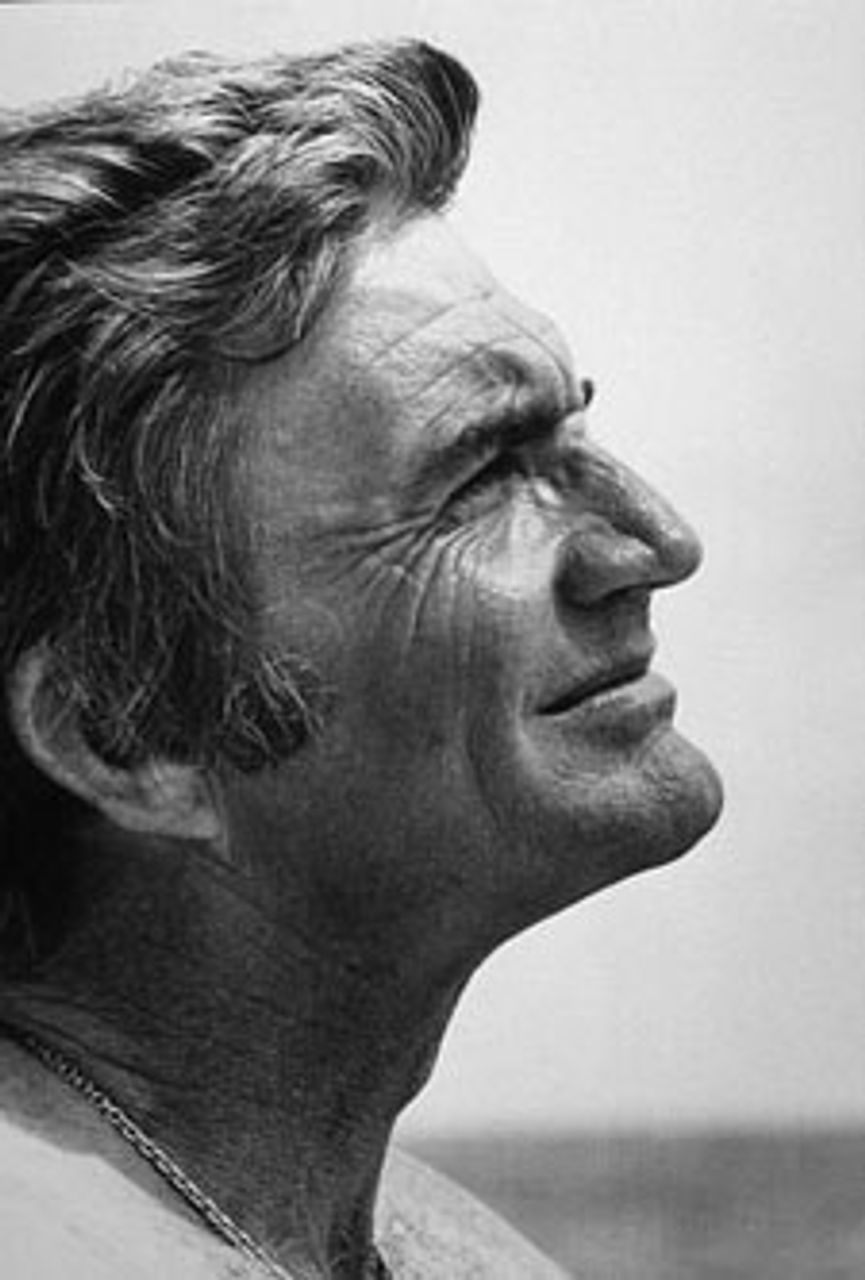

Blake Edwards

Blake EdwardsBlake Edwards, the talented director of many classic Hollywood films including Breakfast at Tiffany’s and the Pink Panther series, died December 15 at Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, California. He was 88. Edwards was among the more talented, lively and genuinely entertaining filmmakers to emerge in the American cinema during late 1950s and early 1960s. Following his death, Edwards’s wife of 41 years, actress and singer Julie Andrews, released a statement saying, “He was the most unique man I have ever known and he was my mate. He will be missed beyond words, and will forever be in my heart.”

