Dr. Richard Cooper

Dr. Richard CooperGrand Junction, Colorado, has emerged as the “poster child” for family practice. It was catapulted into this role when some folk were rummaging through the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care and found that it has the 23rd lowest Medicare expenditures per enrollee. Why not Dubuque, Iowa, which is the 3rd lowest? Like Grand Junction, Dubuque has very few disadvantaged minorities and very little poverty. But it lacks something that Grand Junction has. The majority of primary care physicians in Grand Junction are family physicians, while the majority in Dubuque are internists and pediatricians.

And so begins the tale. It led to the Atul Gawande piece in the New Yorker [The cost conundrum, June 1, 2009], which President Barack Obama so admired, and that led the president to Grand Junction, which he admired even more. Speaking there as health care reform was being debated in Congress, Obama said,

“Hello, Grand Junction! It’s great to be back in Southwest Colorado. Here in Grand Junction, you know that lowering costs is possible if you put in place smarter incentives; if you think about how to treat people, not just illnesses; if you look at problems facing not just one hospital or physician, but the many system-wide problems that are shared. That’s what the medical community in this city did; now you are getting better results while wasting less money.”

The tale ends, at least for now, in a paper in the New England Journal of Medicine last month, in which Tom Bodenheimer and David West proclaimed Grand Junction’s family practice-dominated health care as the model for the nation, concluding with a reminder best summed up as “pay us more.”

The sad part of this tale is that there is a very important reason that some areas of the nation spend less on health care than others, and they have nothing to do with primary care or any care. They have to do with poverty. Folks who are poor are generally sicker, and while the Dartmouth Doubletalk machine would have you believe otherwise, patients who are sicker and poorer use more medical care. So the real message from Grand Junction is that if your community is white and middle class, health care costs will be low, but if many of your neighbors are poor and disadvantaged, be prepared to pay more.

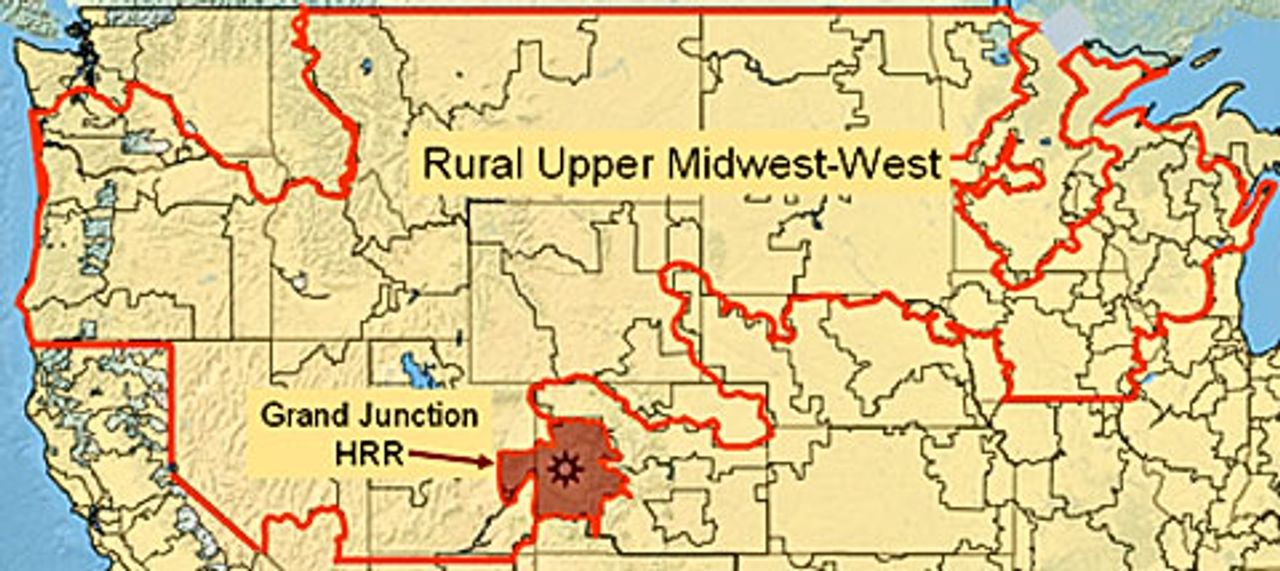

Geography and Demography: Grand Junction is the gateway to a broad swath of America that I call the Rural Upper Midwest-West (RUMW), which extends from Washington and Oregon to the western shore of Lake Michigan, skirting around urban areas that lie at its periphery, such as Seattle, Denver, Omaha, Minneapolis and Milwaukee. It covers 30 percent of the land mass of the US but has only 7 percent of the Medicare enrollees and 6 percent of the total population. It also has very few ethnic minorities: 0.5 percent are African-American, compared with 14 percent elsewhere, and 10 percent are Latino, compared with 18 percent elsewhere. And while poverty exists in the RUMW, it exists at a much lower rate and not in poverty ghettos.

