A Free Soul

A Free SoulForbidden Hollywood Collection, Volume Two is the second of three pre-Production Code collections from the TCM (Turner Classic Movies) Archives devoted to films released after the adoption of the Production Code (by the film industry itself) in 1930, but before its strict enforcement four years later.

The Code prohibited honest treatment of sexuality, profanity, ridicule of the clergy, etc., and, generally, demanded conformist and reverent attitudes toward America’s institutions. Filmmakers in the US were obliged to contend with and navigate around the Production Code for the next three decades.

None of the five films in this collection displays the brazen defiance of the Code found in Volume One’s Red-Headed Woman (Jack Conway). However, women struggling against the established class structure informs all five of the selections, with several of the actresses delivering inspired performances.

Night Nurse

Night NurseWilliam Wellman’s Night Nurse is the collection’s most daring and successful movie.

Jobless and lacking a high school diploma, Lora Hart (Barbara Stanwyck) becomes a “probationer” (a nurse in training) at an urban hospital where she and roommate nurse B. Maloney (Joan Blondell) endure a number of grueling on-the-job tests—lightened by sight gags, wise cracks and the presence of a bootlegger named Mortie (Ben Lyon)—before graduating and becoming full-fledged nurses.

The second half of the movie takes on a more somber tone when Lora and her fellow nurse are hired to provide home care for two young children. Lora discovers she and Maloney are caught up in a con job to steal the trust fund of the children’s mother (and in the process kill the youngsters), and, after surviving several physical assaults by hired thug Nick (Clark Gable), she gains the courage to confront the perpetrators and save the children.

Wellman’s use of a moving camera and sound boom (he was one of the first Hollywood directors to do so) makes the audience feel like eavesdroppers on reality instead of a movie.

Joan Blondell is excellent as the tough (but vulnerable), street-wise sidekick, a role the actress perfected during her career. In the more serious portion of the movie, the remarkable Stanwyck reveals an early ability to draw on her painful childhood and adolescence to uncap the emotional volcano just below her calm, even subdued exterior.

Gable plays the malevolent Nick with a power and emotional rawness he would rarely unleash again. Sadly, for Gable and the cinema, the “good side” of Gable’s character in A Free Soul (also released in 1931) found so much favor among the moviegoing audience that Hollywood hardly ever allowed him to be so “raw” again.

A Free Soul, directed by Clarence Brown and taken from Adela Rogers St. John’s novel of the same name, features a sterling cast largely undone by a traditional plotline.

Jan Ashe (Norma Shearer), the liberated daughter of a successful but alcoholic lawyer father, Stephen Ashe (Lionel Barrymore), is engaged to Dwight Winthrop (Leslie Howard). The latter is too fawning for her taste, and she has a change of heart when she encounters mob chieftain Ace Wilfong (Gable).

Discouraged about Ace by everyone around her, Jan of course becomes even more attached to him and, in fact, rushes to his side. However, Ace demands she marry him immediately and begins roughing her up. At this, she runs away and learns that her father was right and that Dwight is willing to fight for her love.

Shearer once said, “I can’t do the [Greta] Garbo or [Marlene] Dietrich thing.” She was right about this. Whereas Garbo’s and Dietrich’s characters were often inscrutable and complicated, Shearer tended to play the emotionally open “society women” in pre-Code films.

Her portrayal of the liberated Jan is convincing without going overboard. She clearly conveys the sense that the upper-class, rule-bound world can’t fulfill her needs; and while she tells Ace he’s “a new kind of man in a new kind of world,” she has no trouble stopping his advances when he’s gone too far.

Barrymore as Ashe is both touching and frustrating, and Gable offers a seamless transition from the likable masculine figure with rough edges of his trial (a persona he would inhabit for the rest of his career) to the possessive, brutal thug at the end.

