This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: “Baby Doc” Duvalier flees Haiti

Haiti

HaitiOn February 7, 1986, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, fled Haiti, bringing to an end three decades of US-backed dictatorship that had begun under his father, Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier.

With the backing of the US, the Duvaliers were responsible, acting through their hated Tonton Macoutes secret police, for the murder of more than 50,000 Haitians, and the imprisonment, torture, or banishment of hundreds of thousands more. The brutal repression was used to keep Haitian workers in abject poverty to the benefit of US corporate interests and the Duvaliers and the Haitian elite, who looted the government and the economy to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

The desperation of the population and its hatred for the regime led to revolt in 1985. Beginning in Gonaives, it spread across the country through the autumn and into January. Duvalier attempted to stop the uprising through police terror on the one side, and a 10 percent cut to basic food commodities on the other. These efforts failed, at which point the Reagan administration determined that Duvalier had to go.

A number of countries refused to receive Duvalier. He was ultimately whisked away on a US Air Force flight to Haiti’s former colonial master, France, where he lived in luxury in a villa on the Riviera.

50 years ago: Layoffs at GM Australia provoke crisis

Australia's Liberal Party PM

Australia's Liberal Party PMRobert Menzies

The February 10, 1961 announcement by General Motors-Holden’s, the GM subsidiary in Australia, that it would layoff 2,500 workers in response to austerity measures by the Robert Menzies’ Liberal Party government provoked a political crisis.

In spite of the relatively small size of the layoff compared to Australia’s overall workforce of some 4 million, the dismissals were a source of grave concern in a nation in which virtual full employment had become the post-war norm. It also pointed to the subordination of the Australian economy to global pressures.

The Menzies government had sharply tightened credit at the end of 1960, and singled out the auto industry by slapping a 10 percent sales tax on car sales. The aim was to slow inflation and reduce a growing balance of payments deficit based in large part on imports related to auto production—rubber, steel, and gasoline. As a result, auto sales plummeted by about half from 1960 to 1961.

In response to the crisis, the Menzies government announced that it had negotiated the sale of US $61 million worth of grain to China, the largest direct Australian grain sale since World War I, averting the need for “reimposing import restrictions or devaluing the currency,” according to one contemporary account. The move led to calls in the Sydney Daily Mirror and the Melbourne Age for diplomatic recognition of Beijing.

75 years ago: French Socialist Party leader Blum severely beaten by fascists

Leon Blum

Leon BlumOn February 13, 1936, Socialist Party leader Leon Blum was publicly beaten by fascist thugs while attending the funeral for the far-right French monarchist historian and journalist Jacques Bainville, who had died four days earlier. Spotted by members of the paramilitary group Camelots du Roi, Blum was dragged from his car and severely beaten. Six months later Blum would head the disastrous Popular Front government, which, with the support of the Communist Party, suppressed the revolutionary strivings of the French working class.

The savage attack on Blum demonstrated the advanced social polarization in France and the growing assertiveness of fascist elements such as the 500,000-member Croix-de-Feu and the Camelots du Roi, which was affiliated to the royalist and anti-Semitic movement Action Francaise, co-founded by Bainville. It also lent credence to the political line advanced by Leon Trotsky—and rejected by the French Stalinists and Socialists—that French workers had to build popular militias based on the trade unions to combat the fascist threat.

Bainville first came to national prominence during the Alfred Dreyfus affair in the mid-1890s, as a proponent of the persecution of Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer falsely accused of treason. In spite of its marked similarities to the National Socialists in Germany, the French far-right agitated for an alliance with Mussolini’s fascist Italy and Great Britain against Nazi Germany. According to Bainville, German weakness was essential for France to prosper. Bainville’s work was utilised by the German fascist movement as proof of French hatred for their country.

100 years ago: British, Canadian, and US tensions over North American free trade deal

