This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

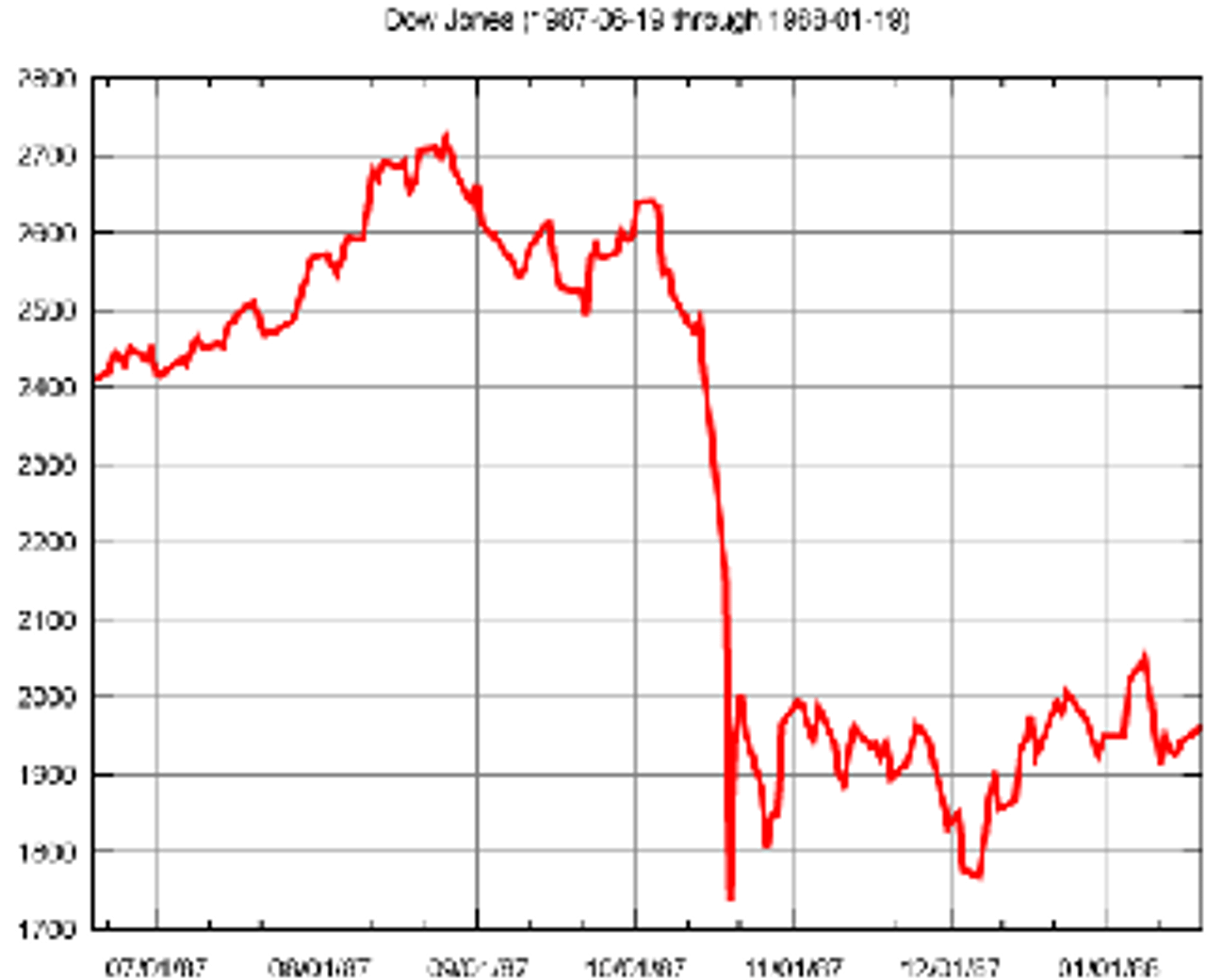

25 years ago: Global stock market crash triggers record losses on “Black Monday”

October 19, 1987 marked the biggest-ever one-day loss of stock values in the history of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Over $500 billion in paper value—22.6 percent of the market’s total value—was wiped out in a single day on the New York Stock Exchange.

October 19, 1987 marked the biggest-ever one-day loss of stock values in the history of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Over $500 billion in paper value—22.6 percent of the market’s total value—was wiped out in a single day on the New York Stock Exchange.

The global crash began when the Hong Kong stock exchange opened for business on Monday and traders began a massive sell-off of stocks in response to the previous week’s 9.5 percent loss on the Dow Jones and US Treasury Secretary James Baker’s public expression of concern on market values. The panic spread westward from the Asian to the European and finally to the US markets. Only four hours after the New York exchange closed on Monday, the Asian markets opened to continued losses. The Hong Kong market was forced to close down for a week.

