Driven by a burgeoning demand for energy, the Chinese government has made securing access to the largely untapped reserves of oil and natural gas in Central Asia a cornerstone of its economic policy for the next two decades. Beijing's plans are ambitious, costly and have major geopolitical implications as China stakes a claim in a key strategic area of the globe.

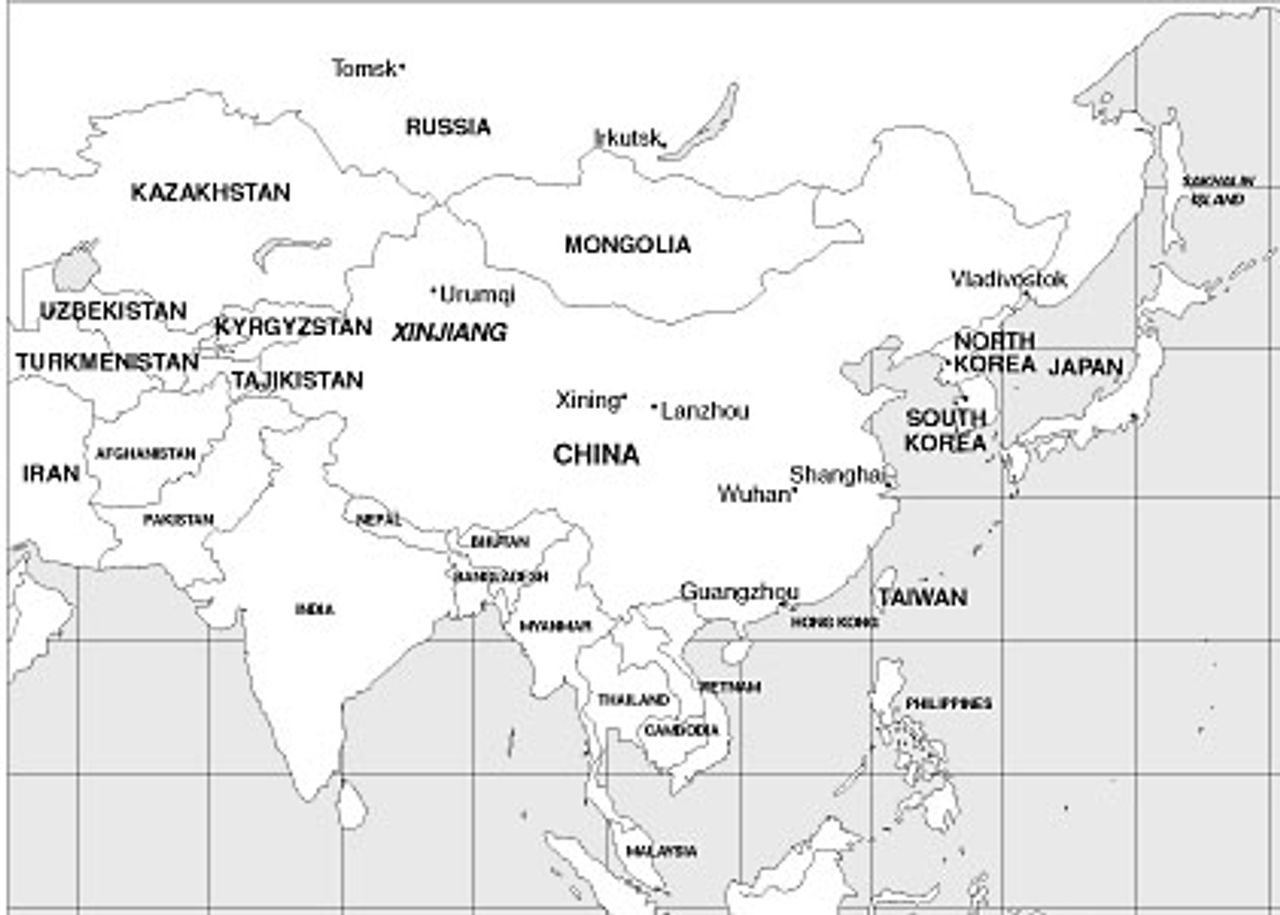

China's energy plans were unveiled at the 2000 National People's Congress. Their focus is the construction of a 4,200 kilometre network of gas and oil pipelines running from China's western province of Xinjiang to the major east coast metropolis of Shanghai.

The project's first stage is the construction of two gas pipelines from fields in Sichuan province to the central industrial city of Wuhan, then on to Shanghai by 2002. Gas fields in Shaanxi province will be linked into these pipelines. Gas and oil from basins in Qinghai province and Xinjiang province, including the major Tarim Basin, will be connected by 2005. Once completed, at an estimated cost of $US14.2 billion, the West-East energy project will enable 25 billion cubic metres of gas and 25 million tonnes of oil per year to be delivered to the industrial regions around Shanghai. As well as the pipeline network, modern refineries and power plants are being built at key points across China.