Utilization and outcomes in the RUMW. On average, Medicare patients in the RUMW use 25-30 percent fewer services. On a per capita basis, hospital bed capacity and nursing supply are similar to elsewhere in the nation, but there are 4 percent fewer physicians, more of whom are primary care physicians, especially family physicians. When gauged against health outcomes, this appears to be more circumstantial than causative. As assessed by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, the RUMW has a more favorable panel of “health factors” (socioeconomic, behavioral, environmental and health system-related) and better measures of “health outcomes” (morbidity and mortality), and these two metrics correlate strongly with each other.

Health care in the Grand Junction HRR. The RUMW includes 43 of the 306 Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs) that make up the Dartmouth Atlas, as shown in the accompanying map. The Grand Junction HRR (population = 238,000) includes all or part of 10 counties, one of which is Mesa County (population = 146,000), which includes the city of Grand Junction (population = 58,000). The various descriptions of Grand Junction freely draw on these various units of analysis.

The Grand Junction HRR is very similar to the rest of the RUMW. By Dartmouth’s measure, it is near the middle, with lower spending in 17 and higher in 25. Grand Junction’s Medicare spending in is 98.5 percent of the RUMW average.

Most HRRs with lower spending are also within the RUMW. Indeed, only five are beyond its borders—Honolulu, Binghamton, New York, Lynchburg and Newport News, Virginia, and Albany, Georgia, but Albany is among these only because it fails to provide needed care; its mortality rate is 25 percent higher that average. Even those HRRs with slightly higher spending than Grand Junction’s are mostly in the RUMW. This includes 10 of the 19 HRRs where spending is no more than 5 percent higher. Clearly, there is something special about the RUMW, and one need only look at the demographics to figure out what that is.

Primary care. Much of the focus on the RUMW has to do with primary care. Overall, it isn’t much different than in the rest of the country. On a per capita basis, it has 4 percent fewer physicians and 4 percent more primary care physicians. But there is one big difference. More than 50 percent of the primary care physicians in the RUMW are family physicians, whereas, on average, there are fewer than 40 percent elsewhere in the US.

This is Family Practice Land. It’s where family practice succeeded in establishing training programs in the 1970s, while hospitals in the Northeast fended it off. It’s how Barbara Starfield was able to find an association between lower mortality and more “primary care,” but only family practice, not internal medicine or pediatrics. And it’s what led the Family Practice Academy to tout Grand Junction, where 60 percent of primary care physicians are family physicians. Although some parts of the RUMW have even more, like Appleton, Wisconsin, with 65 percent and both Sioux Falls, South Dakota and Casper, Wyoming, with 70 percent, Grand Junction became the poster child for family practice.

Grand Junction. So what do we know about Grand Junction? We know that it is family practice-dominated, that its demographics favor low health care spending, and that Medicare spending is low. In these ways, it resembles the rest of the RUMW. But there are several differences.

One is that, unlike the norm throughout the RUMW, Grand Junction does not have fewer physicians; it has more—18 percent more primary care physicians and 18 percent more specialists.

Second, Grand Junction has fewer long hospital stays and more hospice care, three times as much as elsewhere in the RUMW, although total utilization for out-of-hospital care, including skilled nursing and home care, is actually 10 percent greater than in the rest of the RUMW.

And finally, Grand Junction is rapidly growing. For the past 20 years, it has grown about 4 percent per year (four times the national average), which makes it one of the nation’s most rapidly growing communities in the RUMW and the nation. It also has a disproportionate supply of retirement communities, about half of which are for “active” retirees, which contributes to the fact that 15 percent of its population is Medicare-eligible, compared to 10 percent in Colorado and 9 percent nationally.

Grand Junction’s risks and outcomes. Mesa County’s mortality rate is 72 percent of the national average. Its health status is superior to other counties in the US in 15 of 19 measures, and it is similarly superior to a group of 26 counties that the US Department of Health and Human Services has identified as Mesa County’s “peers,” based on population, age distribution, poverty and frontier status.

