Former US Senator George S. McGovern, who died October 21, played a key role during the transitional period in which the Democratic Party moved sharply to the right and abandoned any policies of even limited social reform or wealth redistribution.

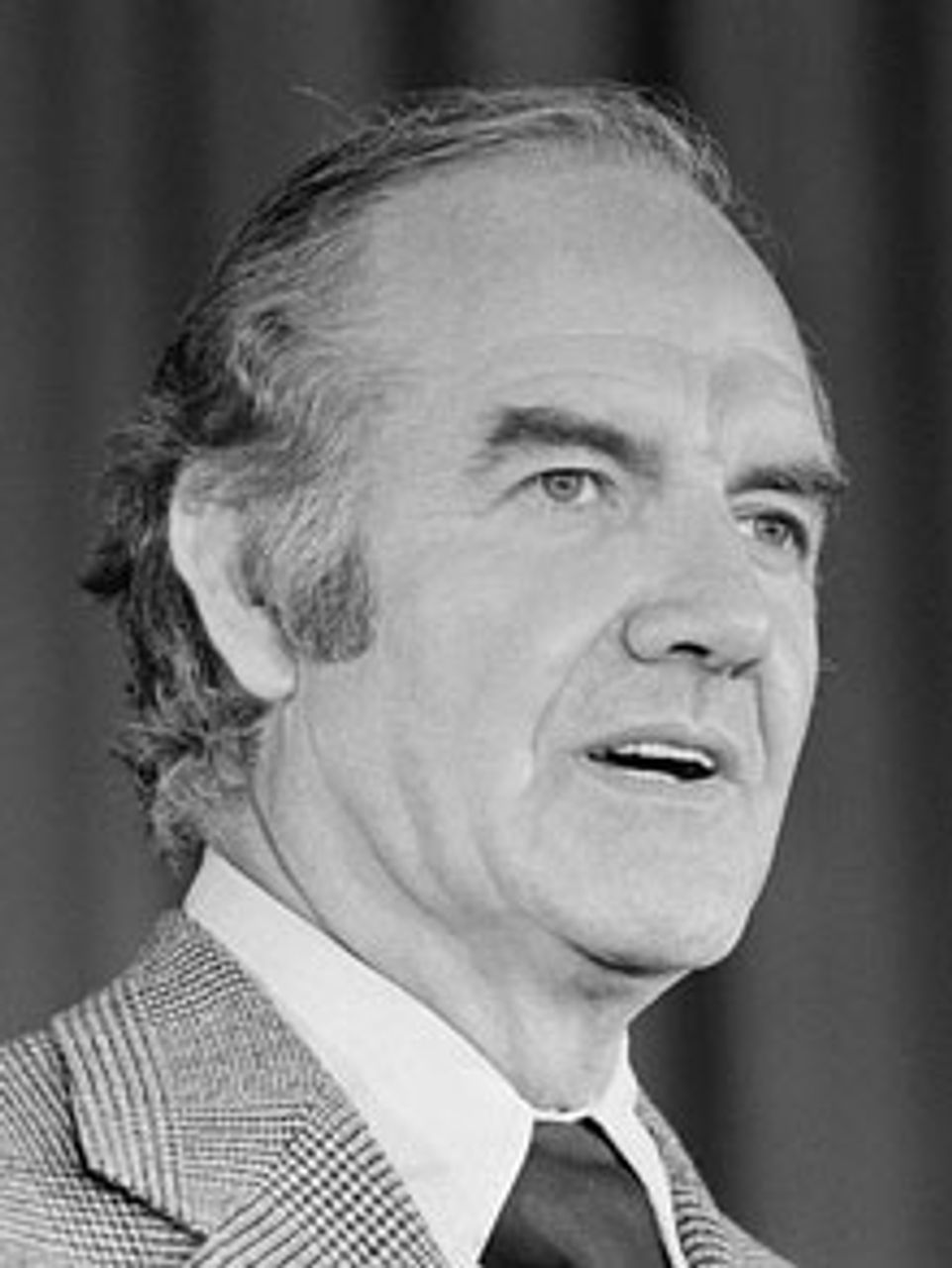

George McGovern in 1972

George McGovern in 1972McGovern won the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972 in a protracted struggle against better-financed opponents who had much more support among party officeholders and Democratic-affiliated institutions such as the AFL-CIO. He went on to a resounding defeat at the hands of Republican incumbent Richard Nixon, losing 49 states and carrying only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.

