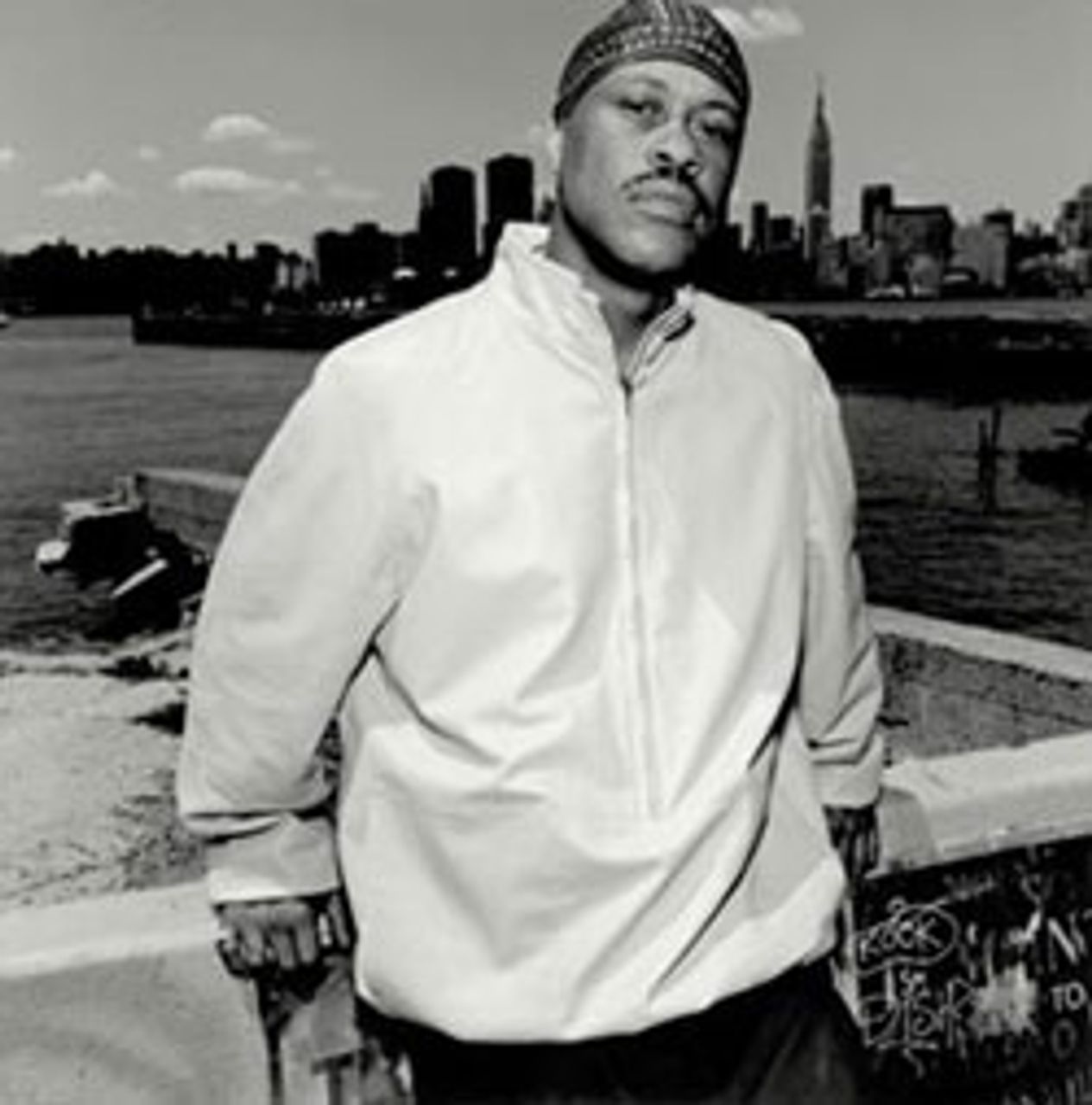

Keith Elam, known as Guru

Keith Elam, known as GuruRapper Keith Elam, who recorded under the moniker of Guru, died on April 19 at the age of 48. Elam had been battling multiple myeloma for more than a year. In February, Elam suffered cardiac arrest and fell into a coma from which he never regained consciousness. His death on the morning of April 19 was followed by an outpouring of appreciation from fans and fellow musicians.

Elam was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on July 17, 1961. His father was the first black judge appointed to the Boston Municipal Court and the founder of the Massachusetts Black Judges Conference. Elam’s mother was co-director of the Boston Public Schools Library Program and a founding board member of the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail.

