This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: South Africa attacks neighbors

Citing as justification the Reagan administration’s bombing of Libya a month earlier, on May 19, 1986 the Apartheid regime in South Africa launched unprovoked attacks on the capital cities of its neighbors—Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The South African government of President P.W. Botha claimed that the raids were justified by the activities in the three countries of militants of the African National Congress (ANC), which Pretoria dubbed a “terrorist” organization.

Three people were killed, two of them in a refugee camp near the Zambian capital of Lusaka. None of the dead were members of the ANC.

Aircraft attacked targets in Lusaka, and helicopters and commandos raided the capitals of Botswana and Zimbabwe (Gaborone and Harare, respectively), destroying ANC buildings in the latter. In June 1985, 12 people had been killed in another unprovoked South African attack on Botswana.

The raids appeared to be aimed at scuttling semi-official negotiations between a body called the Eminent Persons Group and the ANC. The talks had taken place in Lusaka days before the attack.

At a deeper level, the bombing reflected the desperation of the Apartheid regime in the midst of a massive uprising of South Africa’s urban and tribal masses that had begun in 1984. In the space of a year-and-a-half, over 1,500 blacks were killed, most at the hands of security forces, and tens of thousands more had been imprisoned and tortured. Yet in spite of the repression, the revolutionary upsurge continued to gain strength, rattling financial markets’ confidence in the Botha regime and driving down the value of the currency, the rand.

The Reagan administration expressed “outrage” over the attacks. This was entirely hypocritical. The US itself listed the ANC as a terrorist organization, while Washington’s attack on Libya, and its ally Israel’s recent attack on Tunisia, were expressly cited by Botha as a rationale. “We will fight terrorism in precisely the same way as other Western countries,” he declared after the raids.

50 years ago: Military coup in South Korea

Park Chung-hee (front right) commanding his coup troops

Park Chung-hee (front right) commanding his coup troops A May 16 coup d’état led by Major General Park Chung-hee brought to an end the Second Republic in South Korea only one year after the collapse of the dictatorial regime of Syngman Rhee.

Chung-hee and his junta, the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction, sought a military-police solution to the crises besetting South Korea, which included a low level of industrialization, a trade deficit, a weak currency, 2 million unemployed workers, and a growing assertiveness by the working class and the youth.

The Second Republic, which came to power on the basis of mass protests over the abuses of the Rhee regime, had not resolved any of the social demands of the population. It had strengthened the hand of the military and US imperialism by stoking tensions with North Korea seven years after the armistice that halted the Korean War.

Chung-hee would rule South Korea until his assassination in 1979. His regime was based on two principles: breakneck industrialization and anti-communism. The latter was a catch-all for suppressing working class opposition in order to enrich a layer of South Korean capitalists closely tied to the government.

Among his first acts was to arrest 930 citizens on “suspicion” of communism. Within one month he would create the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), which would assume a controlling role not only in espionage, but in the development of the export-oriented economy.

The coup was tacitly welcomed by the US, which feared that social unrest among workers and youth could result in the establishment of an unfriendly government in the strategically crucial nation. The New York Times in a May 19 editorial called on Washington to work with the regime in “every way possible,” and hailed the junta as “able, patriotic men, who want to maintain friendly relations with the United States and strengthen South Korea’s capacity to resist Communist aggression.”

75 years ago: Trotsky warns of Stalinist extermination of socialists

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky In an article entitled “Stalin Plans Wholesale Persecution,” published May 16, 1936 in the New Militant newspaper, Leon Trotsky warned that Stalin intended to exterminate thousands of socialists in the Soviet Union. Referring to the March 15th edition of Pravda, Trotsky drew attention to a semi-official order within the newspaper’s pages that could only have come with Stalin’s backing.

Entitled “On Bolshevik Vigilance,” the Pravda article indicated the persecution awaiting expelled party members. In response, Trotsky explained how Stalin delineated between the simply recalcitrant and those deemed Trotskyists. “With unexampled bureaucratic Jesuitism, Stalin intervenes in behalf of certain categories of the expelled,” he wrote. “Ruthlessness is recommended only with regard to the political opponent. A docile grafter is not an enemy. The mortal enemy is the honest Oppositionist, who must be deprived of work of every kind.”

Trotsky had been informed of the enormous anti-Trotskyist terror occurring within the Soviet Union by three of his followers, who for various reasons had evaded the clutches of the Stalinist bureaucracy: A. Tarov, a Russian worker and old Bolshevik; Anton Cilinga a former member of the Yugoslavian Communist Party Politbureau; and Victor Serge, a writer and former Left Oppositionist. These sources confirmed for Trotsky the existence of a network of concentration camps within the Soviet Union and the torture employed by the GPU secret police to extract false confessions. Trotsky’s son-in-law, Platon Volkov, had already been arrested earlier in the year. He would be executed in October together with others accused of Trotskyism.

Trotsky ended the article with an urgent call to action. What was happening to his followers in the Soviet Union “must be brought to the attention of the workers the world over,” Trotsky warned. “Not a single appropriate occasion should be missed to raise this question at workers’ meetings… Everything must be done to prevent Stalin from physically exterminating tens of thousands of irreproachable young fighters.”

