This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: 23,000 die after Colombian government ignores volcano warnings

Nevado del Ruiz volcano in 1985

Nevado del Ruiz volcano in 1985On November 13, 1985, the volcano Nevado del Ruiz in Tolima, Columbia, erupted, triggering massive landslides that engulfed the city of Armero and nearby villages, killing an estimated 23,000.

The human toll of the tragedy was entirely preventable. Teams of scientists monitoring the volcano had repeatedly warned the Colombian government that an eruption was likely in the preceding months and even the final days before the disaster. The most complete forecast came on October 22, three weeks before the disaster, from a team of Italian volcanologists, who warned that an explosion was imminent and supplied the government with a series of simple steps to protect and save the population.

Nothing was done to prepare Armero, which was an important agricultural city precisely because of the rich volcanic soils of its hinterland.

At a mass funeral soon after the explosion in nearby Ibague, one mourner aptly declared, “The volcano didn’t kill 22,000 people. The government killed them.”

Yet seven days earlier the full force of the state had been mobilized to crush the occupation of Colombia’s Palace of Justice by “M-19” guerilla rebels. The army was quickly mobilized, and in the ensuing battle over 100 were killed, among them 11 Supreme Court justices.

No such mobilization was mounted for the people of Armero after the earthquake. This was highlighted to a world audience by the tragic fate of a 13-year-old girl, Omayra Sanchez, whose legs had been trapped under rubble and sludge after she had attempted to rescue a sibling. For three days she remained in this position, close enough to be photographed by the media, before finally succumbing to gangrene and hypothermia.

French photographer Frank Fournier described the scene. “All around, hundreds of people were trapped. Rescuers were having difficulty reaching them. I could hear people screaming for help and then silence—an eerie silence,” he told the BBC. “It was very haunting. There were a few helicopters, some that had been loaned by an oil company, trying to rescue people. Then there was this little girl and people were powerless to help her.”

