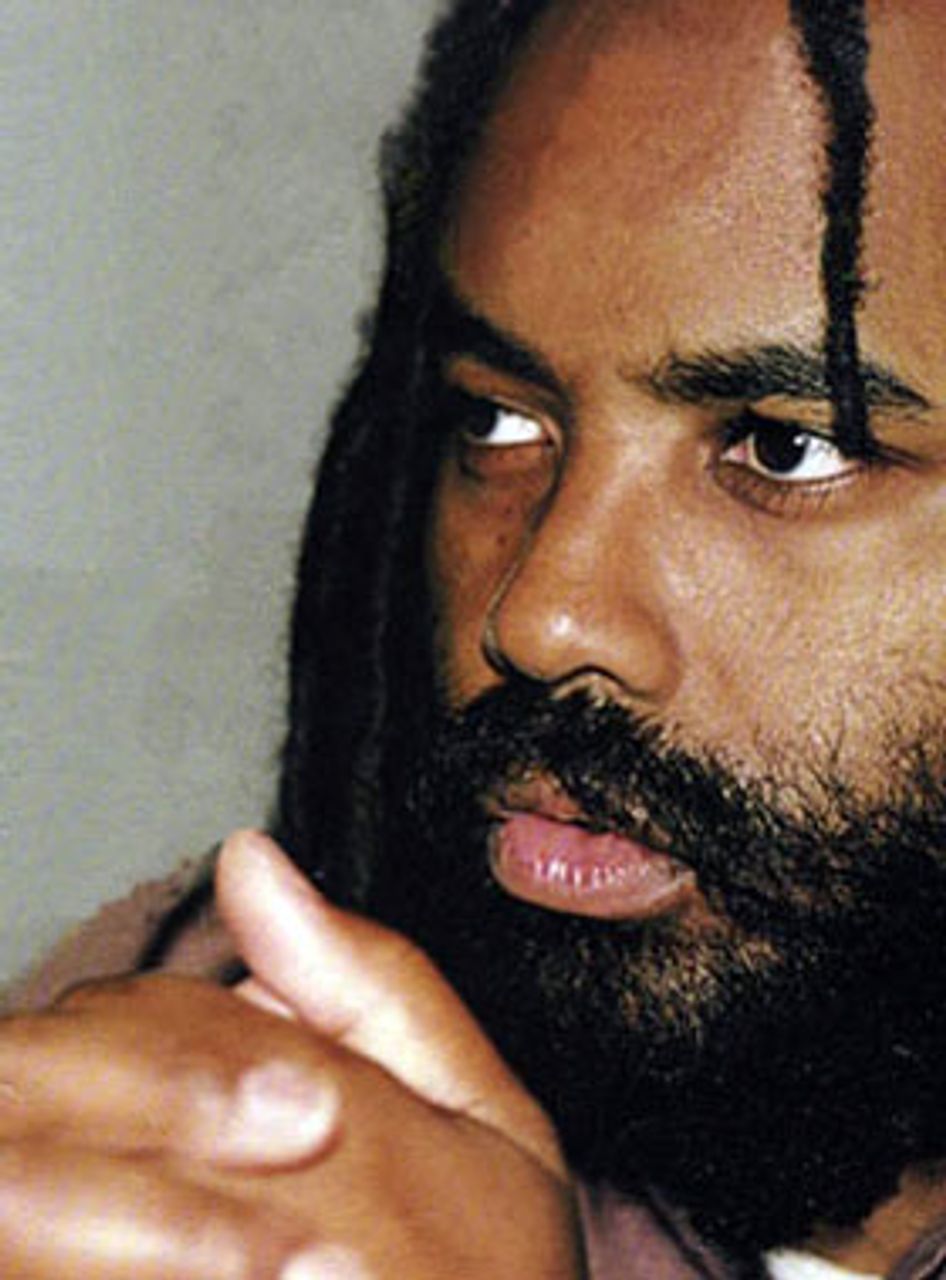

Mumia Abu-Jamal

Mumia Abu-JamalThe United States Supreme Court overturned on January 19 the 2008 ruling of an appeals court that granted death row inmate Mumia Abu-Jamal the right to a new sentencing hearing. A journalist and political activist, Abu-Jamal has been on death row since 1982 when he was convicted for the murder of police officer Daniel Faulkner. Abu-Jamal has consistently maintained his innocence.

