Alex Chilton

Alex ChiltonAmerican musician Alex Chilton, best known as the lead singer of the Box Tops and Big Star, died March 17 at the age of 59. Chilton died of a heart attack after he was taken to a New Orleans hospital complaining of ill health. His death came just two days before he was scheduled to reunite with Big Star in a performance at the South-by-Southwest Festival in Austin, Texas.

Alex Chilton’s career in music spanned four decades. His work has had a significant influence on underground and “independent” rock musicians in the US. As is often the case with the passing of an artistic figure who went largely unrecognized while he or she was alive, there has been a tendency to overrate Chilton somewhat in tributes. Nonetheless, Chilton was a talented performer, and his music is worth considering.

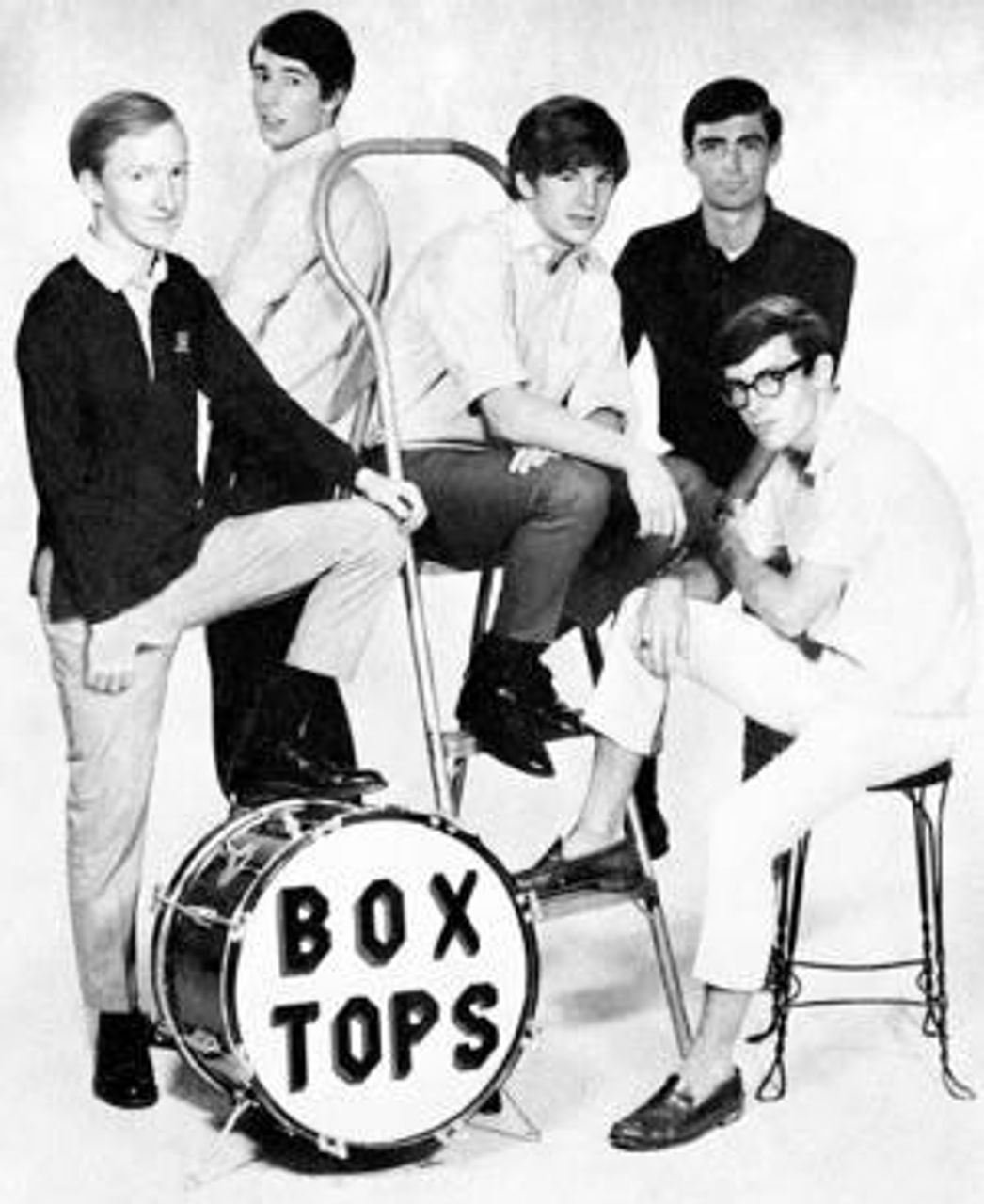

The Box Tops

The Box TopsBorn in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1950, Chilton was immersed in the thriving music community there, featuring its particular blend of blues, soul, country and rockabilly sounds. Chilton’s teenage years coincided with the heyday of Stax Records, home to artists such Otis Redding, Carla Thomas and Isaac Hayes. In the mid-1960s Chilton formed his own band, the Box Tops. The group cut their teeth playing small clubs and parties in the area before finally releasing their first album, The Letter/Neon Rainbow, in 1967.

