This is the second in a series of articles on the 2007 Sydney Film Festival, held June 8-24. Part 1 appeared on July 4.

Among the Asian movies screened at this year’s festival were three—Opera Jawa, I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone and Syndromes and Centuries—commissioned by “New Crowned Hope,” a project established last year by American theatre director Peter Sellars to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth. Sellars told the recent San Francisco Film Festival that the movies were designed to generate an artistic vision.

With the exception of some strikingly exotic moments in Opera Jawa, the three Asian films were either lightweight or somewhat disappointing.

Opera Jawa, written and directed by Garin Nugroho and the best of three movies, is a sumptuous and visually innovative musical, loosely based on a section of the Sanscrit epic Ramayana.

Nugroho takes a chapter from the ancient story—about the seduction of Sita, King Rama’s wife—modernises it and provides a new setting. In Opera Jawa King Rama becomes Setio, a poor Indonesian village potter, and Sita, from the ancient story, is Siti, a former dancer but now married to Setio.

Siti (Artika Sari Devi) and Setio (Martinus Miroto) live in a small Javanese village. They are barely able to survive by selling their earthenware pottery. Setio, who travels to other villages to sell his work, becomes jealous, begins to doubt his wife’s fidelity and then stops sleeping with her. Ludiro (Eko Supriyanto), the local butcher and one of the richest men in the area, then abducts Siti and tries to seduce her. (In the ancient epic, Ludiro is Ravana—King Rama’s rival). Thus unfolds a complex morality tale of love, jealousy, superstition and violence.

Nugroho and musical director Rahayu Supanggah mobilise an extraordinary range of artistic disciplines for the two-hour movie. They include contemporary and traditional dance, installation art, puppet theatre, gamelan percussion and other Javanese folk music, and even a form of popular Indonesian blues.

Opera Jawa has many magical, otherworldly moments, but the tale is overloaded and unnecessarily difficult to follow. There are peasant uprisings, natural disasters and a gory act of vengeance in the final scene. Nor do the various artistic genres always mesh successfully.

Opera Jawa is not the first time Nugroho has employed traditional poetry and music in his work. His movie, The Poet (2000), which is set during the 1965 Indonesia coup and was the first independent movie about the bloody military repression, uses a combination of Acehnese music, poetry and song. Set in two adjoining prison cells, The Poet is a simple, but much more emotionally engaging work than Opera Jawa.

Forty-six-year-old Nugroho is clearly a talented filmmaker and one constantly searching for new artistic forms. Opera Jawa, however, would have been much more emotionally engaging if the director had applied the “less is more” principle.

Wearing and clichéd

In contrast to Nugroho’s movie, I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone, Tsai Ming-liang’s contribution and his eighth full-length feature, is an unconvincing and tedious work.

Like many contemporary Taiwanese filmmakers, Tsai is treading water. Some of his early films—Rebels of the Neon God, Vive L’amour and The River—made during the 1990s, were intelligent and mirrored the brief renaissance of serious cinema in Taiwan at that time. Unfortunately, the writer/director has produced little of note since.

