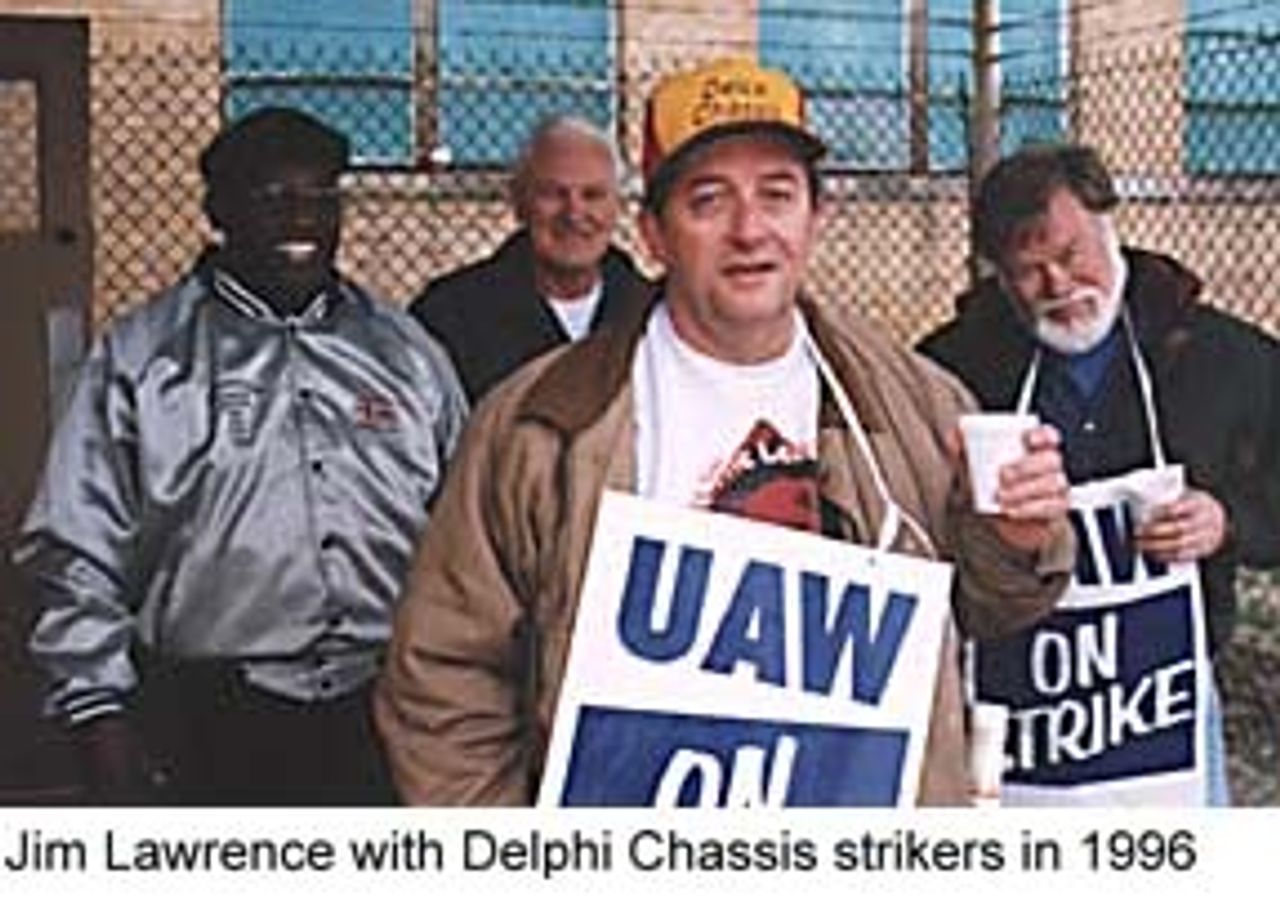

Below is an interview with Jim Lawrence, a recently retired GM worker from the Delphi Chassis (formerly Delco Moraine) brake plant in Dayton, Ohio. Lawrence is well-known among auto workers in Dayton for his militant defense of workers' interests and his principled opposition to the policies of the United Auto Workers bureaucracy. Lawrence was won to the socialist movement in the early 1970s. He is a member of the Socialist Equality Party in the United States. We urge workers to e-mail their comments to editor@wsws.org

WSWS: How did conditions change from the time you entered the factory to the time you retired?