Xinjiang, which has estimated oil reserves of 20.9 billion tonnes and natural gas deposits of 10.3 trillion cubic metres, is to be developed as China's second largest oil producing region after the country's north-east. To consolidate its control, the Beijing regime is both ruthlessly suppressing a separatist movement among Xinjiang's ethnic Uiygur population—a predominantly Muslim, Turkic-speaking people—and encouraging the rapid industrialisation of the poorer western provinces of the country.

The construction of pipeline networks to China's western borders, under the control of the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and other large Chinese energy companies, also opens up the potential for China to exploit the huge energy resources of the former Soviet republics of Central Asia.

In 1997, CNPC acquired the right to develop two potentially lucrative oilfields in Kazakhstan, outbidding US and European oil corporations. In exchange for development rights, CNPC is committed to build pipelines to Xinjiang to enable the large-scale export of up to 50 million tonnes per year of Kazakh oil to China. Feasibility studies are also underway for the construction of over 3,000 kilometres of gas pipeline from Turkmenistan to Xinjiang.

Theoretically, oil and gas pipelines to China from Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan could be extended to link into the pipeline networks of both Russia and Iran. This model has been dubbed the “Pan Asian Global Energy Bridge”—a Eurasian network of pipelines linking energy resources in the Middle East, Central Asia and Russia through to China's Pacific Coast.

Growing foreign investment in China's energy sector

Underlying the pipeline project and the long-term orientation toward Central Asian oil and gas is China's exponential rise in energy consumption. Despite being the world's fifth largest oil producer, economic growth had transformed China into a net oil importing country by 1993. In the first 11 months of 2000, China imported 65.5 million tonnes of oil, mainly from the Middle East, which represents a 97 percent increase on the same 11 months in 1999.

After more than doubling in size in the 1990s, China's economy is predicted to at least double again in the coming decade. As a result, imports will rise from the current 20 percent of oil consumption to over 40 percent by 2010. Industrial power consumption—70 percent of the total—has grown 10 percent this year. Household consumption is also rising between 10 to 14 percent per annum. It is conservatively estimated that the rate of urbanisation will rise from the current 30 percent to at least 40 percent of the country's 1.3 billion people. More than 520 million people will be living in densely populated cities, mainly on the east coast, requiring electricity, heating and transport.

Unable to finance the necessary infrastructure, Beijing has been compelled to open up China's previously insulated energy sector to wholesale foreign investment. Vast sums of capital are required, not only for the multi-billion dollar pipelines, but to upgrade technically backward refineries and develop distribution networks. In July, the Chinese government announced that majority foreign ownership would be permitted in various joint venture projects associated with the West-East pipeline network. China's two largest state-owned energy companies have listed subsidiaries on Wall Street in an effort to raise billions of dollars for expansion and restructuring.

To make themselves attractive to foreign investors, the Chinese oil companies have implemented large-scale job cuts and divested non-core assets such as schools and hospitals previously provided for their employees. The first to list, CNPC, under the name of PetroChina, has eliminated an estimated 158,000 jobs. In October, China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation or Sinopec was listed. The initial public offering of the third major Chinese oil company, China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), is scheduled for early 2001.

Major international oil companies are aggressively pursuing a stake in the Chinese energy market, now the largest outside the US. Over the past 12 months, there has been a rush of strategic investments and joint venture announcements.

In early August, British-based BP Amoco purchased 2.2 percent of PetroChina in exchange for a joint venture to market petroleum and natural gas in China's coastal provinces and involvement in the West-East pipeline. In partnership with PetroChina, BP Amoco intends to develop a branded chain of at least 1,000 service stations in southern China over the next 5 to 7 years and construct a major LNG (liquid natural gas) terminal and refinery in Shanghai.

In the longer term, BP Amoco is pushing for the construction of a 2,400 kilometre gas pipeline to supply northern China from its Kovitkinskoye field near Irkutsk in Russia.

In October, US-based ExxonMobil purchased 19 percent of Sinopec's initial public offering and the two companies are developing 500 joint-branded service stations in Guangdong province, China's major export region. Along with Japanese and Saudi interests, ExxonMobil and Sinopec are constructing new state-of-the-art petroleum product refineries in Guangdong and Fujian provinces.

