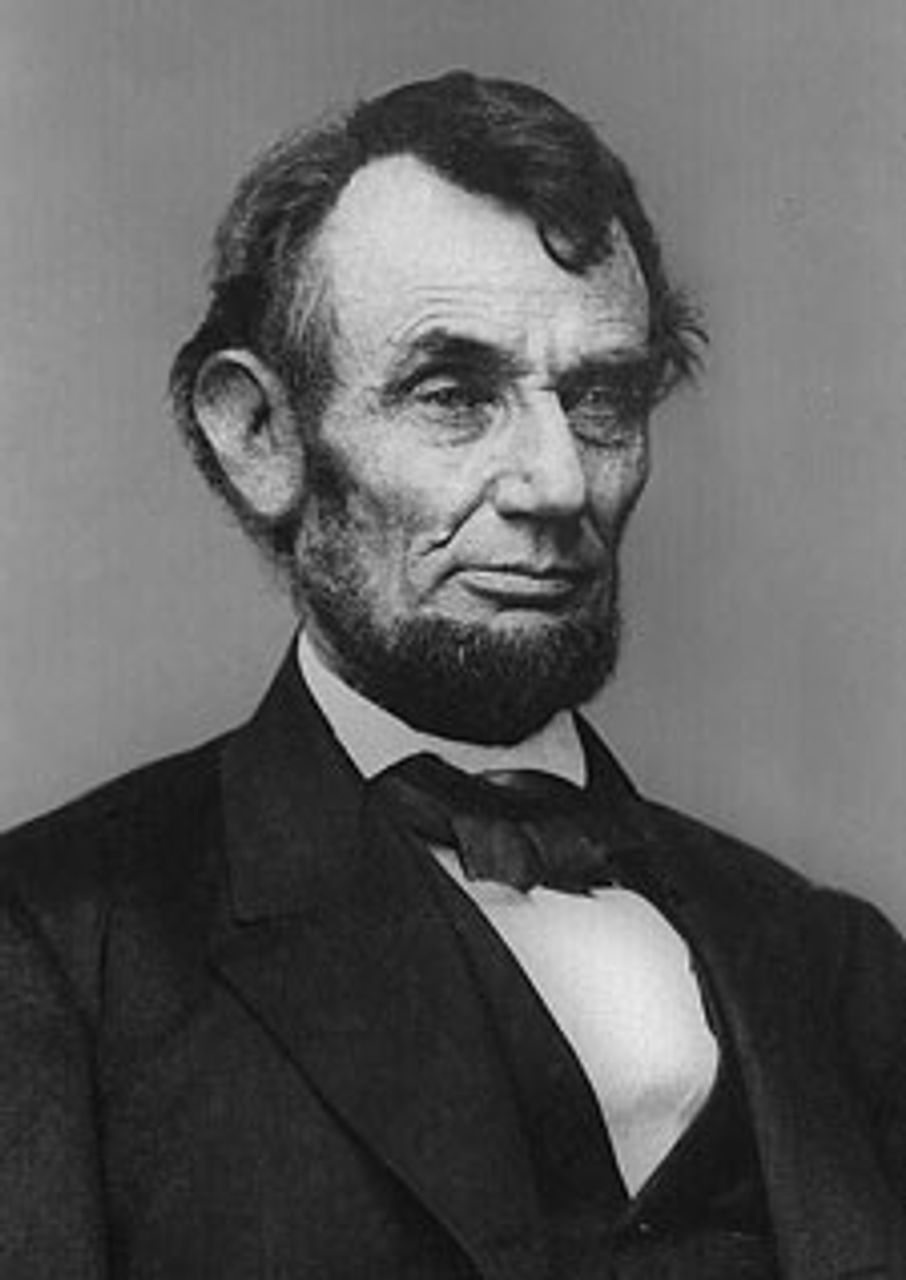

It is among the most remarkable coincidences of history that Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin were born on the same date, February 12, 1809. Lincoln, as the 16th president of the United States, made an immense contribution to the political liberation of mankind. Darwin, in the sphere of science, contributed mightily to its intellectual liberation. Today the World Socialist Web Site pays tribute to the memory of these two very great men.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham LincolnAbraham Lincoln's place in history rests upon his leadership of the US during the Civil War (1861-1865) and his central role in the drafting of the Emancipation Proclamation, which laid the legal basis for the destruction of slavery. But slavery, and the Southern oligarchy that depended upon it, were ultimately destroyed only by the victory of the Union army in the South, which transformed the longstanding sectional conflict into what historian James McPherson has aptly called the second American Revolution.