His role in American politics was greater than such a bald summary might suggest, however. And it embodied sharp contradictions, bound up with the role of the Democratic Party, which serves as the supposedly more “popular” of the two capitalist parties through which the US corporate elite exercises its political monopoly.

McGovern was the last Democratic presidential nominee to openly and unabashedly embrace liberalism as his political standpoint. He was at the same time an instrument of the reorientation of the Democratic Party away from its former working class base of support and a professed concern for economic equality, and towards more privileged layers of the middle class that aspired to rise within capitalist society based on the politics of racial and sexual identity.

Born in 1922 to a traditionally Republican family in small-town South Dakota—his father was a Wesleyan Methodist pastor, from the most conservative branch of that Protestant sect—McGovern experienced the Great Depression as a teenager and enlisted in World War II, serving as a bomber pilot over Nazi-occupied Europe.

These experiences left their mark, and McGovern shifted his educational direction from training for the ministry, where he would have followed in his father’s footsteps, to an eventual doctorate in history at Northwestern University. He wrote his thesis on the Colorado mine wars of 1912-13, when gunmen hired by Rockefeller and federal troops shot down dozens of striking workers.

McGovern was an early supporter of the 1948 Progressive Party campaign of Henry Wallace, the vice president in Roosevelt’s third term, but was repelled by its Stalinist-dominated milieu and ended by voting for Democratic President Harry Truman. By 1952, he had become an enthusiastic campaigner for the Democrats, backing presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson and then throwing himself into efforts to revive the moribund Democratic Party in South Dakota. Four years later he was the Democratic candidate for a South Dakota seat in the House of Representatives, defeating a Republican incumbent.

McGovern lost a Senate race in 1960 against longtime incumbent Karl Mundt, a McCarthyite red-baiter. He was named by incoming Democratic President John F. Kennedy to head what became the Food for Peace program, then returned to South Dakota to win a narrow victory in a Senate race in 1962.

The new senator was one of the first to question the wisdom of the increasing US intervention in Vietnam, although he never challenged the right of American imperialism to use military force and political subversion in its worldwide efforts to suppress the anti-colonial revolution and block the growing influence of the Stalinist regimes in the USSR and China. He voted for every military appropriation sought by the Democratic administrations of Kennedy and Johnson.

McGovern declined appeals to challenge Lyndon Johnson for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968, concentrating instead on his own reelection campaign in South Dakota, until after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in June. Soon after, McGovern agreed to have his name placed in nomination at the Democratic convention, backed by some Kennedy delegates, although it was a token effort. McGovern backed the pro-war nominee, Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

As the anti-war movement radicalized millions of American youth and increasingly turned the majority of the population against the war, McGovern adopted a more outspoken stance, albeit always within the framework of the capitalist two-party system and the defense of American imperialism.

He was capable of giving vent to genuine outrage against the impact of the war, particularly on American soldiers. In a Senate debate in September 1970 over the amendment he jointly introduced with Republican Mark Hatfield to cut off funding for the war, McGovern spoke in terms that would be unthinkable today in bourgeois politics. His remarks are worth quoting, if only to show how far to the right the entire spectrum of the two-party system has moved in the past 40 years. He told the Senate:

“Every senator in this chamber is partly responsible for sending 50,000 young Americans to an early grave. This chamber reeks of blood. Every senator here is partly responsible for that human wreckage at Walter Reed and Bethesda Naval and all across our land—young men without legs, or arms, or genitals, or faces or hopes. There are not very many of these blasted and broken boys who think this war is a glorious adventure. Do not talk to them about bugging out, or national honor or courage. It does not take any courage at all for a congressman, or a senator, or a president to wrap himself in the flag and say we are staying in Vietnam, because it is not our blood that is being shed. But we are responsible for those young men and their lives and their hopes. And if we do not end this damnable war those young men will some day curse us for our pitiful willingness to let the executive carry the burden that the Constitution places on us.”

