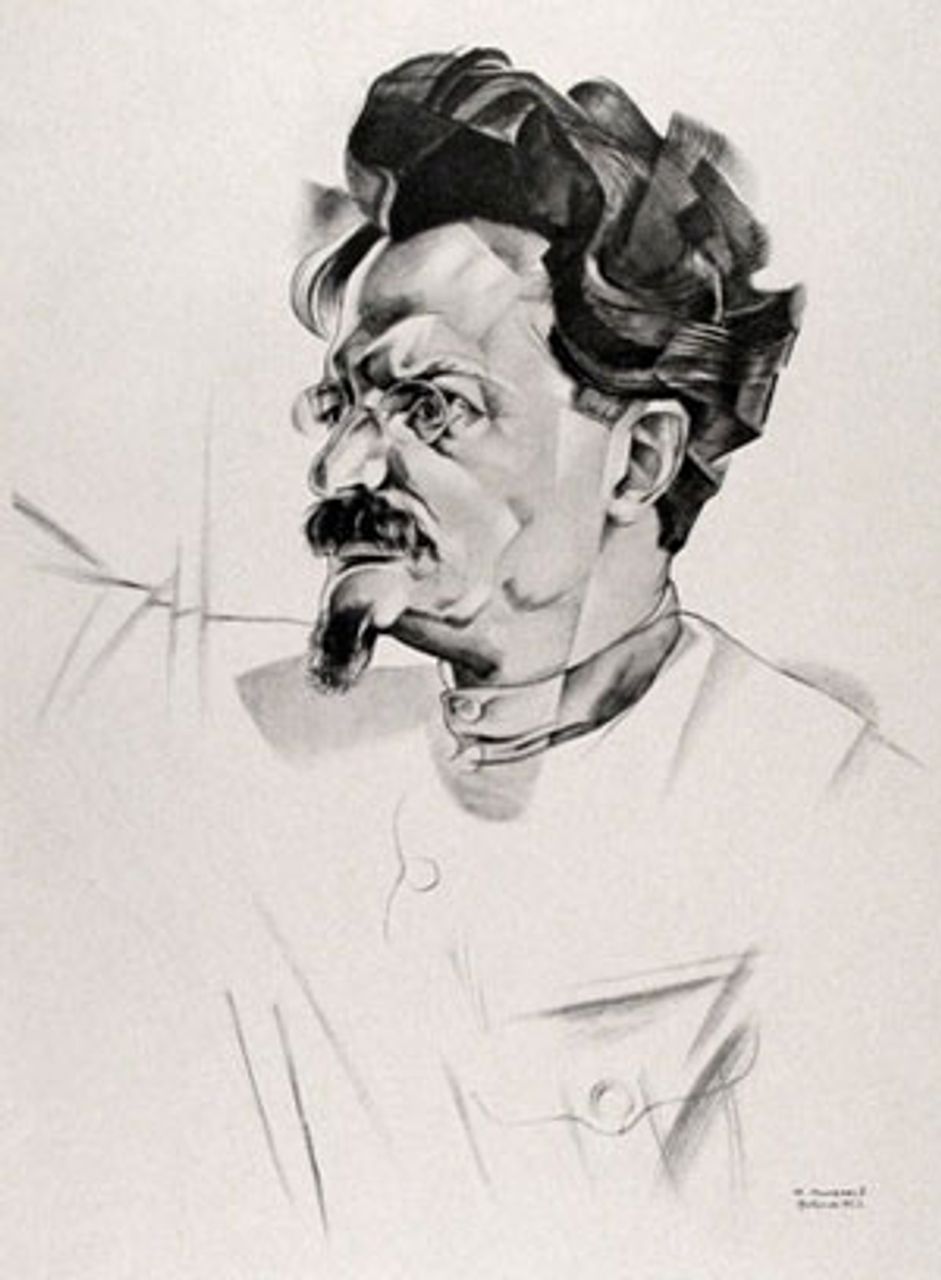

Iuri Annenkov's lithograph of Trotsky

Iuri Annenkov's lithograph of TrotskyIn recent months Leon Trotsky has been the subject of two cultural events in Russia—an exhibition at the State Museum of Political History in Saint Petersburg and a documentary film aired on television. Each of these presentations contained interesting material and provided a more objective evaluation of Trotsky’s historical role than is typically found in Russia today. This is particularly true when considered against the backdrop of the rampant nationalism promoted by Vladimir Putin and his regime’s open efforts to rehabilitate Joseph Stalin. Nonetheless, both the museum exhibition and the film had definite limitations and provided a forum for the repetition of old lies and slanders about Trotsky and the October Revolution.