More has been written about Lincoln than any other figure in US history. Virtually every aspect of his extraordinary political career has been covered in detail. So vast is the legend that surrounds his name that it becomes difficult to abstract the real individual from the icon. But the manner in which Lincoln's life and character became bound up with the greatest historical questions of his time—slavery and the fate of the union—merits particular attention.

Lincoln played a central role in one of the great progressive struggles of modern history. The Civil War arose inexorably out of the fundamental contradictions left unresolved by the first American Revolution, which had proclaimed in stirring language the equality of man, and which had sanctioned the use of revolution to destroy all forms of tyranny.

The revolutionists of 1776, though they were aware of the contradiction between their rhetoric of equality and the existence of slavery, compromised their principles when it came to "the peculiar institution." No doubt many hoped that the problem of slavery would resolve itself in time. But in the aftermath of the revolution the slave-owning class gradually increased its power over the institutions of the state, even as the social weight and industrial might of the North grew.

Territorial expansion in the early Republic persistently raised the problem of the balance of power between slave and free states. The Southern planter class jealously fought to maintain its politically privileged position by seeing to it that new slave territories would at least match in number and voting strength states where slavery was outlawed. Elements among the increasingly deranged Southern elite even entertained visions of a slave empire stretching into the Caribbean.

The provocative US war on Mexico in 1846, which aimed to benefit the "slave power" with vast new territory from Texas to the Pacific Ocean, set into motion a series of events that would ultimately lead to the Civil War. It was in response to this war that Lincoln, then a Congressman from Illinois, gave one of his most noteworthy speeches, condemning it as a false "military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood." Lincoln subjected to scrutiny all of President James K. Polk's pretexts for war, exposing them as false and the war as unconstitutional. In the wake of the Mexican-American War, Lincoln left Congress in disgust, returning to his law practice in Springfield, Illinois.

During the 1850s, the Southern elite consolidated its political domination over the levers of state power, controlling the presidency, the Congress, and the Supreme Court. This power it translated into provocative acts that increasingly incensed Northern opinion.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 was ushered through Congress by Illinois' Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas. The law essentially overturned the Missouri Compromise of 1820, allowing for the expansion of slavery into Northern territory based on "popular sovereignty," and creating a civil war in the Kansas territory between its anti-slavery majority and pro-slavery forces from neighboring Missouri. Then in 1857 came the infamous Dred Scott case, in which the Supreme Court of Chief Justice Roger Taney ruled that people of African descent, slave or free, had no rights as citizens or as people, and that Congress had no authority to outlaw slavery anywhere in the US.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act brought Lincoln back to political life and gave the impetus for the creation of the Republican Party. Lincoln articulated his opposition to the extension of slavery to new territories in his Peoria Speech of 1854. From that point on, his political star rose in tandem with that of the Republican Party and the growing Northern opposition to slavery, which hardened after the Dred Scott decision.

Accepting the Republican nomination for Senate in 1858, Lincoln campaigned against Douglas at a series of legendary debates in Illinois. Thousands of Illinoisans traveled days to attend these hours-long duels. The burning question was slavery. Douglas favored a conciliatory policy toward the South, while Lincoln opposed the further extension of slavery and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The Lincoln-Douglas debates were followed closely throughout the nation, suggesting that history had not only laid hold of Lincoln, but masses of Northerners as well. And though he narrowly lost the election, Lincoln emerged as a figure of national political importance.

