General Motors has taken a series of steps over the past week underscoring its determination to weather a long strike and achieve a clear-cut victory over the United Auto Workers. As the impact of two local strikes in Flint, Michigan brought virtually all of the auto maker's North American operations to a halt, top management began digging in for a protracted struggle, while intensifying its public attack on the union.

General Motors has taken a series of steps over the past week underscoring its determination to weather a long strike and achieve a clear-cut victory over the United Auto Workers. As the impact of two local strikes in Flint, Michigan brought virtually all of the auto maker's North American operations to a halt, top management began digging in for a protracted struggle, while intensifying its public attack on the union.

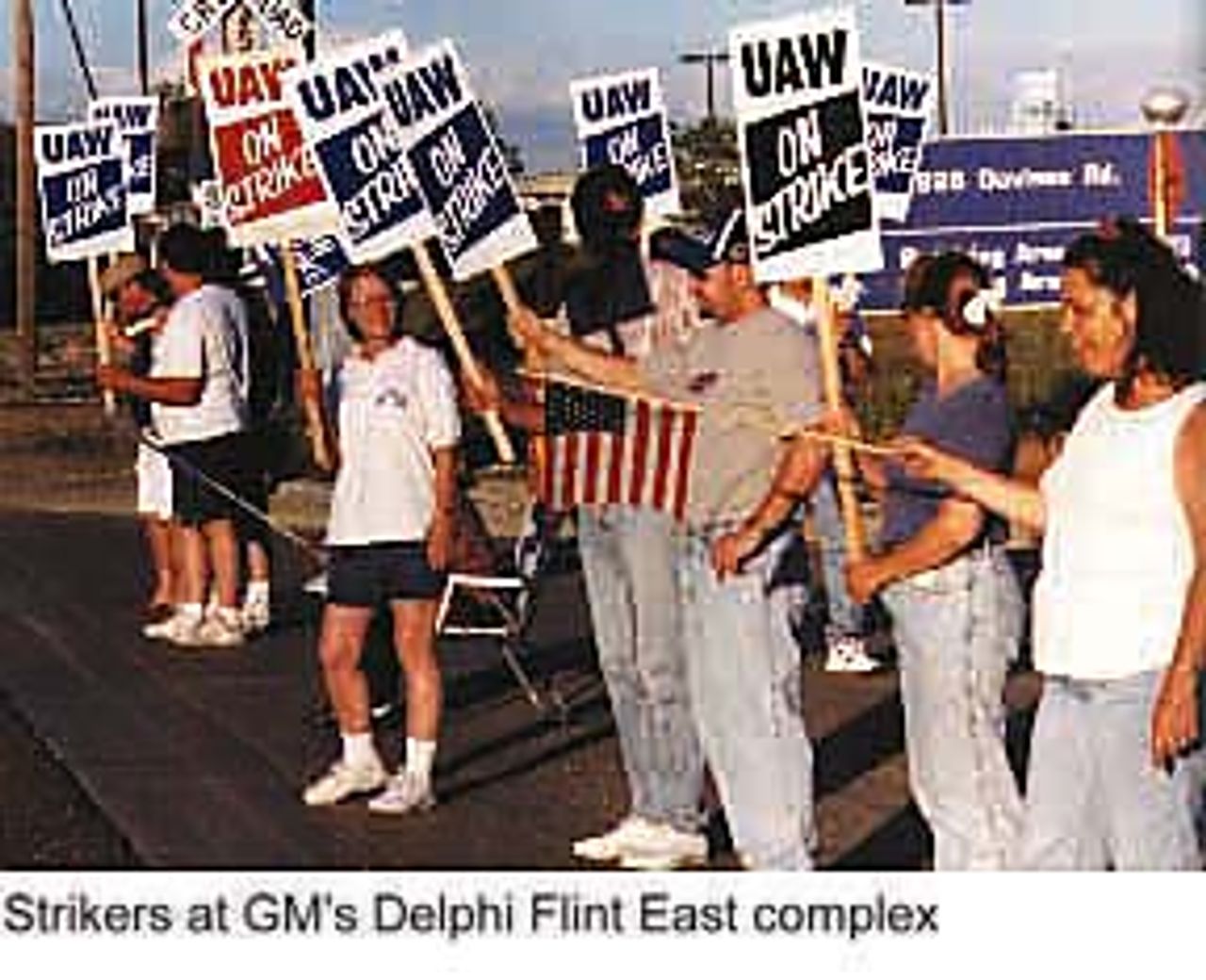

Early last week GM filed a grievance against the UAW, claiming the strikes at a metal stamping plant and a Delphi components facility were illegal. The union had called the walkouts, GM claimed, not because management had violated local contract provisions, but because the union was seeking to shift the company's global investment strategy.