From November 6 thru December 9 of last year Lion of the Revolution: One Hundred Thirty Years Since the Birth of Lev Davidovich Trotsky was open to visitors in the building that had served as the headquarters of the Bolshevik Party in the spring of 1917.

During the Soviet era, this site, which had been the mansion of the ballerina Matilda Kshesinskaia, housed the Museum of the Revolution. At the time, its collection and displays were heavily influenced by Stalinism, precluding any positive mention of Trotsky and his place in the history of the Russian Revolution.

Although last winter’s exhibition was limited to a modest hall on the periphery of the museum and it lasted only one month, its very name, as well as the character of some of the displays, reflected a sympathetic attitude towards an examination of Trotsky’s life.

The official web site of the Russian Ministry of Culture, which oversees the State Museum of Political History, stated in its commentary about the exhibition: “A professional revolutionary and political figure, Trotsky was one of the leaders of the October insurrection of the Bolsheviks in Petrograd; he made no small contribution to the establishment of the Soviet state and the creation of the Red Army during the Civil War.”

The exhibition’s printed material contained the same lines and added, “In the 1930s he was the most consistent and merciless exposer of Stalinism.”

The theory of “permanent revolution,” it stated, was developed by Trotsky during the period when he “returned to Russia in 1905 and actively participated in the first Russian Revolution.” The essence of this theory, it continued, “was expressed by him in the following way: ‘The socialist revolution begins on the national arena, develops on the international arena and ends on the world arena.’”

A significant number of the displays included in the exhibition had been preserved by the museum’s staff at their own personal risk. These included photographs of the participants of the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party in 1903, a photograph of Trotsky in a prison cell at the Petropavlovsk fortress, a lithograph by Iuri Annenkov dated 1926, Trotsky’s pamphlet Our Political Tasks published in 1906 in Geneva, and an engraving “In Memory of Trotsky” by the Mexican artist Vladimir Kibalchich (1920-2005), son of the famous revolutionary Victor Serge.

The museum also presented several original copies of letters and articles by Leon Trotsky and his son, Leon Sedov, from the beginning of the 1930s. In particular, there were letters addressed to the cipher officer at the Soviet mission in Oslo, P. S. Kuroedov. These documents were discovered by one of the former members of the Soviet special services.