What catapulted Lincoln toward national leadership of the Republican Party, however, was his Cooper Union speech delivered in New York City in late February 1860. The speech was a brilliant and carefully measured exposition of the futility of Douglas's advocacy of popular sovereignty. The speech demonstrated not only the force of Lincoln's intellect, but his immense political skills. These talents allowed him to best better-known candidates Senator William Seward of New York and Governor Salmon Chase of Ohio for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860.

Lincoln won a presidential election split in four ways in 1860, beating Democrat Stephen Douglas, whose dreams of compromise were shattered by the withdrawal of the Southern Democrats from his own party behind the nomination of John Breckinridge of Kentucky. The remnants of the Whig Party nominated John Bell. The polarization of the country was such that Lincoln won every Northern state except for New Jersey, but was barred from the ballot in all but two Southern states.

Lincoln's victory was met with the secession of most of the Southern states within three months. Then, in April 1861, Southern forces attacked a federal military base at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. In response, Lincoln immediately called for a popular mobilization to defeat what Lincoln would henceforth refer to as a rebellion. He faced a daunting political task.

Lincoln's unwillingness to compromise over the survival of the union was met by incomprehension and opposition among many in the North, who believed that it would be impossible, or unwise, to defeat the Southern insurrection. Among these were leading members of the military brass, including its top general, George McClellan, whose refusal to prosecute the war with the necessary level of determination approached the level of treachery.

It is well known that Lincoln's initial intention was not the destruction of slavery, which he personally opposed, but the preservation of the union. He famously wrote to abolitionist Horace Greeley in 1862, "If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that." Abolitionists, such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, found this position inadequate and doomed to failure. Ultimately the abolitionists were proven correct.

Lincoln eventually came to recognize that the defeat of the Southern insurrection required that the union adopt revolutionary policies; that the union could not be saved without destroying the Southern oligarchy and the slave system. Once he arrived at this conclusion, the determination with which he pursed this revolutionary objective elevated him to be one of the great political leaders, not only of the US, but of modern history.

Lincoln proved himself to be a politician of extraordinary agility. He demonstrated an ability to size up a situation and its likely course of development, allowing crucial questions to mature before making a decision. At moments, his patience in allowing events to develop appeared to approach the level of temporizing.

Karl Marx, who reported on the American Civil War for a German newspaper, noted this quality as early as 1862, after Lincoln dismissed McClellan, writing "President Lincoln never ventures a step forward before the tide of circumstances and the general call of public opinion forbid further delay. But once ‘Old Abe' realizes that such a turning point has been reached, he surprises friend and foe alike by a sudden operation executed as noiselessly as possible."

It was because of his determined prosecution of the Civil War that the figure of Lincoln became identified with the great historical cause of emancipation. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which proclaimed that "all persons held as slaves" within the Confederacy "are, and henceforward shall be free." The Emancipation Proclamation was necessitated by the military exigencies of the war. But it frankly acknowledged, for the first time, the war's revolutionary character. By legally freeing the slaves—the largest state seizure of private property in world history prior to the Russian Revolution—Lincoln aimed a death blow at the entire social order in the South.

The class conscious workers of Europe viewed Lincoln as the leader of a great progressive cause—the destruction of slavery—to which they fully identified and gave their political solidarity. This was true especially of the English working class, even though the Civil War starved their textile mills of cotton. Though the English capitalists had accrued enormous profits from the American South, the British workers' hatred of slavery made intervention in the war on the side of the South—a distinct consideration until 1864—politically impossible.

Upon his reelection, Marx addressed congratulations to Lincoln on behalf of the First International. It fell to Lincoln, Marx wrote, "the single-minded son of the working class, to lead his country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of an enchained race and the reconstitution of a social world." Marx's letter was graciously received, and replied to, by Lincoln's ambassador to Britain, Charles Francis Adams, the grandson of John Adams.

The strength of integrity that underlay his actions accounts for the extraordinary and simple eloquence with which he articulated the ideals of the union to an international audience. Standing alongside Thomas Jefferson's prose in the Declaration of Independence, Lincoln's speeches have lost none of their vitality; his memorable formulations remain among the most eloquent of the English language.

