Capitalist ruling circles and world financial markets are increasingly being gripped by a sense of bewilderment, fear and even outright panic as the far-reaching implications of the deepening global economic crisis become ever more clear.

Two major concerns have arisen. Firstly, that the financial crisis will now rapidly translate into a world slump on a scale not seen since the 1930s, and secondly that it will be accompanied by government controls on the movement of capital and currencies of the kind imposed last week by Malaysia. Some economists have likened Malaysia's move to the infamous Smoot-Hawley trade restrictions imposed by the US in 1930, which played such a devastating role in the collapse of international trade.

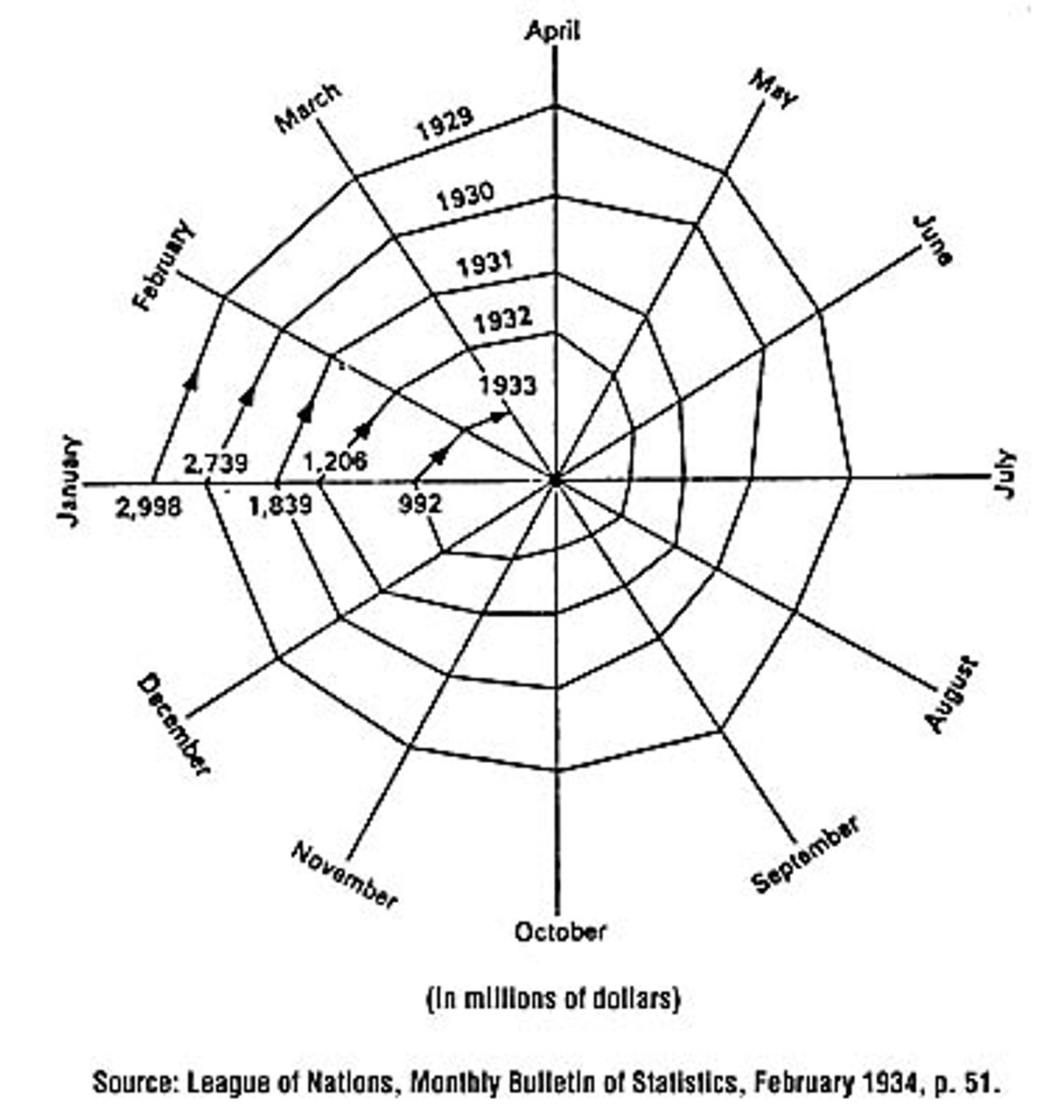

In its current issue BusinessWeek published what it called a 'graphic reminder' of what could go wrong--the famous cobweb diagram published by the League of Nations in 1934 showing how total world trade shrunk from $3 billion in January 1929 to a third of that level just four years later. While insisting that 'global depression' was not 'on the horizon', it nevertheless published the diagram to warn that there was 'little room for error in times such as these' and that with 'a few missteps ... problems can turn into disasters.'

The growing divisions between the major capitalist powers and the absence of any plan of action to meet the worsening economic and financial crisis were highlighted in a report of Friday night's discussions in San Francisco between US Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and Japanese Finance Minister Kiichi Miyazawa published in the New York Times.

It noted that the participants left the following morning 'with no new plans, and an uneasy sense that Japan and the United States remain on different wavelengths about how quickly countries must act.'

American officials said they feared that Japanese leaders did not accept the premise that the Japanese banking crisis was a major cause of the turmoil on world markets, while Japanese officials were said to have 'bristled' at mounting American pressure.

In an indication of the rising tensions, the Times quoted an unnamed senior Japanese financial official who expressed concern that 'if anything happens to the US economy, everyone will point to Japan and say it is responsible.'

In a speech delivered prior to the discussions, US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan gave his strongest indication yet of the threat of recession, saying it was 'just not credible that the United States can remain an oasis of prosperity unaffected by a world that is experiencing greatly increased stress.'