While the striking workers can attest to a host of health and safety violations and a growing backlog of unresolved grievances, they know that the central issue is precisely the company's policy of slashing jobs, demanding ever-greater productivity and shifting production from traditional auto centers like Flint to take advantage of cheaper labor elsewhere. But the UAW was quick to deny that it was contesting the company's prerogative over investment, manning and overall corporate planning.

GM followed up its grievance by beginning a 'cold' shutdown of the bulk of its North American facilities. The company announced this unusual measure, which halts normal maintenance of idled plants and cuts the flow of electricity to a bare minimum, with considerable fanfare. Its transparent aim was to intimidate the workers and turn the confrontation into a quasi-lockout.

At the same time GM Vice President Donald Hackworth, who is in charge of the company's manufacturing operations in North America, ordered his subordinates to carry out a 50 percent cut in all discretionary spending. Since the strike began June 5 at the metal stamping plant, Hackworth has issued thinly veiled threats that the struck plants could be permanently closed, and GM executives have circulated a letter to white-collar employees hinting the same thing. In Dayton, the manager at two GM brake factories mailed letters to the homes of 3,400 workers on the eve of a June 29 strike authorization vote, warning about 'the consequences a strike could have for our plants.'

Finally, on July 1, GM terminated health benefits for the 9,200 workers at the two striking Flint locals.

The company's bellicose tactics indicate it has decided to pursue the current confrontation until the union publicly and demonstratively abandons any pretense of opposition to its cost-cutting drive. To this end Hackworth has singled out what the company calls 'non-competitive' work rules in the engine cradle department of the metal stamping plant, demanding that the UAW give up long-standing conditions there.

There can be little doubt that GM has been preparing over a protracted period for just such a confrontation. It is responding with cold calculation to the realities of a global auto market that cannot absorb the present level of capacity. To put it more plainly, there are far too many plants with too many workers producing too many autos for the existing companies to continue to sell their vehicles at a profit.

In the coming shakeout in the industry, only a handful of truly global companies will survive. No company, not even GM, is immune from the pressure of the capitalist market. GM feels this pressure very directly in the impact on its share values from the moves of big investors around the world--mutual funds, insurance conglomerates, bankers and billionaire speculators. The New York Times accurately summed up the connection between GM's hard-nosed tactics and the demands being placed on the company by global investors: 'It must convince skeptical institutional investors and Wall Street analysts that a settlement here will allow it to shrink its work force at other factories without further costly strikes.'

Recent events, above all the merger of Daimler-Benz and Chrysler, have reinforced the sense of urgency in GM boardrooms and convinced management of the need to accelerate its program of downsizing and cost-cutting. GM proceeds ruthlessly in accordance with its interests as a capitalist concern, guided by a strategy worked out on the basis of a considered assessment of global conditions. It exploits to the fullest the lack of any comparable strategy or preparation on the part of the UAW leadership.

Las Vegas convention

highlights UAW's crisis

Last week, while GM was issuing threats and gearing up for a decisive fight, the UAW leadership was assembled in Las Vegas for the union's 32nd constitutional convention. The meeting presented the spectacle of an organization responsible for the fate of 770,000 workers, in the midst of a bitter struggle with the largest industrial corporation in the world, and incapable of formulating a coherent strategy to defend the interests of its membership.

No one familiar with the record of the union over the past two decades would expect in its leading circles a similar level of consciousness, or a commitment to defend the interests of auto workers remotely commensurate with the single-minded pursuit of profit by GM management. Ever since it traded the jobs, wage levels and benefits of rank-and-file workers for a seat on the Chrysler board of directors in the early 1980s, the UAW has collaborated in a restructuring of the US auto industry that has restored the profits of the Big Three auto makers at the expense of hundreds of thousands of UAW jobs. Its corporatist policy of union-management partnership has in general served the short-term interests of the union bureaucracy. But it has increasingly undermined the longer-term viability of the union itself. With its membership roles and dues base already cut in half, the prospect of a further loss of 50,000 GM members over the next five years represents a mortal crisis for the UAW officialdom.

The UAW convention unfolded against this backdrop of declining power and the internal organizational strains that inevitably accompany such a crisis. All the more remarkable the utterly stage-managed and ceremonial character of the affair, dominated by the self-congratulatory rhetoric that has become the stock-in-trade of the trade union bureaucracy. There was neither serious debate nor vocal opposition. A diplomatic silence was maintained over the presence of UAW-GM logos and paraphernalia at the convention site. The election of the leadership's hand-picked slate of officers was a foregone conclusion.

