We are posting here the third part of a four-part series on the 1934 Minneapolis general truck drivers’ strike. Part one was posted on August 26. Part two was posted on August 27.

The strike of July-August

On July 5, a massive parade and rally was staged by the union to prepare workers for the coming struggle. AFL leaders and FLP office holders were also invited and put on record as supporting the next strike.

The May events had swung wide sections of the population behind Local 574. One aspect of this would lead to a considerable inflow of intelligence bearing on the activities of the Citizens Alliance and the employers. Secretaries listened in on their bosses’ phone calls and created carbon copies of critical letters or communications. Janitors retrieved letters from wastebaskets. All of this was forwarded to strike headquarters for analysis.

Local 574 cruising pickets stop a driver to check for permits.

Local 574 cruising pickets stop a driver to check for permits.During the May strike, some problems had flared up between pickets and individual farmers who attempted to bring their produce into the city. The union rectified this by getting farm groups such as the National Farm Holiday Association to organize and staff pickets on the main roads entering the city. Only farmers who were members of farm organizations would be allowed to enter the city, and a special farmers’ market was set up outside the market district to allow them to sell their produce. The membership rolls of the farm organizations began to swell and dues were paid up.

The most important addition to the union cause was the daily strike paper, The Organizer, which combated the lies of the Citizens Alliance and capitalist press and the treachery of the mediators, the labor bureaucracy and the Farmer-Labor government, and focused the workers’ movement on its most critical tasks. Cannon considered it the “crowning achievement” of the strike. “Without The Organizer the strike would not have been won,” he wrote. [22]

The Citizens Alliance also prepared. Charles Rumford Walker wrote: “Chief of Police Johannes asked for a nearly 100 percent increase in his police budget. The budget included the cost of 400 additional men and the maintenance of a police school.... He asked for $7,500 for the school and $33,200 for other equipment. ‘The police,’ he said, ‘must be trained just like an army to handle riots.’ Included in the budget were $1,000 worth of machine guns, 800 rifles with bayonets, 800 steel helmets, 800 riot clubs, and 26 additional motorcycles.” [23]

In May, the Citizens Alliance had focused a good deal of its propaganda against the closed shop, while the union merely demanded what the federal government had already legislated as the workers’ right—to organize and select their own representation. The tactic made the employers appear obstinate in the eyes of wide layers of the public.

The Alliance now focused much more narrowly on the communist leadership of Local 574, hoping to confuse the uninformed worker and pressure the AFL bureaucracy to undermine the struggle. In the Minneapolis Star, the CA asked, “Are the Communists insidiously taking over the union labor organizations—most of which are reputable and patriotic—to achieve the Russianizing of Americans?” [24]

Teamster International president Tobin aided the Alliance by issuing a public attack on Local 574 in the union’s magazine. “We see from the newspapers that the infamous Dunn[e] Brothers...were very prominent in the strike of Local No. 574 of Minneapolis.... All we can say to our people is to beware of these wolves in sheep clothing...the International Union will help you in every way it can...to protect our people from these serpents in human form.” [25]

An article in The Organizer, approved by the rank and file, responded:

“We note with the greatest indignation that D. J. Tobin, president of our international organization, has associated himself with this diabolical game of the bosses by publishing a slanderous attack on our leadership in the official magazine. The fact that this attack has become part of the ‘ammunition’ of the bosses in their campaign to wreck our union is enough for any intelligent worker to estimate it for what it really is. We say plainly to D. J. Tobin: ‘If you can’t act like a union man and help us, instead of helping the bosses, then at least have the decency to stand aside and let us fight our battle alone.... Our leadership and guidance has come from our own local leaders, and them alone. We put our confidence in them and will not support any attack on them under any circumstances.’ ” [26]

The Trotskyist leaders of the strike continued to hold no positions within the union. However, to counteract the threat from the conservative local Teamster officials, workers elected a “Committee of 100” of the best elements in the union. The turbulence of the coming struggle meant that rapid decisions would have to be made without the possibility of convening the full membership. The conservative executive board of the union was then incorporated into the strike committee, where it could be controlled and outvoted.

