The ruling Labour group of Glasgow City Council has decided to press ahead with the closure of 20 primary schools and nurseries in the city.

The decision expresses the contempt with which the Labour Party, and the financial elite for whom it speaks, views the city’s working population.

The April 15 verdict, taken by a margin of 31 to six, makes much more likely that the proposed closure of nine nurseries and 11 primary schools by the end of August will be passed by the full city council on April 23.

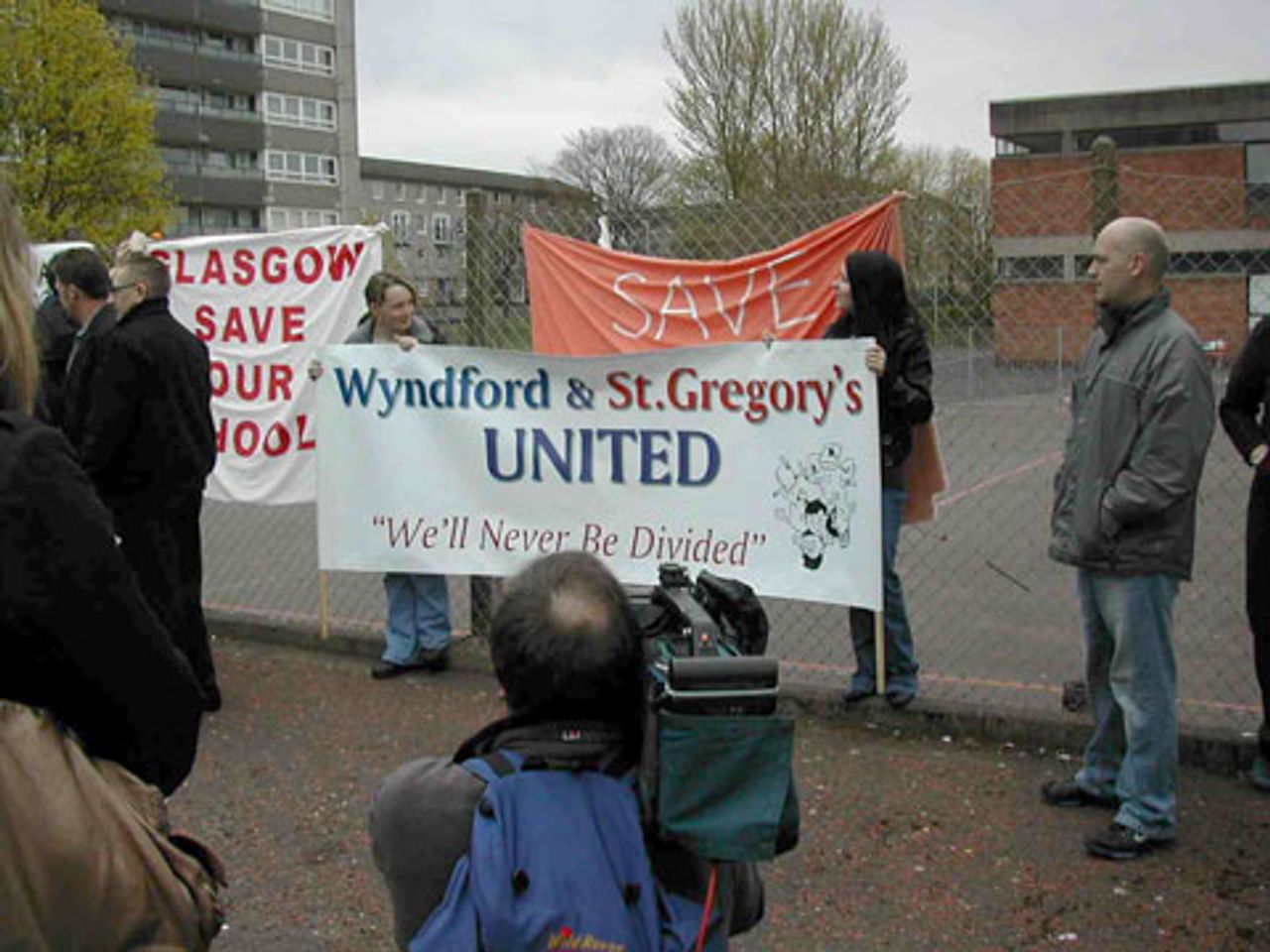

The Labour group voted to close the schools despite protests across the city including demonstrations and the occupation of two primary schools in the Maryhill area by concerned parents and their supporters. In addition, the city authorities received 7,200 responses to the closure plans, 96 percent of which opposed the move.

The issues surrounding the occupation of both Wyndford and St Gregory’s primary schools are typical. Both schools—one Catholic, one Protestant—are housed in identical and adjacent buildings in a single campus. Popular, with proven educational credentials, both have a track record of opposing the sectarian division and bullying which remains prevalent in some areas in Scotland.

Yet under the pretext of falling school rolls, the city council intends to move children from their current primaries to other schools some distance away. After closure, the abandoned school buildings will be boarded up or demolished.

Wyndford and St Gregory’s were both occupied a fortnight ago by up to 20 parents, families and supporters at the start of the Easter holidays. Parents have been sleeping in the sports halls of both schools, and have mounted a determined campaign to keep the other threatened institutions open.

Under the “Save Our Schools” umbrella group, parents across the city have mounted a series of demonstrations, events and press conferences.

