A rare exhibition of photographs of the Spanish Civil War taken by Hungarian photojournalist Robert Capa is being shown at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia (Queen Sofia National Museum Arts Centre) in Madrid. Entitled "Face to Face", the exhibition runs until April 5, 1999.

The popularity of the show means it may well be extended or re-staged. Huge crowds have flocked to see the pictures, with long queues waiting for hours at weekends. Within two weeks of opening, every single copy of the catalogue accompanying the exhibition had been snatched up, even those in foreign languages.

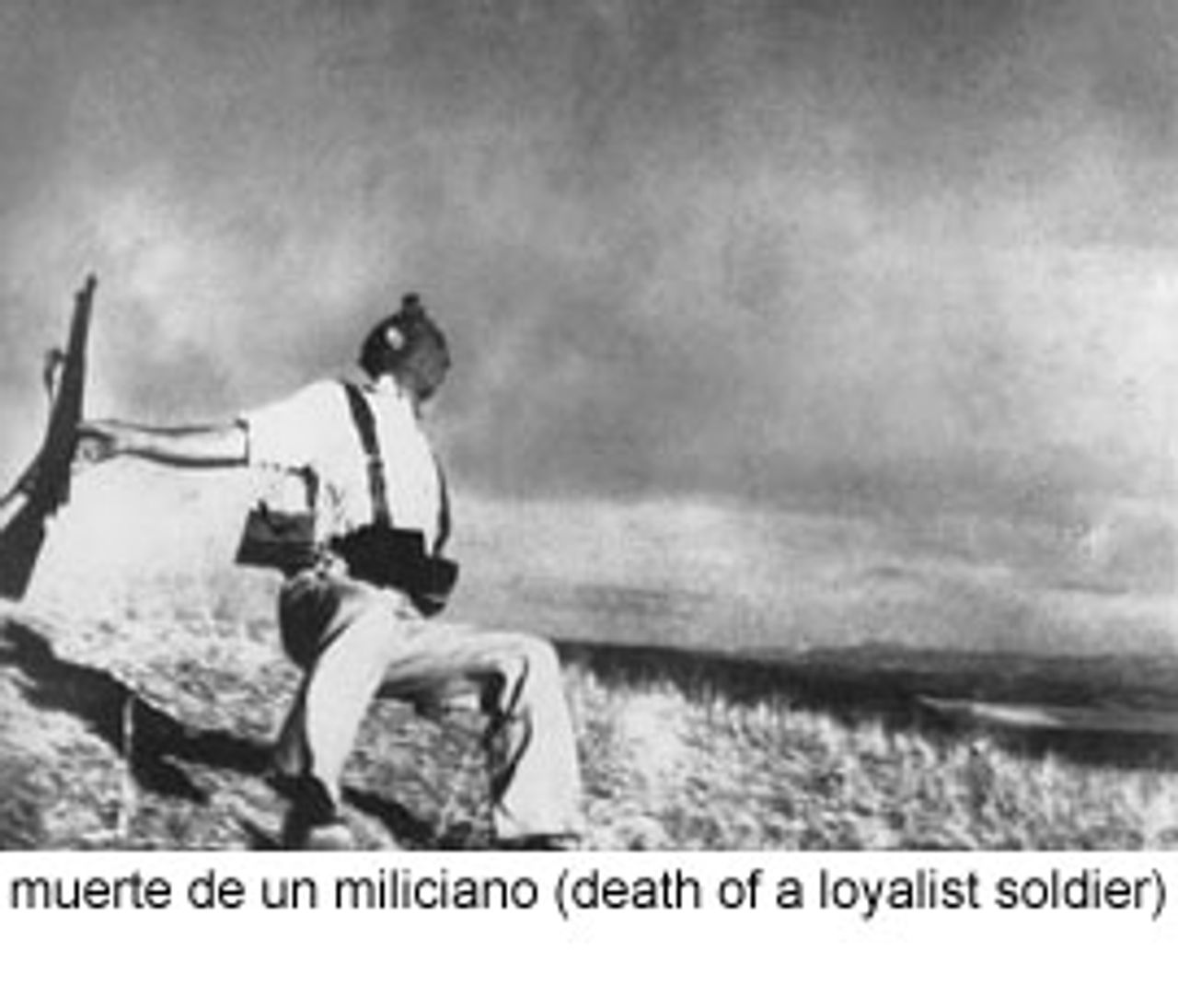

Capa's photographs capture different aspects of the civil war in Spain, as well as its impact on and the involvement of the civilian population. Amongst Capa's works are world famous photographs, such as the 1936 "muerte de un miliciano" (death of a loyalist soldier), perhaps the most symbolic image of this struggle, after Picasso's "Guernica", which can also be seen on the second floor of the museum. Scan courtesy of Masters of Photography

Capa's photographs capture different aspects of the civil war in Spain, as well as its impact on and the involvement of the civilian population. Amongst Capa's works are world famous photographs, such as the 1936 "muerte de un miliciano" (death of a loyalist soldier), perhaps the most symbolic image of this struggle, after Picasso's "Guernica", which can also be seen on the second floor of the museum. Scan courtesy of Masters of Photography

The exhibition was made possible after Capa's brother, Cornell Capa, donated 205 photographs to the people of Spain. It also includes 22 photographs that were found in a suitcase belonging to the president of the Council of Ministers of the Second Republic, Dr. Juan Negrin.

Capa is considered one of the best war photographers. He first reached fame with the images he captured during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39). He also worked as a war photojournalist in China, capturing the movement of resistance to the Japanese invasion (1938), aspects of the Second World War (1941-45), the first Arab-Israeli war (1948) and the Franco-Indochina war (1954). He died in Vietnam in May 1954 when he stepped on a mine during his coverage of the French manoeuvres in the Red River for Life magazine. He was just 40 years old.

