This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Strike wave grips Brazil

A rally of Brazilian metalworkers in 1990

A rally of Brazilian metalworkers in 1990A growing crescendo of strikes and occupations in Brazil threatened the new government of Jose Sarney, who had been installed after the death of Tancredo Neves. Neves had won the first presidential elections in Brazil after a 21-year military dictatorship.

Auto workers in Sao Paolo occupied plants owned by General Motors and Volkswagen on the weekend of April 27 and 28, blocking management from leaving the factories. Sao Paolo’s auto workers were in their fourth week of strikes against GM, Volkswagen, Ford and Mercedes.

Transit workers in Rio de Janeiro entered their third week on strike. Workers in both industries demanded wage increases greater than the inflation rate of 226 percent, annualized. Metal workers also demanded a reduction in the work week from 48 to 40 hours.

Sarney responded by raising the national minimum wage of $14 per week by 6 percent, and by turning to the formally outlawed Communist Party for political support. After talks with Sarney, CP deputy Luis Guedes said that inclusion of the Stalinists in Sarney’s proposed “national dialogue” could guarantee the “stability of Brazilian democracy.” Workers Party head Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (‘Lula”) demanded fresh elections in response to the crisis.

50 years ago: California executes Caryl Chessman

The restraining chair in

The restraining chair inCalifornia's San Quentin prison

where Caryl Chessman was

executed

On May 2, 1960, Caryl Chessman was sent to his death in a California gas chamber after the state’s liberal Democratic Governor, Edmund “Pat” Brown, refused to grant clemency or a stay of execution. Chessman was 38.

Los Angeles police had pegged Chessman as the “Red Light Bandit” who robbed, and in a few cases, raped, motorists in parked cars after shining a red light on them and convincing them he was a police officer. Chessman, who maintained his innocence to the end, was convicted in 1948 and sentenced to death for abduction with intent to commit bodily harm under California’s “Little Lindbergh Law.”

Also convicted of rape and robbery, the application of the abduction charge—Chessman was accused of moving women a matter of feet before raping them—allowed for the death penalty. The Lindbergh Law was repealed in 1954, and those who were convicted under it had their sentences commuted to life imprisonment—but not Chessman.

The central evidence against Chessman was a forced confession, which he retracted, and the fact that a red light was found in his car. His record as a former criminal was also used against him, although he had no history of sexual assault. Chessman did not match the description given to police by rape victims.

The Chessman execution became the focus of a major international campaign against the death penalty. This was owed in large measure to Chessman’s own articulate fight against the sentence.

After unsuccessfully representing himself in court—it is widely held his poor performance contributed to his conviction—Chessman worked tirelessly from behind bars, writing four widely read books—the memoirs Cell 2455, Death Row (1954), Trial by Ordeal (1955), and The Face of Justice (1957), and the novel The Kid was a Killer (1960). Banned by California from writing, Chessman wrote late at night and disguised his work as legal notes in order to clear the prison censors. Cell 2455, Death Row became a Hollywood feature film in 1955.

Among those appealing to Brown for clemency on behalf of Chessman were writers Aldous Huxley, Norman Mailer, Robert Frost and Ray Bradbury; comic Lenny Bruce; former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt; and rock musician Ronnie Hawkins, who recorded “The Ballad of Caryl Chessman (Let Him Live, Let Him Live)” in 1960.

In a cruel twist, a judge issued a last minute stay of execution after being presented a photograph of a man named Terranova who matched the description of the Red Light Bandit and who allegedly had a history of sexual assault. A call from the judge’s office to San Quentin came seconds too late. The cyanide pellets had already been dropped into the sulphuric acid, producing a deadly gas that would imperil those observing the execution if the gas chamber were opened. Eight minutes later, Chessman was dead.

75 years ago: Sakdal uprising in the Philippines

The Philippines

The PhilippinesOn May 2, 1935 the Sakdalista movement launched an uprising in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. The peasant-based rebellion opposed an oppressive system of land ownership that enriched a small elite while leaving masses of tenant farmers in poverty. It also demanded the independence of the Philippines from the United States.

The Sakdalista movement had been founded in 1930 by Benigno Ramos, and a Sakdal political party was formally established in 1933. In addition to complete independence from the US, the Sakdalista movement demanded a reduction in taxes on the poor and major land reforms, including the dissolution of large estates.

The May 2 uprising saw fighting throughout the Central Luzon region, with tens of thousands of Sakdalistas taking part in the revolt. The rebels captured municipal buildings in several towns. Fighting in Cubuyao, Laguna was especially intense, with dozens killed and government troops forced to call for reinforcements and additional weaponry. The rebels were able to completely isolate Manila, cutting off all communications and transportation in the area.