According to the University of Wisconsin’s county ranking system, the “health factors” and “health outcomes” rankings in Mesa County are equivalent, indicating that outcomes reflect risk, and similar equivalency between rankings exists for all of the Grand Junction HRR. And while Medicare expenditures in the counties that comprise the Grand Junction HRR are in the lowest two quintiles when unadjusted, they are in the third and fourth quintiles when adjusted for various risk factors by researchers at Texas A&M.

Taken together, these findings indicate that Grand Junction’s better outcomes reflect its better health status, and its costs, although lower because risk is lower, are somewhat higher than would be expected for the demographic and health status risks that it has. In all, it is rather average.

This conclusion stands in stark contrast to the conclusion in the September 2010 issue of Health Affairs that Grand Junction has “a superior health system.” In support, Marsha Thorson and her colleagues in Grand Junction presented their comparison of mortality and readmission after hospitalization for heart failure, pneumonia or myocardial infarction at Grand Junction’s only hospital and 20 comparison hospitals. They found that Medicare patients in Grand Junction had fewer hospitalizations, shorter hospitalizations and lower mortality rates than patients in the comparison hospitals.

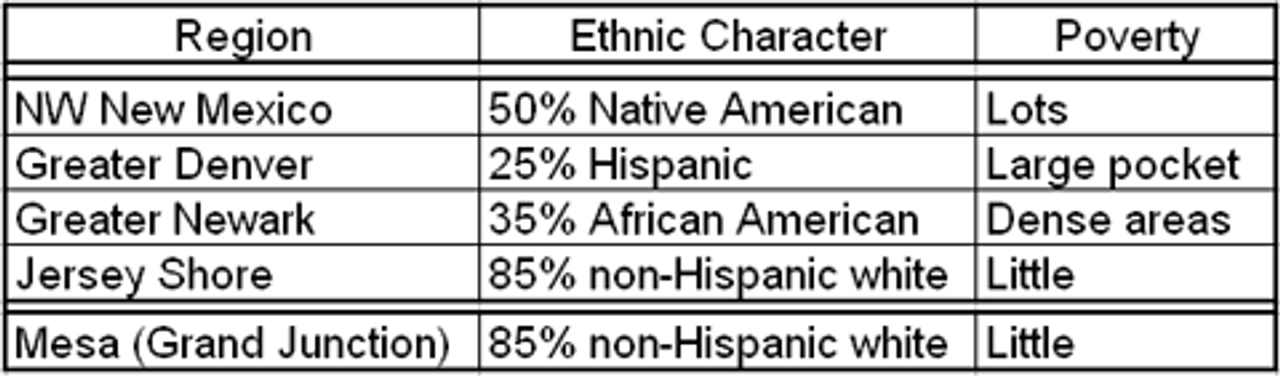

The accompanying graphics were rather convincing. But one important detail was omitted. What were the comparison hospitals? It was odd that such information was not provided. But the paper did note that these hospitals were in Colorado, New Mexico and New Jersey, and with some much appreciated help from the authors, I was able to determine that these 20 comparison hospitals were located in four clusters of 10 counties. Some of the details, along with those for Mesa County, are in the accompanying table.

Two hospitals were in northwest New Mexico, where 50 percent of the population is Native American and the poverty rate is higher than 20 percent. A second group was in the Denver region, with its large Latino population. The third was in the Newark area, with its large African-American population and dense poverty. And the fourth was in two wealthy counties along the New Jersey shore.

When all 20 of these comparison hospitals were averaged, the good outcomes among affluent patients on the Jersey Shore were overwhelmed by the poor outcomes among ethnic minorities in Newark, Denver and northwest New Mexico, which made Mesa (Grand Junction) look exceptional. As they say, figures don’t lie….

There may be merit to the way physicians practice in Grand Junction, but there is no evidence that they achieve superior outcomes or lower costs than the rest of the RUMW. Nor are their outcomes better than expected on the basis of health factors. But there’s one thing I have not touched upon. The folks in Grand Junction are satisfied. They are proud of their system. And for good reason. Grand Junction has the luxury of an abundant supply of physicians. Indeed, to make that same supply available everywhere in the US would require 80,000 additional physicians. And that’s using Grand Junction, a low-risk community, as the standard. To bring all communities to Grand Junction’s level on a risk-adjusted basis would take twice that number, or more.

So I’m happy that Grand Junction is happy. I just wish they would stop misrepresenting what goes on there and allow the rest of the nation to confront its terrible problems of too much poverty and too few resources.

See: http://buzcooper.com/2010/11/06/the-grand-deception/