US and Pakistani officials held intensive talks yesterday as outrage grew in the Pakistani population and army over the NATO bombing of two Pakistani border posts on Saturday. The raid, mounted in blatant violation of Pakistani sovereignty, killed 24 Pakistani soldiers near Salala on the Pakistan side of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

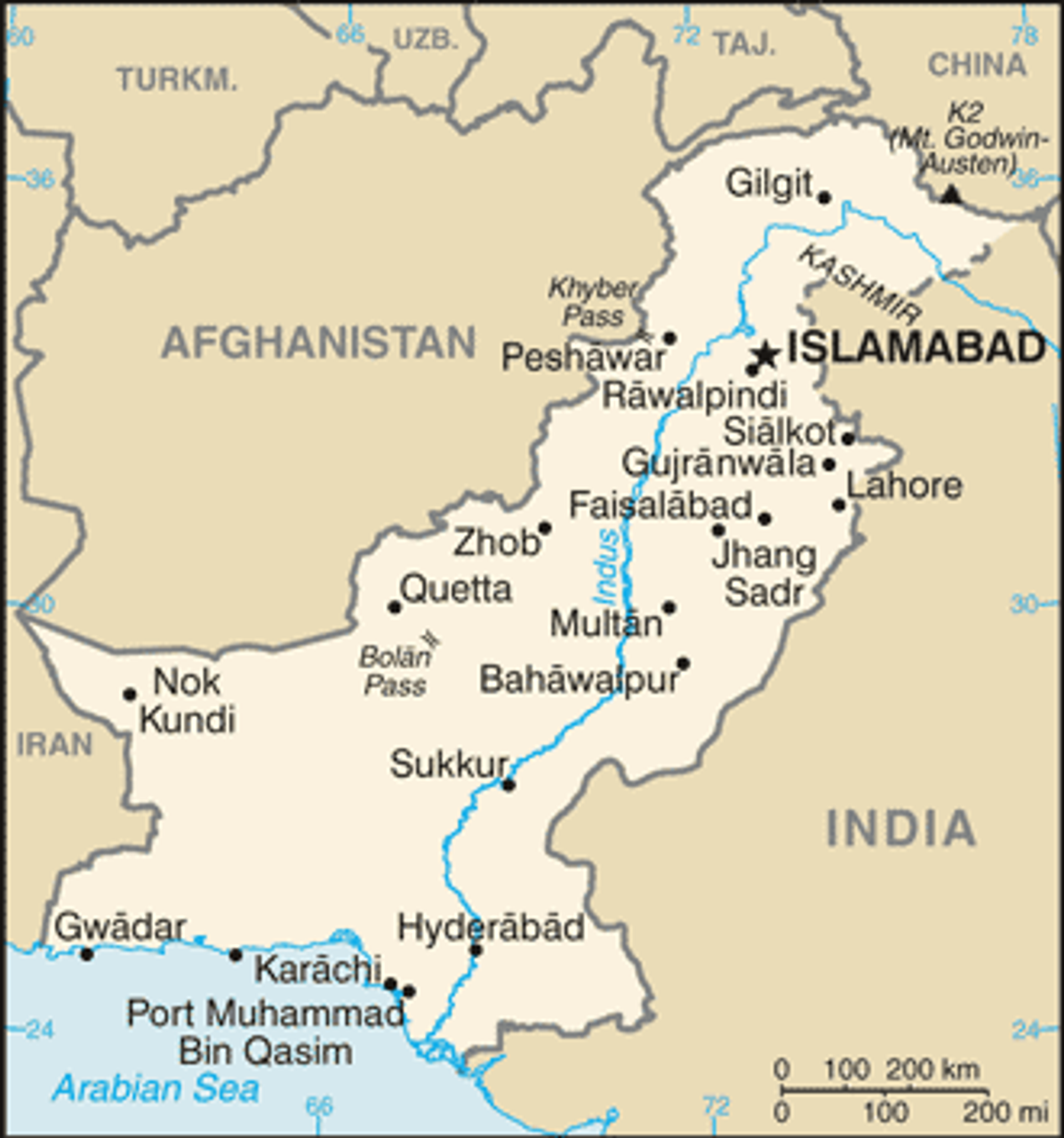

There were reports of protests in cities throughout Pakistan. Thousands of demonstrators gathered outside the US consulate in Karachi. Students blocked roads in Peshawar, chanting, “Quit the War on Terror.” Tribesmen gathered for a protest in Mohmand, the district where the raid took place. Lawyers struck or boycotted court proceedings in cities across the country, including Lahore, the capital Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Pakpattan, Multan and Peshawar.

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke with her Pakistani counterpart, Foreign Minister Hina Rabbani Khar, who said the Pakistani people felt a “deep sense of rage” at the attack. The chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Martin Dempsey, also spoke to his counterpart, Pakistani Army Chief General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani.

What happened during the raids is still disputed. NATO and the US Central Command have both announced investigations. Yesterday, press sources cited anonymous Afghan and Western officials who claimed that a joint NATO-Afghan patrol in Afghanistan came under fire from across the Pakistani border and called in air strikes that hit the border posts.

Pakistani army officials issued angry denials, insisting that the NATO attack was unprovoked and reports of an attack from Pakistan were invented. Major General Athar Abbas said, “This is not true, they are making up excuses. By the way, what are their losses, their casualties?”

Abbas added that the attack lasted two hours. He stressed that Pakistani officers contacted NATO and asked them to “get this fire to cease, but somehow it continued.”

Islamabad has retaliated by threatening to break diplomatic and intelligence links with Washington and ordering the US to vacate an air base in the Pakistani city of Shamsi, from which the CIA has launched Predator drone strikes inside Pakistan. It also shut border crossings between Pakistan and Afghanistan through which trucks ship supplies to US and NATO troops in Afghanistan.

China, a key Pakistani ally, said it was “deeply shocked” at the raid. Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi said China would “firmly support Pakistan’s efforts to defend its national independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity… This serious incident should be thoroughly investigated and be handled properly.”