Rubin described the situation as unprecedented 'in a host of respects'. 'The number of countries experiencing difficulties at one is something we have not seen before.'

According to the Times, neither Greenspan nor Rubin has used the phrase 'global recession' out of fear that it might provoke further turmoil and become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The report also cited remarks by Jeffrey Garten, the dean of the Yale School of Management and a former top official in the Commerce Department, who said the views of a few months ago that there was light at the end of the tunnel had changed.

'Now the only hope is keeping the world economy from total deterioration. And you get a sense that this is all now truly left to Adam Smith's invisible hand--it's beyond any country's ability, any institution's ability, to control.'

Similar sentiments were expressed in a recent article in the most vociferous proponent of the 'free market,' the Wall Street Journal.

'What makes the crisis so unnerving,' it commented, 'is that there is no clear solution in sight--no financial firebreak that governments or international institutions can construct to slow the spread.'

On the other side of the Atlantic, a Financial Times editorial published last Saturday pointed to the 'threat to globalisation' arising from decisions in Asia.

'Malaysia's imposition of capital controls and Hong Kong's intervention in its stock market have planted worries that we may be entering a very different environment, where the supremacy of markets is questioned and protectionism makes an unwelcome return.'

The growing concern is not confined to major media outlets. For example a recent executive summary prepared by well-known business economist, Allen Sinai, for the investment information group Pridmark Decision Economics noted: 'With the Asian crisis historically unprecedented, new financial and credit problems cropping up in developing countries and policymakers around the world at a loss to figures out what is going on, why, and what to do about it, more of the same lies ahead, with financial markets likely to keep cracking new territory.'

Besides its editorial, BusinessWeek, issued a major commentary calling for emergency measures by the US Federal Reserve and the major world powers to halt the global crisis, which reflected the deep-going political crisis gripping ruling circles.

