Solomon Burke—who died in the Netherlands last week, aged 70 (although there is some controversy about his date of birth)—was a great soul singer with hits such as “Cry to Me,” “Tonight’s the Night,” and “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love.”

Burke’s importance lies not so much with his performance values—he was not as gifted a singer as Sam Cooke or a songwriter of the calibre of Marvin Gaye—but he is widely credited with being the originator of soul music. A credit he took every chance to claim.

Burke was born on March 21, 1940 in an upper room at the United Praying Band for The House of God for All People in West Philadelphia with the sounds of horns and bass drums welcoming him to the world.

As he said: “Gospel was part of my total career, not just something I started with, but something I live with, as my foundation and rock. I grew up a normal black kid in the ghetto, exposed to all kinds of music that influenced me as a songwriter and recording artist. I loved country, big band, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Perry Como, Doris Day, Gene Autry, Ray Charles, Dinah Washington, Roy Rogers—all of whom in some way inspired me to reach my goal of doing something extraordinary with my life that would connect with people. Every song I write has a different meaning, and each one is special because it depends on the situation of the moment in time when I wrote it. I am always flattered by the way other artists interpret my songs, but in the end it doesn’t matter how they do it. It’s more important that the message of the song reaches people.”

He began singing in church when he was seven, and was strongly influenced by the evangelical zeal of his grandmother Eleanor. This fervor and conviction for the church never left him, and he dealt with secular audiences by preaching the same gospel of peace and love.

At this early age he won the nickname “The Wonder Boy Preacher” by his efforts in the pulpit, and he soon after hosted his own gospel radio show, Solomon’s Temple, in Philadelphia. Following a falling out with his manager he decided to attend mortuary school and went to work for his aunt, who owned a funeral parlour business.

He continued to sing nonetheless and was eventually signed by legendary producer Jerry Wexler in 1960 as a result of his recording, aged 14, the million-selling gospel hit, “Christmas Presents From Heaven” for the independent Apollo label. Wexler—never one to miss the boat—signed him immediately. Wexler later wrote in his memoirs that “Solomon was churchy without being coarse, his melisma subtle and restrained, his voice an instrument of exquisite sensitivity. His skills remain intact, ringing emotional depth out of every gentle sigh or thunderous holler.”