Capa was born André Freidmann in Budapest in 1913. As a result of his participation in protests and demonstrations against the dictatorship and his Jewish descent, he was forced to go into exile in 1931. He travelled to Berlin, where he studied and took part in discussion groups and conferences organised by Karl Korsch, a leader of the Communist Party, before he was expelled for adopting a critical position against the policies of Stalin.

The economic depression meant Capa was forced to leave his studies and take up a job as a messenger boy and helper in the well-known photographic agency, Dephot. It was here that he developed a keen interest in photojournalism. His first important assignment, in 1932, was to cover a social democratic conference in Copenhagen, addressed by Leon Trotsky--whom Capa greatly admired.

With the outbreak of the revolution and civil war in Spain in 1936, Capa's anti-fascist and socialist leanings led him to the centre of that struggle. He wanted to inform the world through his images and gather support for the Spanish fight against fascism. Like many other intellectuals of his time, Capa felt that if fascism were stopped in Spain it would be stopped everywhere else and a Second World War could be avoided. He often travelled and met with Ernest Hemmingway and others.

Capa's pioneering photographs had a major impact internationally. Nobody had seen anything like them before. Previous war photographs were static and, of necessity, taken from a distance--early cameras being heavy and cumbersome. Spontaneous photographs and close-ups were impossible, without the photographer being able to manoeuvre himself out of dangerous situations. Capa's 35mm Leica was both discreet and allowed him maximum mobility. With it he threw himself into the turmoil of war in a way nobody had done before.

The exhibition at the Queen Sofia's Museum is set up in one long room, with a divider in the middle. It proved to be too small for the number of visitors it attracted. The exhibition is divided into three distinctive phases, 1936, 1937 and 1938/39. The moods of these years are expressively reflected in Capa's photographs, changing from euphoria, to suffering, to defeat and despair.

The photographs are interspersed with contemporary pieces of writing and poems, also reflecting these shifts.