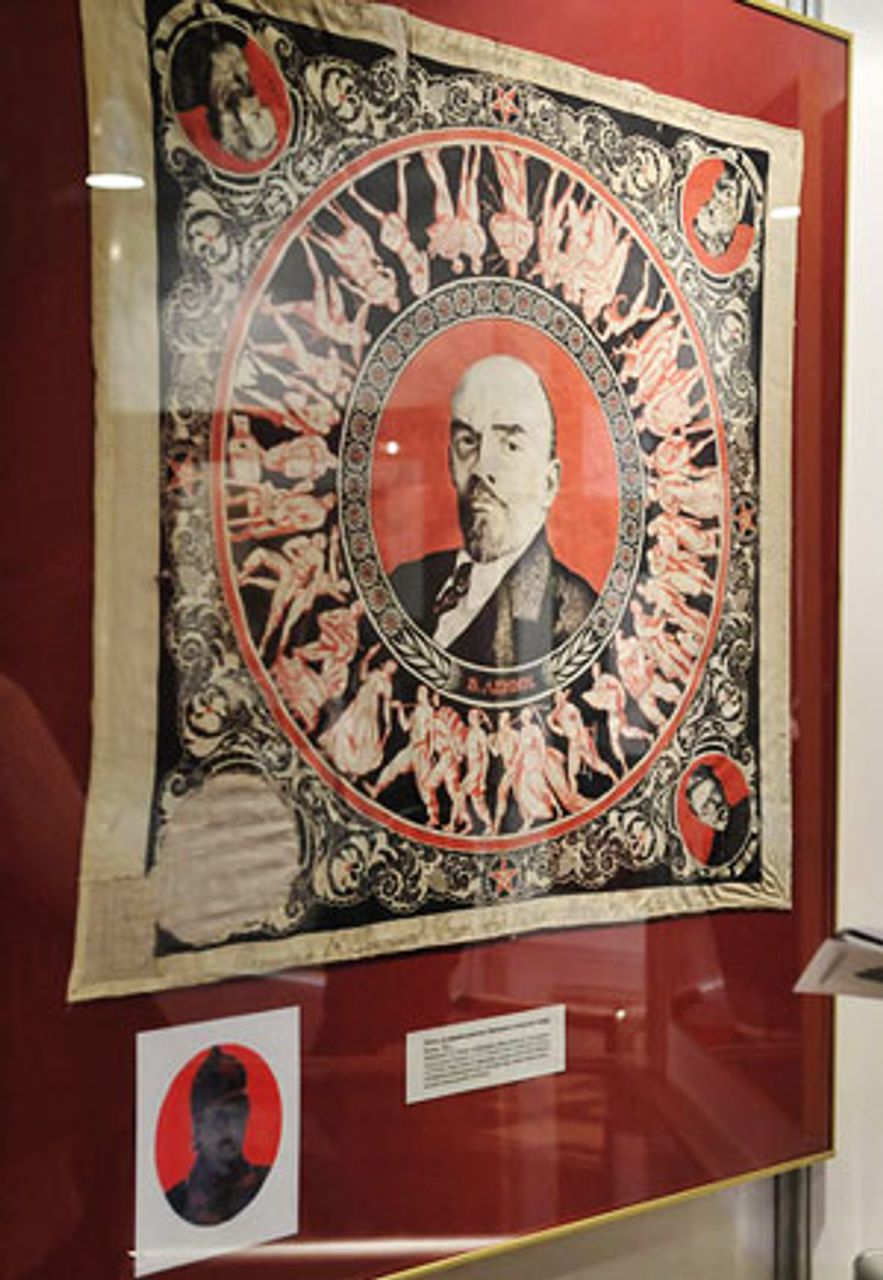

Kerchief with portrait of Trotsky removed

Kerchief with portrait of Trotsky removedAmong the displays one could see a kerchief given to delegates of the First All-Union Teachers’ Congress in 1925. A large portrait of Lenin was sewn into the middle of the kerchief, and on the corners there were portraits of Marx, Engels and Kalinin. On the fourth corner there had been a portrait of Trotsky, but it had been cut off and replaced by a smaller piece of cloth.

One more item on display was a previously classified archival document—a draft of an article for the newspaper Pravda about Trotsky’s assassination with Stalin’s handwritten changes. The headline, “Trotsky’s Inglorious Death,” had been changed by Stalin to “Death of an International Spy.” A correction was made to the end of the text as well. The last sentence had been crossed out: “One more figure, an inveterate spy and agent, the cursed enemy of the workers, has left the political arena of the capitalist world.” In its place it was written that Trotsky “had become a victim of his own intrigues, betrayals, treacheries and heinous crimes.”

However, despite its undoubted value as living testimony, on the whole the exhibition’s material left an ambiguous impression. As the museum’s press service noted, the task of the exhibition was “to present various points of view about the personality of the revolutionary: both the negative official Soviet evaluation and the positive assessment, which is sometimes romanticized.”

In taking this stance, the argument was being made that a reproduction of a large number of the old lies about Trotsky and attacks on him was a necessary element of an “objective” account of history. Unfortunately, the overall balance of the displays gave too much emphasis to the “negative official Soviet evaluation,” especially since this “evaluation” is already well known and has nothing to do with the historical truth.

A prominent place, for example, was given to caricatures of Trotsky. In one part of the hall there were satirical posters from the time of the Civil War that were made by counter-revolutionary, anti-communist White-Guard artists. On the opposite side of the hall were caricatures from the time of the Moscow Trials in the mid-1930s, when Trotsky was declared “enemy number one of the Soviet regime.”

Trotsky at work with the Dewey Commission

Trotsky at work with the Dewey CommissionThe exhibition essentially returns to the appraisal that predominated during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, when Trotsky’s partial rehabilitation was accompanied by many of the old negative clichés about his personality and the international revolutionary socialist program that he embodied. In the Lion of the Revolution, the verbal recognition of Trotsky’s historical role is more than compensated by the overall negative visual impression created by the false charges and vicious lies made against him.

Thus, it is difficult to agree with the claim made by Elena Kostiusheva, deputy general director of the museum, that the exhibition is a definite step forward in the development of “domestic Trotsky studies.” Rather, it would be more accurate to say that Lion of the Revolution was a symbolic gesture, the making of which was more significant than its actual content.

The viewer is left with a similarly ambiguous impression of Trotsky from the documentary film An Ice Axe for Trotsky: Chronicle of an Act of Revenge, which was broadcast on the evening of March 4 on the main state television channel, Rossia.