ExxonMobil is one of the largest foreign players in developing Central Asian and Far Eastern resources. It has major oil interests in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, and gas interests in Turkmenistan and on Russia's Sakhalin Island to the north of Japan. In cooperation with CNPC, it is studying the possibility of piping gas from its fields in eastern Turkmenistan to China.

The strategic implications

China's pipeline network has the potential to bring about a significant strategic realignment in the region. Central Asia with its huge reserves of oil, gas and minerals and strategic position is already a key arena of sharp rivalry between the US, Europe and Japan. All of the major powers, along with transnational corporations, have been seeking alliances, concessions and possible pipeline routes in the Central Asia republics.

Mutual self-interest has brought China and Russia together in the “Shanghai Five” group of nations, along with the Central Asian states of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Through the grouping, China has sought to align Russia economically and politically toward China and north-east Asia, while Russia has sought to preserve its traditional influence in Central Asia. The South China Morning Post commented after the last summit of the group in July: “If anything is going to bring the two countries and their two economies closer, it is Russian exports of its vast oil and gas wealth”.

More than economic considerations are at work though. Particularly since the NATO war on Yugoslavia and the subsequent occupation of Kosovo, a feature of Sino-Russian relations is fear that their own separatist strife—as in Chechnya or Xinjiang—will be exploited by the United States to intervene in the region. Both China and Russia are also bitterly opposed to the development of an American missile defense system that would nullify their nuclear deterrent against US aggression. Consequently, the two states are seeking to counter US influence in Central Asia and develop their relations with other key regional players such as Iran.

Among the most recent developments, Russia has secured a contract with Turkmenistan to purchase 30 billion cubic metres of gas each year. This further undermines the trouble-plagued US-backed TransCaspian Gas Pipeline—a pipeline for Turkmen gas across the Caspian Sea and out to Turkey.

No alliance has been cemented between Russia and China, but such a partnership could dramatically alter relations in Central and East Asia. It would create the necessary political framework for large-scale investment to flow into a web of pipelines crossing Central Asia and Russian Siberia to China's Pacific coast. Within 10 years, China could emerge as a major distribution hub for oil and gas exports to South Korea and Japan, two of the largest energy importing states in the world.

During November, China's premier Zhu Rongji visited South Korea to launch the “Remake West China-Korean Committee,” a body aimed at encouraging South Korean investment in the pipeline project. The thaw in tensions on the Korean peninsula and the moves to reopen the border between North and South for commerce has heightened Korean interest in Central Asian energy. Korea Gas Corporation has already joined a feasibility study examining a possible extension of the proposed gas pipeline from BP Amoco's Kovitkinskoye field in Russia to northern China by a further 1,600 kilometres through the North to South Korea.

China has made no secret of its desire for massive injections of Japanese investment into the projects. Japanese capitalism has important commercial and strategic interests in developing secure continental access to Middle Eastern and Central Asian oil and gas as an alternative to potentially vulnerable sea routes from the Middle East.

A study on China's energy plans by the US think tank, the Brookings Institute, has already warned about the potential for a strategic realignment between Japan and China to the detriment of the US. Sergei Troush wrote: “One possible tendency might be growing economic and security cooperation between China, Japan, and Korea... The decreasing importance of the sea-routes in the Indian and Pacific Oceans could see the eventual reshaping of the basic security arrangement between United States and Japan.”

Lacking any reserves of its own, the ruling class in Japan has always been acutely sensitive to the issue of oil. Its 1931 invasion of China's north-eastern Manchurian provinces was in part aimed at establishing control over oil resources. In 1941, its attack on Pearl Harbour and subsequent invasion of South East Asia was in response to a US naval blockade that closed the sea lanes through the Strait of Malacca and cut off Japan's oil supply from the Middle East and Indonesia.

Japan's dependency upon tanker-transported energy through the sea lanes of South East Asia, and therefore its vulnerability to blockade, is even more pronounced today than before World War II. At the same time, Japanese corporations and banks are also just as attracted by the prospect of superprofits from the exploitation of Central Asian resources as the major US and European-based transnationals.

Troush referred to the comments of Ikuro Sugawara, an analyst for the Japan National Oil Corporation, who wrote: “The new Asian players, including countries such as India and China, will compete fiercely for stable oil supplies and may insist on views different from those shared by United States and Japan. Japan, which is an integral part of the Asian market and is as dependent as its neighbours on the Middle East for oil, will not be able to follow the US line as closely as it has in the past.”

The exact outcome of the present manoeuvres in Central Asia and its impact on the strategic equation in North East Asia is not clear. But the international reaction to China's energy plans underscores the central importance of the region and the potential for sharp conflicts.

From the outset, the WSWS exposed the lies of the Bush administration that its illegal invasion was an act of self-defense in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11.