Lincoln emerged just as American literature was establishing an artistic presence of world note; Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville were his contemporaries. Lincoln's primary literary influences were the King James Bible and Shakespeare, though his interest in the former was entirely literary. He never joined a church, and once declared, "The Bible is not my Book and Christianity is not my religion. I could never give assent to the long complicated statements of Christian dogma." His associates remember that Lincoln could recount by heart long passages from Shakespeare's histories and tragedies.

Biblical metaphor and the Poet's grasp of historical drama suffused Lincoln's prose. In the Gettysburg address of 1863, Lincoln identified the struggle as a war to ensure "that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth." In 1858, in a debate with Douglas, Lincoln said "as I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy." In accepting the Republican nomination for US Senator from Illinois in 1858, Lincoln prophetically warned, "A house divided against itself cannot stand."

In his second inaugural address, Lincoln noted with sardonic incredulity the religious overtones of the Civil War. "Both [sides] read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged."

Lincoln was genuinely humane. To the consternation of his generals, he suspended the death sentences of hundreds of soldiers accused of fleeing battles. In the largest single act of executive clemency in US history, he personally reviewed and commuted the death sentences of 269 Sioux men, Native Americans, who were sentenced to hang for an 1862 uprising in Minnesota.

He was also known as a master storyteller and man of unusual wit and humor. But cohabitating with these characteristics was a profound melancholy, always evident in photographs of the man's visage. During the Civil War, Lincoln would wait in Washington at a telegraph office for word on the results of battles and casualties. The war that lasted four years and claimed the lives of over 600,000 weighed heavily on Lincoln, as did the personal tragedies that beset his family and the turbulence of his wife, Mary Todd. Death took two young children from the couple; Lincoln was especially attached to the second, Willie, who died in 1862 at the age of 11, likely of typhoid.

In poetic tragedy, Lincoln himself was fatally shot on April 14th, 1865, one week after the surrender of the Confederacy at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Lincoln was attending a comedy at Ford's Theater in Washington when John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor, entered his box and shot him in the back of the head.

In the wake of Lincoln's assassination, Marx again took up his pen on behalf of Europe's socialist workers, this time addressing himself to Andrew Johnson, Lincoln's far lesser vice president. Lincoln was a man, Marx wrote, "neither to be browbeaten by adversity, nor intoxicated by success, inflexibly pressing on to his great goal, never compromising it by blind haste, slowly maturing his steps, never retracing them, carried away by no surge of popular favor, disheartened by no slackening of the popular pulse, tempering stern acts by the gleams of a kind heart, illuminating scenes dark with passion by the smile of humor, doing his titanic work as humbly and homely as Heaven-born rulers do little things with the grandiloquence of pomp and state; in one word, one of the rare men who succeed in becoming great, without ceasing to be good. Such, indeed, was the modesty of this great and good man, that the world only discovered him a hero after he had fallen a martyr."

Perhaps it was the combination of his conviction and humanity in prosecuting the great cause of the Civil War that maintains Lincoln's hold on our sentiments. It is hard to think of another figure in modern history whose memory arouses such genuine feeling of profound affection 144 years after his death. Lincoln's assassination in 1865 is still deeply felt as a great historical tragedy.

However, within a generation of his death, official celebrations of Lincoln provided the US ruling class a means of sanitizing the revolutionary significance of his life and papering over new contradictions that the North's victory in the Civil War had brought to the fore. By 1877, the conflict of social classes had erupted in the US, punctuated by massive and bloody strikes throughout the remainder of the 19th century. This new conflict would be the central driving force of US history from that point on.

Not coincidentally, in that same year, 1877, the policy of Reconstruction in the South was abandoned. Northern capitalists, operating through the Republican Party, concluded a pact with the defeated Southern elite, allowing for the latter's political rehabilitation in exchange for the unfettered dominance of industrial capitalism and its policies throughout the land.