100 years ago: Treaty of Ciudad Juarez ends first phase of Mexican Revolution

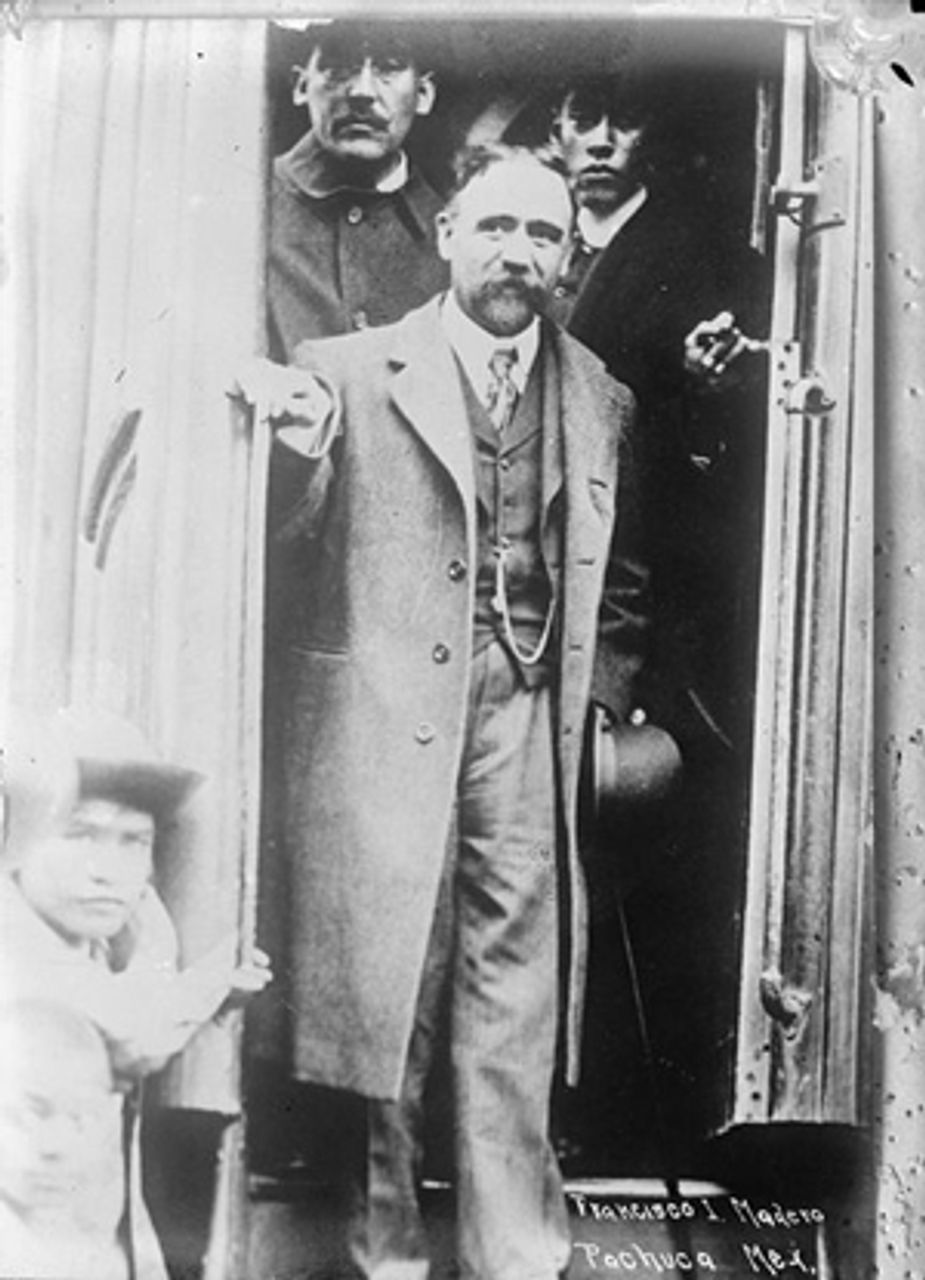

Madero in 1911

Madero in 1911On May 21, 1911, the leader of the revolutionary forces in Mexico, Francisco Madero, signed a pact with President Porfirio Diaz ending fighting and bringing to an end the first phase of the Mexican Revolution.

The agreement reflected Madero’s narrow conception of the revolution. It left untouched the Porfirian state, did nothing to satisfy the social grievances of the impoverished masses, and neglected almost all of the democratic demands Madero had spelled out in his “Plan of San Luis Potosi.”

The deal hinged largely on Diaz’s decision to resign. Along with Diaz, Vice President Ramon Corral was to resign, and leading diplomat Francisco Leon de la Barra would be interim president. The pact also called for the disbandment of revolutionary forces, leaving the federal army as the only militarized force in the nation.

Madero, in fact, opposed any reforms that would threaten the power of the Mexican elite, including the large landholders, of which his own family was a member. This explains the curious fact that as the revolution gained strength and the government’s position crumbled, Madero sought with greater urgency to work out a deal with Diaz.

In the North, Madero had held back an attack on the federal garrison in Ciudad Jaurez, while he offered new concessions to Diaz—up to and including dropping the demand for Diaz’s resignation. This was scuttled only by the insubordination of Madero’s two generals, Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa, whose attack on the city easily routed Diaz’s forces on May 10.

Of greater concern to both Madero and Diaz were developments in the South, where the question of redistribution of the hacienda land had emerged and Emiliano Zapata and his peasant supporters achieved resounding military success during the first three weeks of May. It was Zapata’s capture of Cuatla on May 19 that persuaded Diaz to accept Madero’s terms.