Double Happiness is a Warm Gun is the name of a recently concluded exhibition by Guo Jian at Sydney's Tin Sheds Gallery. Defined as 'Political Pop' in his native China, Jian's work, and this particular genre, is part of a rich and broad-ranging stream of artistic work being produced by artists from mainland China.

Double Happiness is a Warm Gun is the name of a recently concluded exhibition by Guo Jian at Sydney's Tin Sheds Gallery. Defined as 'Political Pop' in his native China, Jian's work, and this particular genre, is part of a rich and broad-ranging stream of artistic work being produced by artists from mainland China.

Jian, who now resides in Australia, participated in the Tiananmen Square protests--the mass movement of students that erupted against the Chinese Maoist bureaucracy in 1989. Jian's paintings angrily satirise the Maoist regime but his work raises questions of a more universal character, in particular, how governments and the media manipulate public opinion; and the social consequences of societies whose only moral value is the pursuit of money.

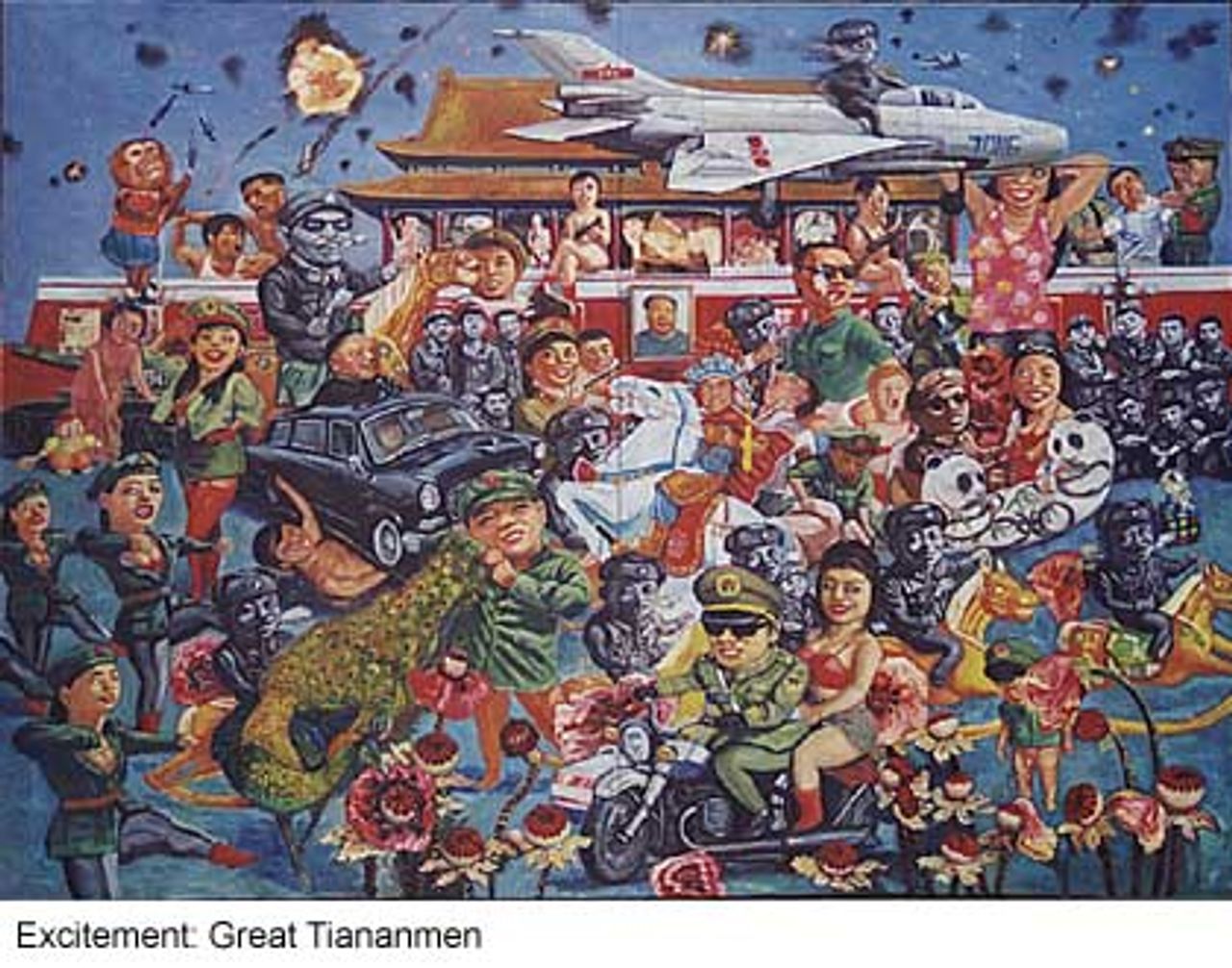

Larger pictures in the exhibition consist of almost comic book landscapes populated by a chaotic collection of characters--soldiers, generals, government bureaucrats, police, bar girls, strippers, young men and women on motorbikes, even panda bears and monkeys. Military hardware abounds with tanks, jetfighters and other weapons scattered throughout the images. Groups of soldiers clutch packets of Double Happiness--the local cigarettes.