JL: There have been many changes. I worked at GM's Delco Moraine plant from 1966 to 1996. When I hired in at the age of 27 there were a lot of young workers, not like today. We were elated to be hired because this was the plant where there were never supposed to be layoffs. It was the only brake-producing factory in the GM empire. We also thought we were joining the most powerful union in the world. The UAW had led the sit-down strikes in the 1930s and that was something that was still in the consciousness of the older workers.

In the 1960s there was something called 'make out,' which meant that after reaching your production quota in 4 or 5 hours, you could read the paper until you punched out. The speed of the assembly line was not so bad and you could comfortably keep up with the pace. Workers also had the attitude: 'I'll work for 20 years, then get a position as a job setter and spend the next 10 years sitting and drinking coffee.'

Today, the job setter is also a production worker. Production standards have increased incredibly. Even on jobs where there has been few technological changes, a worker's output has increased by 50 to 75 percent. Where new technology has been introduced standards have risen by 500 percent.

In the past, grievances were routinely won and GM conceded many things. If you said a job was unsafe because there was oil on the floor, the UAW would say you didn’t have to work. Now you could be working in asbestos-filled air and the UAW would tell you to continue working. None of this could have happened before 1975.

WSWS: What type of struggles were workers engaged in during the 1960s and 1970s?

JL: Many black workers were concerned about equality on the shop floor. The union gave foremen a blank check to mistreat blacks and keep them out of the high-rate machine jobs and the skilled trades. The same went for the younger white workers. If you were not part of the union's clique, you could not advance from the worst jobs.

Black workers organized a movement called “Second Family,” which was a mix of many different political ideas. Some workers were black nationalists, others militant trade unionists, and still others were attracted to socialist ideas. In 1968 we seized the personnel office at the plant and took a large number of workers to the union hall to demand an end to discrimination in the factory and the appointment of blacks to the union leadership. The union leaders responded by passing a resolution which they later repudiated and hiring security guards to protect themselves.

At the time many of the older white workers had come from Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia. It was not that they were all racists or white chauvinists, but they were used to a certain way of life. They were king of the hill and no black worker was going to climb from the bottom. In the late 1940s there were separate union meetings for blacks and whites. As late as the 1960s many blacks did not go to union meetings until a struggle for equality began.

After the urban riots, in addition to more black workers being hired, for the first time young white workers from Dayton came into the plant. They had a different mindset towards the race issue and there was a greater possibility of joining together to fight GM and the local union. I would say the most important change in my years was the level of agreement between black and white workers on the need to wage a common struggle against GM and the union bureaucracy. That was nonexistent when I hired in.

The 67-day strike in 1970 was another important struggle. We won back the cost of living increases that UAW President Walter Reuther had given up. We felt that we were invincible and could do anything. We had pride in being able to defeat GM, but we knew there was much more work to be done, especially with discrimination on the job.

These struggles were part of a wider, international, movement of the working class. Youth were opposing the Vietnam War, there was the civil rights movement and the general strike in France that nearly brought down the government. Many workers were radical in their ideas. This was the time that I turned to socialist politics and joined the Workers League, the forerunner of the Socialist Equality Party.

WSWS: When did working conditions and labor-management relations begin to change?

JL: In 1973 when the first oil crisis hit there was a recession and mass layoffs. The union began conceding to management's demands and started talking about working with the company to build a better product. At first the union's appeals failed. Whoever joined one of those 'Quality of Work Life' labor-management teams was ostracized and the whole thing collapsed. Workers considered management to be on the other side of the barricades, the enemy, and you just didn't cross over. During the Chrysler bailout of 1979-1980 there was a great deal of hatred for UAW President Douglas Fraser because he joined the company's board of directors.

The recessions of the mid-70s and the early 1980s hit workers hard. Many of the younger, most militant workers were laid off and the union did nothing to oppose it. Overtime was all but eliminated. The older workers wondered when they would get the axe. For the first time workers were concerned about their futures. Before it had been possible to walk off one job in the morning and get another by the afternoon. Now the union argued that we had to make concessions to save our jobs and get the unemployed back to work. Shortly after the Chrysler bailout the UAW reopened the contract at GM and gave major concessions to the company for the first time. We lost our paid personal holidays and suffered a wage freeze.

