This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: French agents bomb Greenpeace boat in New Zealand

A memorial to the Rainbow Warrior

A memorial to the Rainbow WarriorOn July 10, 1985, the Greenpeace vessel the Rainbow Warrior was bombed and sunk in the harbor of Auckland, New Zealand by ten French secret agents from the DGSE spy agency (Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure.) Dutch photographer Fernando Pereira drowned in the attack.

It was later revealed that French President Francois Mitterrand had personally ordered the attack on the boat, which was engaged in efforts to obstruct French testing of nuclear bombs in the South Pacific.

Most of the French agents escaped New Zealand after the bombing, which was carried out in flagrant violation of international law. However, two were captured by New Zealand and eventually sentenced to ten-year jail sentences after entering into a plea bargain and accepting manslaughter charges.

In retaliation for the arrests, the Mitterrand government threatened the New Zealand Labour government of David Lange with a European Economic Community embargo. This brought Lange to heel. He accepted a French apology and minor reparations in return for releasing the killers after two years to French custody. New Zealand was left isolated by its allies the United Kingdom and the US. Washington was angered by Lange’s prohibition on the transport of nuclear weapons through New Zealand waters.

50 years ago: Civil war in the Congo after Lumumba election

Swedish soldiers during the Congo Crisis

Swedish soldiers during the Congo CrisisDays after the inauguration of nationalist Patrice Lumumba as prime minister of the Congo, Western powers and mining interests provoked the beginning of a civil war and the virtual abandonment of the government by the military.

Lumumba made the decision to leave the new national army in the charge of Belgian officers, enraging low-ranking Congolese officers. The Belgian commander of the Leopodville regiment, Emile Janssens, provoked the African soldiers, gathering them and writing on a placard, “After independence = before independence.” Lumumba made matters worse by granting raises to all government employees except for the military officers.

By July 5, the army was in open revolt across the country, with Europeans fleeing in droves. Belgium seized on the threat to European settlers to recommence military operations in the nation, in open violation of the one-week-old country’s sovereignty. To deal with the disaster, Lumumba determined to reorganize the military as the Armee Nationale Congolaise. He made the fateful decision of placing his secretary—who was likely a Belgian spy—Joseph Mobutu in charge of the new force.

By the end of the week, on June 11, Moise Tshombe declared Katanga province independent and immediately received the backing of Belgium and its force of 6,000 soldiers stationed there. Katanga was rich in copper, uranium, tin, zinc, uranium and cobalt—mineral wealth dominated by the Belgian mining concern Union Miniere.

75 years ago: FDR signs Wagner Act into law

Roosevelt signs the Wagner Act

Roosevelt signs the Wagner ActOn July 5, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act into law. More commonly known as the Wagner Act, after Robert F. Wagner, the US senator who introduced the bill, the law recognized the right of workers to engage in collective bargaining, to be represented by a union of their choice, and to take strike action.

The law was a blow against the “open shop” and company unions favored by employers, and was the second attempt at regulating labor practices following a Supreme Court’s ruling that declared unconstitutional the National Industrial Recovery Act.

Section 7 of the Wagner Act stated “Employees shall have the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations,” and to “bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing.” But while the act gave certain protections to organizing workers that contributed to a growth of union membership throughout the 1930s, it also sought to restrain the growing militancy of the working class.

Roosevelt wagered that if the main trade unions, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the young Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), were promoted as the legitimate representatives of the working class, they could be absorbed into the “New Deal Coalition” and serve as a barrier to the militant struggles of the working class that had taken on near-insurrectionary proportions. The Wagner Act sought to move labor disputes off the streets and put them in the arena of federal arbitration boards.

The previous year had seen a wave of city-wide strikes, including the San Francisco longshoremen's strike, the Toledo Auto-Lite strike, and the Minneapolis truck drivers’ strike. In the Minneapolis strike, in particular, the American Trotskyist movement played the leading role.

The Wagner Act also granted the president the right to bring a strike to an end in the event that it was found to “imperil the national health or safety.”