In many ways, the keynote speech by UAW President Stephen Yokich expressed in the sharpest form the combination of blindness, complacency and political backwardness of the leadership, and the organic incapacity of the union apparatus to advance a viable perspective for auto workers. Yokich opened his rambling, hour-long address with a series of points pitched directly to the bureaucracy--the national and local officials and the hundreds of staff members who comprised the overwhelming majority of delegates and guests at the convention. In an effort to reassure them that he was looking after their special concerns, the union president began by reporting that the organization's assets had grown by $17 million since the last convention, three years ago.

Next he declared that the union was rebuilding its national headquarters in Detroit, Solidarity House, as well as the UAW's retreat at Black Lake in Michigan. He made a special point, as an example of how the union was forging ahead to prepare for the 21st century, of the renovations undertaken at the resort, frequented for the most part by union officials and their cronies among the membership. 'At a leadership meeting I got up and I said, 'We put full-sized beds in the bedrooms, and we put TVs in every bedroom,' and that was the loudest applause we got in the whole leadership meeting. We've been working out at Black Lake, we've been doing our thing.'

In remarks on the UAW's recent debacle at Caterpillar, the heavy machinery company that defeated the union in two bitter strikes between 1991 and 1996, Yokich again spoke quite openly from the standpoint of the bureaucracy. Explaining the decision of the union to end the strike in December of 1995 and order the workers back without a contract, he made a remarkable and damning admission:

'Do you know why? Because there were just as many workers that crossed the picket line as the good ones that stayed out there and marched that picket line and we were about to lose that strike.'

But despite the collapse of the strike, and the company-dictated contract that was ultimately imposed, Caterpillar was, according to Yokich, 'a damn win.' The reason? 'We still have union recognition.'

As opposed to the emphasis on Black Lake and similar matters dear to the heart of the officialdom, the current confrontation with GM barely rated a mention. It was raised in passing more than half-way into the speech. Yokich's only substantive comment was to insist, as against GM, that the shutdown was not a national strike.

As for the rest, the speech was a muddle of non sequiturs and contradictions. The twin pillars of UAW policy, particularly over the past two decades, have been corporatist union-management collaboration and economic nationalism. Yokich chose to remain silent about the disastrous results, for the rank-and-file, of the union's abandonment of any perspective of class struggle and its embrace of a policy based on the supposed identity of interests between corporate owners and workers.

But he could not ignore the obvious conflict between the union's nationalist orientation and the need for international unity in the struggle against an industry increasingly dominated by transnational giants. So he interspersed the standard UAW appeals to American nationalism with professions of concern for the plight of Mexican workers and promises to unite American auto workers with their brothers both north and south of the border.

Thus, he hailed the successful outcome of the union's essentially protectionist opposition to Clinton's bid for Congressional 'fast track' trade authorization, and declared the UAW to be a 'social movement' to stop US companies from shipping American jobs to 'Mexico or Asia or Indonesia or wherever.' But in the next breath he proclaimed the UAW's desire to 'help our Mexican brothers' and 'improve relationships with our brothers and sisters in Canada.'

How the UAW can unite American workers with auto workers in other countries while asserting that American jobs are more important and foreign workers should bear the brunt of corporate cost-cutting, Yokich did not say. GM, for its part, is well aware of this contradiction, and exploits it for its own purposes. In the current confrontation, they are telling their Mexican workers that the UAW is demanding the closure of its Mexican plants and the movement of production north of the Rio Grande.

As for the talk of better relations with the Canadian Auto Workers union, the very existence of a separate and rival auto union in Canada is the result of the nationalist policies of the Solidarity House bureaucracy, which led to the 1985 split-off of the Canadians from the UAW.

The hopeless inconsistencies and entanglements of the UAW's policy were most graphically expressed in Yokich's attack on UAW members who buy cars built by Mercedes-Benz. 'We should be telling them,' he declared, ''You shouldn't even be driving a Mercedes-Benz, you work for GM, you should be driving a GM product or a Ford product made by union workers in this country.''

Not ten minutes later he was hailing the merger between Daimler-Benz and Chrysler and boasting that the UAW had obtained a seat on the board of the merged corporation!

Even in relation to the UAW's alliance with the Democratic Party, the sine qua non of the union's political strategy, Yokich hinted, if only cautiously and indirectly, at the unraveling of the union's perspective. In the course of an attack on the Republicans, he inserted the qualifying phrase 'majority of the Republican Party,' and then alluded to the fact that the UAW's allies in its fight against fast track came primarily from the Republican side of the Congressional aisle.

The self-contradictory and muddled character of Yokich's speech was not simply the product of a limited intelligence. In fact, the contradictions themselves are not merely mental. They are rooted in a fundamental, objective contradiction that lies at the very heart of the UAW.