The future director was born William Blake Crump in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1922. When Edward’s biological father left the family before his son was born, his mother remarried and the family moved to Los Angeles. Edwards was practically raised in the film industry; his grandfather had been a director of silent films, and his stepfather worked as a producer. In high school, the young Edwards took a job as a courier on the big studio lots.

By the 1940s, Edwards had begun his own film career. He found work as an actor, performing in several small supporting roles. A stint in the US Coast Guard during the Second World War interrupted his career, but he would soon return as a writer of radio productions and film. He struck up a partnership with director Richard Quine (Strangers When We Meet, My Sister Eileen), for whom Edwards would write several scripts.

Edwards directed his first feature film, Bring Your Smile Along, in 1955, but it was as creator, writer and director of the television series Peter Gunn (1958-1961) that he first gained popular recognition.

The series, about a private detective, stands out among other shows of its time for its sophistication and its sense of cool. If one can use the phrase, a “jazz sensibility” is evident not only in the memorable score by frequent Edwards collaborator Henry Mancini, but in the content of the show itself. The series notably featured blacklisted actor Herschel Bernardi in a leading role, two years before the blacklist was “officially” broken with Spartacus in 1960.

The social and artistic climate in which Edwards developed as an artist and made his first films was very different from that of the previous decades. The postwar boom period brought an improvement in living conditions for a section of the population and opened up new opportunities. The Great Depression and the war years had finally ended, and for the first time in a great while, many working class families had gained some breathing room, so to speak. Good paying jobs and a certain level of economic security could be found.

These changes in the economic situation brought with them new social moods and, with those, new artistic sensibilities. One can see expressed in the 1960s films of Edwards some of the confidence and optimism that many now felt. There is a breeziness and even a mischievousness in his work.

In Hollywood, the blacklist was finally lifted along with certain written and unwritten moral codes of censorship. Filmmakers no longer had to be so cautious in what they said and could get away with a little more. In Edwards’s excellent comedies Operation Petticoat (1959) and What Did You Do In The War, Daddy? (1966), for example, one sees an attitude toward the US military, its commanding officers in particular, and a treatment of the Second World War, that would not have been possible in the preceding years.

But while the social changes then underway allowed filmmakers new freedoms, they still faced very real challenges. The blacklist and the purge of left-wing figures and sentiments from Hollywood and other spheres of cultural life in the US had taken an enormous toll. Artists developing in the wake of this assault were cut off from anything resembling a socialist culture of the kind that had enriched filmmakers of a previous generation.

To a great extent, the up-and-coming filmmakers of the 1960s were left unarmed when it came time to deal with the contradictions of postwar society. While there were several significant films made by Edwards and contemporaries such as Robert Mulligan and Arthur Penn, the 1960s marked a general decline in Hollywood filmmaking.

Blake Edwards’s films were energetic, ambitious and more than willing to cross lines of taste and convention. But even in many of his best works one sees an unevenness, a difficulty in creating sustained, cohesive works. Many of the dramas tend to be more memorable for scenes and sequences rather than as complete, fully worked-out pieces. The comedies are often built around a rapid-fire succession of gags, some of which hit their mark and some of which do not. One tends to remember the best moments, however, and there are certainly a large number of them.

Breakfast at Tiffany's

Breakfast at Tiffany'sMany recent tributes to Edwards have praised Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) and Days of Wine and Roses (1962) as among the director’s finest. They are certainly two of his more better-known films. Both works have their strong moments: the party sequence at the apartment of Holly Golightly (Audrey Hepburn) in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, for example, in which Edwards’s sharp comic touch is particularly evident.

In Days of Wine and Roses, one remembers the riverside conversation between Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick in which Lemmon’s character expresses his guilt over the questionable duties he is required to perform as a public relations agent for wealthy corporate clients. The performances of the relatively young actors in both films are appealing. Both dramas are somewhat overwrought in places, however, and neither film is entirely successful.

With the Pink Panther series, in which the bumbling police inspector Jacques Clouseau is tasked with thwarting jewel thieves or solving murder mysteries, Edwards hit his comedic stride and formed a long-lasting, if contentious, partnership with the remarkable comic actor Peter Sellers.