In spite of its scope and ferocity, the rebellion fell apart in its second day. The fighting resulted in roughly 100 casualties, more than half of whom were Sakdalista fighters. Benigno Ramos was forced to flee to Japan following the defeat and his Sakdal party was essentially dissolved.

100 years ago: After spate of deadly disasters, US regulates coal mining

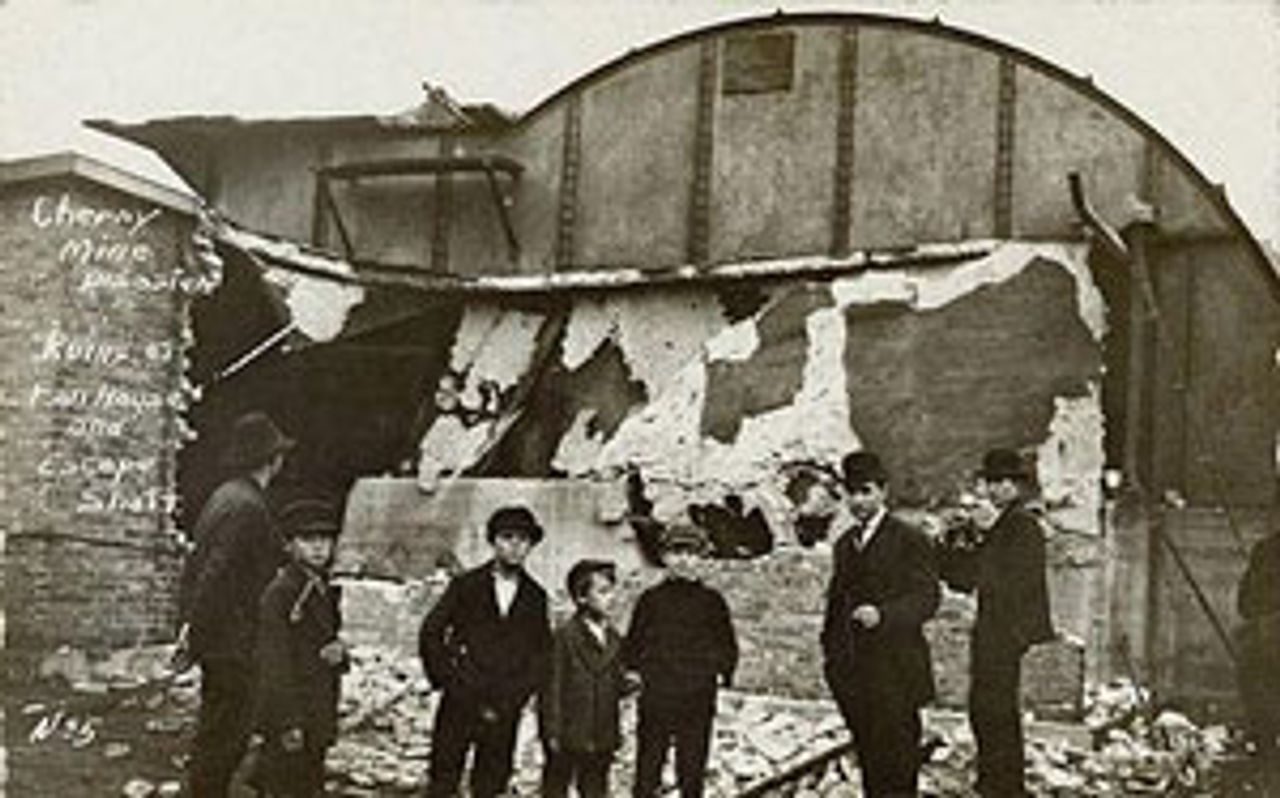

The Cherry mine head, where 159 men and boys died

The Cherry mine head, where 159 men and boys diedin 1909

On May 2, 1910 the US Senate voted to create the US Bureau of Mines within the Department of the Interior in response to a series of deadly coal mining accidents that had claimed the lives of hundreds of miners in recent months.

In the two weeks prior to the bill’s passage, 40 coal miners had been killed at a mine near Mulga, Alabama, and 18 more had died in a mine disaster in Amsterdam, Ohio. Six months earlier, 259 men and boys died in a mine fire in Cherry, Illinois, their widows and children left largely without compensation.

In 1907, 3,242 miners died while on the job, including 358 in the nation’s worst-ever mine disaster, at Monongah, West Virginia.

The formation of the Bureau of Mines was an example of Progressive era reformism, which sought to regulate and modify the most egregious elements of industrial capitalism. The move toward regulation came in response to the national growth of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), which had in recent years organized the bituminous coal fields stretching from Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia in the east to Illinois and Iowa in the west, as well as eastern Pennsylvania’s anthracite fields. Socialists exerted a powerful influence in the UMW, and the demand for the nationalization of the mines was being persistently raised.