The leaders of Local 574 also faced provocations from the Stalinized Communist Party. In 1934, the CP internationally was still carrying out its ultra-left policy, known as the “Third Period.” This policy had met with its most disastrous results in Germany, where the CP leadership, under directions from Stalin, denounced the Social Democrats as “social fascists,” rejecting Trotsky’s call for the party to adopt the tactic of the united front and appeal to the Social Democratic Party and unions to join with the CP in defending workers’ organizations against Hitler and his Nazi brownshirts. The Stalinist ultra-left policy, essentially the reverse side of the opportunist coin, repelled the Social Democratic workers, left the reformist labor bureaucracy off the hook, widened divisions within the working class, and paved the way for Hitler’s assumption of power in January 1933.

In the United States, the CP called for the construction of separate “red” trade unions and opposed a political struggle to expose and remove the right-wing leadership of the AFL. In Minneapolis, it tried to set up a rival unemployed workers’ union in opposition to the one already sponsored by Local 574 and the AFL.

Some of the CP’s more bizarre tactics included disrupting the activities of Local 574 picket captains, who were trying to stop scab trucks, and instead demand that they occupy city hall. The Stalinists also issued a proclamation demanding that CP members be put on Local 574’s negotiating committee. In relation to the farmers, it declared the National Farm Holiday Association a social fascist movement.

During the May strike, the CP revealed its inability to advance correct Marxist tactics in relation to the Farmer-Labor Party and Governor Olson. It demanded that Local 574 call a general strike directly against Olson. This was at a time when Olson was verbally—not to mention financially, having personally contributed $500 to Local 574—supporting the strike. The overwhelming majority of workers harbored illusions that he would aid the struggle of Local 574. The Trotskyist leaders judged correctly that his “support” would have to be tested and exposed in the course of the struggle before workers could shed their illusions in the FLP governor.

While the workers did indeed change their evaluation of Olson in the heat of the July-August struggles, the Stalinists soon dropped their social fascist rhetoric and moved in the opposite direction. When the Kremlin inaugurated the popular front line in 1935, which called for the subordination of the working class to the liberal bourgeoisie, the CP flip-flopped and supported the FLP in Minnesota as well as Roosevelt and the Democratic Party nationally.

Police use tear gas

Police use tear gasOn July 16, a new strike was launched and cruising pickets hit the streets of Minneapolis. Strikers began the strike without the clubs they had used to conclude the May strike. It was an effort to deny the police an excuse to initiate violence or provide Governor Olson with a pretext to bring in the National Guard. Mayor Bainbridge, nevertheless, called on Olson to mobilize the Guard, and the FLP governor initiated a recall of the units and set up a provisional battalion at the Minneapolis Armory.

Mediators dispatched by the Roosevelt administration met with both sides, but the Citizens Alliance refused to sign a direct contract with the union. On the evening of July 18, the Alliance met with Police Chief Johannes and pressured him to act. A plan was hatched to launch a direct and violent attack on the union, with the hope of shattering the strike. The Minneapolis Star quoted the chief giving orders on July 19 to his assembled officers:

“We’re going to start moving goods.... Don’t take a beating.... You have shotguns and you know how to use them. When we are finished with this convoy there will be other goods to move.... Now get going and do your duty.” [27]

The union avoided that day’s provocation. But the following day, July 20, a single truck carrying a few groceries pulled out from the loading docks in the market district. Some 100 police in squad cars armed with riot guns, accompanied by another 50 police on foot, escorted the vehicle. When a truck with nine pickets moved to cut it off, police leveled their riot guns and opened fire.

Bloody Friday, July 20. Police open fire on pickets; Local 574 striker Henry Ness and unemployed worker John Belor are killed.