Speaking for Victoria Primary and Nursery campaign, Tracey, a parent, told a press conference held April 14 outside Wyndford Primary:

“We will have 60 pre-five years places lost in the community. The media are always highlighting Govanhill as a deprived area. If you take away [the school] we will have nothing left. The children are also being split into two schools. Their friends are being left behind, depending on where you live.”

The World Socialist Web Site interviewed Claire Doris, Derek Hay and Collette James, involved in the occupation at Wyndford and St Gregory’s primaries. Claire has one child and Collette two children in the schools affected.

Collette said: “Everybody has supported us. Shops have been handing in rolls, crisps and juice in morning. The community is a lot stronger, overcoming the divide between the two faiths. The church and the chapel lit candles in the school. They did a walk up to Ruchill, and you’ve never seen that before.

“This is nothing to do with religion anymore, it’s just the schools.

“It’s been brilliant; we have had loads of support. Somebody handed in a Sunday roast. The Chinese takeaway around the corner sent food.”

Teachers have been kept as much in the dark as parents. The main teachers union, the Educational Institute for Scotland (EIS), has washed its hands of the matter. Local EIS branch secretary Willie Hart told the Glasgow Herald in January: “We have had assurances that there will be no compulsory redundancies and staff can be redeployed where necessary.”

Claire Doris explained: “We got a letter before the teachers knew. We got called to a meeting that day. Parents in St Gregory’s were phoning up to find out what was happening, and the teachers didn’t have a clue.”

Defending the April 16 Labour group’s decision, City Council leader Steven Purcell absurdly claimed to the media that the closures were in the best interests of pupils, citing falling rolls, and decayed buildings.

“When a primary school falls below 50 percent occupancy it has a drastic effect on teaching and learning.

"When these proposals are implemented, the newly merged schools will have an average of 60 percent plus occupancy, allowing us to provide more teaching, including wider access to more sport, music, art and drama.”

Purcell’s presentation of demoralised and half empty schools is clearly belied by the powerful opposition generated by the plans.

One might, in any case, think that falling school rolls presented an opportunity to reduce class sizes. However, a member of the city council’s education executive made the council’s unbridled cynicism clear.

Councillor Jonathan Findlay, executive member for education, told the Sunday Herald, “In Glasgow we are not intending to cut class sizes, not only because it would cost millions upon millions of pounds to do so, but because it is an irresponsible policy.

“Our own independent education commission has provided us with compelling evidence that cutting classes to 18 will do nothing to further the literacy and numeracy skills of our young children.”

Findlay’s statement coincided conveniently with the closure programme.

The closures timetable, as well as the token and fraudulent character of the “consultation” process, further reveals the arrogance of Glasgow’s authorities.

Less than four months was allocated, from February 2 to June, between the proposal being announced and the decisions implemented. “Decant” meetings were already timetabled for the second week in May before any final decision had supposedly been made. No alternate timetable, giving room for alternate decision to be arrived at, was published.

The council has even threatened to close Wyndford and St Gregory’s prematurely, bussing children to their replacement schools, if the occupations are not abandoned.

Council leader Purcell’s school roll figures are from the city council’s own Schools Estate Management Plan, under whose terms the school estate is to be reduced to 150 primary schools and 30 secondary schools. The plan is simply a budget trimming and rationalisation exercise out of which a mere £3 million will be saved annually, while an additional £250,000 will be required in transport costs.

Yet the council’s education budget includes an annual £6.47 million charge made for the costs of handing over much of the school estate to a public-private partnership scheme in 2000-01. At the time, many warnings were issued of the ruinous long term impact of an expensive 40-year contract, which over its life time will turn over some £1.2 billion to PPP school developer 3ED.

The education cuts are part of nearly £20 million in budget cuts proposed by the council in 2008 for the 2009-10 year, out of a total budget of £2.4 billion. The council, which has capital reserves of some £144 million, does not appear to have been impacted by the collapse of the Icelandic banks and is only running a small deficit. But the city’s annual financial statement notes the need for careful monitoring of the situation, and revenue falls are anticipated.

Nevertheless, the council, in addition to large capital projects such as a new motorway, has allocated some £3.42 million to the department responsible for promoting the 2014 Commonwealth Games. Like the London Olympics in 2012, the 2014 games are viewed as a great opportunity for the city’s builders, developers and retailers to suck in large amounts of revenue.

The council’s decision to go ahead with the cuts poses the school campaigners with a dilemma. To date, their perspective has been restricted to one of embarrassing the local authority into changing its position.

But the Labour Party long ago made clear it is inured to moral pressure, or being shamed and exposed as a right-wing cabal of financiers, trade union bureaucrats and aspiring local entrepreneurs. Moreover, although the Glasgow cuts are not directly related to the world financial meltdown, the shadow of financial crisis hangs over all current events.

The amount required to keep all 25 Glasgow schools open amounts to a smallish pension pot for one of the UK’s ruinous banking CEOs. Fred Goodwin of Royal Bank of Scotland was awarded a £25 million pot for his role in events leading up to the British government bailing out the bank to the tune, so far, of £24 billion. The entire British local and national education budget is currently £80 billion, an amount dwarfed by the potential debt liabilities of RBS alone.

To stand any prospect of reversing the schools closures a far wider campaign is necessary. This must seek the broadest political mobilisation of working people in defence of education, jobs and living standards, and must seek real and permanent encroachments into the private and corporate wealth and social position of the financial elite.