Elam graduated from Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1983 and eventually moved to New York where he worked for a time as a social worker. In New York, Elam met Christopher Martin, who had come from Houston, Texas, to begin a career in music. Martin would eventually come to be known as DJ Premier and is today rightly considered one of the most talented musicians hip hop has yet produced. The duo formed Gang Starr and released their first album, No More Mr. Nice Guy, in 1989.

While their name may suggest otherwise, Gang Starr was not a “gangster rap” group but rather one of several hip hop groups formed in the late 1980s and the 1990s considered “socially conscious.” Among their like-minded contemporaries were KRS-One and Boogie Down Productions, Public Enemy, and A Tribe Called Quest. While their level of consciousness may be exaggerated, to be sure all of these musicians made, in some way, attempts at social criticism through their art and were influential and innovative figures in the genre.

Gang Starr released six albums between 1989 and 2003. On these recordings, one can find some of the most exciting sample-based compositions of the 1990s. Guru’s vocal delivery on these recordings was notable for his mellow, almost monotone style. His voice was forceful but also retained a gentle, even soft quality about it. At a time when rappers were experimenting with faster deliveries and a more rhythmically complex blending together of lyrics, Guru maintained a relatively slow and easy-going rhythm. He wasn’t the wordsmith that contemporaries like Rakim or Big Daddy Kane were, but he made his mark.

Among the best songs found on Gang Starr’s albums were the narrative works vividly painting portraits of street life in New York. “Just to Get a Rep,” one of the group’s best-known recordings, was about “stick up kids” who mugged people in order to gain reputations for themselves. “They got their eye on the gold chain that the next man’s wearing,” Guru rapped, “It looks big but they ain’t staring. Just thinking of a way and when to get the brother. They’ll be long gone before the kid recovers. And back around the way he’ll have the chain on his neck, claiming respect just to get a rep.”

In “Code of the Streets,” Guru rapped about car thieves and drug dealers, saying, “I gotta have it so I can leave behind the mad poverty, never having always needing. If a sucker steps up, then I leave him bleeding. I gotta get mine, I can’t take no shorts.” In delivering these lines, Guru never glorifies or makes excuses for criminality and backwardness as has so much of rap music, frankly. Instead, one gets a sense here and in other Gang Starr recordings of the enormous social tragedy involved in these lives. Inhabiting these characters, Guru’s voice is worn and weary.

The first verse in “Betrayal” from 1998’s Moment of Truth is among Guru’s most vivid and disturbing. “Check the horror scene: the kid was like twelve or thirteen, never had the chance like other kids to follow dreams. Watched his father catch two in the dome and to the spleen, nothin’ but blood everywhere, these streets are mean. They spared his life, but killed his moms and his sister Jean....” DJ Premier’s slow, sorrowful musical accompaniment to these lyrics is unforgettable.

While their narrative works were often strong and the production work of DJ Premier had few equals, Gang Starr were not without their limitations. Having been influenced by the popularity of “battle raps” that were prevalent in hip hop during its earliest years, in which one rapper would try to outdo and humiliate another with their lyrical abilities, Gang Starr included a great deal of such material on their albums.

Song after song in Gang Starr’s catalogue of work was devoted to how much better they were than other rappers. Some of these songs, such as “Step in the Arena,” are lively and entertaining, featuring a kind of playfulness of language that draws in the listener. Far too many of these songs, however, are simply repetitive and self-aggrandizing. Some of it feels formulaic; it would take a considerable amount of time to list all the instances in which Guru described his lyrics as gunfire of one kind or another (“Who’s the suspicious character strapped with sounds profound similar to rounds spit by Derringers....”).

Attempts by the group to create positive “message” songs or more explicit political statements were even worse. These songs reveal the limitations not just of their own work, but of virtually all of the so-called socially conscious hip hop artists of the 1990s. Attaching themselves to one form of identity politics or another, these more politicized works leave one shaking one’s head.

There are vague slogans relating to “positivity” and cultural awareness. The need for black ownership of businesses and other forms of racial solidarity are continually promoted. The adherence to quasi-nationalist politics took its toll on the work of these young artists. Many who appeared innovative and serious during the 1990s have turned out more and more “commercial” and, to be blunt, backward and useless products in more recent years.

As for Gang Starr, their best work (“Just to Get a Rep,” “Code of the Streets,” and others) tends to get lost among their weaker material. One can’t help but be disappointed in the group’s lack of consistency. At their best, they contributed something significant and moving. But how often did they achieve that? Not often enough, ultimately.