Bloody Friday, July 20. Police open fire on pickets; Local 574 striker Henry Ness and unemployed worker John Belor are killed.“In a matter of seconds two of the pickets lay motionless on the floor of the bullet-riddled truck. Other wounded either fell to the street, or tried to crawl out of the death trap as the shooting continued. From all quarters strikers rushed toward the truck to help them, advancing into the gunfire with the courage of lions. Many were felled by police as they stopped to pick up their injured comrades. By this time the cops had gone berserk. They were shooting in all directions, hitting most of their victims in the back as they tried to escape, and often clubbing the wounded after they fell.” [28]

In all, 50 pickets and another 17 bystanders were wounded. One Local 574 striker, Henry Ness, and an unemployed worker, John Belor, died. The Organizer denounced Johannes and the Citizens Alliance, writing: “You thought you would shoot Local 574 into oblivion. But you only succeeded in making 574 a battle cry on the lips of every self-respecting working man and working woman in Minneapolis.” [29]

That night, 15,000 workers rallied at strike headquarters. On July 23, a citywide strike of all transport workers was launched. More than a dozen members of the Minneapolis Central Council of Workers, which represented unemployed workers assigned to Roosevelt New Deal work projects, had been shot in the ambush, and all 5,000 members of the council walked off the job.

100,000 attend funeral of Local 574 martyr Henry Ness

100,000 attend funeral of Local 574 martyr Henry NessOn July 24, some 100,000 people lined the streets and took part in a mass march that accompanied Henry Ness’s body through Minneapolis. Police disappeared from the streets and strikers assumed responsibility for directing traffic.

The anger of workers as well as sections of the middle class ran thick. Calls came for the firing of the police chief and the impeachment of the mayor. Many workers came to the union headquarters armed with guns. But the strike leaders understood that to allow the arming of the workers would play into the Citizens Alliance’s hands.

The Minneapolis strike, despite nationwide popular support, still remained a largely isolated movement. To unleash civil war would provide the pretext for both Olson and Roosevelt to militarily crush the strike. The goal of the struggle continued to be union recognition and a contract. The Trotskyist leadership, in what strike leader Farrell Dobbs confessed was “the hardest thing I ever did in my life,” disarmed the workers. [30]

As the strike resumed, Police Chief Johannes used 40 squad cars with riot police to accompany slow-moving convoys of trucks. At the same time, masses of unarmed cruising pickets shadowed these convoys. While some produce was delivered, Johannes did not have the forces to provide coverage to all 166 companies.

An extremely complex situation developed. FLP Governor Olson faced fall elections and realized that his inability to end the strike could undermine his future. As one historian put it, the “strike reinforced moderates’ understanding of third-party vulnerability and the continued advantages, indeed the necessity, of working with a national Democratic administration.” [31]

Roosevelt calculated that he could use the favor of federal collaboration in ending the strike to bring the Farmer-Labor Party more securely under the wing of the Democratic Party. James Cannon later explained the attitude of the Communist League of America to Olson:

“The strike presented Floyd Olson, Farmer-Labor governor, with a hard nut to crack. We understood the contradictions he was in. He was, on the one hand, supposedly a representative of the workers; on the other hand, he was governor of a bourgeois state, afraid of public opinion and afraid of the employers. He was caught in a squeeze between his obligations to do something, or appear to do something, for the workers and his fear of letting the strike get out of bounds. Our policy was to exploit these contradictions, to demand things of him because he was labor’s governor, to take everything we could get and holler every day for more. On the other hand, we criticized and attacked him for every false move and never made the slightest concession to the theory that strikers should rely on his advice.” [32]

Meeting with Roosevelt’s mediators, Olson fashioned an agreement that called for the reinstatement of all strikers, union elections, minimum wages and arbitration to determine future wages. On the question of inside workers, the agreement limited this expanded representation to only 22 companies. The proposal was publicly announced, and Olson threatened martial law if the two sides did not agree. By threatening martial law, the governor hoped to encourage individual firms to break ranks with the Citizens Alliance and sign. Only those firms that signed on would be given military permits to move products.

Despite their opposition to arbitration and the limited representation of inside workers under the proposal, Local 574’s leaders saw in the offer a basis for securing future gains. By winning elections in those firms where inside workers had been excluded under the mediator’s proposal, they would still be able to claim the right to negotiate on their behalf. A recommendation was made to the ranks to accept the proposal and it passed overwhelmingly. The Citizens Alliance replied, “Under the circumstances we cannot deal with this communistic leadership,” and rejected the proposal. [33]

On July 26, Olson declared martial law and 4,000 guardsmen invaded downtown Minneapolis. Picketing was banned as well as open-air rallies. CLA leaders Cannon and Max Shachtman were arrested within hours, held, and then ordered out of town. They agreed to exile, but then ensconced themselves in St. Paul, where they continued to provide guidance to the strike.