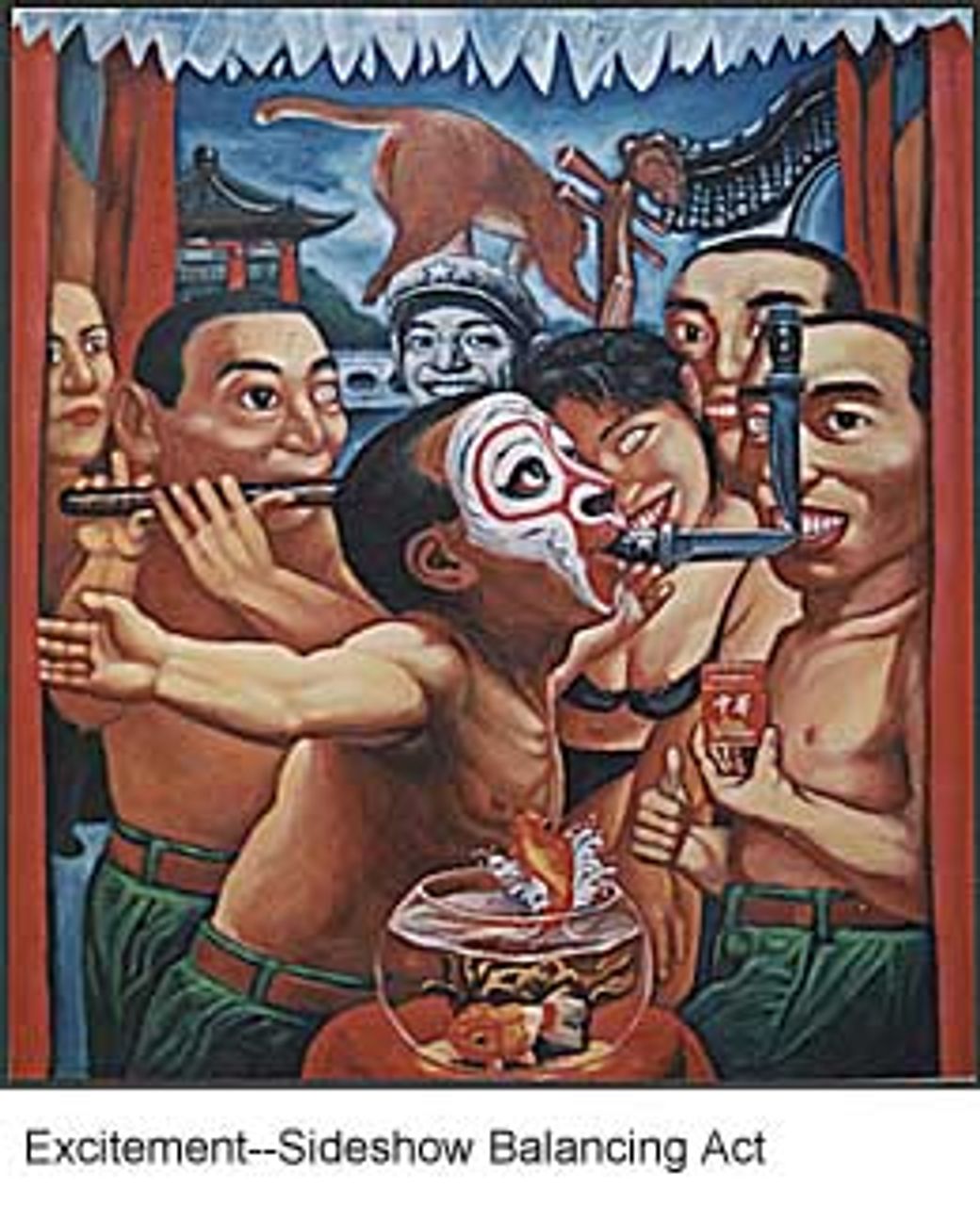

The more complex, intense and ultimately more disturbing images are the smaller paintings in the collection. These have a slightly more traditional feel about them with some of the characters performing circus acts.

'Excitement--Bowl Balancer' has six soldiers, a government bureaucrat, and a general watching a young woman balancing on one hand, whilst juggling bowls in the other. 'Excitement--Sideshow Balancing Act', perhaps the most unsettling image in the collection, has a half-naked Red Army soldier, his face painted with a traditional mask juggling a military knife in his mouth.

'Excitement--Bowl Balancer' has six soldiers, a government bureaucrat, and a general watching a young woman balancing on one hand, whilst juggling bowls in the other. 'Excitement--Sideshow Balancing Act', perhaps the most unsettling image in the collection, has a half-naked Red Army soldier, his face painted with a traditional mask juggling a military knife in his mouth.

'Excitement: Qigong', consists of six soldiers smoking cigarettes and observing a strangely beaming young woman in a bikini, lying on her back as a government bureaucrat chops cabbage with a hatchet on her stomach. While everyone is laughing hysterically, or in a state of almost beatific bliss, an atmosphere of hypocrisy, lying and tackiness prevails. The overwhelming mood is dark and disturbing, the scenes dominated by an underlying sense that something terribly barbaric and violent is about to occur.

Guo Jian spoke to the World Socialist Web Site about the social and political conditions facing artists in China today and the evolution of his own artistic vision.

Richard Phillips: Why are there so many military references in your paintings?

Guo Jian: I spent three years in the army and it had a big impact on me. I've used the images and faces from that time because I want my paintings to be emotionally true and to express my own experiences.

