst of filming, revolutions break out in Tunisia and Egypt. In Syria, Farzat has been beaten by the authorities and Ellabbad has passed away. A young Egyptian artist is followed in Tahrir Square.

The director and her novelist-essayist friend Samar Yazbek, a major presence in the film, share their confused notions about the anti-Assad cause. It apparently matters not to them from where the opposition is drawn … or who backs it. Alabdalla’s film makes no distinction between the popular revolutionary uprising in Egypt and a Syrian insurgency that has been armed at the behest of Washington via its reactionary Gulf and Turkish allies. This erroneous amalgamation, which permeates Cobra, seriously weakens the film’s investigation into the fascinating traditions of Arab caricature drawing.

After the Battle

After the Battle

After the BattleAn attack by whip-wielding horse and camel riders tearing through Tahrir Square on February 2, 2011, left numerous anti-government protesters dead or wounded in one of the bloodiest days of the revolt that ended Hosni Mubarak’s presidency.

Among the attackers were riders from Nazlet El-Samman, a 19th-century Bedouin community at the foot of the Giza pyramids, who were accused of being paid to start the riot. It turned out that the Bedouins were unarmed and that marksmen on top of buildings in the Square shot the protestors. The snipers have never been identified, but it was subsequently established that the former secretary-general of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party and other parliamentarians were involved.

Egyptian director Yousry Nasrallah has developed a sensitive narrative that exposes the Bedouin community’s innocence in “The Battle of the Camels,” as well as its struggle to make a living under conditions in which the onset of the so-called Arab Spring drove tourism away. This is reinforced by recurring images of a wall erected during the Mubarak days, separating the Bedouins from their beloved pyramids.

The movie centers on the relationship between anti-Mubarak activist Reem (Menna Chalaby), a divorcee from an upscale part of Cairo, and Mahmoud (Bassem Samra), a horseman living in poverty with his family in Nazlet El-Samman. He was one of the Bedouins who attacked the Tahrir Square protestors, an event that continuously replays on television news broadcasts. “The Battle of the Camels” has also brought him shame and humiliation. Diverse political concerns, including women’s rights and class issues, are broached in the collisions between Reem and Mahmoud.

After the movie’s festival screening, Nasrallah explained in a question-and-answer session, that the wall was the way in which the government hid the poor from the tourists. The director said that Mrs. Mubarak forced the Bedouins to leave, replacing the village with tourist hotels, thereby destroying the Bedouins’ livelihood in favor of big business.

Commenting on the present situation in Egypt, Nasrallah said: “The one thing that has been proven by the revolution is that human rights is a universal demand. Mubarak’s party was replaced by the Muslim Brotherhood, who transformed the state apparatus into their own apparatus. Egyptians will not accept that. We’re not just patient, we’re subversive.”

To be continued