At issue in the Supreme Court ruling was whether or not the Third US Circuit Court of Appeals in Philadelphia was correct in finding that both instructions and a verdict form given to the jury at the time of Abu-Jamal’s 1982 trial were “constitutionally deficient” and granting him a new sentencing hearing on this basis.

Attorneys for Abu-Jamal had argued that jurors given the verdict form in question would have incorrectly believed that they could not consider mitigating circumstances in sentencing Abu-Jamal unless there were unanimous agreement of their proof. Instructions from the trial judge, the attorneys argued, only worsened the confusion.

In arriving at their decision to grant Abu-Jamal a new sentencing hearing, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals applied the standard of the US Supreme Court case Mills v. Maryland. That case, decided in 1988, concerned a prison inmate in Maryland who was sentenced to death for having murdered his cellmate. The Supreme Court found that the verdict form and instructions given to the jury in Mills’s case may have caused jurors to believe “they were precluded from considering any mitigating evidence unless all 12 jurors agreed on the existence of a particular mitigating circumstance.” This was ruled unconstitutional.

Court documents in Mills v. Maryland presented an “intuitively disturbing” hypothetical situation in which “All 12 jurors might agree that some mitigating circumstances were present, and even that those mitigating circumstances were significant enough to outweigh any aggravating circumstance found to exist. But unless all 12 could agree that the same mitigating circumstance was present, they would never be permitted to engage in the weighing process or any deliberation on the appropriateness of the death penalty.”

The court vacated Mills’s sentence, writing in its decision, “The possibility that a single juror could block such consideration, and consequently require the jury to impose the death penalty, is one we dare not risk.”

In spite of the virtually identical circumstances in both Mills’s case and that of Mumia Abu-Jamal, the US Supreme Court ruled against Abu-Jamal on January 19, overturning the appeals court’s decision. In doing so, the court invoked a recent case, Smith v. Spisak, it had decided on January 12. In this case the Supreme Court found that the Sixth District Court of Ohio had wrongly extended Mills v. Maryland to declare jury instructions in the trial of John Spisak, Jr. unconstitutional and effectively narrowed the criteria by which such instructions or forms could so be judged.

In light of the Smith v. Spisak decision, the Supreme Court ruled against Abu-Jamal, sending his case back to the Third Circuit Court in Philadelphia, which must now reconsider its decision using the new and more challenging standard. The ruling puts prosecutors one step closer to reinstating the death sentence for Abu-Jamal.

In the years since his 1982 conviction, more and more evidence has come to light pointing toward Abu-Jamal’s innocence. Major witnesses in the case against him have recanted their testimony and alleged that police threatened their lives if they did not testify against Abu-Jamal. In 1999, a man named Arnold Beverly swore in a signed affidavit that he himself had killed officer Daniel Faulkner as part of a hit ordered by corrupt Philadelphia police officers.

There is every indication that Abu-Jamal has been the victim of a police frame-up. Years before his 1982 conviction, the journalist and activist had already drawn the wrath of the police in Philadelphia as a founding member of that city’s chapter of the Black Panther Party and a supporter of John Africa’s MOVE organization. The call for Abu-Jamal’s execution has, from the beginning, been characterized by a special vindictiveness on the part of police and prosecutors. The Fraternal Order of Police maintains to this day a list of known supporters of Abu-Jamal which they have published on their web site.

Over three decades of struggle, Abu-Jamal has become a symbol for opponents of the death penalty. His treatment at the hands of the US criminal justice system has revealed the barbaric nature of capital punishment to a mass audience.

There have been 1,193 executions in the US since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976. During that time, the US has executed prisoners known to be mentally retarded as well as prisoners whose crimes were committed when they were still juveniles. Prisoners sent to their deaths are overwhelmingly poor and working class.

There are currently 3,279 inmates awaiting execution on death row in the United States.