This 55-minute film, written by Irina Chernova and directed by Maksim Faitelberg, markedly differs in a positive way from similar products of recent years, such as the documentary film by Elena Chavchavadze, Lev Trotsky: The Secret of World Revolution.

This latter film, which was shown at the beginning of 2007, depicted Trotsky as the enemy of the Russian people and state par excellence. Over the course of his life he was allegedly an agent of virtually every imperialist government in the world and also served as a weapon in the hands of the Jewish “bankers’ international.”

The trailer for Chavchadze’s film declares: “Lev Trotsky was one of the most pernicious figures in the history of Russia in the 20th century. His name is linked with the key events of the state’s tragedy—the so-called proletarian revolution, the catastrophic Brest-Litovsk Treaty, the Civil War, the ‘Red Terror’ and the plundering of the country.”

In contrast, the new film by Chernova and Faitelberg gives a more sober account of the historical record. “Trotsky had a remarkable biography. During the October days, Trotsky played a decisive role, while Stalin was the man who slept through the revolution,” says the narrator, Professor of History Oleg Budnitskii. “People followed Trotsky in 1917 and in 1918 he created the Red Army,” he continues.

Another participant in the film, Andrei Sakharov, the director of the Institute of Russian History, states, “The complete falsification of history is contained in the Short Course of the History of the VKP(b). Everyone who was close to Trotsky, starting with 1918, was shot.”

The film relates how the Dewey Commission, which investigated the charges made against Trotsky during the Moscow Trials, unquestionably proved that Stalin’s accusations were completely groundless and established Trotsky’s innocence before world public opinion.

At the same time, the film repeatedly presents evaluations that are borrowed from the stereotypical charges made against the October Revolution and its leaders. For example, when the film deals with the Stalinist genocide of the Old Bolsheviks, it adds the completely unfounded commentary that “under Trotsky” the scale of the repressions would have been no less. Budnitskii insists that the policy of the “Red Terror” that was once launched by Trotsky against class enemies had turned against himself.

When the film addresses the tragic fate of Trotsky’s children, who were killed by Stalin, this is supplemented by the comment that Trotsky justified the murder of the tsar and his children as politically expedient. From this, apparently, it must follow that once again “Trotsky’s methods” turned against him.

All these superficial “analogies,” using facts torn out of historical context, lower the scientific value of the film and expose its hidden secondary goal—to equate the dramatic episodes of the revolution with the crimes of Stalinism and thereby to discredit the very idea of the socialist transformation of society as an alternative to the violence and oppression of the capitalist world order.

Nevertheless it is necessary to note the appearance of these more sympathetic assessments of Trotsky within the framework of the Russian cultural “mainstream.” How serious are the intentions of those behind this? The answer is bound up with a more general evaluation of the sociopolitical processes developing in contemporary Russia.

First of all, the decline in historical knowledge and the degeneration of the social and political atmosphere that resulted from the restoration of capitalism have created an objective demand for true historical knowledge. People have become tired of endless fake “exposés” and of light-minded speculation.

The “blank spots” in history that were mentioned so often in journalism during the time of Gorbachev’s perestroika have not so much been “filled in” over the two post-Soviet decades, as they have been used as a reason to create a new school of historical falsification in the service of a privileged layer of private property owners.

On the other hand, the growing conflict within the Russian ruling elite, manifest in tensions between President Dmitri Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin has ideological dimensions.

Putin’s rise to power was accompanied by a sharp shift in official ideology and propaganda in the direction of Russian nationalism, authoritarianism, and the rehabilitation of Stalinism. In contrast, the liberals of the 1990s and their ideological descendants, who are an influential voice in Medvedev’s entourage, base themselves on the experience of the 1980s and 1990s. At that time, the exposure of the crimes of Stalinism was used to discredit the socioeconomic foundations of the Soviet Union and to advance a program of capitalist reforms.

In those years in particular, these layers attempted to use the criticism of Stalin made by Trotsky for their own goals. They proceeded from the assumption that the masses would be able to adopt a critical view of the theory of “socialism in one country,” but not assimilate the genuine internationalist spirit of the October Revolution.

Similar calculations stand behind today’s attempts to tell part of the truth about Trotsky. Layers of the liberal intelligentsia, who discredited themselves in the past, are seeking sympathy among the workers and flirting with episodes of heroic struggle for their own interests. They hope to maintain the masses under their control with carefully measured manipulation.

Only in a very remote and distorted form do these efforts reflect the subterranean and ever growing interest in the history of the Russian Revolution that exists among broad layers today.