Like the rest of the AFL-CIO unions, the UAW has, in the course of its history of defending the interests of American capitalism, undergone a profound degeneration. It has become the apparatus of a privileged union bureaucracy, whose economic and social interests are distinct from and opposed to those of the mass of auto workers, and the working class as a whole. But the UAW bureaucracy, in order to defend its interests, must pose as the spokesman for the workers. Moreover it must, within the framework of an essentially nationally-based organization, seek to influence the policies of the auto companies so as to maintain the minimum dues base necessary to sustain the union apparatus.

In social terms, Yokich speaks not for the workers, but rather for a privileged, upper-middle class layer whose ample salaries and perks depend on its ability to prove its usefulness in keeping the working class in line. The central demand of the UAW leadership in the current struggle at GM is quite different from the aspirations and demands of the workers. The bureaucracy hopes to use the power of the workers embodied in the strike to pressure GM to 'work with the union.' It is not so much a matter of saving jobs, as saving the jobs and privileges of the bureaucracy.

This is why the UAW leadership continually counterposes to the 'pig-headed' attitude of GM the 'enlightened' labor policies of Ford and Chrysler (who, with the assistance of the union, shed a far greater proportion of jobs and plants in the 1980s than did GM). As Yokich told the press in the aftermath of the UAW convention: 'We have tried everything we can do to work with them (GM). I don't know--they don't want to work with us like the other auto companies.'

One salient fact highlights the objective contradiction between the interests of the UAW bureaucracy and the interests of auto workers. In announcing the increase in the union's assets since the 1995 convention, Yokich paid special tribute to those officials who worked on 'reinvesting our money.' An examination of the UAW's most recent filing with the Labor Department (March, 1998) indicates the substance of this reinvestment. For some time the UAW's net assets have hovered around the $1 billion mark, but until recently its investments consisted almost exclusively of US Treasury notes. Over the past several years, however, the union has shifted a growing portion of its wealth into corporate bonds, which it now holds in the amount of $249 million.

This change in investment policy has vast implications. It means that the financial solvency of the UAW is directly tied to the fortunes of American big business, as reflected in the fluctuations of the bond market on Wall Street. But the heady rise in the stock and bond markets in the course of the 1990s has been based on definite social policies, designed to foster what is generally called 'investor confidence.'

The essence of these policies has been the undermining of the social position of the working class. Unionbusting and corporate downsizing have shattered whatever economic security previously existed for tens of millions of working people. Social welfare programs have been gutted to increase the desperation of the most vulnerable sections of the working class, making them more exploitable as a source of cheap labor. These cuts in government spending have helped defray massive tax cuts for the corporations and the rich. The overall impact of these policies has been to suppress wages and increase the share of society's wealth going to the wealthiest five or ten percent of the population.

Such are the social and political conditions upon which the UAW bureaucracy has staked the future of the organization. Far from the union preparing for the 21st century by encouraging a growth in the unity and militancy of the working class, and basing its own fate on its ability to lead masses of workers in struggle against big business, it has a vested financial interest in precisely the opposite. Given the UAW's 'reinvestment policy,' is it any wonder that the union leadership is unalterably opposed to mobilizing the power of the working class in a serious struggle against the corporate attack on jobs and living standards?

In confronting the impotence and duplicity of the UAW, auto workers are compelled to consider the political roots of the failure not only of their own union, but all of the old labor organizations. All over the world the old trade unions and national 'labor parties' have led the working class to a dead end.

When GM declares that the real issue in the current struggle is how its resources are to be invested, it points to the essential question facing the working class. How, indeed, are the plant and equipment, financial resources and capabilities of millions of workers presently controlled by transnational corporations to be used and developed, not simply on a national, but rather on a global scale? Who is to decide, and on what basis?

In so far as the working class is held back by organizations rooted in a national perspective and an acceptance of capitalist private ownership of society's basic productive forces, it cannot put forward its own answer to these crucial questions. But that is precisely the task which the international working class faces--it must elaborate and fight for its own perspective for developing not only the auto industry, but economic life as a whole, in such a way as to meet the social needs of the masses of people and raise their material and cultural standard of living, rather than serving the insatiable profit drive of big business.

This is a political struggle, because it poses directly the question of which social class holds power. And it is an international struggle, because at the end of the 20th century the world economy has more completely than ever eclipsed the narrow confines of national enterprises and national markets.

The central issue that arises from the struggle of auto workers against the corporate onslaught on jobs and working conditions is the building of a new organization of working class struggle--a political party based on a socialist program and a strategy for the unification of the struggles of the working class internationally. This is the perspective fought for by the Socialist Equality Party in the US and its fraternal parties around the world.

This statement is available as a formatted PDF leaflet

to download and distribute

To read PDF files you will require Adobe Acrobat Reader software

(Download Acrobat Reader)

See Also:

Global changes in auto industry underlie struggle over jobs

[16 June 1998]

The merger between Chrysler and Daimler-Benz:

what it means for workers

[8 May 1998]