Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

The following is the third of a four-part series marking the first anniversary of the BP Gulf oil disaster. Part 1 was posted April 20; part 2 was posted April 21.

The release of 200 million gallons of crude oil and millions of gallons of chemical dispersant into the Gulf of Mexico over the space of three months last year makes the BP Gulf oil blowout one of the worst environmental catastrophes in human history.

BP and the Obama administration have from the beginning obscured the dangers posed by the spill to the ecosystem of the Gulf and to human health. This position was reiterated last week by Janet Lubchenco, head of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), who declared that the Gulf is “much better than people feared,” and by Obama “claims czar” Kenneth Feinberg, who predicted the Gulf would be back to normal by 2012.

In fact, the disastrous longer-term consequences of the BP blowout are only now beginning to be registered, in spite of efforts to suppress environmental study by NOAA and the US Justice Department.

The myth of the vanishing oil

The question of the blowout’s environmental and human health impact has centered on the question of what has happened to the spilled oil. The Obama administration, NOAA, BP, and scientists allied with the oil industry have persistently argued that the lack of visible evidence of the oil indicates that the blowout was not so serious as feared, or else that the oil has already been broken down by microbes.

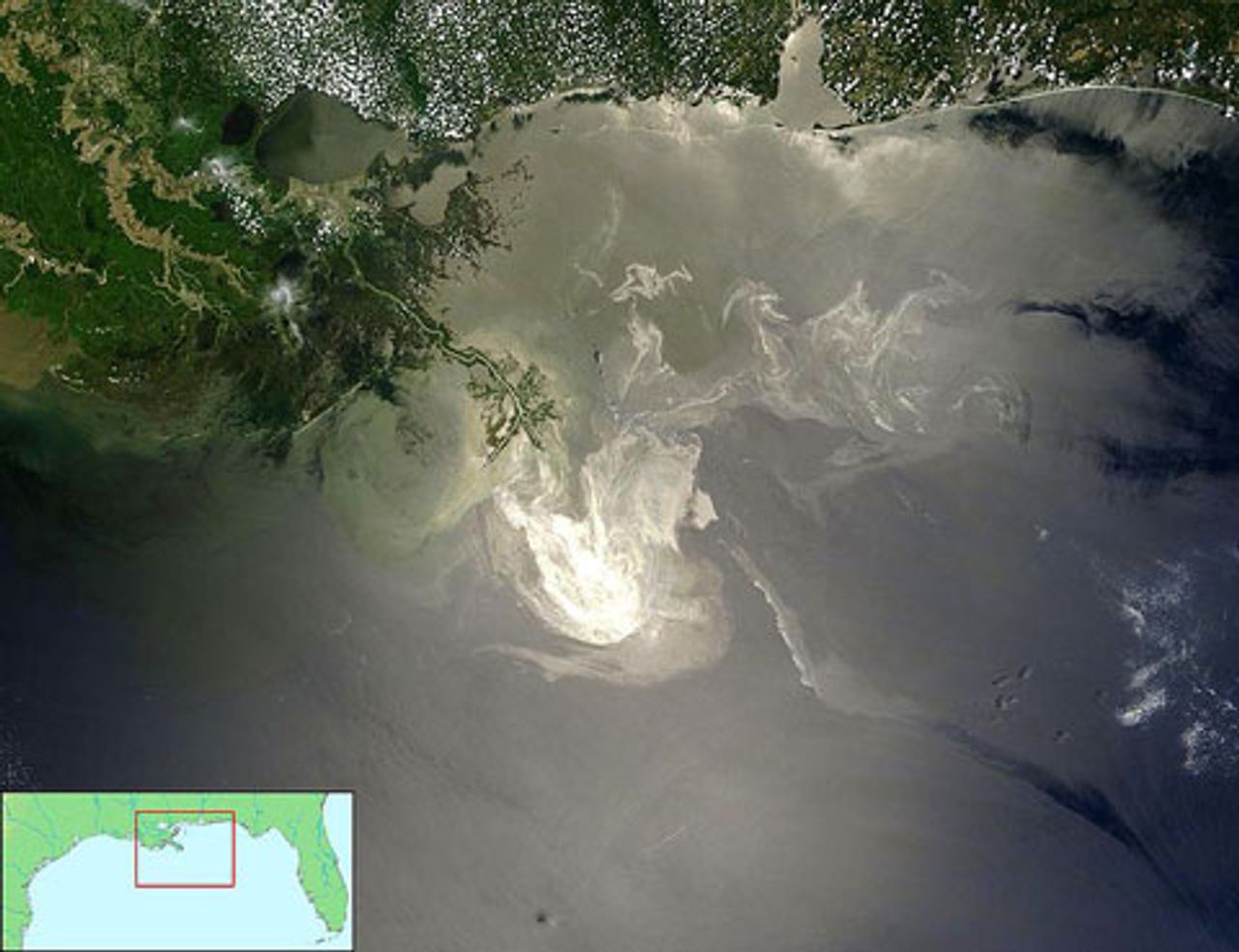

These arguments are disingenuous on a number of counts. There is in fact overwhelming visual evidence of the enormous size of the spill, which at its worst could clearly be seen from satellites in outer space, stretching over hundreds of square miles in the Gulf.

At least 60 miles of Gulf coastline are oiled to this day, and tar balls continue to wash ashore. Louisiana fishing boat captain Kerry O’Neill, who is now working as a subcontractor for the oil cleanup, spoke to the World Socialist Web Site from his boat on Friday. He said that there are still large amounts of oil along parts of the Louisiana coast, including the area he was working that day, and that in some places the shoreline has receded by a staggering 50 feet.

At least 60 miles of Gulf coastline are oiled to this day, and tar balls continue to wash ashore. Louisiana fishing boat captain Kerry O’Neill, who is now working as a subcontractor for the oil cleanup, spoke to the World Socialist Web Site from his boat on Friday. He said that there are still large amounts of oil along parts of the Louisiana coast, including the area he was working that day, and that in some places the shoreline has receded by a staggering 50 feet.

Many oyster beds have been lost. Fishing levels for the year are reportedly normal, but biologists warn that the population consequences for many species will not register in the first year. Biloxi, Mississippi shrimpers say that they are still hauling up nets full of oil with their shrimp.

Such experiences are common in the Gulf. “You talk to people who live around the Gulf of Mexico, who live on the coast, who have family members who work on oil rigs. It’s not OK down there,” said marine biologist Samantha Joye of the University of Georgia in a recent interview with the Guardian. “The system is not fine. Things are not normal. There are a lot of very strange things going on—the turtles washing up on beaches, dolphins washing up on beaches, the crabs. It is just bizarre. How can that just be random consequence?”

