This is the fourth in a series of articles on the recent Vancouver International Film Festival (September 25-October 10).

"Forgive me for my life," says a man standing before an audience of angry Ecuadorians, one of whom shouts back, "We are not an American colony." The contrite speaker is John Perkins on a recent trip back to the country he had visited in the late 1960s.

Perkins is the author of Confessions of an Economic Hitman (2004) and The Secret History of the American Empire (2007). He and his first book are the subject of a documentary by Greek director Stelios Koiloglou, entitled Apology of an Economic Hitman.

Perkins is the author of Confessions of an Economic Hitman (2004) and The Secret History of the American Empire (2007). He and his first book are the subject of a documentary by Greek director Stelios Koiloglou, entitled Apology of an Economic Hitman.

Shortly after graduating from business school at Boston University, Perkins was recruited to the US government's National Security Agency (NSA)—"the nation's largest and perhaps most secretive spy organization," according to Perkins. From 1971 to 1981, he was employed as an economist by Chas. T. Main, a private consulting firm that covertly worked for the NSA.

The role of an economic hitman, Perkins explains, is to identify a Third World country—in his case, Indonesia, Panama and Saudi Arabia—"that has resources our corporations covet, such as oil." The operative then arranges massive loans from the World Bank funneled to US corporations for infrastructure projects. The loans and projects benefit "a few very rich people, but do not reach the poor at all...But they and the whole country are left holding this huge debt" that can't possibly be repaid.

The economic hitman then extorts concessions, such as cheap oil, from the hard-pressed countries. ("If you don't play our games, if you follow your campaign promises, you may go the way of [Salvador] Allende in Chile or [Jacobo] Arbenz in Guatemala or [Patrice] Lumumba in Congo.") The economic hitman is the first tool of empire, asserts Perkins.

If the economic hitmen fail to convince, then the real hitmen, "the jackals," (the Pentagon, the CIA and their contractors) are activated. Coups and assassinations are the next step, and if necessary, the military is unleashed.

One of Perkins's stated goals is to counter the Bush administration's claim that the September 11, 2001 attacks expressed some irrational hatred of American "democracy" and "freedom." Instead, he views the terrorist attacks as a form of "blowback," a backlash against US foreign policy.

He hopes his two books and the documentary expose some myths and are perhaps a safeguard against government reprisals for his whistle-blowing.

In the film, Perkins speaks pointedly about American operations against Jaime Roldós, President of Ecuador from 1979 to 1981 and Omar Torrijos, a dictator who ruled Panama from 1968 to 1981. Roldós conflicted with the US over control of the country's oil and Torrijos over control of the Panama Canal. Both died in mysterious plane crashes within three months of each other in 1981. Perkins asserts that Washington assassinated both men.

Antonia Juhasz, author of the Bush Agenda, amplifies Perkins' description of the US intervention in Iraq. "When Bechtel tried to get [Saddam] Hussein to agree to let them build a pipeline...Hussein said ‘no.'" Perkins adds, "so we sent in the jackals." After the failure of a 1995 CIA assassination attempt, the military option was set in motion. Juhasz claims that Paul Wolfowitz, former US Deputy of Defense and President of the World Bank, "spent the majority of his adult life trying to unseat Hussein."

Perkins argues that economic hitmen view Saudi Arabia as their greatest achievement: the House of Saud is propped up in return for cheap oil—and the Saudi connection to 9/11 is not pursued. When the movie opens in Ecuador, Perkins is returning to apologize for his past crimes as part of his desire "to devote the rest of my life to make this a better world."

Apology of an Economic Hitman is effective, even though its disclosures are not fundamentally new ones. Much is fleshed out and Perkins seems sincere and motivated. Although the film-noirish dramatic re-enactments are a bit corny, the insertion of advertisements boasting about the global reach of American capitalism—a vintage Ford commercial, in particular—make the point. Elsewhere in interviews, Perkins has espoused the liberal notion that the "corporatocracy" can be reined in. That being said, Perkins and Koiloglou shed light on some of the mechanisms by which American neo-colonialism operates.