I come from a remote area in southwest China near the Vietnamese border. After the war began with Vietnam in 1979 the military came to our town recruiting--they needed lots of soldiers. I joined, pleased at first because I thought I could obtain my independence and some freedom. Maybe I was a bit naive but I thought that soldiers should help the people. This is not what I saw.

I come from a remote area in southwest China near the Vietnamese border. After the war began with Vietnam in 1979 the military came to our town recruiting--they needed lots of soldiers. I joined, pleased at first because I thought I could obtain my independence and some freedom. Maybe I was a bit naive but I thought that soldiers should help the people. This is not what I saw.

I witnessed many terrible things. I saw how the government indoctrinates its soldiers, how it uses nationalism to blind and divide people, and I saw a lot of suffering and fear. We were like toys in the hands of the government--pushed from one place to the next and constantly told we should be satisfied and happy. Prior to the war we were told that the Vietnamese were our friends. Suddenly the policy changed and they became our enemies.

The government does everything it can to manipulate opinion. One day some people are heroes, the next they are subhuman enemies. One day the government can order its soldiers to carry out a massacre, a few years later it can apologise to the survivors and blame the soldiers for the terrible events.

I saw tremendous suffering. New recruits sent straight to the front-line. I met one young soldier who had been shot in the head. He survived but had completely lost his memory. Another time I went to a military hospital with a friend to visit soldiers seriously wounded by land mines. Many had their legs amputated, couldn't face their families, and had gone crazy. The government and the military looked after them to keep things quiet but this hospital was a horrifying place. It really shocked me.

RP: But why do most of the soldiers in your paintings have happy faces?