Lincoln's assassination leaves forever unanswered how he would have responded to the political crisis that emerged during Reconstruction. Yet the development of the union along capitalist lines was a historically determined process, with all that that entailed. It is difficult to imagine that Lincoln would have been able to prevent the ultimate betrayal of Reconstruction.

Over the course of the ensuing decades, the great mass of the African-American population was deprived of its civil rights and subjected to the humiliations of an apartheid regime enforced by lynching and every manner of cruelty. The systematic denial of civil rights to African Americans would continue into the 1960s—100 years after the Civil War.

But this history in no way detracts from Lincoln's position as the leader of a genuinely progressive and democratic revolution. Like every great historical figure, Lincoln bears the imprint and limitations of his time. But every progressive historical cause, in a certain sense, rises above its own time and speaks to the generations that follow. Lincoln's actions, and the language he used to justify and explain them, continue to inspire.

Tom Eley

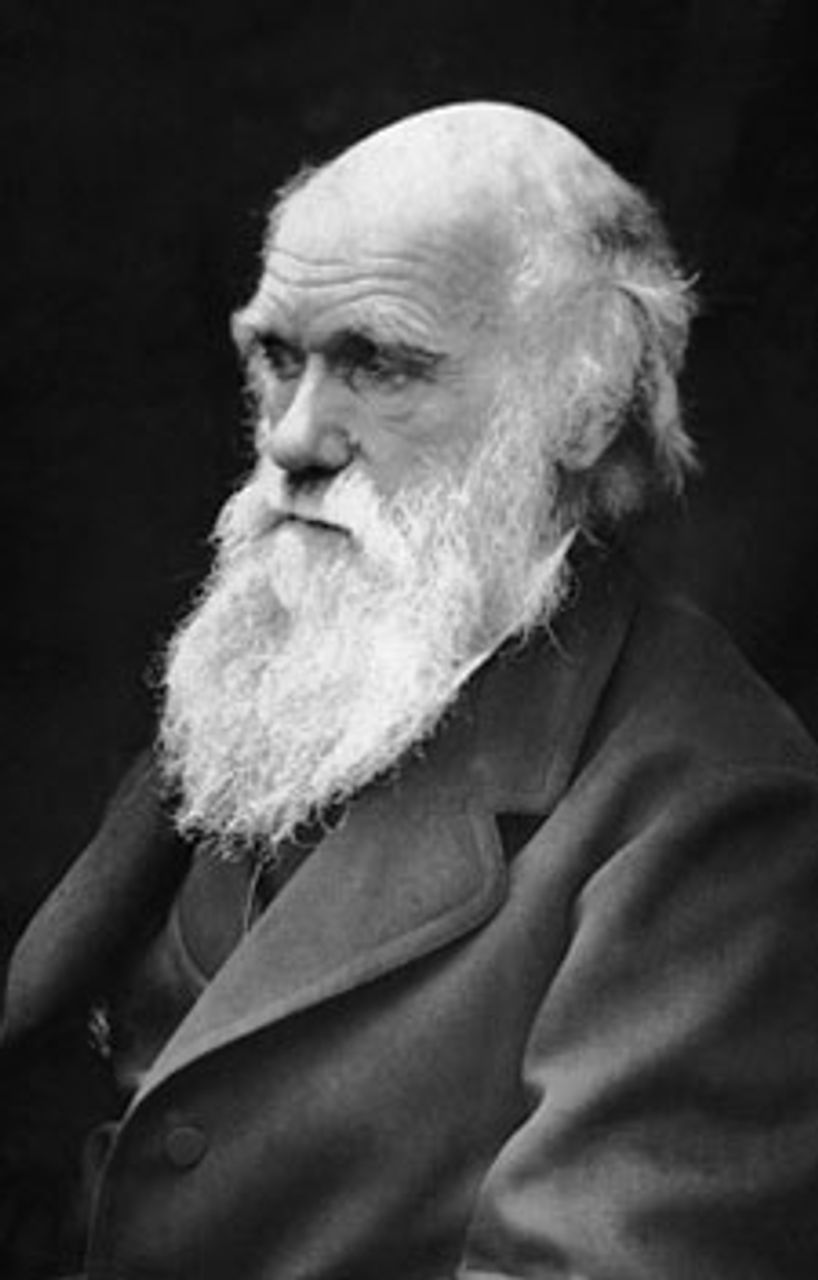

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin

Charles DarwinCharles Darwin's publication of On the Origin of Species heralded a revolution in our understanding of the natural world. Assimilating the scientific accomplishments of the Enlightenment, Darwin discovered the dialectical laws of nature governing the emergence of complex forms in natural history. Two hundred years after his birth, Darwin's Evolution by Natural Selection remains the unifying theory of an ever-expanding array of biological sciences.

The discovery of Evolution by Natural Selection must be understood within the context of the growth of Enlightenment naturalism, of which Darwin's theory is an epic culmination. Advances in optics had allowed Copernicus, Bruno and Galileo to replace theological cosmology with the scientific conception of a universe governed by laws derived through observation, rather than scripture. Similarly, the law of Natural Selection as outlined in Darwin's On the Origin of Species synthesized a vast body of knowledge accumulated through anatomical sciences, experimentation in breeding, taxonomy, geology and scientific expeditions global in scale.

Great collections of organisms discovered through voyages in the 18th and 19th centuries were categorized according to their anatomical distinctions by naturalists such as Carl Linnaeus, Geoffrey St. Hilaire, Georges Cuvier and Robert Owen. Organisms were hierarchically sorted according to their anatomical affinities, which recognizably corresponded to their respective conditions of existence.