National Guardsmen deployed in Minneapolis

National Guardsmen deployed in MinneapolisInitially, only small firms signed on to the mediators’ proposal, while large firms remained committed to Citizens Alliance discipline. Under intense pressure, Olson began to cave in on his original plan, and within four days more than 7,500 trucks had been given permits, including those from firms that had rejected the mediator’s proposal. Olson, in an attempt to extract an agreement from the Alliance, further backtracked on the demand that employers recognize the union.

On July 31, Local 574 held a rally that was attended by 25,000 workers. Olson was roundly denounced, and the union declared that picketing would be resumed the following day in defiance of martial law.

Vincent R. Dunne arrested August 1 during National Guard raid on Local 574 strike headquarters

Vincent R. Dunne arrested August 1 during National Guard raid on Local 574 strike headquartersAt 4 a.m. on August 1, some 1,000 National Guardsmen surrounded the union headquarters and shut it down. Vincent and Miles Dunne, along with Bill Brown and the union’s doctor, were put in a military stockade. Wounded workers in the union’s hospital were hauled off to a military institution. Olson also had the guard raid the headquarters of the AFL.

Grant Dunne and Farrell Dobbs escaped the dragnet and met with members of the Committee of 100. A decision was made to decentralize the union’s operations across the city. The leadership of the strike now fell to the lower ranks, but little was lost. The back streets of Minneapolis were enveloped in a virtual guerrilla war out of the sight of the National Guard and police.

“A series of control points was set up around the town, mainly in friendly filling stations, which cruising squads could enter and leave without attracting attention. Pay phones in the stations and couriers scouting the neighborhoods were used to report scab trucks to picket dispatchers. Cruising squads were then sent to the reported locations to do the necessary and get away in a hurry. Trucks operating with military permits were soon being put out of commission throughout the city.

National Guard protecting strikebreaker

National Guard protecting strikebreaker“Within a few hours over 500 calls for help were reported to have come into the military headquarters. Troops in squad cars responded to the calls, usually to find scabs who had been worked over, but no pickets.” [34]

An attempt by Governor Olson to pressure picket captains to enter into negotiations to settle the strike failed miserably. The pickets responded by demanding the release of their leaders. Meanwhile, The Organizer came off the press with headlines:

“Answer Military Tyranny by a General Protest Strike!—Olson and State Troops Have Shown Their Colors!—Union Men Show Yours!—Our Headquarters Have Been Raided! Our Leaders Jailed! 574 Fights On!”

National Guard raids AFL Central Labor headquarters

National Guard raids AFL Central Labor headquartersIn the May strike, the Stalinists of the Communist Party had agitated for a general strike. But the Trotskyists had avoided the demand and instead limited wider strike calls only to transport workers under their control. They understood that a general strike was not a panacea for the workers’ movement. The calling of a general strike would have allowed the AFL bureaucrats to take seats on a general strike committee, from which they would become a majority that would give its support to any settlement manufactured by Olson at the expense of the workers.

In August, however, Olson was completely discredited as a strikebreaker, and the call for a general strike ignited a movement of workers across the city on behalf of Local 574 and prevented the AFL from undermining the struggle. In the new situation, Olson was compelled to back down, release those he had arrested and return strike headquarters to union control.

On August 5, Olson revoked all military trucking permits save those for a limited number of goods. The Citizens Alliance raged and demanded that military law be suspended. The following day Olson appeared opposite the Alliance’s attorney in front of the Hennepin County District Court to decide the issue. The court backed Olson’s control of the guard and permits, declaring, “Military rule is preferable under almost any circumstances to mob rule.” [35]

After martial law, a virtual guerrilla war enveloped the back streets of Minneapolis.

After martial law, a virtual guerrilla war enveloped the back streets of Minneapolis.It is believed that behind the Citizens Alliance request for a suspension of martial law was its desire to clear the way for an escalation of indiscriminate shooting of workers in the streets. Father Francis Haas, one of Roosevelt’s mediators in the thick of the Minneapolis events, wrote to a friend, “I dread to think of the violence and bloodshed to follow.” [36]

Local 574 was faced with grave difficulties throughout August. The cost to maintain the union’s operations was $1,000 a day. Its leading ranks were exhausted, and 130 members had been arrested by the National Guard and put in the stockade.