GJ: This is connected to how we were trained, not just in the army, but in China. There are not supposed to be any problems in life, everyone is supposed to be happy. The government orders happiness--if you are not happy then we will make you happy. This is what I am trying to show in my work--that this happiness is not real, that it is forced, almost as if drugs artificially create it. The exhibition is called 'Double Happiness' to emphasise this false reality.

RP: After leaving the army you worked at a local factory in Duyun, your hometown, and later gained entry to the Beijing Minorities Institute to study art. During the Cultural Revolution the government denounced all Western art as bourgeois and reactionary. Had you ever seen any contemporary Western art?

GJ: All I had seen were some prints. I didn't get a chance to view any modern art firsthand. When I came to Beijing there was some freedom for artists and the first foreign exhibitions were being held. This was the first opportunity I had to view original Western contemporary art and I visited the Robert Rauschenberg exhibit. This shook up all of us. I also saw Picasso and Matisse for the first time.

Even though it was expensive, tens of thousands of people visited the Rauschenberg exhibition. I went with my friends and lots of students came from my college and other art schools. We came away very disappointed about what we had been doing and wanted to change everything.

Art in China had been mainly for propaganda purposes. Suddenly all the art students wanted to produce completely different work. Many students began copying contemporary Western art and in 1989, the same year as the Tiananmen Square protests, there was a special exhibition of contemporary Chinese art with many interesting works.

Art was one of the ways in which the government was being challenged. This exhibition was attended by thousands of people. This made the government very nervous and it eventually closed the exhibition.

The arts students began to come into conflict with the old generation of artists. Some students were expelled from college because they didn't agree with the official government-sponsored art. Some young critics travelled around China giving lectures on the new art. It was like an intellectual revolution and it seemed to me that there were signs that some artists would be given some new freedom. I remember feeling very excited and lucky to be part of this change.

In 1986-87 there had been some demonstrations. I recall the students marching past our college but the head of the university was strict and ordered the gates shut to prevent the students joining the demonstrations. This was the first time I had seen a student demonstration in Beijing.

This spirit was present in the protest movement that began in Tiananmen Square in 1989. I joined the Tiananmen Square protests and participated in the hunger strike.

The Communist Party officials often used to speak about the demonstrations and revolutionary struggles they had been involved in when they were young. Now they were opposing similar action by a new generation. It was like a repeat of history, except this time the Communist Party opposed the protests. There were plainclothes police and intelligence people everywhere but more and more students. Thousands joined and we had support from workers and many other people. It seemed that our generation would win freedom for everybody.

Articles began appearing in the newspaper attacking the students and ordering them back to school and university. The duty of students, the government said, was to study. I knew that Deng Xiaoping would not make any compromise; that the government was preparing something very bad, but when you saw hundreds of thousands of people you thought that maybe the government would not be able to do anything. And because we didn't know the real history of the government and the fact that they had killed so many people before we were not prepared.

On June 3, I was in Mu Xi Di, a suburb southwest of Beijing, when the army started shooting. This was where some of the worst shooting took place. I really couldn't believe the extent of the violence. A friend and I took refuge in a hospital and saw many people dead and injured. People were dying beside us so we tried to rescue people from the street but the soldiers kept firing. It was a terrible scene and one that I can never forget.

RP: You mentioned that there had been a brief period of liberalisation or creative freedom for artists and writers prior to the Tiananmen Square protests. What happened after the protests?

GJ: Before the 1989 massacre the teachers had been quite good. Of course some had narrow minds but some tried to be more open towards us and our ideas. This quickly changed after the massacre. The government and the authorities began lying again and there was repression against the students and workers who supported them.

The atmosphere became very bad and the teachers started to get scared. Artistic work was pushed back, and although it was not a return to the Cultural Revolution there was still an atmosphere of fear. Modern art exhibitions could not be held.

We didn't want to go back to the past and so artists who decided they would not be dictated by the government went underground. Many began to develop their own visual language--their ideas and thoughts disguised so that government officials and the police could not recognise the real meaning of the work. A new symbolism emerged.