At the same time many of the older workers who were the militants in the late 1960s were given skilled trades or high-rate machinery jobs. Others got appointed to union positions. Management also hired a lot of former black militants as foremen. In a sense they were bought off. It was at that point that the militant resistance to GM subsided.

The concessions given up by the union compelled workers to labor longer hours just to maintain what they had. In many cases they had to help their children who could not find decent paying jobs. There was also a decline in class consciousness. In the early period of the recessions many workers would refuse to work overtime, until the unemployed workers were rehired. That was no longer the case.

WSWS: This was the time the UAW pushed its anti-Japanese campaign?

JL: The economic nationalism and chauvinism of the union bureaucracy really started with the oil crisis and recession of 1973. The UAW blamed the Arabs first and then later, the Japanese. After the oil crisis it was clear that the American auto industry had no small cars and the Japanese were in a position to gain market share. The UAW did not blame the capitalists or the Big Three auto companies. They blamed the Japanese companies and workers for 'stealing' our jobs.

UAW officials would not allow Japanese cars in the union hall parking lots. A Dayton union official named Wesley Wells organized the smashing of Toyotas and Hondas, and the union officials passed out bumber stickers saying 'Buy American' and 'Remember Pearl Harbor.' At this time a young Chinese-American named Vincent Chin was murdered in a Detroit suburb. He was killed by a Chrysler foreman and his son, who accused the 'Japs' of taking American jobs. His death was the result of the anti-Asian and 'buy American' campaign led by the UAW.

Large numbers of workers were taken in by the 'buy American' slogans. This played right into the hands of management, which had always sought to turn workers against each other. Before it was black against white and now it was American versus international workers. To assault the whole working class it is first necessary to drive a wedge between different sections of workers.

WSWS: What about the UAW's corporatist policy of labor-management cooperation?

JL: Just before some of the laid off workers were recalled around 1983-84, the UAW renewed its efforts to establish labor-management committees. They had to stop calling it the 'Quality of Work Life' program because every knew that the quality of work life was only getting worse. The UAW pushed production standards and brought in a new absentee program which gave management more power to discipline and fire workers. At the same time workers were being written up for 'restricting production' if they could not keep up with the pace of work.

In meetings management would tell these 'joint' committees what they wanted and then have them sign a piece of paper saying these were the ideas of workers. At one such meeting I posed a question. I said we would work together with management if they guaranteed us immediate raises and no layoffs, and if all disciplinary action would first have to be approved by a genuine workers' committee. This, of course, was rejected out of hand.

In each local union, the UAW bureaucrats want to see their plant survive so they can maintain their privileges, and they consciously bid against other UAW locals to keep up investments. We did the same work in Dayton as the Saginaw, Michigan plant, so the union officials said if we increased production we could get the contract from Saginaw. This was the union doing the dirty work for management.

When a group of workers from the closed Norwood plant were transferred to a GM plant in Indiana they were attacked for 'stealing' jobs. One worker was actually beaten to death while the others were denied housing in town. When they got a hotel room someone stayed up all night to be on guard.

WSWS: What did the Workers League fight for in opposition to the UAW leaders?

JL: The Workers League called for the building of a labor party by the unions and for socialist policies. In the early 1970s when workers were involved in major struggles with GM they felt they should take their fate into their own hands. If the unions were a powerful force, they figured, how much more powerful could they be with their own political party to fight for improvements for the working class?

In the early sixties and seventies, the UAW leaders said they were not opposed to a labor party, but that it was just not the right time. As the years went by, and the militancy of the workers subsided, the UAW openly said it opposed a labor party. This was at the same time the union was collaborating with the Democrats to attack the working class.

Socialist ideas were not popular with the broad mass of workers, who still associated socialism with the Stalinist dictatorship in the USSR and Eastern Europe. Only the most advanced workers considered themselves socialists. The union bureaucrats conducted a three-shift, 24-hour-a-day anti-communist tirade against supporters of the Workers League. They relied on red-baiting, not an open exchange of ideas, because our demands were on behalf of the working class, while the UAW leaders were selling out the membership.

We explained that there was an alternative to concessions and plant closings. The working class, we said, must not pay for the crisis of the auto industry and the capitalist system. If the auto companies were going bankrupt, they should be placed under workers' control and be organized as public enterprises to provide decent paying jobs and good cars. We also opposed the chauvinism of the union bureaucracy and fought for the unity of workers throughout the world.

