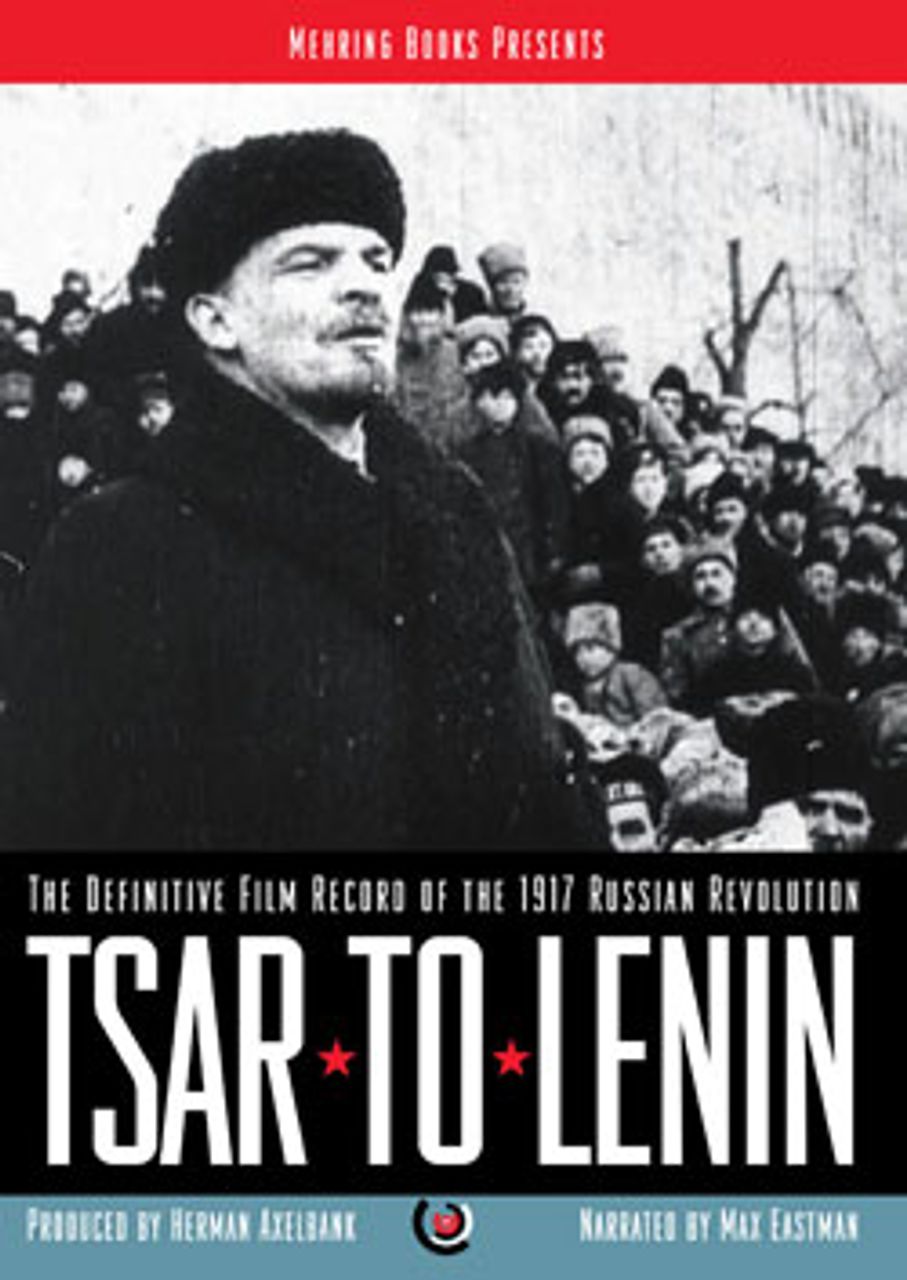

A WSWS reader has written in with a comment on the unique documentary film Tsar to Lenin, available from Mehring Books.

It has generally been conceded by film historians that All Quiet on the Western Front, released in 1930, is the first great talkie, and one of the great films of its era. Lewis Milestone directs the cinematic adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s classic anti-war novel and it still deserves to be seen as a compelling movie and as an early peak in American cinematic art. Its long-standing reputation as the greatest early-American talkie film now needs to be put in serious question with the re-release of Herman Axelbank’s Tsar to Lenin.