"When every Spaniard can not only read, which in itself is enough, but yearn for reading, for joy and for a good time, yes, have a good time reading, there will be a new Spain." (Republican woman)

"There is no security for anybody in any part of this war. The women stay behind, but death, the ingenious death that comes from the sky, finds them." (Robert Capa)

"I feel trapped in a Madrid turned into an island, alone, in a sky made of asphalt, criss-crossed by crows looking for children and the old. Black evening; rain, rain, tramways and militiamen." (Jose Moreno Villa)

" ... the most atrocious experience of my life was to watch, at the end of the war, a people wasted, hungry and abandoned by the rest of the world, but fighting with great courage until the last moment." (Henry Buckley)

The first group of exhibits, from 1936, begins with pictures of ordinary people in the streets: children in fairs, Easter processions, shining boots, men wearing militia berets. Militiawomen reading, preparing to go to the front, joking and laughing with militiamen, parting from their loved ones leaving for the front on trains; soldiers kissing their children good bye. All of them are full of enthusiastic optimism, happiness and confidence in their ability to win, with their fists closed in salute, singing.

This group is followed by pictures of militiamen training peasants, POUM militias reading, writing letters to their loved ones, giving speeches at the front, playing chess, repairing battered cars, studying maps, carrying their wounded or taking down the names of the dying. There are also countless pictures of the fighting itself, as it was taking place in different parts of the country. Capa spent several days with the militias and the International Brigades. Some of the pictures are so close and real you can nearly smell the gunpowder. They must have been taken at a great risk to his life.

The period of 1937 begins with pictures of the system of trenches, tunnels and caves built by the republicans in Madrid, followed by images of the ravages of the fascist bombings of the population of Madrid: destroyed streets, buildings, houses, bedrooms, wreckage, rubble. Children playing outside buildings full of grenade holes, people sleeping in the underground platforms, next to their few saved belongings or running away to escape the bombs, looking at the sky for Franco's German-built planes. Some show people putting out the fires and trying to save some of their belongings. Then come pictures of children and old people huddled over piles of clothes, with their heads and feet bandaged.

Two of the most harrowing pictures of this period are that of a mother running and pulling her daughter to safety. Both look at the sky as they run. In the hurry and confusion, the little girl has buttoned up her coat wrongly. Another image is of a soldier caught up in the branches of a tree. He was killed as he was laying a telephone line.

Many of Capa's photographs are of people's faces, those of the soldiers and militiamen bearing the cold, tiredness and boredom at the front, as well as those of civilians distorted by fear, suffering and loss.

The saddest images are in the group belonging to end of 1938 and 1939 and are concentrated on the fall of Barcelona and the flight of refugees into exile in France. Many are of people entering refugee centres, some show children walking and carrying heavy loads on their heads, or being pushed onto carts by their parents. Others are of people on the road from Tarragona to Barcelona, many of whom were bombed and killed by Franco's planes as they fled.

Then follow photos of long lines of people marching towards exile on the road from Barcelona to France, trying to reach the frontier, which was kept closed to them for some time by the French government. Capa spent several days in Figueras, the last Spanish town before the border, photographing refugees in the city, and on the access roads. On January 28 Capa left Spain forever, together with the first of the 400,000 men, women and children who eventually crossed the border.

In February 1939, while in London, Capa heard that the French government, which had so far only admitted Spanish civilians, had finally decided to admit 200,000 retreating republican soldiers, with the proviso that they must remain in reception centres in Perpignan. He was given the assignment of reporting on the conditions in these camps.

Capa travelled in March to Argelès-sur-Mer beach, a concentration camp surrounded by the sea on one side and barbed wire on the other. There, 75,000 republican soldiers were kept in isolation from even their closest relatives, living in subhuman conditions in makeshift tents and barracks with no running water, doctors or sanitation. Many wounded had to have their arms and legs amputated by their own comrades. Capa captures the conditions of these soldiers in such a moving way that many viewing the exhibition were reduced to tears.

This is a true record of a people's war. However, everything in the publicity for the exhibition presents this record of struggle as something remote and inexplicable, that should not be forgotten, but which can never return to a modern unified Spain. Capa's ability to capture the enthusiasm, energy, courage, initiative and hope of the anti-fascist forces speaks to the contrary. The hundreds of young people who filed past the photographs, eager to know more about their past, so carefully hidden by the falsifiers of history behind the so-called "peaceful transition" from fascism to democracy, were visibly moved by Capa's images. But they will only be able to understand and overcome that defeat by studying the central political lessons of the Spanish events, and by learning how the courageous men and women so movingly portrayed in Capa's photographs were betrayed by their leaders and delivered into the hands of Franco.