The Pakistani government is signaling to Washington its concern that the Pakistani masses’ anger at its collaboration in America’s wars could lead to a political explosion in the country. Pakistani Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani gave an interview on CNN yesterday warning that the raid was stoking opposition to Islamabad’s unpopular participation in the NATO war in Afghanistan. He began: “You cannot win any war without the support of the masses, and we need the people with us. Such incidents make people move away from that situation.”

When CNN asked whether Pakistan would break relations with the US, however, Gilani demurred. He said, “We are just thinking of reviewing our relationship,” adding that relations “could continue based on mutual respect and mutual interest.” He said he would await recommendations from the Pakistani Parliament’s National Security Committee.

US media downplayed Pakistani criticism of the raid, however, writing that Islamabad would resume its collaboration with Washington. The New York Times wrote: “It does not matter whether the strikes are justified as self-defense or acknowledged as a catastrophic error… The damage to the American strategy has already been done, and the question is how long it will take for officials from both countries to resume cooperation where it is in their interest to do so.”

Fox News suggested that Pakistani capitalism’s financial dependence on Washington would keep it in line: “A complete breakdown in the relationship between the United States and Pakistan is considered unlikely. Pakistan relies on billions of dollars in American aid, and the US needs Pakistan to push Afghan insurgents to participate in peace talks.”

Fox added a dig at Islamabad’s for-the–record criticisms of NATO: “The drone strikes are very unpopular in Pakistan, and Pakistani military and civilian leaders say publicly that the US carries them out without their permission. But privately, they allow them to go on, and even help with targeting for some of them.”

The American ruling class is demanding that Pakistan fall into line with US strategy for the “AfPak” war. It wants Pakistan to use its ties to Islamist groups in Afghanistan to help the US negotiate a peace deal with the Taliban, while simultaneously helping the US attack Islamist insurgents on the ground in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Islamabad’s attempts to comply with US requests have increasingly brought it into conflict both with the US and Pakistani public opinion.