50 years ago: Kennedy beats Nixon in 1960 elections

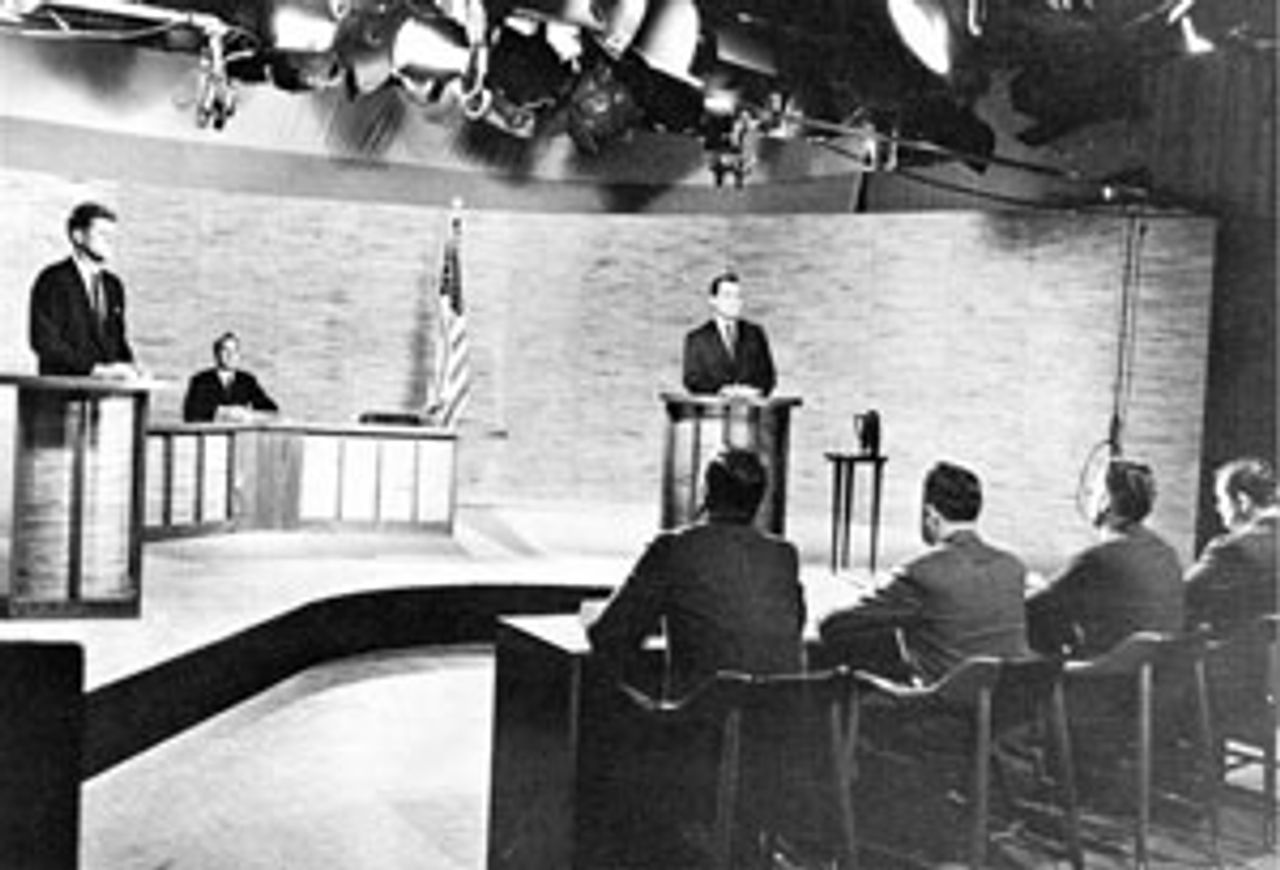

Televised debate between Kennedy and Nixon

Televised debate between Kennedy and NixonIn the 1960 US elections, held November 8, Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy beat Republican Vice President Richard Nixon in one of the closest-ever presidential elections. Only one tenth of one percentage point separated the two in the popular vote, while in the decisive electoral count Kennedy won by securing more of the heavily populated states—including Illinois, where it was alleged that Chicago’s machine mayor Richard Daley had secured the razor-thin margin necessary to deliver the state to the Democratic column.

The 1960 election was the first to include two candidates born in the 20th century, and it was the first to feature televised debates. Kennedy’s victory brought with it the first presidency of a Roman Catholic, a fact the senator downplayed.

Kennedy ran on a platform that included a call for an expansion of social spending, including the establishment of an old age public health insurance system. He also gave indications that he might favor advancing civil rights for blacks in the segregated South. Nixon ran on a platform calling for the continuation of the policies of the Eisenhower administration during the 1950s, years of extraordinary economic growth. Neither candidate advocated cutting social spending.

In foreign policy there was little to distinguish the two, with both touting an expansion of US militarism around the world. Kennedy, in particular, had emphasized the loss of US “prestige” under Eisenhower—singling out the Cuban revolution of 1959 as an example—and advocated a dramatic increase in military spending.

75 years ago: John L. Lewis founds the CIO

John L. Lewis of the United Mine

John L. Lewis of the United MineWorkers

On November 9, 1935, the Committee for Industrial Organizations was founded by John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers of America and the leaders of seven other unions who opposed the American Federation of Labor’s refusal to organize industrial workers. Lewis became the CIO’s first president and maintained that position until 1940.

The CIO was founded just one month after the American Federation of Labor’s annual convention held in Atlantic City, New Jersey. There, the AFL rejected the call for industrial unionism, the organization of all workers in a given industry under one union, in favor of craft unionism, in which workers are organized according to specific trades within an industry. The AFL also rejected the formation of a labor party and voted to prevent members suspected of being communists from assuming leadership positions within the organization.

The CIO was initially formed as an opposition movement within the AFL, releasing a statement upon its founding saying it would continue to fight for industrial unionism within the federation. “It is the purpose of the committee,” the statement read, “to encourage and promote organization of the workers in the mass production and unorganized industries of the nation and affiliation with the American Federation of Labor. Its functions will be educational and advisory and the committee and its representatives will cooperate for the recognition and acceptance of modern collective bargaining in such industries.”

The members of the CIO were expelled from the AFL within a year, after which they would rename themselves the Congress of Industrial Organizations. As an independent organization, the CIO experienced an explosive growth in membership. By 1937, it had organized roughly 4 million workers under its banner.

100 years ago: France loses battle in Chad

A Senegalese tirailleurs of

A Senegalese tirailleurs ofthe French army

On November 8, 1910, a force of some 600 French officers and their Senegalese tirailleurs suffered a defeat in the Battle of Doroté in eastern Chad at the hands of an estimated 5,000 African soldiers of the sultanate of Quaddai, who were armed with rifles. After the battle, the Quaddai forces retreated to British-held Sudan.

Forty-four of the French force were killed and 74 were wounded. An unknown but likely far higher number of Chadian fighters were killed. Among the French dead was the leader of the expedition, Lt. Col. Moll. It was the second serious defeat suffered by France in Chad that year—on January 4 a force of 109 was ambushed and massacred on the frontier at Massalit, with only a handful of survivors spared to report the disasters.

France had sought to annex the Quaddai sultanate, also called Wadai, beginning in 1904. The effort proved more costly than anticipated. Only in 1909 was Paris able to raise the tricolor over the palace of Sultan Dudmurah in Abeche, capital of Quaddai. But Dudmurah reorganized and solicited aid from the Sultanate of Darfur to the west, setting the stage for the war of 1909-1911

Paris aimed to establish a dominant position in the northern part of the continent, to be called French Equatorial Africa, a part of the larger “scramble for Africa” among the European powers. Quaddai had gained wealth and power in the region due to its strategic position astride a trans-Saharan trading route to Benghazi in Libya, then part of the Ottoman Empire. With Britain firmly entrenched along the more strategically important Nile River valley from Uganda to Egypt, and controlling South Africa, France was most concerned with Italy’s imminent invasion of Libya.