The funniest moments in The Pink Panther (1964) are those in which Clouseau’s good intentions go horribly wrong. The well-meaning inspector, portrayed by Sellers, can be seen inadvertently slamming his wife’s head into a bar as he tries to help her recover from a coughing fit, or dragging her off a bed onto the floor while trying to kiss the foot he has just stepped on by accident.

A Shot in the Dark

A Shot in the DarkIn A Shot In The Dark (also 1964), the laughs come as Clouseau’s confidence continually crashes up against the reality of his incompetence. During the course of a murder investigation, Clouseau manages to set himself on fire, fall out of a window, and is himself arrested on a number of occasions. Riding a wave of blind momentum throughout the Pink Panther series, Clouseau’s good intentions wreak havoc on everyone and everything around him. A Shot in the Dark, the second of the Clouseau films, remains the best in the series.

In The Party (1968), Edwards reunited with Sellers for another comedy in which Sellers portrayed an accident-prone Indian actor whose clumsiness has just destroyed a major Hollywood production. The actor is then mistakenly invited to the Hollywood party of a studio executive where he now threatens to destroy both the party and the executive’s expensive home with his talent for getting into trouble. The film was made from a script of no more than 50-60 pages, and Sellers is given plenty of room to improvise.

While The Party is a very funny film, there’s something rather dark going on underneath it all. One remembers the bullying of a sensitive young actress by one studio chief, and the utter disdain for the “foreigner” who has somehow arrived in the midst of these complacent, well-to-do individuals. Each time Sellers opens a door in the executive’s house, something suspicious is going on behind it that the partygoers would rather have remained hidden. Edwards and Sellers take great delight in sending all of this crashing down on itself.

What Did You Do In The War, Daddy?

What Did You Do In The War, Daddy?Along with A Shot in The Dark and The Party, Edwards’s most satisfying comedy of the 1960s was What Did You Do In The War, Daddy? Set during the Second World War, the film tells the story of a group of US soldiers who are ordered to invade an Italian village. Once inside the town, they find the Italian soldiers do not wish to fight and will voluntarily surrender on the condition that they be allowed to go through with a festival that had been planned for that evening. The US and Italian soldiers decide to celebrate together and spend the night drinking heavily and enjoying themselves to the full. The next day, when their superiors demand news of the invasion, the soldiers are forced to fake a battle for the benefit of the surveillance planes flying overhead.

While Edwards made many of his best films in the 1960s, two of his more significant works came much later. In 1979, Edwards directed 10, starring Dudley Moore and Julie Andrews. Moore plays a wealthy but unhappy composer who has a midlife crisis and becomes obsessed with a young woman he considers to be the “perfect 10.” When the voyeuristic musician finally has the chance to be with her, he discovers fantasy and reality are two very different things.

In 1981, Edwards directed S.O.B., a devastating comedy about Hollywood. A film director whose latest movie was a flop, losing millions for his studio, has lost his mind as a result. After several failed suicide attempts, he is suddenly inspired to transform his film into a semi-pornographic work in hopes of making it a box office success. He proceeds to transform the most innocent of musical numbers into an absurd, sexual fantasy. The story takes place in the midst of Hollywood parties and significant levels of excess and corruption. It is difficult to think of another Edwards comedy that is so severe. There is considerable anger and disgust that comes across in the work. One gets the sense that Edwards knows this world intimately, and detests it.

Edwards continued directing into the early 1990s. There were strong moments in many of his later works including That’s Life (1986), which reunited the director with Jack Lemmon, and Victor/Victoria (1982), another of Edward’s best-known films, although the latter work has been considerably overrated.

In 2004, Edwards received an honorary Academy Award. Ever the devotee to slapstick, the director appeared at the awards ceremony in a wheelchair, which suddenly ran out of control across the stage before crashing through a wall. Edwards then walked to the microphone, covered in dust, to accept his award.

Even as his health declined in recent years, Edwards continued to work. At the time of his death, he was preparing two new musicals for the Broadway stage, one based on the Pink Panther films and the other an original comedy set during the Prohibition era of the 1920s.