Even to the extent that there has been a lessening of the visual evidence of the spill, this has much to do with the effort by BP and the Obama administration to cover it up, which has included blocking scientists and independent observers from the site of the blowout and destroying the corpses of animals found on beaches over the past year.

A number of scientists, Joye foremost among them, have carried out important work undermining claims that the oil has simply vanished. It was Joye’s team that first discovered massive underwater plumes of oil in the Gulf of Mexico. BP and NOAA first disputed the evidence for this, but the plumes’ existence has since been confirmed. It is likely that these plumes were created by the dumping of large quantities of chemical dispersants into the water column above the Macondo well to break the oil up before it reached the surface—and thus to hide it from public view.

More recently, Joye has documented that large quantities of oil are heaped up on the ocean floor in an area covering fully 2,900 square miles of the Gulf. In this extensive area, her submarine took 250 samples from the sea floor and photographs of oil-coated ocean floor life, “consistently [finding] dead fauna at all these sites,” Joye said.

The Obama administration attempted to silence Joye and other scientists who have exposed BP’s claims that the damage was “very, very modest,” in the words of CEO Tony Hayward. Critical scientists “were bombarded with phone calls from furious officials, from NOAA and other government agencies,” the Guardian reports.

“I felt like I was in third grade and my teacher came up to me with a ruler and smacked my hand and said: ‘You’ve just spoken out of turn.’ They were very upset,” Joye said.

While the claim that the “oil is gone” is simply false, there is more to the question than whether it is physically present or has been broken down. Heavy crude can suffocate the flora and fauna of the sea and the coast, but is not in and of itself the biggest problem.

As oil breaks down, the chemicals contained within it are released into the water or air, including carcinogenic compounds such as benzene. Scientists believe that these toxic chemicals were accentuated, rather than diminished, by chemical dispersants—and were very likely made more easily absorbable into the food chain, where they increase in concentration as they work their way up from simple organisms to the most complex. It is this process, known as bioaccumulation, that may explain the ongoing die-off of large sea animals in the Gulf.

Unusual numbers of marine mammals, endangered sea turtles, sea birds and fish continue to die and wash ashore on the shores of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida. So pronounced are these deaths among dolphins and porpoises that NOAA in February declared “an unusual mortality event.”

The designation is still in place. But rather than allowing independent scientists to analyze the dolphins, NOAA has been disposing of them or taking sick animals out to sea. This makes it impossible to determine the cause of death or illness.