'Has the global economy come undone?' it asked. 'Is the American model of free-market capitalism, the de facto ideology of the post-cold-war period, in retreat? There are many messages in the recent volatility of the stock market, but the most important may be that fundamental assumptions about the future of the American economy have been completely altered by the crises in Asia and Russia. Stock prices are reflecting a world that appears to be headed towards a deflationary slowdown, a world where countries are opting out of a free market system that everyone took for granted. ...

'It is clear that the contours of the crisis are different from anything we've seen in a long time. In severity and speed, it has taken most economists totally by surprise. Its deflationary core has unsettled policymakers accustomed to a lifetime of inflationary problems. The erosion of pricing power is startling corporate managers. Repudiation of debt is terrifying bankers.'

It pointed that whereas for the past decade, 'the triumph of free markets appeared inevitable,' a new mood had begun to take hold.

'Everywhere, the free market is increasingly perceived as the enemy of growth, Increasingly, nations are opting out. This retreat from the US model is a reaction to one of the greatest episodes of wealth destruction ever. In the past year, market declines of 50 percent, 70 percent and even 80 percent in Asia have wiped out hundreds of billions of dollars in asset wealth. Then the real economy collapsed. The Korean economy has contracted 5 percent over the past 12 months, Thailand is down 10 percent, Indonesia nearly 20 per cent. Some 100 million middle-class people are being pushed back into poverty.'

With Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe expected to have added more than half the growth in the world economy, action had to be taken to 'rescue Asia's middle class' or the consequences for global growth would be 'immense,' cutting profits for corporations around the world and increasing 'global political instability'.

But it was the 'solutions' advanced by the magazine, even more than the facts and figures it cited, that indicated the depth of the crisis in ruling circles.

First of all, it insisted, 'the slide' had to be stopped. 'Someone must get in front of the TV cameras and say: 'Enough. We have a plan.''

But what is that plan to be? According to BusinessWeek, more of the same. The answer, it said, was not to restrain the market and impose curbs on capital and currency flows but the opposite.

'We think the solution is more integration, not less: more political reform within each emerging market, not more regulation of the global capital system.'

But in advancing this 'solution', the author, unknowingly, pointed to why the magazine's call for coordinated action, involving Rubin and his counterparts in Germany in Japan, cannot be implemented.

Far from representing a plan avert a world economic crisis, the call for the further advance of the free market juggernaut reflects the direct and immediate interests of the US banks and financial institutions. Their drive for profit demands the opening up of the markets of US rivals and the destruction of vast amounts of foreign-owned, and especially Japanese, capital.

As Japanese Finance Minister Miyazawa was at pains to emphasise following his discussions with Rubin, the bankruptcy of the Long Term Credit Bank in Japan, which the advocates of the free market are demanding be liquidated, 'might result in systemic risk for the United States and Japan'--that is, a crisis of the global banking system, not merely the collapse of individual banks.

It is doubtful if the Communist Manifesto is the subject of close study at BusinessWeek, but its description of the economic situation in the United States, and indeed in every country around the world, recalls the analysis of Marx more than 150 years ago.

'Corporate America,' the magazine explained, 'may soon be faced with too much of everything--plants and equipment, workers, managers, suppliers. There is a discontinuity in the global system. Everything has changed.'

Or, as Marx put it, in the crises of capitalist society, 'there breaks out an epidemic that, in all earlier epochs, would have seemed an absurdity--the epidemic of overproduction ... it appears as if a famine, a universal war of devastation had cut off the supply of every means of subsistence; industry and commerce seem to be destroyed: and why? Because there is too much civilisation, too much means of subsistence, too much industry, too much commerce.'

The eruption of a crisis, Marx explained, signified that the productive forces of society had become too powerful for the conditions of bourgeois property.

Therefore the solution to the crisis lies neither in the market nor in the imposition of national controls--both are roads to increased economic and social devastation--but in the overthrow of capitalist property relations worldwide by the unified action of the international working class.

See Also:

Intense conflict over Japanese bank 'restructuring'

[4 September 1998]

International market turmoil: A sea-change in world economy

[28 August 1998]