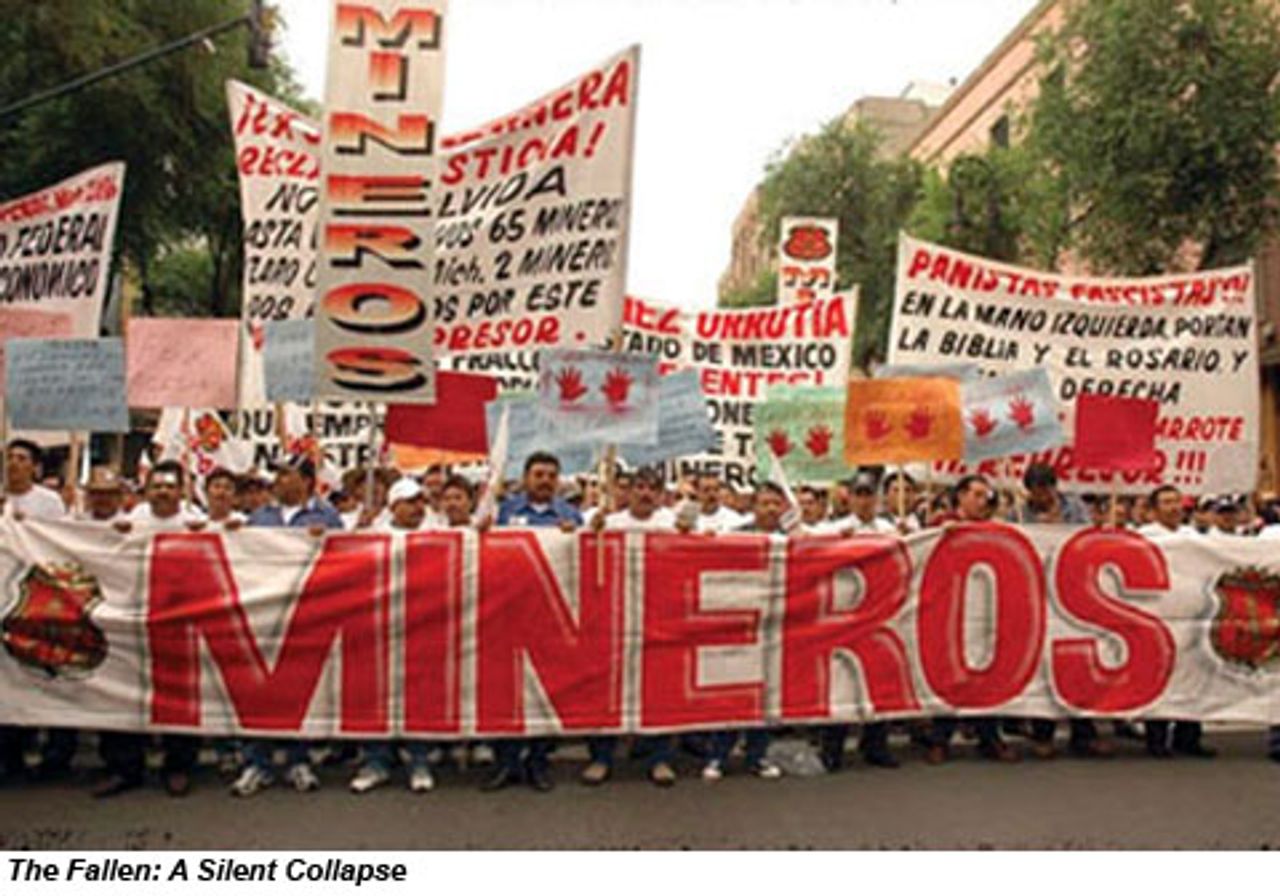

Los Caídos: Un Derrumbe silencioso (The Fallen: A Silent Collapse) is a documentary by Rudy Joffroy, which details the mining disaster and subsequent conflict that took place in Mexico in 2006. On February 19, 2006, an explosion at Grupo México's Pasta de Conchos mine, in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila, killed 65 coal miners, members of the National Union of Mine and Metal Workers (SNTMM).

Los Caídos: Un Derrumbe silencioso (The Fallen: A Silent Collapse) is a documentary by Rudy Joffroy, which details the mining disaster and subsequent conflict that took place in Mexico in 2006. On February 19, 2006, an explosion at Grupo México's Pasta de Conchos mine, in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila, killed 65 coal miners, members of the National Union of Mine and Metal Workers (SNTMM).

Union president Napoleón Gómez Urrutia called the explosion an "industrial homicide." Urrutia, a longtime SNTMM leader connected to the former ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), initiated a strike of his union's 260,000 members after he was removed from the union officialdom by the government of Vincente Fox in the wake of the explosion. Urrutia, who eventually took refuge in Canada, denied the government's charge that he had embezzled union funds. He was supplanted by former union official Elías Morales.

On April 20, 2006, two young metalworkers were killed and 30 injured following an armed assault by Mexican security forces during a strike at the Sicartsa steel mill in the southwestern state of Michoacan. The workers, also represented by SNTMM, were part of the strike called to demand Urrutia's reinstatement.

The documentary shows extensive footage of the events and the angry response of the families and communities. An examination of the causes of the mine disaster makes mention of the stunning levels of exploitation of the Mexican working class by the hugely profitable conglomerates. The Fallen however, uncritically provides a platform for Urrutia.

Chronicled in the film is the opposition of SNTMM members to the government's patently undemocratic ousting of Urrutia. Joffroy omits the fact that Urrutia, a multimillionaire economist, and the SNTMM bureaucracy collaborated in the privatization of Mexico's coal and copper mines in the 1980s and the steel industry in the 1990s, thus abetting a super increase in the exploitation of their own members. In fact, Urrutia, no less than Fox-appointee Morales, represents the corporatism of the union bureaucracy complicit in covering up Grupo México's abysmal safety record before the explosion.