It has generally been conceded by film historians that All Quiet on the Western Front, released in 1930, is the first great talkie, and one of the great films of its era. Lewis Milestone directs the cinematic adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s classic anti-war novel and it still deserves to be seen as a compelling movie and as an early peak in American cinematic art. Its long-standing reputation as the greatest early-American talkie film now needs to be put in serious question with the re-release of Herman Axelbank’s Tsar to Lenin.

Most critics prefer not to compare documentaries to conventional movies, but in this case it is necessary, due to the similarity of the material covered, as well as the epoch of the films themselves. Tsar to Lenin was completed in January 1931, which makes it a contemporary of the Milestone classic.

Talking films were in their infancy at the time, and most of the output from Hollywood was so poor in quality, that by today’s standards many of the films of that time are now unwatchable. Many have been lost forever.

Tsar to Lenin wasn’t released until 1937, and then only for a handful of showings in New York City, before it was blackballed by the Stalinist Communist Party. Most people never knew the film existed.

The SEP and Mehring books have righted that injustice with their DVD release of Tsar to Lenin, and it is quite simply a triumph for art and humanity. This film far supersedes any film of its time in content and emotional impact.

The sequences, as the film’s introduction explains, were gathered from over 100 cameras over the course of 13 years, from a broad range of perspectives, including the Tsar’s royal photographers, Soviet photographers, the military staff photographers of Germany, Great Britain, Japan and the United States, and other adventurers. The film’s footage is completely authentic, and it has been put together in chronological order to provide as complete a picture as possible of the Russian Revolution and its civil war aftermath.

This is truly the most complete and authentic film document of its kind.

Herman Axelbank’s footage is the star of the film, but Max Eastman’s narration is the film’s co-star. Today more than ever, these events need explanation. Eastman provides it beautifully and without it, we would have a collection of film clips that would make little sense to most people. Eastman’s descriptions reduce each scene to its clear, understandable essence, while occasionally allowing his ironic wit to come through, thus adding subtle tones to his narrative. It is instructive to quote him to gain a better sense of the film’s impact.

The film begins with portraits of Russia under Tsarist autocracy—great leisure for the Tsar and the landowners, while the masses toil in ignorance and extreme poverty. One portrait of tsarist leisure has him and his entourage aimlessly throwing many balls around on the lawn. Eastman comments dryly, “A Russian [tsarist] conception of the World Series.”

Watch the footage at around 14:00, with the Tsar at the military front. The whole time, he is highly agitated and unable to focus on anything. He is completely unsure of himself and almost child-like in his silly, self-conscious manner. Every moment of his public life is one grand charade.

Here is Eastman’s description of Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich Romanov: “He was 7 feet tall, handsome and imposing! He would have been the Tsar if this were a fairy story.” After a cut to Tsar Nicholas II standing idly in a field, Eastman adds, “Real Tsars are not so imposing.”

The following is Eastman’s commentary about the state of the Russian armies two years into World War I: “The soldiers were being herded into battle; hungry, ill-clad, without ammunition, even without guns. Corruption, treachery, neglect, [and] profiteering had ruined the Tsar’s military organization. Two-and-a-half million dead. Five million wounded. They were lying, like piles of rubbish outside the hospitals; too crowded to contain them; wounded and dying with no clothes on their backs. Two-and-a-half million dead, with no time to bury them.”

Eastman’s descriptions of the February and October 1917 Revolutions are delightful in their concision.

“The funeral for the martyrs of the February Revolution was not a funeral, but a gigantic, triumphal march of the people.”

Then later, “Everybody who has an ideal; inscribes it on a banner, hires a brass band, and demands that it be realized by the new government being born in the Tauride Palace.”

And after the abdication of the Tsar in February 1917, “There was no government. Joy was the sovereign over all of Russia!”

Perhaps the film’s most unforgettable set of images comes from the Civil War, when Admiral Kolchak’s troops execute Soviet prisoners-of-war in the field. A Red soldier laughs as he awaits the firing squad. The prisoners are shot in groups of three, and we see it five different times before his turn comes. “The Red soldier is still laughing!” Eastman narrates in defiance, just seconds before bullets rip through the Red soldier’s flesh, sending him into pit of fresh corpses.