“We are not able to conduct necropsies on these animals any more either,” Moby Solangi, director for the Institute of Marine Mammal Studies in Mississippi, told Reuters. “This is all because of the BP criminal investigation. I know that everyone thinks they are doing their best but we must have answers and help every marine animal we can.”

At least 406 dolphins have washed ashore dead in the past 14 months. In the past few months, upwards of one-third of the deaths have been among newborn or stillborn calves. NOAA has documented that in a handful of these dead animals oil from the Macondo well was found.

The role of the chemical dispersant Corexit in the deaths is not known. To this day, manufacturer Nalco has refused to reveal the contents of the toxic substance, claiming it is a “trade secret.” Both varieties of Corexit used in the Gulf are banned from use on oil spills by the United Kingdom, and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considers Corexit to be of less effectiveness—and higher toxicity—than other dispersants readily available on the market.

The advantage of Nalco to BP appears to be twofold. In the first place, its leading personnel are tightly linked to both BP and ExxonMobil. But as Kieran Suckling of the Center for Biological Diversity pointed out in a Friday interview with the WSWS, the UK’s banning of the use of Corexit meant that BP had a large stock that needed to be used up.

Impact on human health

The human health impact of intense or long-term exposure to both oil and chemical dispersants is known to include a number of serious or even fatal conditions, including cancer, damage to the central nervous system, organ failure, skin lesions, asthma and other respiratory problems.

Last year many workers involved in the cleanup suffered severe health problems. But BP saw to it that these low-wage workers—who in most cases were not given training or even basic safety equipment—were shepherded into a BP-controlled health care system. Made to sign legal waivers, the workers were also barred from speaking to the media.

Nonetheless, a number of health problems have emerged among cleanup workers and Gulf residents that are consistent with the sorts of problems reported by those exposed to toxins from oil and dispersants in earlier spills.

A doctor in Raceland, Louisiana is treating some 60 patients with the same combination of strange conditions. Mike Robichaux, an otolaryngologist, blames exposure to oil and dispersant for symptoms that include severe memory loss, extremely high blood pressure spikes, fluctuating blood sugar levels, and respiratory and gastrointestinal problems.

Robichaux believes that even in Raceland far more people are sick than he is treating, but they do not come forward. Among those with the ailments, “Ninety percent of them are getting worse,” he said.

One of his patients is Jamie Simon, 32, who last year worked on a cleanup barge as a cook. Simon told AFP that she was told the dispersants that were sprayed on her and other workers, which caused immediate skin irritation, were safe.

“I was exposed to those chemicals, which I questioned, and they told me it was just as safe as Dawn dishwashing liquid and there was nothing for me to worry about,” she said. She now experiences dizziness, vomiting, repeated ear infections, a swollen throat, bad vision in one eye, and loss of memory.

BP refuses to admit that any sickness took place as a result of exposure to oil and dispersants. “Illness and injury reports were tracked and documented during the response, and the medical data indicate they did not differ appreciably from what would be expected among a workforce of this size under normal circumstances,” it wrote in a recent media statement, adding that any worker compensation would have to “be supported by acceptable medical evidence.”

A public health study commissioned by the non-profit Louisiana Bucket Brigade of about 1,000 people in four Southeast Louisiana parishes—Jefferson, Terrebonne, St. Bernard and Plaquemines—found that nearly half, 46 percent, of respondents reported being exposed to oil or dispersant, and 72 percent of those exposed reported experiencing at least one symptom that they believe was associated with exposure. The reported symptoms are consistent with those reported elsewhere in the Gulf and among cleanup workers, including nausea, dizziness and skin irritation. Among those with no health insurance, only 23 percent sought medical help for their conditions—another indication that spill-related health problems are likely being underreported.

The population of the Gulf is also suffering psychological consequences from the spill, a study from a team of doctors led by Liesel Ritchie of the University of Colorado’s Natural Hazards Center has found.

The study, which focused on the southern part of Mobile County, Alabama, found that one fifth of respondents are suffering from severe spill-related psychological stress, and another quarter are suffering moderate stress. The stress is related to worries over family health, economic loss, and ties to the ecosystem.

The study’s authors had previously analyzed the mental impact of the 1991 Exxon Valdez oil spill in the town most impacted by it, Cordova.

“Given the social scientific evidence amassed over the years in Prince William Sound, Alaska, we can only conclude that social disruption and psychological stress will characterize residents of Gulf Coast communities for decades to come,” the study’s authors write.

To be continued