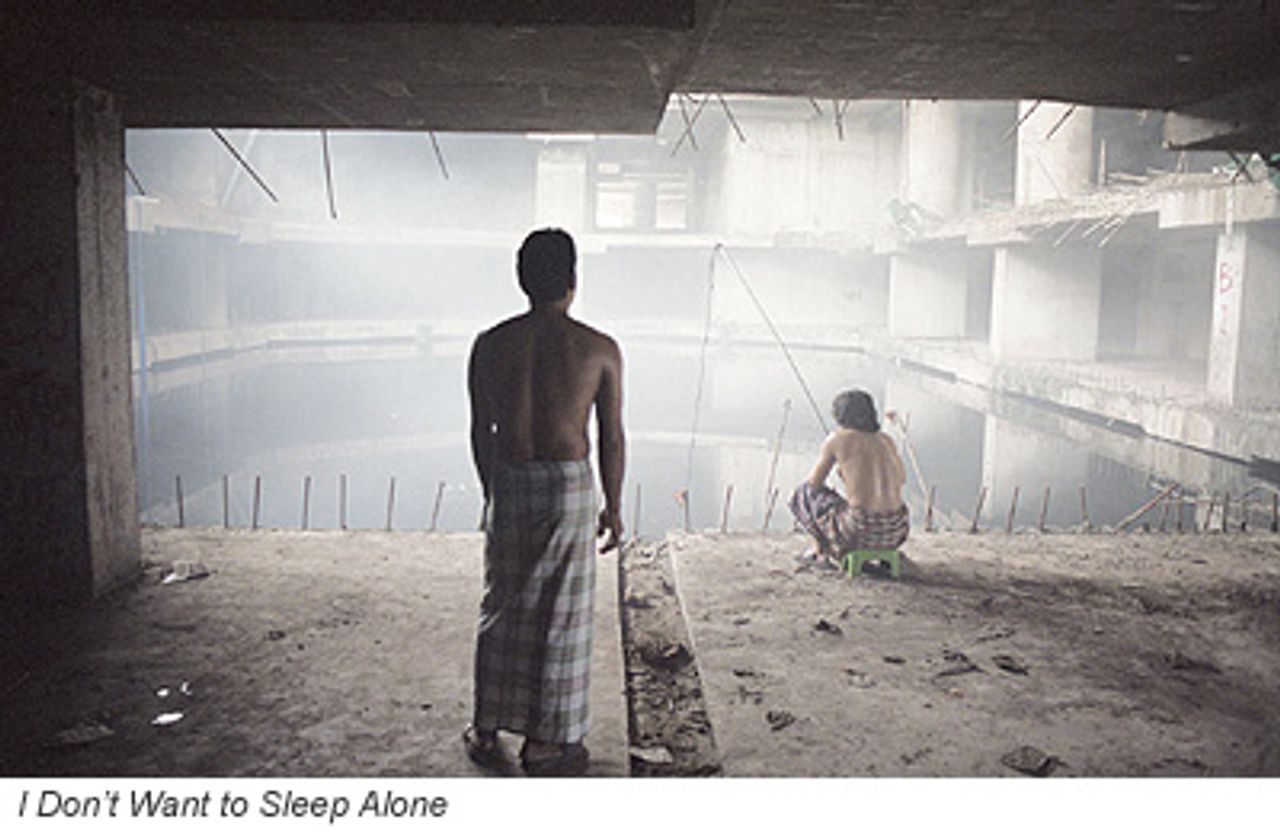

Set in Malaysia, where Tsai was born, I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone, recreates a few weeks in the life of a young homeless man. The man is robbed and severely beaten by a group of street hustlers. Left for dead outside a Kuala Lumpur construction site, he is saved by a young building worker, who brings him home and nurses him back to health.

A parallel story unfolds about a young girl (Chen Shiang-Chyi), who works in a coffee shop and is a carer for a young man in a coma. She lives a poverty-stricken life, sleeping rough at the home of the mother of the comatose man. The paralysed young man and the homeless youth are both played by Lee Kang-Sheng, who stars in all Tsai’s movies.

Much of the action occurs at night and on deserted high-rise building sites, projects probably abandoned after the 1997-98 Asian economic crisis. As the film progresses, the city becomes filled with thick smoke, with city residents forced to wear masks.

The homeless youth, who has no name and is mainly expressionless throughout the movie, becomes sexually involved with the construction worker and later the young girl. There are some nasty conflicts between the mother and the young girl, who is treated like a slave, and a jealous and violent altercation between the construction worker and the homeless youth.

The film concludes with the four main characters on a building site. The cruel mother gets her comeuppance, but there is a personal and sexual reconciliation between all the other characters. The movie ends with the three sleeping in a hopeful embrace, floating on an old mattress in an abandoned swimming pool in the smoke-filled building.

Tsai is no doubt concerned about the plight of society’s most oppressed layers and the breakdown of genuinely humane personal relationships. But the movie’s conclusion, which suggests that love alone can overcome all odds—is false and unconvincing.