The union leaders told workers if they listened to us and opposed GM everybody would be out of work. In the absence of a clear understanding of how to fight, workers swallowed the bitter pill of concessions and layoffs that the union pushed.

The history of the industrial unions in America shows that those people with socialist beliefs were the real organizers of the union movement. The driving out of the socialists from the unions during the red-baiting witchhunts of the 40s and 50s, and the opposition of the union bureaucracy to the building of an independent working class party based on a socialist program, has led to the sorry state of affairs today.

In 1996 I ran as the Socialist Equality Party's candidate for Congress in Dayton. I opposed the campaign of the UAW and AFL-CIO for Clinton and the Democrats, which included handing over $32 million to support their candidates. Many GM workers signed petitions to put me on the ballot, despite the union officials' opposition. They supported my campaign to build the SEP as a political alternative to the two big business parties and mobilize the working class to fight for decent jobs, health care, housing and education for all.

In 1996 I ran as the Socialist Equality Party's candidate for Congress in Dayton. I opposed the campaign of the UAW and AFL-CIO for Clinton and the Democrats, which included handing over $32 million to support their candidates. Many GM workers signed petitions to put me on the ballot, despite the union officials' opposition. They supported my campaign to build the SEP as a political alternative to the two big business parties and mobilize the working class to fight for decent jobs, health care, housing and education for all.

During this time we went on strike at the two Dayton brake plants for 17-days. The SEP fought for the mobilization of the entire working class against GM, but the UAW called off the strike just when it was having the biggest impact. Despite the union's claim that it had won 'job security,' a year later the company announced plans to shut one of our plants, eliminating hundreds of jobs.

WSWS: What do you think about the current strike in Flint and what advice do you have for the workers?

JL: Having gone through our strike in 1996 GM has prepared for this battle. Management is intent upon rationalizing its operations and establishing a certain rate of profit and market share. It will do this by shutting down 'unnecessary' plants and driving up the rate of exploitation of those workers who remain. The GM directors who were not prepared to do this were removed in 1992. This is now all-out class war.

The UAW bureaucracy, however, is chiefly concerned with defending its dues base and privileges. It is appealing to management, saying 'If you keep us around, we'll help you drive up productivity and profits.'

I don't think the younger generation of workers will go for that. They are not going to be as grateful to work in a GM plant as we were, nor are they going to have as many illusions in the UAW. The discrediting of the UAW bureaucracy is creating a vacuum and the younger workers are going to be looking for more radical solutions to fight for their interests.

The Daimler-Benz and Chrysler merger is a sign of the ongoing globalization of the auto industry, and also a sign of the worthlessness of the UAW. Despite all their anti-foreign chauvinism, they have nothing negative to say since they are getting a seat on the board of directors of the merged company. The worldwide integration of the industry is bringing the working class closer and closer. In and of itself globalization is not bad. The loss of jobs and downward spiral of wages is taking place because the globalization process is in the hands of the class enemy, the capitalists, who are using it for their benefit against the workers.

The only way workers in America or any other country can fight against the shifting of production to low-wage areas is to fight for a strategy that unites workers of all countries against the transnational corporations. Workers should be outraged that GM is throwing higher paid workers out of their jobs in the US, but they should be no less outraged that the exploitation of the Mexican workers is so great that they can be used as a source of cheaper labor. Mexican workers are a section of our class and we must do everything to unite with them against the horrific conditions and inhumane conditions they confront.

When the UAW leaders attempt to mask over their American nationalism with verbal statements of sympathy for the Mexican workers it is completely hollow. The only way to unite with workers below the border is to join them in a common struggle against the profit system itself. The UAW in practice helps management divide us and keep us from fighting the companies together. How many anti-Mexican statements made by the UAW do you think GM management is circulating around the Mexican plants?

The 'America First' policy of the UAW is a reflection of the union officials' profound ignorance. GM is a transnational corporation. Its investors come from all parts of the globe and it is to these investors that management answers.

This process shows the need for the international organization of the working class into a party that fights to use the advances in technology for the benefit of society as a whole, not the capitalist owners. That is what the SEP in the United States and our sister parties throughout the world fights for.