Local Teamsters bureaucrats attempted to undermine the strike by demanding that taxi drivers and filling station attendants be detached from Local 574 and put in separate crafts. Some workers, discouraged by the arduous struggle, drifted back to work. But the union continued to receive support from the working class and it shouldered on. It was also aware of problems in the opposing camp.

On August 8, Olson left Minneapolis for a private meeting with President Roosevelt, who was visiting the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Olson appealed to Roosevelt to use the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to put pressure on the Minneapolis companies, and primarily Northwest Bancorporation.

Northwest Bancorporation “had the greatest concentration of banking resources of any region of the country outside of California.” It was the central pillar of the Alliance, using its credit to support businesses that toed the open shop line and to punish those inclined to settle with unions. But the Depression had found sections of the mighty bank’s empire unable to meet the New Deal’s requirement that its capital fund exceed 10 percent of its deposits. In 1933, the bank had been forced to get the RFC to purchase $23 million in preferred stock and capital notes to keep the bank from going under. [37]

Roosevelt’s negotiators now threatened to recall the loan as a way of bringing the Citizens Alliance into line, while trying to defuse the explosive class tensions in Minneapolis.

The strike had also added to the fiscal woes of the ruling class. The July-August strike would ultimately last 36 days and, according to author Thomas Blantz, “cost the city an estimated $50,000,000. Bank clearings during the strike were down $3,000,000 a day, approximately $5,000,000 was lost in wages and the maintenance of the National Guard had cost the taxpayers over $300,000.” [38]

The intelligence networks of Local 574 gave them an insight into the disarray within the ranks of the employers, and The Organizer pounded away:

“Various sources, including direct statements of individual employers themselves, indicate a widespread revolt during recent days in the ranks of the firms affected by the strike. The staggering financial losses incurred as a result of the strike already far exceed what the cost of the modest wage increases demanded by the union would amount to over a long period of time....

“The financial Hitlers who want to smash every labor union in town...have confronted these firms with the alternative of a ruination of their business...

“The most fatal illusion that could seize us now would be the idea that the new military orders of Governor Olson, limiting truck permits, can win the strike for us and that we can passively rely on such aid. It was Olson and his military force that started the truck movement in the first place. There is no guarantee that he will not turn about and do the same tomorrow.... There is no power upon which we can rely except the independent power of the union. Trust in that, and that only.” [39]