John Phelan, chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, called the crash “the nearest thing to a nuclear meltdown I ever want to see.” The global bull market which had hit its peak in August, transformed by the end of October to a rout, leaving the global stock exchanges at only 40 to 77 percent of their previous values.

At the center of the global crisis was the US economy. The fall in the value of the dollar was encouraged by the Reagan administration to counteract the growing US balance of trade deficit. Newly appointed Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan began implementing tight money policies, causing uncertainty among foreign investors. The US government’s budget deficit was the highest in history.

The inflated bubble of paper values on Wall Street that sent the Dow Jones average soaring toward the 3,000 mark was punctured as Wall Street was suddenly brought face-to-face with the global decline of American capitalism. The 1987 crash gave the lie to the myth that a market collapse on the scale of the 1929 crash, which led to the Great Depression, could never happen again.

50 years ago: China overwhelms Indian army

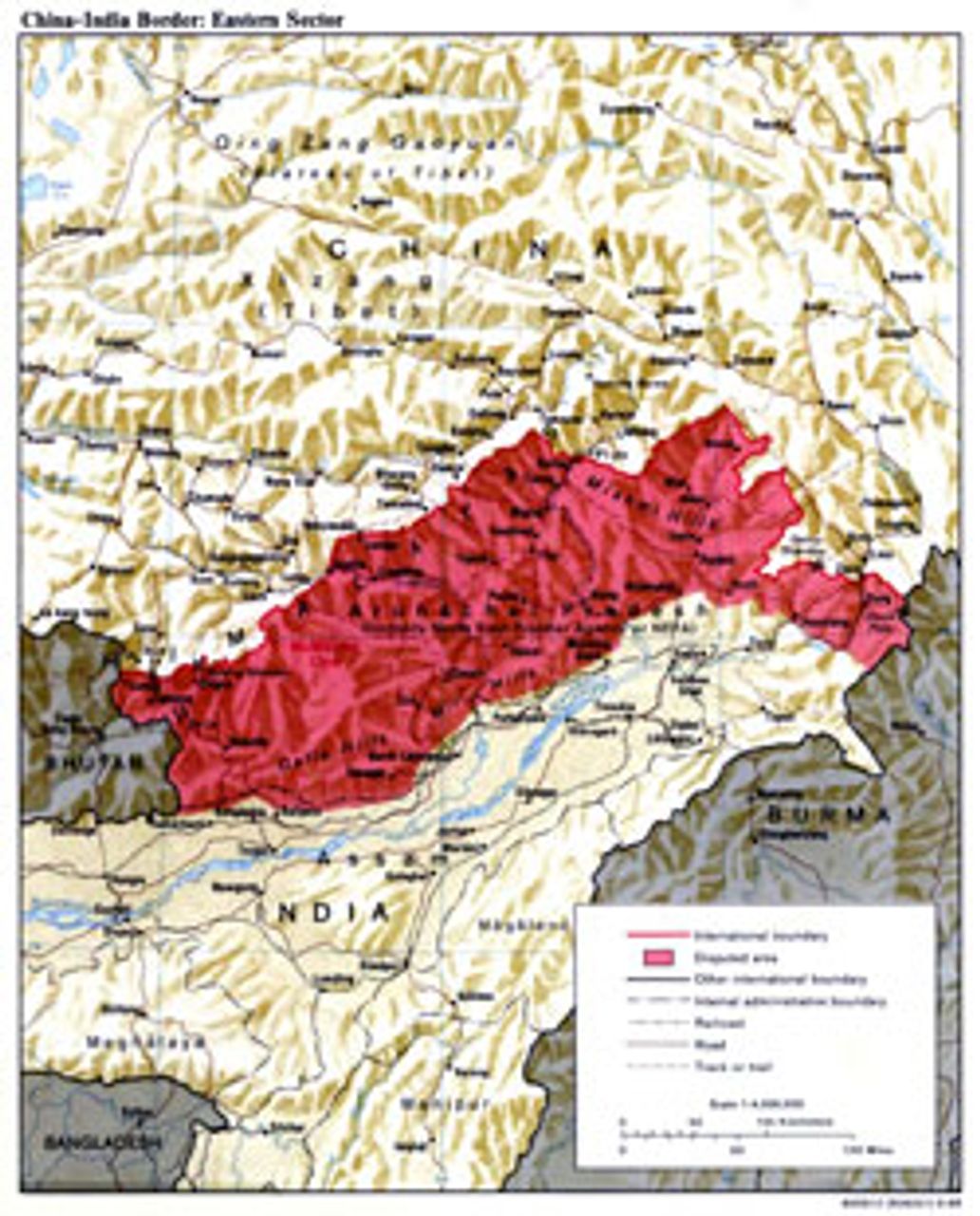

Disputed area between India and China (in red)

Disputed area between India and China (in red)On October 20, 1962, a force of about 30,000 Chinese soldiers launched a two-pronged attack against Indian positions separated by 1,000 kilometers along the disputed Himalayan border between the two countries. The attack came after weeks of skirmishes and days after Nehru publicly ordered the Indian military to expel the Chinese from the areas south of the McMahon Line, drawn up by the British in 1914 when they controlled India and dominated Tibet.