The performances are undermined, however, by the message that a woman should not marry beneath her class. Shearer’s chastened Jan seems more confused than resolved upon her return to her “class,” and with good reason. Even in the act of proving his love for Jan, Howard’s Winthrop comes off as a martyr instead of the self-assured man she’s been looking for.

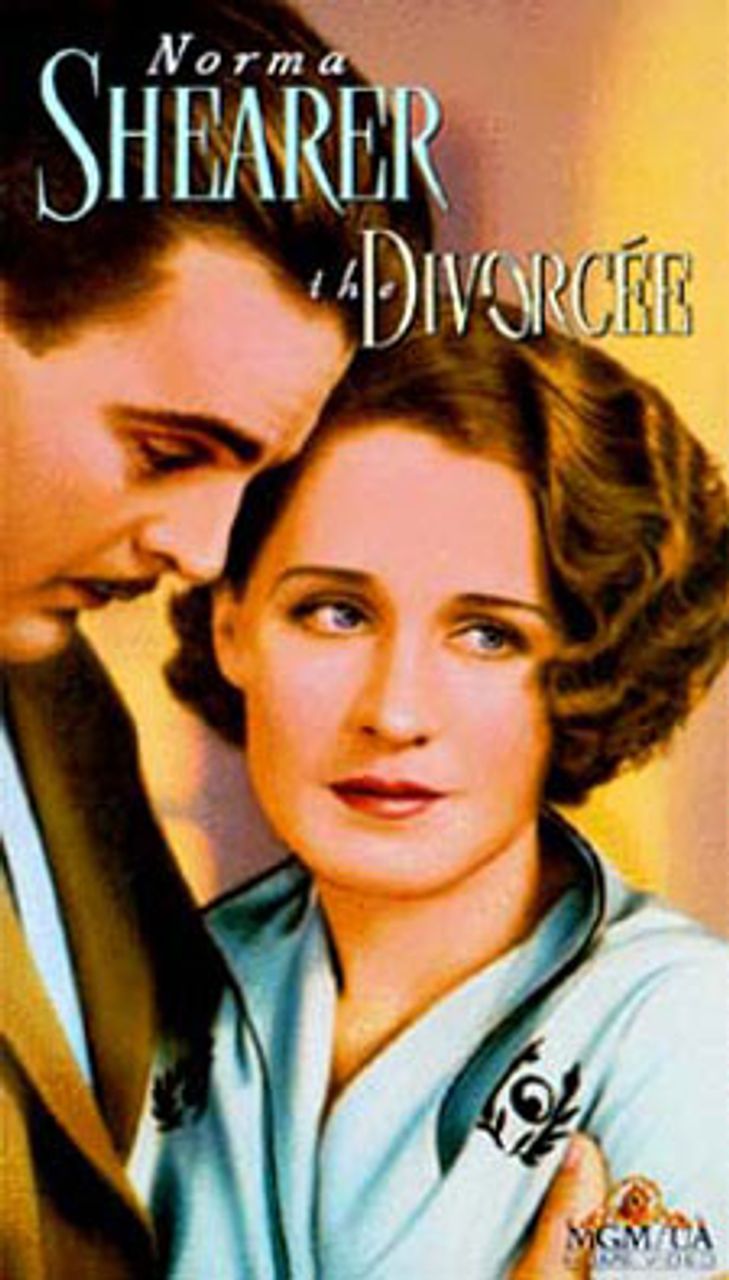

Shearer received an Oscar in 1930 for her performance in The Divorcee (directed by an originally uncredited Robert Z. Leonard). Jerry Martin (Shearer), a member of an upper-class set who spend most of their time partying, marries Ted (Chester Morris), then divorces him, and leads the life of a young businesswoman until a chance encounter makes her realize the error of her ways.

Shearer received an Oscar in 1930 for her performance in The Divorcee (directed by an originally uncredited Robert Z. Leonard). Jerry Martin (Shearer), a member of an upper-class set who spend most of their time partying, marries Ted (Chester Morris), then divorces him, and leads the life of a young businesswoman until a chance encounter makes her realize the error of her ways.