Stylistically, I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone is little different from Tsai’s earlier movies. In fact, the director’s work is becoming increasingly mannered and empty. The film’s extended takes, which record the mundane details of life and the generally passionless sexual encounters, are wearing. Likewise, Tsai’s recurring shots of running taps or smoke and fog, which were interesting symbolic devices in his early work, are now just clichés.

While there is no recipe book that Tsai can use to circumvent the present artistic impasse, a more socially and historically conscious approach towards character and story development would be a good start. Up to date, Tsai has avoided this challenge.

Banned by Thai authorities

By contrast Syndromes and Centuries (Saeng Satawat), by Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, is less pretentious and, despite its somewhat cryptic character, a more interesting work. Categorised in various places as a “pre-love story”, the film is an exploration of memory and love, and a tribute to the director’s doctor parents.

Describing Weerasethakul’s enigmatic and, at times, whimsical film is difficult. The movie has no clear narrative structure and is divided into two repeating sections: the first set in a medical clinic in rural Thailand, the second in an urban hospital.

In the first section, a young female doctor interviews a slightly older medic who wants a job at the clinic. She asks several questions, supposedly to help assess whether the applicant is suitable for the job. “Do you prefer squares, circles, or triangles?” she asks and later, “What do the initials DDT stand for?” He doesn’t know, but after a few moments blandly answers: “Destroy dirty things”.

A male admirer of the young female doctor asks her to marry him. They lunch together and she tells him a story about her former relationship with an orchard farmer. Her story, however, is not completed.

An old Buddhist monk comes for a medical check up. He tells the doctor that he is having nightmares about chickens and wonders whether he is going crazy. A dentist, who moonlights as a nightclub singer, attends to a younger monk’s teeth. He sings to the younger man in the dentist chair, and then gives him a guitar.

These events are loosely repeated and/or supplemented with additional scenes in the second part of the movie, which takes place in a large urban hospital. This time, however, they appear to be remembered or re-imagined by another person—perhaps Weerasethakul’s father.

There are empty hospital corridors and the singing dentist performs to a live audience. Two middle-aged female doctors drink whisky in the hospital—one of the women explaining she needs a drink before she appears on public television. A doctor and her boyfriend exchange a passionate kiss somewhere in the hospital locker room and the movie concludes with an extended shot of a tube removing smoke from a hospital operating theatre, before cutting to footage of city residents doing aerobics in a park.

These odd scenes make little sense in isolation. But taken together, they create a light, dreamlike atmosphere of half recalled memories and thoughts.

Explaining his approach, Weerasethakul told one journalist: “The mind doesn’t work like a camera. The pleasure for me is not in remembering exactly but in the feeling of the memory—and in blending that with the present.”

To the extent that Syndromes and Centuries remains within these parameters it constitutes an interesting but lightweight experiment. Cinema, however, is clearly capable of much, much more.

Notwithstanding the harmless nature of Weerasethakul’s work, Thailand’s censorship board banned the movie last April, claiming it denigrated Buddhism and the medical fraternity.

Censors demanded the filmmaker eliminate scenes of a young monk strumming a guitar, two monks playing with a battery-operated flying saucer toy, doctors drinking whisky and the kiss scene in the hospital locker room. When Weerasethakul refused, the board banned the film and refused to return it to the director’s production company.

A press release issued by Weerasethakul, who is the first Thai director to have won international praise for his work, declared: “I, as a filmmaker, treat my works as I do my own sons or daughters. I don’t care if people are fond of them or despise them, as long as I created them with my best intentions and efforts. If these offspring of mine cannot live in their own country for whatever reason, let them be free. There is no reason to mutilate them in fear of the system. Otherwise there is no reason for one to continue making art.” The banning of Syndromes and Centuries is yet another example of the repressive conditions facing artists and filmmakers in Thailand and throughout the region, and it calls for filmmakers and artists internationally to speak out against this assault on democratic rights.

Sydney Film Festival organisers chose to remain silent about this blatant attack, failing to inform their audiences, either in pre-publicity or before any screenings, that Weerasethakul’s movie had been banned. Their indifference is unacceptable.