By October 21 India had lost all of its forward posts, and days later Chinese forces had gained control over the bridges spanning the Namkha Chu River. Within one week the Chinese military, hindered largely by the mountainous terrain rather than Indian opposition, had advanced to positions near undisputed Indian territory. The Indian army, it quickly became clear, was unprepared and under-equipped for the conflict.

The fighting also revealed the extent of the Sino-Soviet rift. Among the Stalinist states, only Albania and North Korea offered unqualified support to the Chinese position, while the majority remained silent. Yugoslavia openly supported India, and the Soviet Union supplied it militarily—as did the US. The Indian Communist Party (CPI) supported the Nehru government’s position, with the exception of a Bengal faction that supported the Chinese.

In determining to launch an attack it is likely that the Chinese leadership under Mao Zedong were aware of the developing Cuban Missile Crisis, which in the next days was to bring the US and the Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war.

75 years ago: Gijon and Asturias fall to Franco

Children being evacuated in 1937

Children being evacuated in 1937On October 21, 1937 the last bastion of Republican Spain in the country’s north fell to the advancing columns of General Franco. The Atlantic port city of Gijon was surrendered by the Republican leadership with the Falangist forces led by General Davila still some fifteen miles short of the city’s center. Once again the Republican leadership capitulated without a fight and saved its functionaries while abandoning the soldiers, workers and masses of the region to fascist barbarism. The police and other bourgeois forces within Gijon immediately went over to Franco once the workers militia had left the city.

The Associated Press carried reports as early as October 16 that the Governor of Asturias had fled the city for France with written authority from the central government. On October 20, the remaining Republican leadership absconded by air and sea, leaving the Gijon population to flee to the surrounding hills and the remaining Republican troops,140,000 men and women, to their fate. Most of the remaining Republican forces, some like the Asturian miners, battle-hardened fighters and expert dynamiters, retreated to a mining area between Oviedo and Pajares.

“Why was Gijon not defended?” demanded Felix Morrow in his book Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Spain. Like Bilbao and Santander before it, Gijon was prematurely surrendered and evacuated. Pointing to the advantages afforded by urban environments, Morrow writes, “Again we must repeat: a city of buildings is a natural fortress which must be razed before taken.” A well planned and executed defense of Gijon, supplied by sea, could have tied up 50,000 of Franco’s troops and prevented them unleashing their terror elsewhere.

When the north fell to the Falangist forces, the Republican side lost not only these crucial centers of worker resistance and their industrial production facilities, but also coal supplies from the mines of Asturias. Such was the craven character of the Gijon capitulation that industrial production facilities, including a small arms factory, were not destroyed prior to evacuation.

100 years ago: Italy and Turkey sign Lausanne Treaty

Signing of the Treaty of Lausanne

Signing of the Treaty of LausanneOn October 18, 1912, the Treaty of Lausanne was concluded between Italy and Turkey in Switzerland, ending the Italo-Turkish war. The treaty accorded “independence” under Italian sovereignty to the three Ottoman provinces of Tripoli, Fezzan and Cyrenaica, which now comprise the state of Libya. Turkish troops were recalled from North Africa and the Italian fleet from the Aegean.

Italy paid the equivalent of 4 percent of the Ottoman national debt in return for Turkey’s cession of Libya. Concessions to Turkey included that the Ottoman Sultan continue as the Caliph of Libyan Muslims. Italy retained control of the Dodecanese Islands, which it had seized during the war, and Turkey eventually relinquished all claims in 1923.

The Italo-Turkish war encouraged the growth of nationalism in the Balkans. Having seen how easily Turkey had been defeated by Italy, members of the Balkan League—Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria and Montenegro—prepared to attack the Ottoman Empire. Montenegro had declared war on October 8, 1912, and its allies did the same a week later.

Facing the loss of its territories in the Balkans, Turkey was forced to conclude the unfavourable peace with Italy at Lausanne in order to prepare for military conflict in the Balkans. The Ottoman Empire would lose control of Albania, Salonika, Kosovo and Macedonia—areas that it had held since the 1400s.

Lenin’s view of the predatory colonial character of the Lausanne “peace” treaty was confirmed by subsequent events. “Despite the ‘peace’,” he wrote, “the war will actually go on, for the Arab tribes in the heart of Africa, in areas far away from the coast, will refuse to submit. And for a long time to come they will be ‘civilised’ by bayonet, bullet, noose, fire and rape.”