Shearer is excellent as a woman who is at first a naive, impulsive girl, then a submissive wife, then a cynical libertine, and finally an older but wiser woman. The male characters, however, are one-dimensional for the most part.

By 1930-1931, extraordinary events (including world war, revolution in Russia and devastating slump), which affected mass and artistic consciousness in contradictory ways, represented a real threat to the American ruling elite. This threat helps provide the tension in The Divorcee, a tension resolved in a conventional and unconvincing manner.

Three on a Match

Three on a MatchReleased a year later, director Mervyn LeRoy’s Three on a Match deals with this same tension, and once again, unhappily, employs a stale convention to resolve its drama.

Stock footage of major events between 1919 and 1931—Prohibition, the 19th Amendment (women’s suffrage) and the stock market crash—is used to show the uncertainty and social insecurity that shape the lives of three young women.

Vivian Revere (Ann Dvorak) comes from money, while her two friends, Mary Keaton (Joan Blondell) and Ruth Westcott (Bette Davis), are from the working class. As the 1920s pass, Vivian marries a rich, boring lawyer, Robert (Warren William), but then, responding to the mood of the time, divorces the latter for a gambler, Michael (Lyle Talbot), resulting in financial and personal ruin.

Of the three, Mary is initially the least likely to succeed—i.e., she smokes, drinks, and doesn’t care what people say—but a stay in reform school apparently does her good, and she grows into a blunt but caring human being with a career in show business.

Dvorak and Blondell, two exceptional actresses, fully embrace the possibilities of their textured roles. Davis, on the other hand, is given a limited character with little to say, and in only one scene is she the center of attention, and that primarily due to her scanty attire.

The movie ends up merely offering the conformist lesson that society women shouldn’t listen to the “liberation” message and working class women should take advantage of what official society or the rich offer them, if they want to better themselves.

Female

FemaleDirected by Michael Curtiz (Casablanca, Mildred Pierce and many others), and featuring twice-Oscar-nominated Ruth Chatterton, Female (1933), surprisingly, is the most disappointing of the collection.

Chatterton’s Alison Drake inherits the ownership of an auto factory from her father. Tough and strictly business at the plant, Alison chooses young men from her workforce to lighten her evenings, but ignores them the following morning at work: “I treat men exactly the way they’ve always treated women,” she tells one.

All of this changes when she hires a new engineer, Jim Thome (George Brent), whom she also invites to her home for an evening, but who refuses to be her “gigolo.” When Jim continues to reject her advances, she eventually takes an assistant’s advice to become the gentle and helpless woman a “dominant male” like Jim wants, and wins him over.

Chatterton is credible as a corporate executive, so much so that one could readily believe that Allison had ruthlessly worked her way to the top. But once she becomes submissive, Chatterton’s acting turns artificial, to the point where she seems to be satirizing her character. (Perhaps she and Curtiz were being satirical?)

The commentary following Night Nurse offers insights into the film’s production and pre-Code movie making in general.

These five films were made at the height of the Great Depression, an era of unprecedented economic dislocation, mass unemployment and popular suffering. Of the movies in the collection, only Night Nurse attempts to tackle some of the central problems of the time within the limited framework of women struggling against rigid expectations and mores. Lora and nurse Maloney are confronted on a daily basis with the demands and pressures of their jobs, while the movie’s heroic figure, a bootlegger, is the only male character forceful and resourceful enough to attract Lora’s attention.

The remaining films, which concentrate on society women for the most part, contain interesting moments and sequences, but shy away from the concerns that the Depression inevitably generated. And, in any case, the central lesson of those films, should anyone (middle class female or otherwise) choose to consider the wider issues and even opposition to the status quo, is that rebellion against the existing structures only results in greater suffering and punishment. What sort of message was being sent?

Nonetheless, TCM has performed a considerable service in assembling this historically fascinating collection of pre-Code movies.