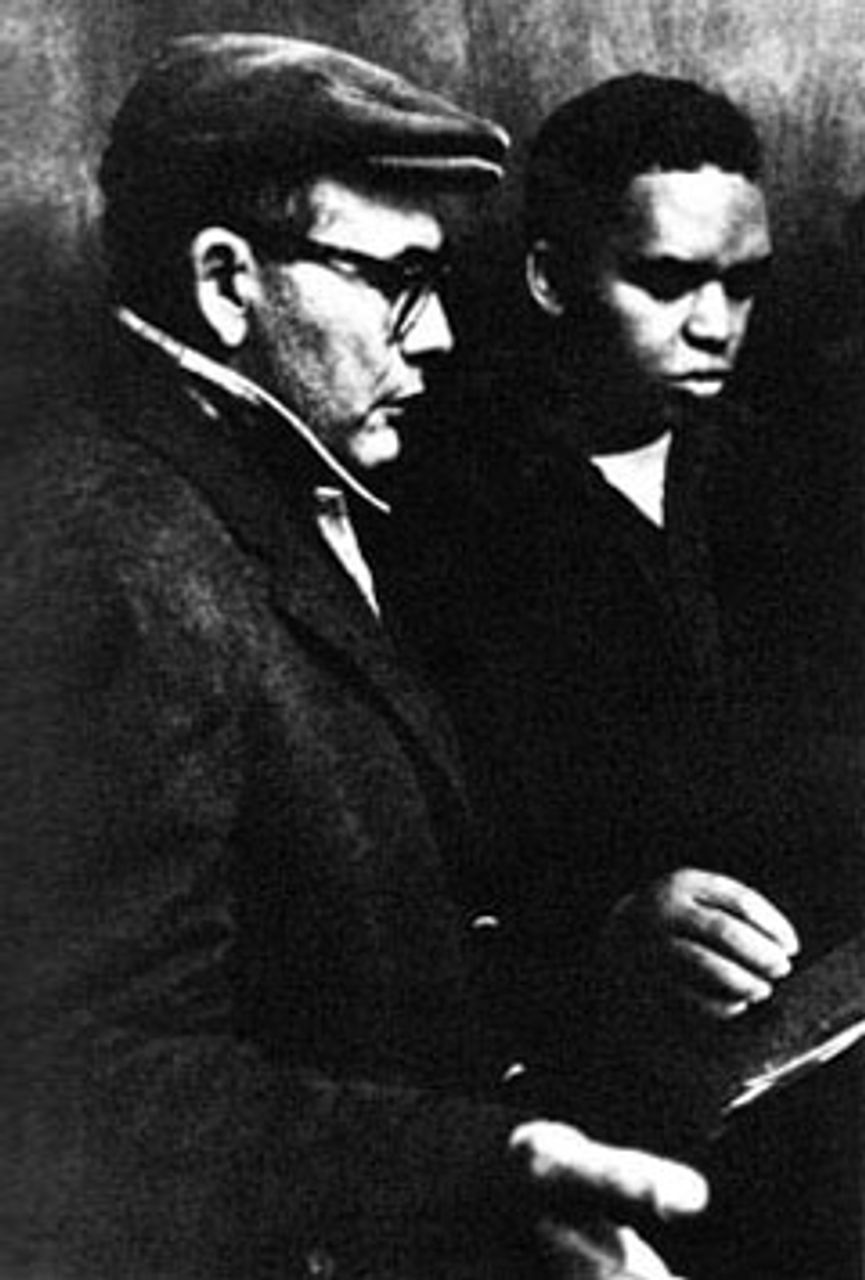

Jerry Wexler (left) and Solomon Burke

Jerry Wexler (left) and Solomon BurkeIn 1961 he had a minor hit with “Just Out of Reach,” with a rhythm and blues country-flavoured feel but his career really took off when he found his authentic soul voice the following year with the release of all time great soul classics, “Cry to Me” (featured prominently in the movie Dirty Dancing many years later), “Down in the Valley,” “If You Need Me,” “Goodbye Baby” and the wildly rambunctious “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love.”

There is an ongoing debate as to whether or not Burke’s recordings in this period were the first true soul recordings, with many championing Ray Charles’s early hits in the 1950s, but 1961 was the first recorded use of the word “soul” to describe a form of music. Legend has it that it arose because Burke objected to the term “rhythm and blues,” being used to describe his songs. He found this too close to the “devil’s music” connotation and Wexler calmed his anxieties by improvising the word “soul” to convey the spiritual side of Burke’s music.

Burke constantly toured the US, with all the stresses that entails. On one occasion he was hired to play for a large outdoor event in Mississippi. The organiser told him play his hit “Down in the Valley.” But as audience filed in wearing white sheets, hoods and masks—he realised that he’d been booked by Ku Klux Klan. The KKK thought Burke—one of the few black artists who had country-western hits—was white!

Burke performing in 1965

Burke performing in 1965As Burke later explained: “My drummer said to me, ‘Are we gonna get out of here alive?’ I told him, ‘Don’t quit playing till they say quit!’ We played ‘Down in the Valley’ for at least 45 minutes.”

From the late 60s onwards soul music was dominated by either the “psychedelic” or the more hard hitting social commentary of Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield, both of whom recorded albums that were statements of discontent and anger, reflecting an urgency to seek answers to problems in the here and now rather than the hereafter. While never truly political in nature, soul music’s ascent in the pop charts came to represent one of the first (and most visible) successes of the civil-rights movement.

Burke’s less directly political songs fell out of favour—though he was both a fan and a confidante of Martin Luther King—and these years were musically both commercially and artistically a poor time for him. Outside the music business, however, his life continued to flourish. His church grew to a congregation of about 5,000, he established a string of funeral parlours and continued with the production of what he called his “greatest achievement” his astounding family of 21 children (14 daughters, 7 sons), 90 grandchildren and 19 great grandchildren.