NATO forces in Afghanistan often come under fire from insurgents based in Pakistan, like the Haqqani Network, and it is widely reported that top Taliban leaders live in the Pakistani city of Quetta. US officials have tolerated Pakistani ties to these groups, which help guarantee that the US will have negotiating partners in a potential deal with the Taliban. However, Washington is angry at Islamabad’s continuing collaboration with Taliban forces in Afghanistan.

In September, the US opened a public rift with Islamabad when US officials blamed an attack on the US embassy in Kabul on the Haqqani network, which Adm. Mike Mullen called “a veritable arm of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency.”

The contradictory ties between the US, Pakistan, and armed Islamists in Afghanistan date back to the 1980s, when the US and Pakistan backed the Islamist mujahedin against the Soviet-backed Kabul regime in the 1979-1989 Soviet-Afghan war. The US and Pakistan later jointly backed the Taliban in the mid-1990s—trying to put Afghanistan under US control and open trade routes to the ex-Soviet republics of Central Asia.

The US turned on the Taliban and Pakistan after the September 11, 2001 attacks, however, demanding that Pakistan abandon the Taliban or be bombed back to the “Stone Age,” in the words of then-State Department official Richard Armitage. Elements of the Pakistani army still maintained ties to Afghan Islamists, as Washington knew, to counterbalance Indian influence and try to keep control of the troubled Afghan-Pakistani border region.

The US has turned against Islamabad, however, and Islamabad itself has faced a deepening internal crisis as the Afghan war spread into Pakistan and NATO became increasingly bogged down. Yesterday, the New York Times cited a Republican presidential candidate and former US ambassador to China, Jon Huntsman: “I would recognize exactly what the US-Pakistan relationship has become, which is a merely transactional relationship… And I think our expectations have to be very, very low in terms of what we can get out of this relationship.”

These tensions will be exacerbated by Islamabad’s shut-off of NATO supplies into Afghanistan. Before 2009, when insurgent attacks on supply convoys mounted in Pakistan, over 80 percent of NATO supplies transited through Pakistan. Now 31 percent is flown in and 44 percent arrives via the so-called Northern Distribution Network (NDN)—a collection of road and rail links from Baltic and Black Sea ports, via Russia and the Caucasus, then the Central Asian republics to Afghanistan.

Image source: CIA Factbook

Image source: CIA FactbookNonetheless, this means that 25 percent of NATO supplies transit through Pakistan and will be held up at the Pakistani border. A senior US official told the Wall Street Journal: “All the leaders on the US side are taking this very seriously. We always have alternatives in terms of logistics. It depends on how long it lasts as to whether or not there will be a longer-term impact.”

The central element driving Islamabad’s policy—a cynical mix of maneuvering and subservience to US bullying—is the fear of a revolutionary upsurge of Pakistan’s workers and oppressed masses. During the first weeks of the Egyptian revolution in February, Pakistan saw mass protests against CIA killer Raymond Davis, whom Islamabad released without trial after he shot two Pakistani youths in a Lahore market. This anger intensified in May when the US launched a raid deep into Pakistan to kill Osama bin Laden in the city of Abbottabad.

In recent years, the US also has forced Islamabad to mount major military operations along its Afghan border, displacing millions of refugees inside Pakistan. This compounds a disastrous social situation marked by mass unemployment, rampant electricity shortages, and floods that made millions homeless in both 2010 and 2011.

The government also fears losing control of the Pakistani army. Hasan Abbas of the US National Defense University’s College of International Security Affairs told Reuters: “The Pakistani military is clearly very angry at the turn of events, and the army’s top leadership is under tremendous pressure from middle-ranking and junior officers to react.”

This follows the recalling of Pakistan’s ambassador to the US, Hussein Haqqani, amid rumors he helped head off a military coup against the Pakistani government after the US killing of bin Laden.

From the outset, the WSWS exposed the lies of the Bush administration that its illegal invasion was an act of self-defense in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11.