Further, Leo Gerard, International President of the United Steelworkers (USW)—a right-wing, corporatist union bureaucrat—is showcased in the film. In The Fallen, Gerard delivers a toothless condemnation of Fox's action against Urrutia. The USW's web site features Gerard's press release in the wake of the mine disaster, which pathetically offers the prayers of his 350,000-member organization "to all the miners and their families."

Three generations of disparate Chinese dissidents discuss their views in director Huang Wenhai's documentary Wo men (We). Many are activists who call themselves "creatures of politics." Some live underground, sponsoring web sites that generally get shut down by the authorities. Others have been arrested multiple times. What the film shows are isolated individuals who see themselves as "grains of salt" in the face of a repressive apparatus—"a one-party dictatorship since 1949." Not surprisingly, they evince confusion about China's history and its current state of affairs.

Three generations of disparate Chinese dissidents discuss their views in director Huang Wenhai's documentary Wo men (We). Many are activists who call themselves "creatures of politics." Some live underground, sponsoring web sites that generally get shut down by the authorities. Others have been arrested multiple times. What the film shows are isolated individuals who see themselves as "grains of salt" in the face of a repressive apparatus—"a one-party dictatorship since 1949." Not surprisingly, they evince confusion about China's history and its current state of affairs.

One of them, Zhao Wei, who calls himself a "rightist," spent two decades in a labor camp where he was tortured. ("So this is what the dictatorship of the proletariat has come to!") Frustration runs high, for "at every level of government, you'll find a petty tyrant." Predicting that either people stay silent and "become slaves or take up arms and rise in rebellion," they hope that China will not be destroyed by the attendant chaos. One says in passing that some of the dissident groups are funded by the US. Even the honest elements are thoroughly cut off from a left-wing critique of the regime and remain trapped in a national framework.

The most well-known of those featured in the film is Li Rui, a one-time secretary to Mao Zedong. He was sentenced to prison after criticizing Mao's disastrous agrarian policy known as the "Great Leap Forward"—modeled after the USSR's "Third Period" of forced collectivizations. During the 1980s, he was an ally of the ousted party chief Hu Yaobang and became a leading critic of the contentious Three Gorges Dam. Interestingly, Li Rui notes in the course of the film that "the Chinese revolution was a peasant uprising." He says he supported the students in the Tiananmen protests in 1989. We is a narrow look at the widespread discontent in China.

American filmmaker Lance Hammer determined to make a film about the Mississippi Delta, one of the most impoverished rural regions in the US, after a visit to the area. He was impressed by its austere, flat "almost lunar" landscape, the sorrow of its people, their "patient endurance in the face of suffering, and the dignity of this endurance." This is the mood that pervades his debut film Ballast.

American filmmaker Lance Hammer determined to make a film about the Mississippi Delta, one of the most impoverished rural regions in the US, after a visit to the area. He was impressed by its austere, flat "almost lunar" landscape, the sorrow of its people, their "patient endurance in the face of suffering, and the dignity of this endurance." This is the mood that pervades his debut film Ballast.

The storyline is direct and the characters well-sketched. The film revolves around the impact of a suicide on the family of a convenience store owner, Darius. It is a tragedy that changes the lives of his twin brother (Micheal J. Smith, Sr.), his estranged wife Marlee (Tarra Riggs) and troubled 12-year-old son James (JimMyron Ross).

Wintry, bleak skies accent the poverty of the protagonists—played by non-professionals. The camerawork intimately captures the characters. Their thoughts and feelings and silences are registered with care.

The movie's failing lies its emphasis on the "dignity of endurance," which translates into a passive attitude towards an abandoned land and its downtrodden inhabitants. An all-too-easy outcome complements this weakness.

Crossing by South Korean director Kim Tae-Kyun is a rambling, overheated saga centering on Yong-Soo, a coal miner who lives in extreme poverty with his pregnant, tuberculosis-stricken wife and son in a small North Korean mining village. In search of medicine and food, Yong-Soo secretly crosses the border into China, but is captured and forcibly removed to South Korea. Meanwhile his wife dies and his son undertakes a fatal journey to reunite with his parent.

Crossing by South Korean director Kim Tae-Kyun is a rambling, overheated saga centering on Yong-Soo, a coal miner who lives in extreme poverty with his pregnant, tuberculosis-stricken wife and son in a small North Korean mining village. In search of medicine and food, Yong-Soo secretly crosses the border into China, but is captured and forcibly removed to South Korea. Meanwhile his wife dies and his son undertakes a fatal journey to reunite with his parent.

North Korean and Chinese social conditions are no doubt appalling. But it questionable whether South Korea is the land of milk and honey, as the film would have it. Kim hammers the viewer in a way not so different from the crudest of anti-communist propaganda movies. Added to the mix is that the filmmaker in general appears incapable of artistic subtlety.

To be continued