This album contained the band's first big hit, “The Letter.” Recorded when Chilton was just 16 years old, the song remained at the number one spot on the billboard charts for four weeks. About a man who races home to his former girlfriend when she writes to say she can’t live without him anymore, the song, with its unforgettable first line of “Give me a ticket for an aeroplane, ain’t got time to take a fast train,” has continued to find admirers over the decades. In addition to its irresistible and tightly wound R&B structure, “The Letter” is especially notable for Chilton’s gruff and determined vocals. It is still hard to believe the voice heard on that recording came out of that rather nervous-looking and diminutive teenager.

The Box Tops had the good fortune during this time to find a supporter in Dan Penn, the remarkable Memphis songwriter behind such compositions as “Dark End of the Street” and “Do Right Woman.” Penn produced the early Box Tops recordings, including “The Letter,” and played a significant role in shaping their overall sound.

Soon after the Box Tops disbanded in 1970, Chilton formed his next band, Big Star. This was a very different group, a “power pop” ensemble that drew less on the influences of soul music and more on the pop and rock music of the Byrds, the Beatles and the Beach Boys. Like those groups, Big Star placed a special emphasis on harmony, with a great wave of layered vocals featured on most of their songs. For his part, Chilton had by now abandoned his R&B-tinged vocal delivery in favor of a more straightforward and natural way of singing, an unadorned style that would win him legions of fans in the alternative and “indie” rock musicians who would emerge in the next two decades.

Big Star’s music somehow managed to be anthemic without feeling bloated or pretentious; a song like “Don’t Lie to Me” tends to win the listener over with its youthful, but sincere feeling of protest (Chilton was only 21 when the first Big Star record was released). Songs like “Give Me Another Chance,” “Thirteen,” or “The Ballad of El Goodo,” with its refrain of “Ain’t no one going to turn me ‘round” sung in beautifully harmonized vocals, still deserve to be heard.

Big Star’s first two albums, #1 Record (1972) and Radio City (1974) have achieved a kind of “cult classic” status. As Carrie Brownstein, the guitarist for Sleater-Kinney, wrote on her blog at NPR after learni ng of Chilton’s death, “Musicians and fans have always passed around Big Star songs and albums like a secret handshake.”

If Chilton’s work with Big Star provided an influence on the “indie rock” musicians who would emerge in the 1980s and 90s, his later solo recordings provided something of a blueprint for them. Chilton’s first official solo album, Like Flies on Sherbert (1979), which set the stage for much of his later work, is a stripped-down, “lo fi” garage-rock effort with snarling vocals, brutal guitar riffs and hard-stomping drums.

The album opens with a dissonant garage-rock version of disco giant KC and the Sunshine Band’s “Boogie Shoes.” It’s an impressive barebones, rough-around-the-edges rock ‘n’ roll performance. Listening to the song, it’s as if Chilton is presenting a challenge to disco music and other mainstream, slickly produced works: Come out and say what you mean; don’t be afraid to get your hands dirty and scare a few people.

In Robert Gordon’s book It Came from Memphis, Chilton discussed the album, saying, “Before that I’d been into careful layerings of guitars and voices and harmonies and things like that, and [producer Jim] Dickinson showed me how to go into the studio and just create a wild mess and make it sound really crazy and anarchic. That was a growth for me.” The album has its high and low moments.

Chilton’s was always a very “youthful” music. His best known work was made when he was still a teenager and much of his music retains a mischievous character. It sounds like the music of a young man, which is not in any way to suggest it was not serious or intelligently written. Much of it was.

In their own way, Like Flies on Sherbert and similar Chilton recordings feature some of the same qualities—the “reckless abandon” feeling—that one hears in classic 1950s rock groups such as Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps or the Johnny Burnette Trio. There’s something to be said for the lively and spontaneous music that Chilton made. Some of this is very exciting work. For the listener who can get beyond certain of Chilton’s idiosyncrasies, there are rewarding moments to be found on this album and other later works such as A Man Called Destruction (1995).

However, one also can’t ignore certain disappointing features of the music. One feels at times that Chilton is intentionally limiting himself, ignoring certain of his abilities. All the excess is first trimmed away, and then he keeps on trimming. One can sympathize with his desire to produce something real or essential and to avoid the sounds produced on commercial records, but it’s worth pointing out that screaming one’s head off isn’t necessarily the antidote to over-produced, slick and lifeless music either. One often misses the worked-through compositions and vocal arrangements found in Chilton’s Big Star period.

Chilton, it must be said, is not the only artist to have proceeded in this direction. One need only look at any number of contemporary lo-fi, indie rock groups to see that stripped-down, very small and “personal” works persist as a means of avoiding the emptiness of the mainstream music world. But if one is honest, too much of that kind of music is empty and self-indulgent as well.

Chilton’s art is underdeveloped, as is a great deal of art made over the past few decades, but more often than not Chilton’s work is also honest and even endearingly human. One can feel a real person behind those songs, and that counts for something. And whatever one makes of his efforts, he always put his art above career concerns; he once refused an offer to become the new vocalist for Blood, Sweat and Tears because he felt the band was too commercial.

If Alex Chilton is not quite the major figure he has been made out to be since his death, he nevertheless deserves to be remembered and listened to. Those who choose to explore his catalog of work will find something to admire.