Those were not Hollywood stuntmen, pretending to die, as they were in Milestone’s film.

Axelbank’s footage reveals much about Alexander Kerensky, a leading figure in the Provisional Government following the first Russian Revolution in 1917. He is first shown surrounded by bourgeois supporters in Petrograd. They are thrusting him forward, while he tries to shrink back. He is obviously a feeble and terrified man, who doesn’t rise to the top through brains and force of will, but instead is thrust forward by others who prefer to remain behind the scenes.

The footage of Lenin is striking. He, like Trotsky, spoke to huge crowds without aid of a microphone. He was not a tall man, and Eastman comments on a conversation we see him having in 1920 in Moscow with Parley P. Christensen, the Farmer-Labor candidate for US president. Eastman notes of Christensen, “He towers over Lenin ... physically.”

The film’s final scene is about a minute of Lenin speaking, which we can not hear. Eastman is eloquently narrating the life’s purpose of this brilliant revolutionary leader, who entirely dedicated himself to the cause of freeing humanity from the chains of inequality, with “no trace of personal greed.” Lenin’s eyes shine as he is speaking with the whole of his being and intellect.

Trotsky is no less important. His slogans and Lenin’s were the same: “Kerensky is a tool of the landlords and capitalists,” “Stop the War!” “Confiscate the Land!” “Russia Belongs to the Workers and Peasants!” “All Power to the Soviets!” and he delivered them with the same intensity.

Lenin and Trotsky were the central leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution which ousted the capitalists and established the first workers’ government in history. It was the beginning of the end of the world war, and the beginning of a bitter civil war in which 14 hostile armies surrounded and attacked the Soviet government, in an attempt by the world’s imperialist governments to strangle the revolution.

A major factor in the Red Army’s success in defending the revolution was Trotsky’s brilliance in military organization. A Russian army that had been shattered by Germany in the World War, now had to be rebuilt in the furnace of a life-or-death struggle for survival. “Show me one man who could organize a model army within a year. We have such a man!” Those were Lenin’s words, and he was referring to Trotsky.

The last, best chance for imperialism to kill the revolution is depicted in the scenes showing General Yudenich, backed by materiel from Great Britain, leading the flower of the Tsar’s army, with one officer for every eight men, on a march from Estonia to St. Petersburg. This effort was defeated by the Red Army, led by Trotsky.

As mentioned above, there are dozens of other lesser characters shown in the footage that provide insight into reality, and give Eastman plenty of opportunities to apply his dry sense of humor. The best of Eastman, who later turned away from Marxism, is present in Tsar to Lenin.

Over Axelbank’s images, Eastman comments on Bolshevik leader Kamenev “expounding, as of yet without extreme conviction, Lenin’s demands for a Second Revolution.” Kamenev, whom Eastman describes as a “mild Bolshevik,” is also shown with Cheidze, Tseritelli, and other opportunist leaders of the Provisional Government. This footage seems to foreshadow the triumvirate Kamenev would later form with Zinoviev and Stalin against Trotsky.

Finally, Eastman describes the conclusion of the civil war and the defeat of the counter-revolution organized by the Great Powers:

“On November 14-15, 1920, 135,000 troops on 126 ships leave the Crimea. The world is defeated and all of Russia is now a Soviet Republic!” Shortly after this comment, at precisely 59:21 into a movie that runs just over 63 minutes, Joseph Stalin first appears. Evidently there is no earlier footage of Stalin’s activities as a Bolshevik, which leads one to conclude that nothing he ever said or did was thought worthy of filming by anyone connected with the Russian Revolution.

One feels a certain sadness looking into the faces of the masses that Lenin speaks to in the film’s conclusion. They are among the millions to whom he patiently explained socialism, and who came to believe him. Fifteen years later Stalin would organize the Moscow Trials and exterminate those who had led the revolution. Thirty million Soviet citizens would die in the second imperialist world war.

This is a great reminder to all revolutionists of the terrible cost of not completing such an important task. It is the duty of every socialist to understand this film from the point of view of finishing a task Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolsheviks set out for mankind a century ago.

RS