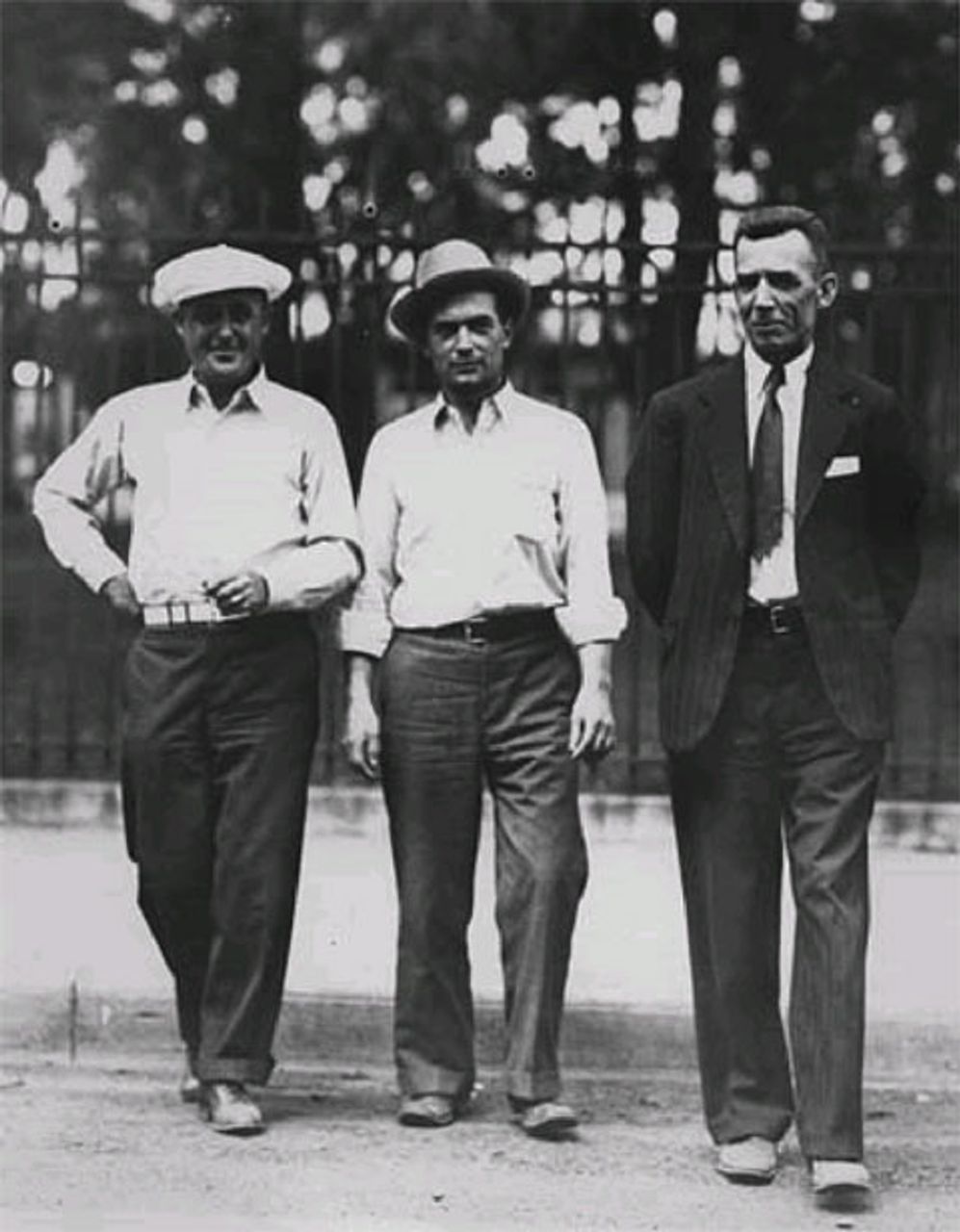

Local 574 president William Brown, Miles Dunne and Vincent R. Dunne after their release from the military stockade at the fairgrounds

Local 574 president William Brown, Miles Dunne and Vincent R. Dunne after their release from the military stockade at the fairgroundsOlson did indeed begin to backtrack on granting permits, and soon thousands of trucks were rolling, of which only one third had agreed to the mediated proposal. But on August 18, the Citizens Alliance cracked and agreed to a proposal for new mediation.

The new proposal was similar to the previous one in terms of union elections, the representation of inside workers, and a ban on victimizations. Minimum wages were set at 50 cents an hour for drivers and 40 cents an hour for other workers.

The elections resulted in Local 574 winning representation rights for 61 percent of the workers in transportation. In arbitration, wage rates were increased by 2-1/2 cents an hour for all workers. In the second year of the contract, wages were raised again by another 2-1/2 cents.

In local union elections, the conservative elements of the union were voted out and Vincent and Grant Dunne, along with Farrell Dobbs, were installed.

Notes:

22. Cannon, The History of American Trotskyism, p. 160.

23. Walker, p. 158.

24. Millikan, p. 278.

25. Dobbs, p. 112.

26. James P. Cannon, Notebook of an Agitator (Pathfinder Press, Inc., 1973), pp. 76-77.

27. Walker, p. 165.

28. Dobbs, p. 127.

29. Dobbs, pp. 129-30.

30. Dobbs, p. 137.

31. Gieske, p. 196.

32. Cannon, The History of American Trotskyism, p. 161.

33. Millikan, p. 280.

34. Dobbs, p. 154.

35. Millikan, p. 283.

36. Thomas Blantz, Father Haas and the Minneapolis Truckers’ Strike of 1934 (Minnesota History, Vol. 42, No. 1, Spring, 1970), p. 12.

37. Millikan, pp. 235, 242.

38. Blantz, p. 14.

39. Cannon, Notebook of an Agitator, pp. 81-84.