At the same time the government did everything they could to attract company investment into China. Art dealers from Taiwan, Hong Kong and America began taking an interest in contemporary Chinese art. This made it possible for some artists to exhibit with shows in foreign embassies, international company offices and in private apartments. Others were able to show their work outside China.

RP: What problems did you encounter?

GJ: Although I was allowed to graduate I ran into problems with the party cadre at the college. I had been in charge of a class and was instructed to report what the students were doing each week. There were nine students in my class--how could I report on them? They were students, not international spies. I didn't agree with this at all.

Students are supposed to be offered a job when they graduate but the job they offered me was in a remote village in Guizhou, far from Beijing, in a machinery shop. I refused this and moved to Yuanmingyuan, a village on the northwest outskirts of Beijing, in July 1989. Housing was cheap, the villagers needed money and didn't care whether we had ID or not, so many students moved in. It became known as Yuanmingyuan Artists Village. I lived there for three years. Before I left there were about 60 artists. This later grew to 200--painters, musicians, writers and poets.

RP: And the government reaction to this?

GJ: The government found out and the police started coming around. At first they were not concerned about what we were painting--we were using visual symbols they didn't understand--but their attitudes began to change. Although they would ask the same questions--what are you painting, what new works do you have, etc.--it would be more threatening. They would come equipped with electric batons and in the middle of the night because they didn't want the local villagers to know it was happening.

I applied for a visa for Australia and they wanted to know what the letters were all about and why. This sort of harassment went on all the time--1989, 1990, 1991.

RP: Were any artists arrested? What were the charges?

GJ: Yes, there were arrests but the charges were always over stupid things. A sculptor I knew found some stone to work with. Unfortunately the stone had been part of the old imperial palace. The police claimed he had stolen it and said he had to pay an outrageous fine, an amount that was impossible. Eventually the police were bribed with a smaller amount of money.

One artist got into an argument with the police who had been harassing him. He was violently beaten and taken to court, but the attack was so obvious that a policeman was charged and jailed for a year. One week later the artist was arrested. The police claimed he had stolen a bicycle. He was put in a government re-education camp for three years. I have no doubt that the policeman was secretly released.

RP: You immigrated to Australia in 1992 but then decided to return to China in 1995.

GJ: I wanted to begin work again in the village. Unfortunately, the police harassment continued, nothing had improved. In June 1995 the police said we all had to move out of the village. We ignored this at first but then the government sent soldiers and placed them on guard outside the village. My friends had established a community restaurant in the village. The police closed it down. Eventually the artists began to move out. Those that didn't were arrested and sent back to their homes.

RP: What is the situation confronting artists in China today?

GJ: I haven't been there for three years. Of course it is still difficult to publicly voice your opinions about the government and impossible to exhibit the sort of work I do. You can paint, but no-one will show it--the police will close the exhibition.

There are many problems facing artists in China. The government directs what artists can do, at the same time it tells people to make money and do it as quickly as possible. Now, after wealthy foreign dealers became interested in contemporary Chinese art, there is the influence of the capitalist market. All of this is destructive to the production of genuine creative and honest work.

Pepsi is an interesting symbol for me. In Chinese the word means 'anything goes'. This really sums up the situation in China today--get rich anyway you can, it doesn't matter how. This is the outlook of the government and many people in China--they don't care about the consequences.

The government says everyone should make money--to get rich is glorious. All this means is that there is a tiny group of wealthy people but the majority are poor. Although only a minority gets rich, the culture is used to try to convince people that everyone can. This is like the early days of Western capitalism--a desperate scramble for money--and the same process is happening in Russia.

Some people realise that there is more to life than these values but others who don't understand what is happening, and fear what the future may bring, have turned to religion.

For my next project I'm thinking about the drugs culture and the ideology associated with this. This is a real problem in my hometown--people are dealing drugs and many more are addicted.

RP: What work should artists be producing?

GJ: I don't venture an opinion on this but I have strong feelings about my own work. I have witnessed many disturbing events and feel deeply about many social and cultural questions. My paintings are not just about China but the overall human situation. Injustice is going on everywhere so I feel a responsibility to tell people the truth, and I want my work to affect people.