In the unlikely event that a member of the US Senate or House of Representatives spoke in such terms today, he or she would likely be expelled from the body, vilified in the media, and driven out of official politics overnight—if not subjected to arrest or political violence.

By the time of the 1972 election, the ruling elite was itself deeply split over Vietnam. At the same time, McGovern’s campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination was vital to the preservation of the corporate-controlled two-party system under conditions of growing mass hostility to the war. It served as a safety valve to block any mass political movement emerging to the left of the Democratic Party.

While McGovern publicly opposed the continuation of the war, and occasionally spoke in quite passionate terms, his campaign was otherwise conventional and even, by the standards of American bourgeois politics of the time, quite moderate.

The South Dakota senator was the first Democratic nominee from an agricultural region since William Jennings Bryan, two generations before. McGovern came from an anti-union right-to-work state and had no connections to urban workers or the labor movement, under conditions where the trade unions still represented the bulk of the industrial working class.

Under the leadership of the right-wing, anti-communist bureaucracy, the AFL-CIO had backed Senator Henry Jackson, a diehard defender of the Vietnam War, or former Vice President Humphrey for the Democratic presidential nomination. At the same time, there was growing support in the working class for a break with the Democrats and the building of a labor party based on the unions, under conditions of militant strikes against Nixon’s wage controls, speedup and attempts by the corporations to reverse the gains of previous decades of struggle.

In response to the nomination of McGovern, the AFL-CIO declined to endorse him against Nixon. Far from moving toward the formation of a labor party, large sections of the trade union bureaucracy tacitly supported the Republican candidate who had imposed wage controls in August 1971.

The McGovern campaign and the Democratic Party as a whole were plunged into crisis after the convention that nominated McGovern. His running mate, Senator Thomas Eagleton of Missouri, was subsequently forced to step down after it was revealed that he had undergone electroshock treatment for depression.

McGovern initially defended Eagleton, then forced him to quit, before choosing former Peace Corps director Sargent Shriver as the replacement. By then, the McGovern campaign’s electoral fortunes were in shambles.

McGovern’s victory in the struggle for the party nomination had a more lasting significance, however. In 1968, after the deeply divided convention in Chicago, the Democrats established a commission under his leadership to revise the nomination process.

In the name of making the party more democratic, the commission established racial and gender quotas for delegates and required most delegates to be selected through primary elections, which until then had been rare (Humphrey won the nomination in 1968 without winning a single primary).

This turn by the Democratic Party towards identity politics was a shift away from its previous cultivation of a mass base among workers as well as middle-class layers to a more definitively middle-class orientation. While always a capitalist party, the Democrats had nonetheless cultivated a base in the working class areas of major cities, as well as close ties with the trade unions, which represented nearly 40 percent of the working class in the 1950s, and even into the 1970s still comprised the vast majority of workers in industries like auto, steel, trucking, meatpacking, construction and mining.

In promoting gender and racial identity, the Democrats were orienting to an emerging black elite, to women in business and the professions, etc., not to the masses of black workers whose conditions remained dismal.

The right-wing implications of this shift were demonstrated not so much in McGovern’s own evolution as in the role of those who first came to political prominence in his campaign.

His campaign manager, Gary Hart, became a US senator and presidential candidate in 1984, opposing the more traditional liberalism of Walter Mondale. His Texas campaign organizer, Bill Clinton, then 26, went on to co-found the right-wing New Democratic Coalition and win the presidency on the basis of a repudiation of the New Deal policies of social reform and limited wealth redistribution with which the Democratic Party was once associated.

In the final analysis, this process demonstrates the class role of both bourgeois parties in the United States, which work together to deprive working people of any independent political role. The two parties have a well-developed division of labor, in which the Democratic Party is used to capture and dissipate any popular challenge from below, while the Republican Party sets the agenda and drives the official political system further and further to the right.

McGovern himself followed in the wake of these political shifts, long after he had ceased to have any significant personal role. He was an early supporter of Hillary Clinton in 2008, before switching his support to Barack Obama.