100 years ago: 60,000 cloakmakers strike in New York City

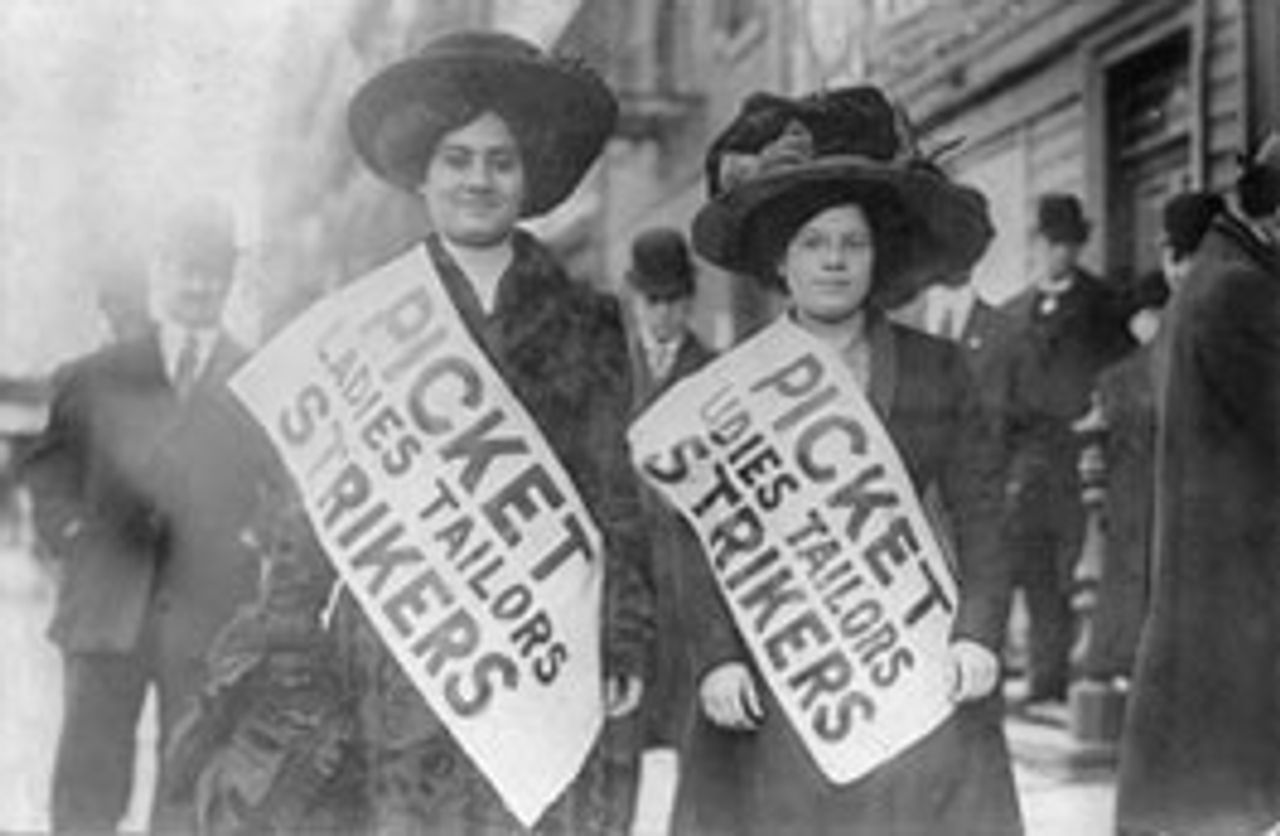

New York City strikers

New York City strikersOn July 7, 60,000 cloakmakers went on strike in Manhattan and elsewhere in New York City, responding to a call to strike printed in Yiddish, Italian and English by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). The spirit of socialism infused the strike, particularly among the Jewish immigrants who dominated the needle trades in New York.

The strike lasted for two months and drew the attention of prominent reformers who attempted to mediate it, including attorney Lewis Brandeis. It was the second major strike to grip the garment industry in months, following closely the bitter “Uprising of the 20,000” strike of Manhattan shirtwaist makers.

Ultimately, the cloakmakers’ strike, which was then called “the Great Revolt,” was resolved through what became known as the “Protocol of Peace,” overseen by Brandeis. The ILGWU took the power of negotiation out of the hands of the workers’ strike committee and concluded a pact that realized gains for workers and “preferential” recognition of the union, in exchange for the union’s assistance in rationalizing the garment industry to the benefit of the largest employers, who faced constant pressure on profits from small-scale producers and sweatshops.