Some naturalists, including the Comte de Buffon, Lamarck, Robert Chambers and Darwin's grandfather, Erasmus, had postulated long before Darwin that organisms changed over time. Geologist Charles Lyell, commenting on the bones of extinct organisms buried in the mantle of the earth, recognized that life had altered substantially during the earth's long history, but having no mechanism by which to explain these alterations he suggested their creation by God.

Following his voyage aboard the HMS Beagle in 1836, Darwin came to recognize that living and extinct species "had not been independently created, but had descended, like varieties, from other species." Darwin observed that variation characterized all organisms, and that these variations could be passed on through generations by the principle of heredity. He also saw that in the struggle for existence, certain varieties were apt to survive, while others were not. He famously concluded his 1859 Origin of Species:

"Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is a grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved."

Darwin's discovery immediately produced an uproar, and to this day is at the center of countless intellectual and political controversies. The name of Darwin remains anathema to the religious right and all those who encourage and cultivate, for one or another reactionary purpose, ignorance and superstition. The theory of Evolution by Natural Selection does not merely overturn the Biblical story of creation, a "manifestly false history of the world" according to Darwin, but places the emergence of mankind and thought firmly within the domain of natural history.

"Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws," wrote Darwin, including humanity and the "organs of the mind." He postulated that through an understanding of evolution, "psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation."

Darwin's achievement closely parallels that of Marx and Engels, who were among the first to understand the significance of his work. The writing of Capital and discovery of the historical laws underlying social development equally reflect the culmination of Enlightenment achievement.

Darwin looked with confidence to the future, to young and rising naturalists, and wrote that through an understanding of evolution, "we can dimly foresee that there will be a revolution in natural history." He could not have been more correct. Darwin's theory has since flourished, and become enriched through Mendelian genetics, the Modern Synthesis, the discovery of DNA and a vast array of modern biological disciplines.

His theory is more alive today than ever: No field of biology can be understood without evolution, certainly the unifying theory of life. Evolution is at the heart of biochemistry, genetics and microbiology, developmental biology, epidemiology and modern medicine. Evolution has continued along traditional paths such as paleontology, but also expanded into exciting new realms including neurobiology and biopsychology.

Two hundred years after his birth, the scientific and intellectual revolution inspired by Charles Darwin's work continues to unfold and gather strength.

Daniel Douglass