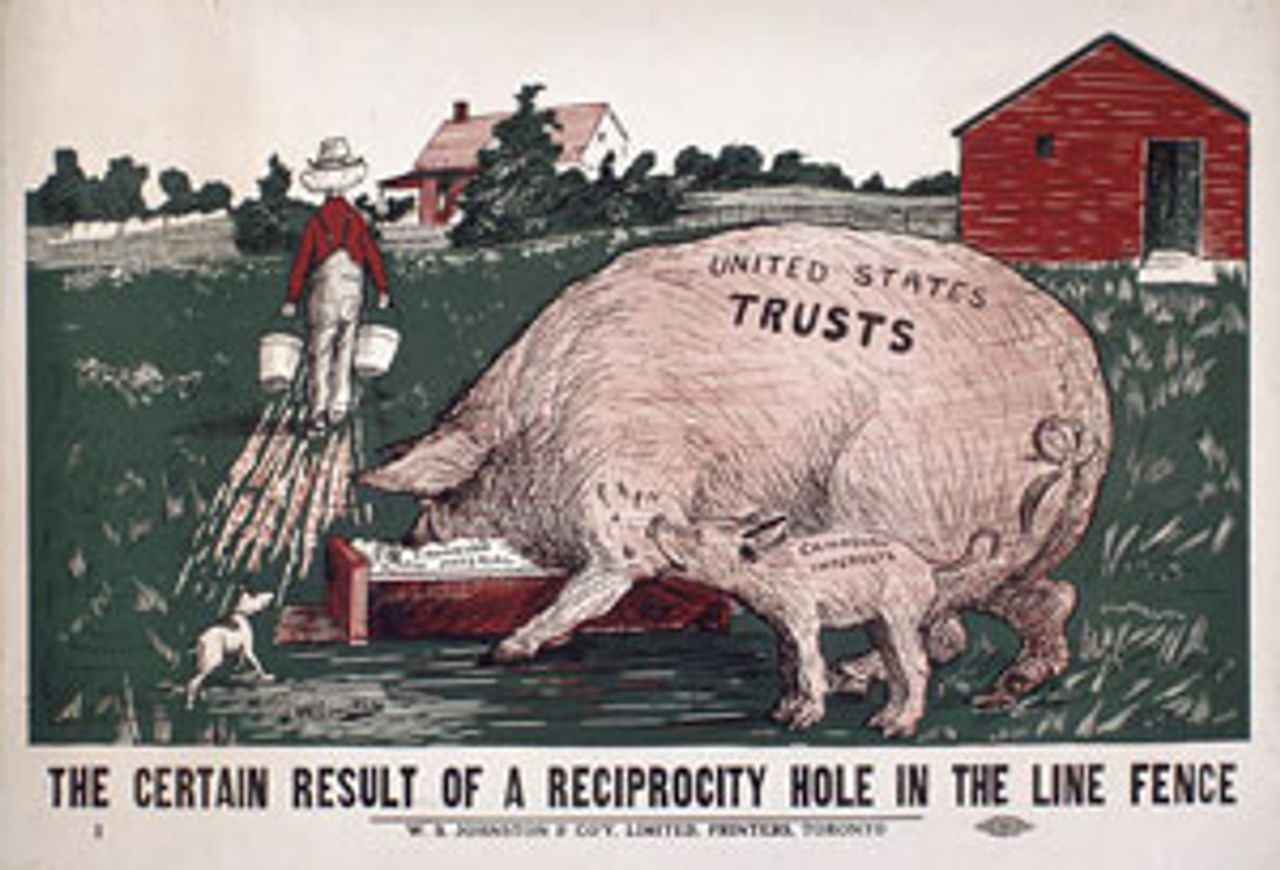

Canadian cartoon attacking free trade deal

Canadian cartoon attacking free trade dealThe attempt in 1911 by the William Howard Taft administration in the US and the Liberal government of Wilfred Laurier in Canada to put through a free trade or “reciprocity” agreement cutting tariffs provoked sharp disagreement in ruling circles in the US and Canada, as well as Great Britain, which still retained the power to pass laws concerning its dominion, Canada.

In the US the agreement was heavily backed by Republican president Taft and most congressmen from the Northeastern industrial states, who looked to gain access to Canadian raw materials and agricultural products. Politicians representing industries in the US potentially threatened by the deal—grain producers, fish production, and pulp lumber producer—opposed the bill.

A challenge in Britain’s House of Commons led by Austen Chamberlain focused on whether or not Laurier had consulted British authorities on the decision, and the implications for British capitalism were Canada’s economy to be entirely reoriented to the US. Chamberlain, a Liberal Unionist, demanded the imposition of “an imperial tariff” to protect British domination of its colonial possessions and dominions. The same week, a nearly hysterical article in Britain’s Saturday Review, entitled “The American Challenge,” warned that the agreement might reduce the United Kingdom to the status of a second-rate power. “The British Empire has withstood many shocks,” the newspaper states, listing Napoleon and the rise of Germany, “but now the challenge ... comes from our most formidable of all our rivals, the United States of America.”

In Canada, the opposition attacked the plans as the product of “continentalism” and the destruction of the dominion’s British heritage. Robert Borden, a leader of the Conservative opposition, spoke for three hours in parliament, warning that the trade deal would undo a quarter century of Canadian efforts to build up east-west trade, rather than just north-south. “We must decide whether the spirit of Canadianism or that of continentalism shall prevail on the northern half of this continent,” Borden declared.