The mid-80s saw the musical wheel turn back in his favour, with his powerful and inspired live album Soul Alive! The rise continued with A Change is Gonna Come (1986)—described by critics as “one of the decade’s great soul statements.”

Burke, then in his mid-40s began touring in earnest again and continued to do so and record through the 1990s, even finding time to make his movie debut as Daddy Mention in the crime drama The Big Easy. He also performed for Pope John Paul II at the Vatican in 2000, which gained him a subsequent invitation to the Vatican’s Christmas celebration from Pope Benedict XVI.

Burke was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2001. This was followed the year after by the acclaimed Don’t Give Up On Me, which won a Grammy for best contemporary blues album and featured songs from Elvis Costello, Bob Dylan, Tom Waits, Brian Wilson, Dan Penn and Van Morrison. The album was a heartfelt testimonial to Burke’s life and achievements.

At a time when many men are thinking of retirement and kicking back, Burke went forward, restless to take on new musical challenges. In 2004 he appeared in the blues documentary, Lightning in a Bottle, which included performances with Junkie XL and Italian rock blues icon Zucchero at the Royal Albert Hall. His country-soul album Nashville (2006) featured guest appearances by artists of the quality of Emmylou Harris, Dolly Parton and Buddy Miller.

As a preliminary to his European tour in 2008, Burke released Like A Fire featuring his brilliant interpretations of songs by Harper, Keb’ Mo’, Eric Clapton and Jesse Harris.

Typically into the moment of the performance, Burke eschewed set lists with his band, playing whatever the audience wanted to hear. “It’s like turning back the hands of time instantly,” he said on his web site. “We can be in the middle of singing something from my recent Like A Fire album, and they’ll call out “Stupidity” from 1957 and we’re back 50 years!”

Solomon Burke

Solomon BurkeDuring these years his huge appetite for life had seen his weight soar to 400 lbs (181 kilos) and he had to be pushed on stage in a gold throne decorated with flowers. While remaining seated for the duration he gave every bit as much energy as if he had been able to stand.

I saw him perform around this time at The Basement in Sydney and there was no doubt we were in the presence of a master of his trade. There was more than a touch of the old preacher’s nostrum of “Start low, go slow, get high, strike fire, retire,” with not a gesture or note out of place. Burke’s highly-skilled band concentrated on building on the feel and the groove. They could tamp it down to a smolder or let it flash like an oxy torch and all points in between. And all over this was Burke’s voice—strident, imploring, aching, and demanding nothing but we join him in testifying to the power of music to lift us up and out of everyday concerns. If soul music was what you were after, this was the real thing.

Always keen to the end to improve and broaden his craft, Burke joined famed R&B producer Willie Mitchell in 2009 at Mitchell’s Royal Studio in Memphis to work together on a new recording. Mitchell, who had also collaborated with the likes of Ike & Tina Turner, O.V. Wright and Ann Peebles, had discussed the project with Burke for 30 years before they got together. That album, Nothing’s Impossible, stands alongside Rick Rubin’s homage to Johnny Cash and Loretta’s Lynn’s last album by Jack White as a masterly recapitulation and reinterpretation of an individual artist’s entire oeuvre.

Ultimately Burke died as he lived—on tour. How to encapsulate such a gargantuan life? Here’s a man who sold 17 million records, able to cut across genres, lauded by everyone who is anyone in contemporary popular music and credited with the invention of a new musical form and yet who claimed: “I’m a church minister first, then an entertainer.”

Well, forgive us if we disagree. And to be truthful, I suspect that Burke himself didn’t believe it. While his spiritual activity no doubt infused his musical and personal life, it was his ability to communicate on life as it is lived that drew audiences to him. He had the rare ability to contact an audience and allow them to feel something out of the ordinary world and to be uplifted by the power of music.

I think this desire to have people changed by his music is shown in arguably his greatest song—“None of us are free,” which is probably fitting to end this obituary with.

If you just look around you,

your gonna see what I say.

Cause the world is getting smaller each passing day.

Now it’s time to start making changes,

and it’s time for us all to realise,

that the truth is shining real bright right before our eyes

None of us are free

None of us are free

None of us are free, one of us are chained

None of us are free.